In the 1970s Venezuela was widely admired for its functional democracy and the highest living standards in Latin America. There was good reasons to be optimistic.

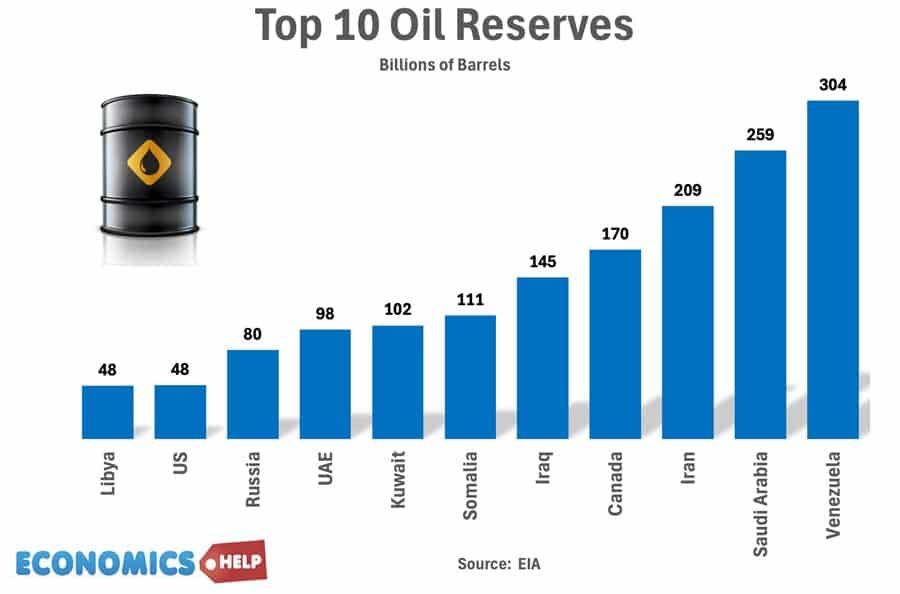

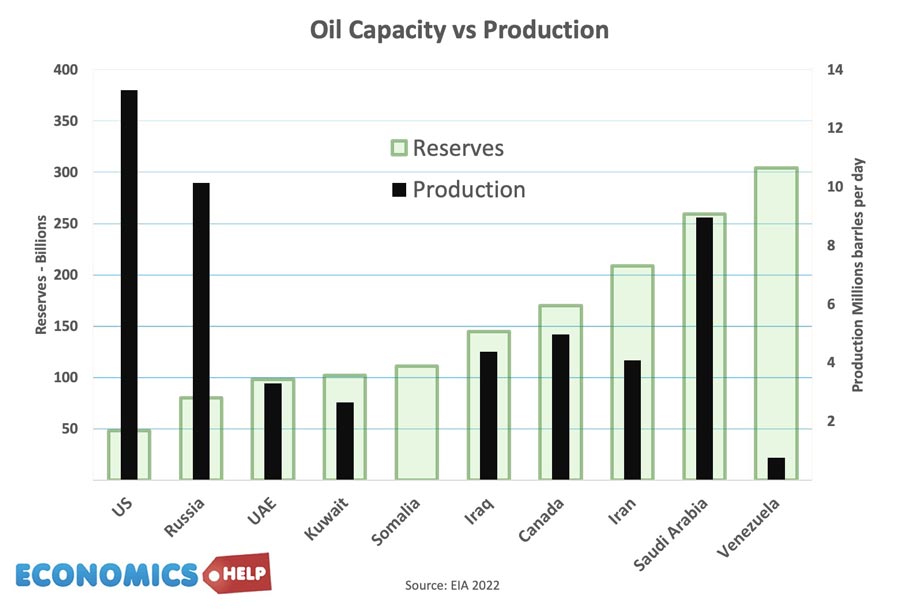

Venezuela has the largest known reserves of oil in the world. Greater than Saudi Arabia, Iran and the US.

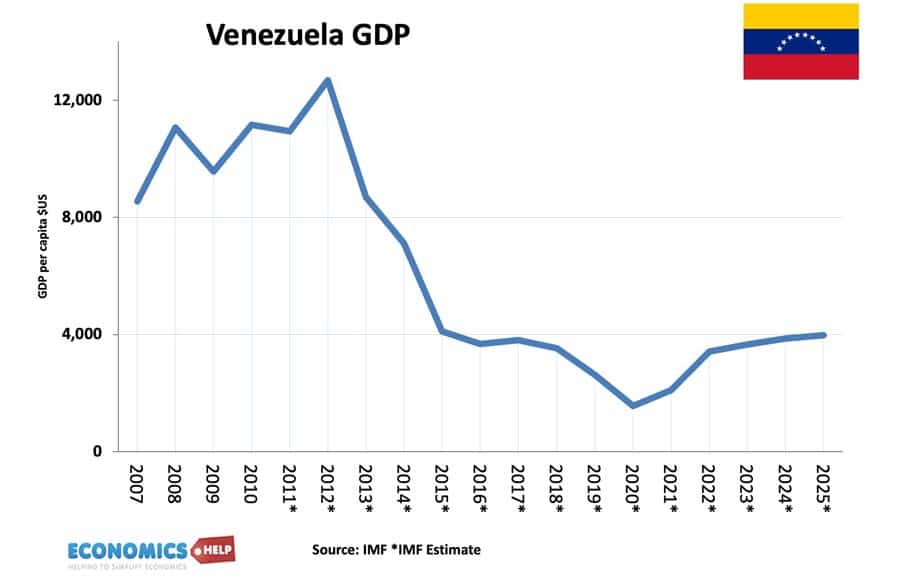

Yet in recent decades, the economy has lurched from crisis to disaster recording an unprecedented fall in GDP of 65%. How did a country with so much potential end up with hyperinflation, empty shelves and millions of people fleeing the country?

Origin of Oil

In 1922, the first major oil field saw oil literally spurt from the ground at a record breaking 100,000 barrels of oil a day – Venezuela was soon the 2nd largest producer in the world. Like the Gulf states, in Venezuela, oil literally sits below the surface, giving it one of the cheapest production costs. But whilst UAE and Saudi Arabia have got rich from oil – building skyscrapers in the desert, Venezuela is bankrupt, seemingly drowned by its own riches.

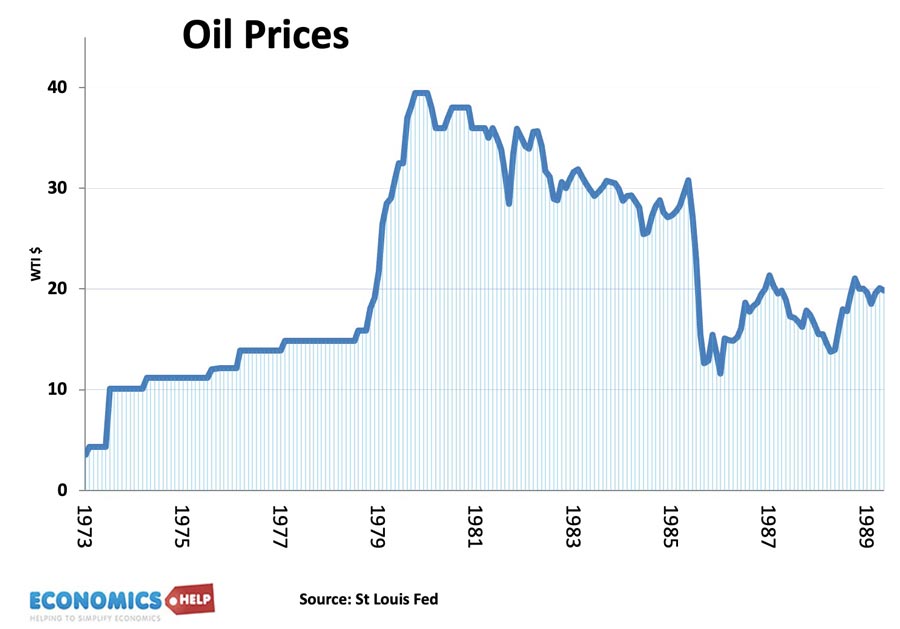

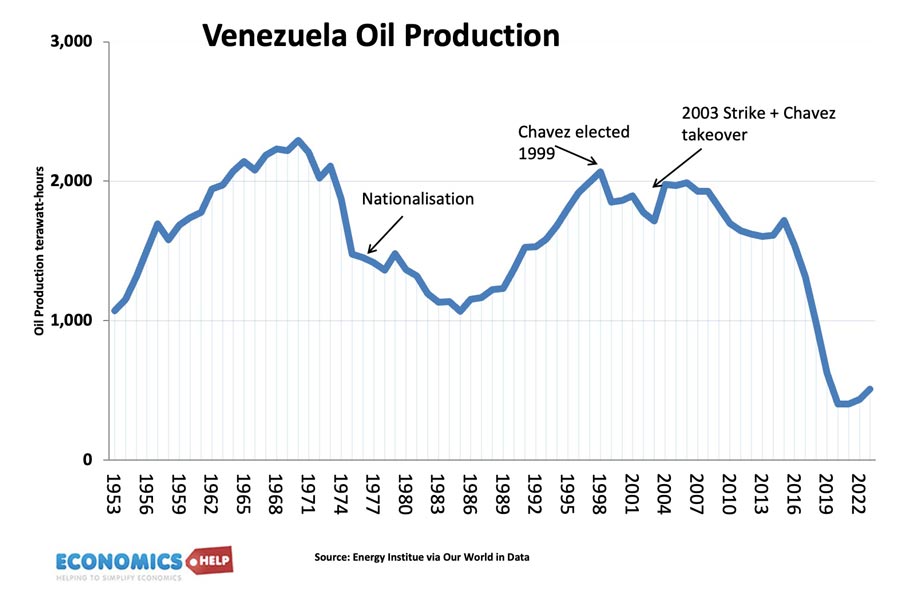

For decades Venezuela was a deeply unequal country, and initially, the oil fields were owned by foreign multinationals who did nothing to uplift the country or reduce poverty. But, by the 1970s, the oil industry was effectively nationalised, creating a state-owned monopoly. And initially, the soaring oil price of the 1970s, gave the economy and government revenue a real bonanza. GDP soared, and tax revenues increased.

Resource Curse

But, this is the first problem with huge reserves of oil, it can distort the economy. When oil production increases so does the currency. As oil revenue soars, other exports, like Venezuelan coffee become uncompetitive and so the oil industry soaks up more investment and focus. You get an economy dominated by oil. Oil accounts for 80% of Venezuela’s exports and 70% of government revenue.

The problem is that whatever goes up, can also come down. In the 1980s, oil prices slumped and everything went into reverse GDP fell, and government tax revenues declined. In fact tax revenues fell so disastrously, the government sought loans from the IMF. The IMF insisted on the usual Washington Consensus of austerity and balancing the books. And against this backdrop, Hugo Chavez, a former military officer, rose to prominence. He promised an end to corruption, austerity and inequality, and in 1999, Chavez came to power on the back of a populist wave.

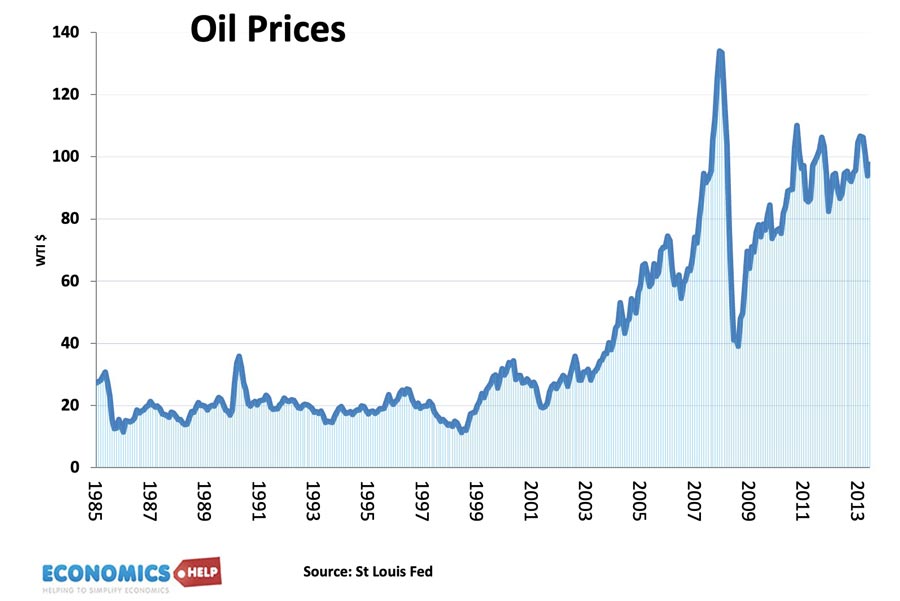

Helped by a rise in oil prices Chavez embarked on a surge of government spending, distributing oil profits to his mostly poor supporters. For a short time inequality fell, health care improved and Chavez’s popularity soared. But, behind this extravagant spending, there was a growing cloud over the economy.

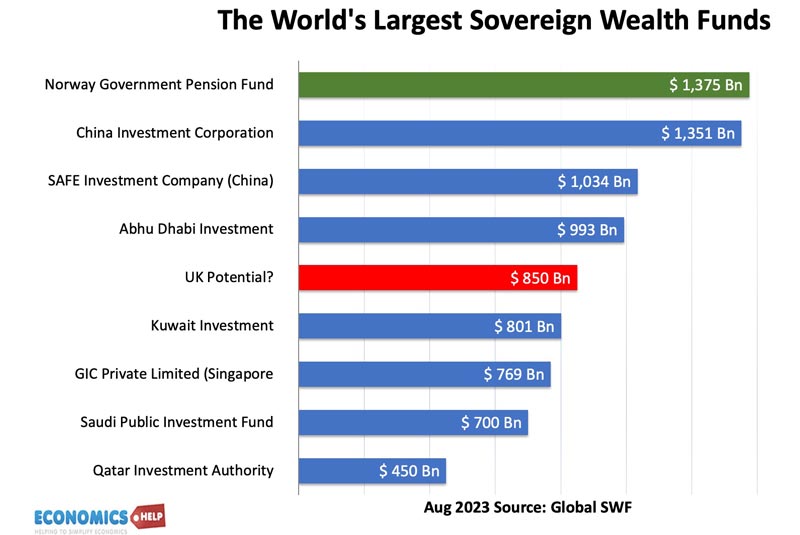

When countries like Norway and Qatar became oil-rich, they set up a Sovereign Wealth Fund. This involves investing profits in overseas investments not connected to oil. This does three things, it lowers the value of the currency, helping other exporting sectors. It diversifies the economy away from reliance on oil and provides sustainable long-term income whatever might happen to oil prices. Venezuela did nothing. Its non-oil economy was negligible, nearly every consumer good was imported. In fact, in the inflation crisis, it struggled to pay the foreign company printing its back notes. In fact, Venezuela even struggled to produce oil.

When Chavez was elected president in 1999, Venezuela was producing 3.55 million barrels a day, in 2023, it produced just 0.85 million. How can a country whose whole economy relies on oil, fail to produce the stuff when it is literally sitting just below the ground?

Problems of Oil

Firstly, the nationalised oil company PDVSA was used as a piggy bank to fund social programmes, money was diverted from any investment. Rather than just focus on oil, it was tasked with building housing and buying food imports. Also after the strikes of 2002 the company was run by political supporters rather those workers with expertise in the industry. And then there was the corruption. No one really know how much but at least $70 billion has been syphoned off in an industry with no accountability, but where political favours were everything. Whilst supermarkets were empty, people report oil bosses having lunch delivered by helicopter. When the US imposed sanctions, Venezuela sold oil through crypto networks, but this just became an opportunity for more corruption. Venezuela ranks among the top four most corrupt countries in the world, along with South Sudan, Syria and Somalia.

Inflation

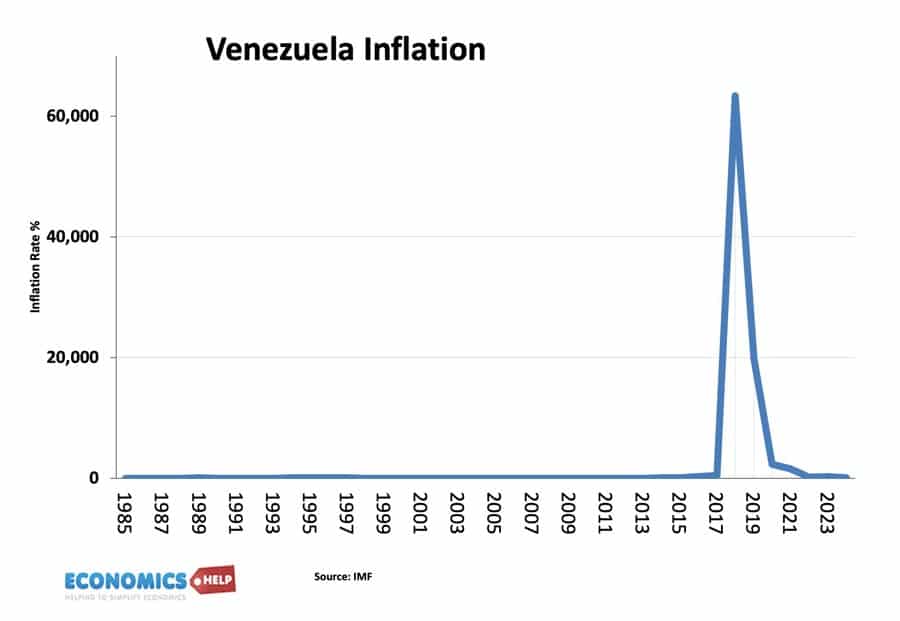

As the economic situation darkened, the government responded by funding more social programmes to retain popularity. It is worth mentioning the social welfare programmes were not focused on investment, education or building new infrastructure, but mostly just cash payments. Yet, when oil prices collapsed in the mid 2010s, the government couldn’t keep up with its debt repayments and spending commitments. The response was to print money. What could possibly go wrong? The result was predictably a surge in inflation. Money lost value and the currency went into meltdown. By 2018, inflation was 63,000%. In 2019, the currency lost 90% of its value in 4 months. In 2019, there were 8 Bolivars to one dollar by Sep 2021 it was 4 million. However, this episode shows how one bad economic policy can easily lead to more bad policies.

Price Controls

With prices soaring, consumers couldn’t afford goods. The solution was to control prices and control the exchange rate. The government set up its own supermarkets where prices were controlled and kept affordable. The problem is no supplier could afford to sell at these fantasy prices. Supermarkets were frequently empty. There was a huge incentive to buy from government supermarkets and resell elsewhere or over the border. The solution was to only allow people to buy one one day of the week, install high tech finger scans in the empty supermarket to prove consumer identity and bring in the army to maintain order. Shopping became a nightmare, households could spend several hours to queue up for food in severe short supply. In 2017, the crisis was so severe 75% of Venezuelans reported losing weight an average of 11kg. This is not a developed world-style crisis where prices rise 10% and wages stagnate. People were literally going hungry.

Sanctions

If this wasn’t bad enough in 2017, in response to growing authoritarianism, US imposed crippling sanctions which limited access to financial markets. Unemployment soared, GDP fell. No wonder nearly 8 million Venezuelans have left the country in recent decades. In 2017 41% stated they would like to leave permanently. And the tragedy is that it was often the most highly skilled workers who were the first to leave. Under Venezuela’s planned economy, there is no logic to how people get paid. Many doctors working in the state sector for very low wages left the profession as they could earn more money in the informal sector, being a taxi driver or street vendors.

Exchange Controls

As the exchange rate plummeted, the government tried to maintain a fixed exchange rate, which again was divorced from the market reality. To fix the exchange rate, the government imposed capital controls, if you want to get dollars to buy imports, you need to apply to the government. Permission can take months and was subject to the usual personal favours and political allegiance. The result was a huge divergence between the official exchange rate and black market rate. Companies who gained the right to buy imports, had an incentive to sell part of the dollars on the black market. No wonder there are so many empty shelves. Venezuela lacked foreign currency and the exchange controls distorted the economy.

Venezuela is undoutedly one of the worst examples of the resource curse. Oil has distorted the economy and created an economy with no accountability or flexibility. It is also an example, of how when things start to go wrong, it is easy to choose policies which gave very short-term respite but only store up more problems. Printing money enables payments for the next month, but causs inflation. Price controls, give a theoretical respite, but lead to chronic shortages. The currency collapses, but exchange controls can’t alter the outcome.

Related

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DEXVZUS