Greece is the cradle of western civilisation. Philosophy, democracy and unique cultural icons. But, 15 years ago, something terrible started to happen to the Greek economy, which saw one of the biggests hits to living standards in the western world. GDP collapsed, unemployment soared and Greece became an economic basket case. This article explains what went wrong and what lessons we can learn.

It wasn’t always like this. After joining the EU in 1981, just seven years after the end of the military dictatorship, Greece became a success story, experiencing rapid economic growth and inflow of new investment, EU funds and growth in tourism. Yet, underneath this growth lurked problems, productivity was lower than in other European countries, the government had a chronic inability to collect taxes, especially from the self-employed and the government had a tendency to large fiscal deficits, and bouts of inflation. Yet, the dawn of the Euro single currency seemed to offer hope that Greece, could once and for all tame its problems of inflation and high deficits. The hope was to tie the Greek economy to the northern powerhouses and get the best of both worlds.

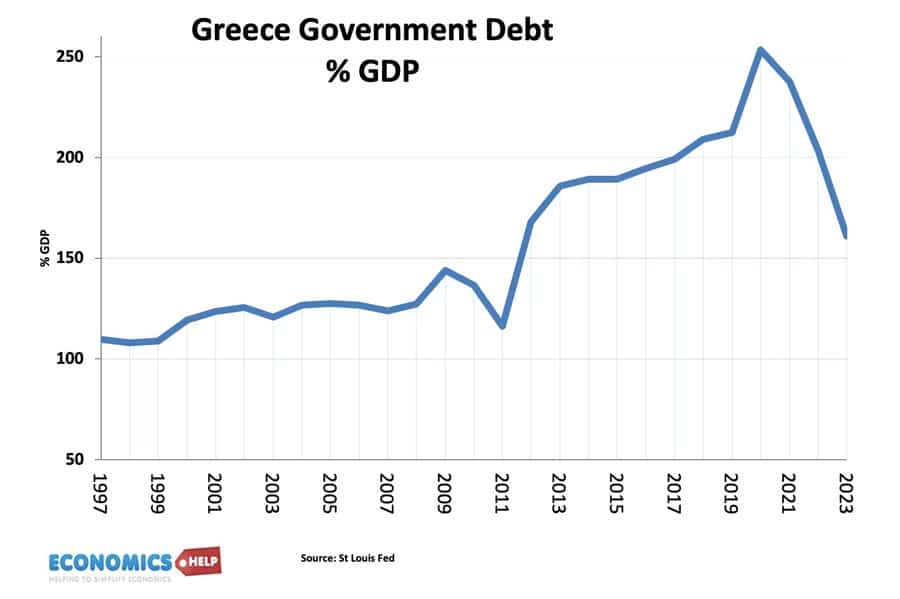

The problem was that to join the Euro, Greece had to meet fiscal targets set out by the Maastricht Treaty, debt less than 60% of GDP, deficits less than 3%. The truth is Greece was nowhere near, but with false accounting, and an EU happy to look the other way, Greece entered the Euro in 2001 despite being nowhere near fiscal targets.

Euro

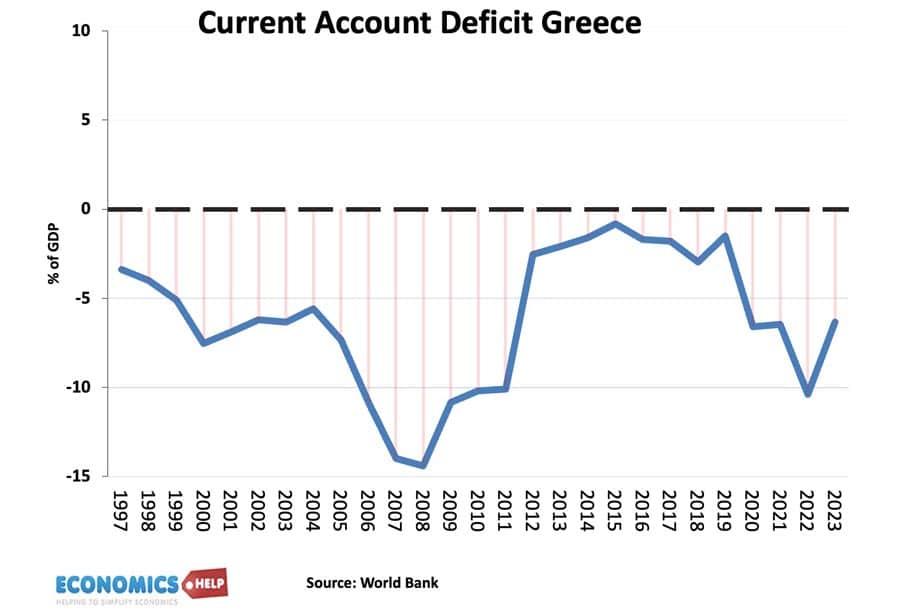

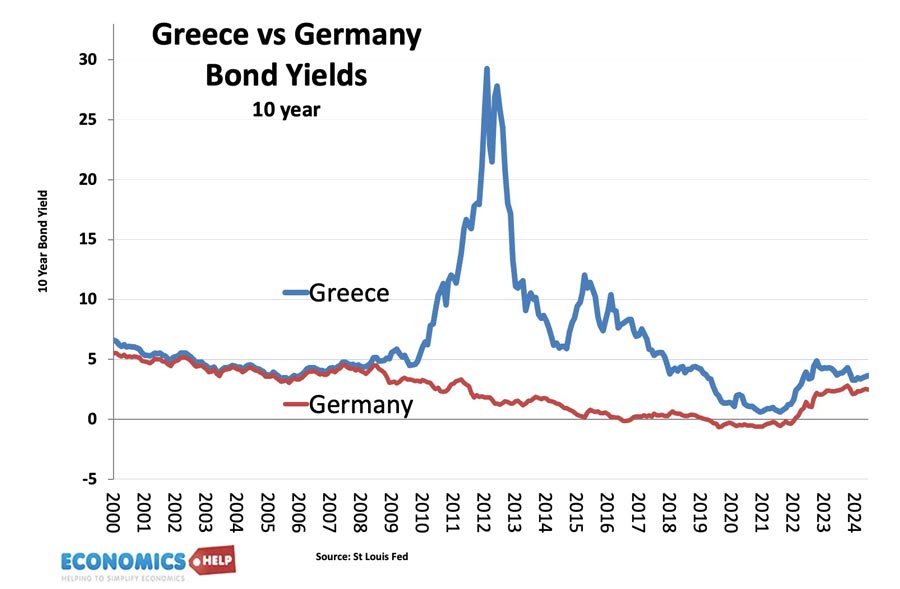

For seven years, the Euro seemed a blessing. Markets assumed Greek debt was now safe so bond yields were as low as Germany’s yields. The Greek economy took advantage and went on a borrowing binge. Buying luxury foreign imports such as German cars, at ultra-low interest rates. Yet, whilst consumption rose, so did problems of productivity, higher inflation and lower competitiveness.

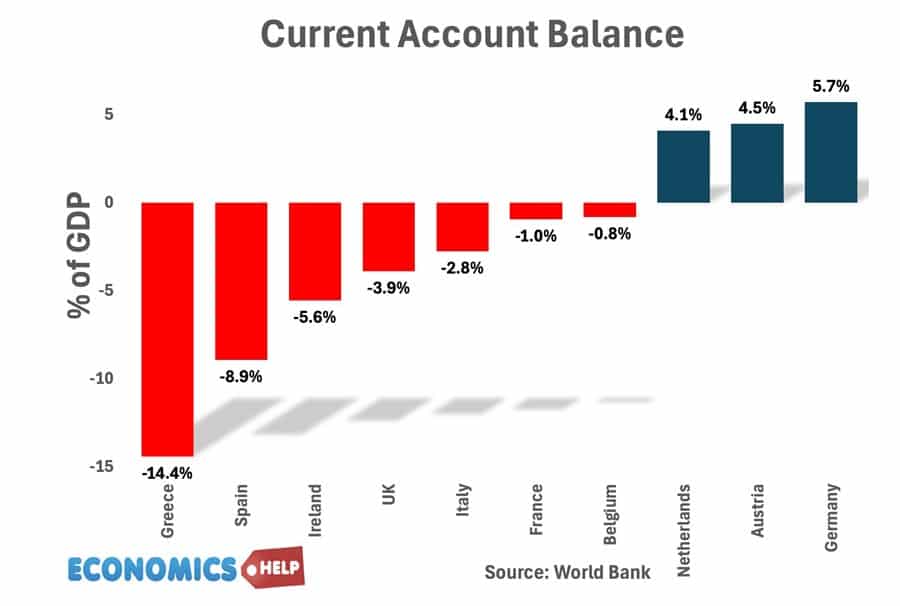

The Greek current account deficit started to soar, reaching 15% of GDP in 2008. It’s hard to emphasise just how unprecedented it is for a country to such a large trade imbalance. In the Euro, other countries like Spain experienced a similar problem, but Greece was off the scale. It was heightened only by record levels of Greek government debt.

But, then the global credit crisis hit and the party came to an end. Europe went into a recession, banks became short of finance and Greek loans started to be recalled. The problem is debts were so massive that the Greek economy struggled to finance them. The Greek finance sector was in meltdown. For years, markets assumed Greek debt would be as safe as Germany’s. But, in 2010 they they suddenly became labelled as Junk status. Bond yields soared from 2% to 30%. Not only had Greece massive debt, but now it had a surge in interest rate costs which overwhelmed the government.

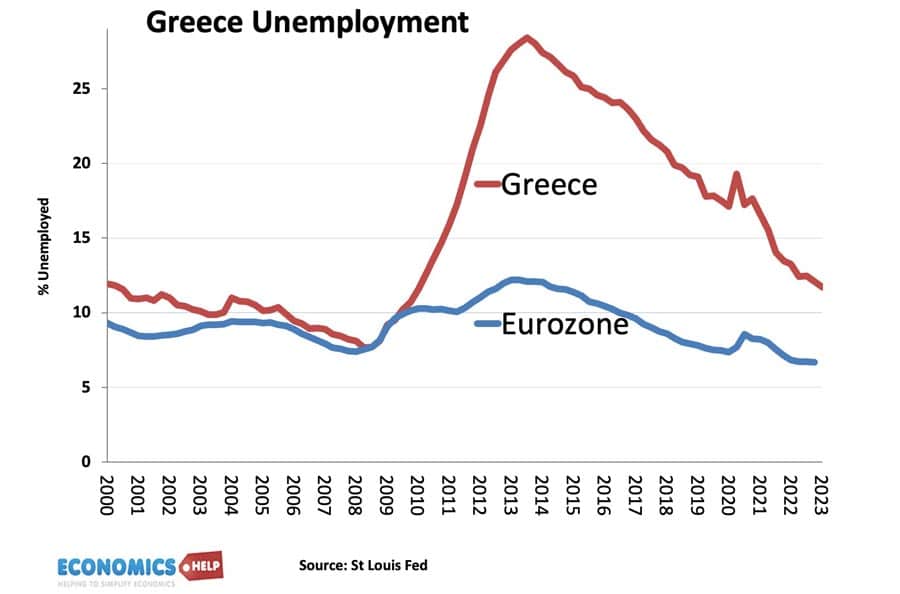

The Euro had been supposed to bring countries together, but facing their own crisis, German and northern taxpayers were in no mood to keep subsidising what they saw as profligate Greek spending. The EU imposed severe austerity on the Greek economy, spending was slashed and EU bailouts were only given to help Greece repay its creditors. But, this government austerity had a disastrous effect on the economy, wages fell, output declined and unemployment soared, and an estimated half a million Greeks fled the country. If Greece had not been in the Euro, the outcome would undoubtedly have been different. They could have devalued currency to restore competitiveness and a Central Bank could help deal with liquidity issues. But, the Euro is the ultimate Hotel California. You can join, but you can never check out. The only thing worse than the austerity of the Euro, was actually leaving the Euro and facing massive inflation and capital flight as Greeks would try to hold onto the value of their savings.

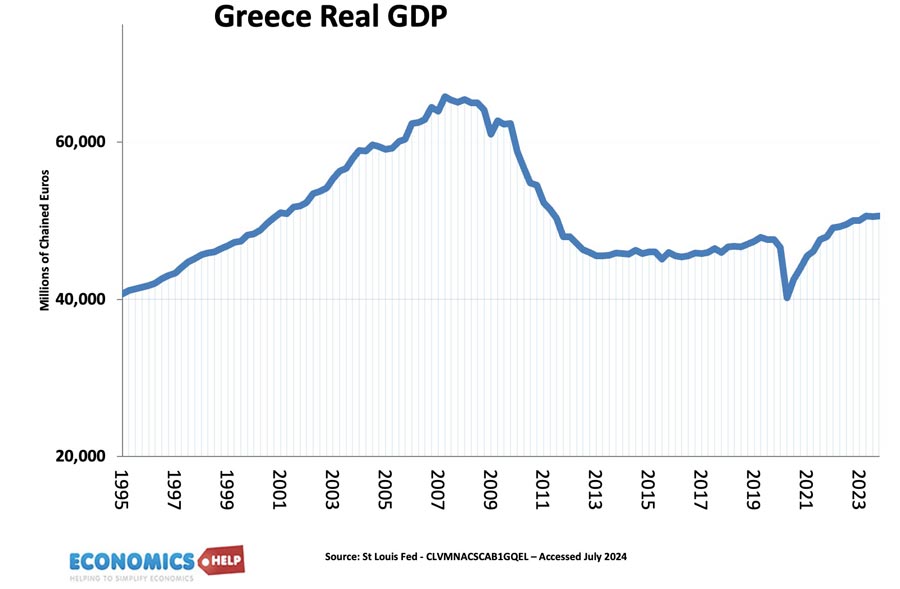

By 2015, the Greek economy was on its knees it had seen a decline in GDP twice as bad as the UK during the Great Depression of the 1930s. It seemed Greece had only bad choices. It defaulted on a loan repayment to the IMF becoming the first developed country to achieve this distinction. Yet, from this depth of 2015, the Greek economy has seen a steady if not remarkable recovery. How has Greece gone from the butt of jokes to one of fastest growing economies? But, first there are five lessons can Europe draw from the Greek crisis. Firstly, the single currency is no magic bullet. Unless there is a degree of economic convergerence, the Euro could be a disaster, especially for former Communist countries with significantly different structures and wage rates. Secondly, markets can be irresponsible in lending, credit rating agencies gave Greece high ratings when it had spent beyond its capacity. They only downgraded to junk status when it was too late. Thirdly, restoring competitiveness through austerity led to unacceptable inequality and high level of economic and personal misery. 25% unemployment and an economy in ruins were a giant failure.

No wonder the Greeks have the lowest approval of the EU on the continent. Fourthly, Greece made a huge mistake in allowing debt to increase during years of growth, not collecting taxes and wasteful government spending. Fifthly the problems of today store up problems for the future. The loss of growth and workers have exacerbated the ageing population and a country which has the most generous pension system in the world faces growing demands in the future. It already spends 16% of GDP on pensions alone. One of the highest in Europe.

Greece Recovery

That’s the bad news, but how do we account for Greece become one of the fastest growing economies in Europe? Well, firstly, it is something of a statistical illusion. If you lose 20% of weight because you go on an extreme fast, it is easier to put that weight back on. Despite the recovery, GDP is still below the pre-crisis peak. Secondly, the crisis did force much needed reforms, there has been a degree of better tax collection, deregulation and some privatisation which has unlocked efficiency from a very bureaucratic public sector. Interestingly whilst the UK and other countries talk about a 4 day week, Greece has talked about a 6-day week – whether it will be implemented is another matter, but there is a renewed determination to improve the Greek economy and work hard. Thirdly, the very painful economic decline, did reduce wages and restore competitiveness, leading to improved growth in areas like tourism and agricultural exports. Greece is even seeing IT startups materialise. Fourthly as the economy recovered from the depths of recession, unemployment fell causing improved consumer confidence and higher spending. This has led to postiive economic growth which has finally led to improved tax revenues and repayment of foreign loans. As repayments have progressed, Greece has seen lower bond yields, better credit ratings, and lower interest rate payments. When you get stuck in a negative spiral, economies can shrink on themselves, as Greece found out. But, the reverse is also true, when economies recover, it can unlock a positive cycle of improved confidence and investment.

This is not to say all is well with the Greek economy. Unemployment is still above the European average, the recent rail disaster showed a legacy of poor standards in public provision. Greeks work the longest hours in Europe, but have the lowest levels of productivity. Government spending on unproductive areas of the economy is still high. Greece also has the highest rate of military spending as a share of GDP in Europe. The economy is also still hampered by a very high share of tax revenue and GDP going on pensions. Greece has one of the most generous pension systems in Europe, but this combined with long-term ageing trends, means government spending is rising, crowding out much-needed public and private investment. Greece’s recovery is very welcome after tumultuous decade, but what are the effects of Europe’s ageing population on future economic prospects, this video looks into more detail.