What can the UK Learn from the Greek Economy?

Which country was one of the fastest-growing European economy in the past three years? Yes, you’ve correctly guessed, it was Greece. To the north, the once mighty German economy is struggling to avoid recession, to the east, Turkey is facing inflation of 70%, and the UK’s GDP per capita is still lower than 2019. IMF forecasts for 2024, suggest Greece will far outperform the Eurozone on the back of a surge in investment and EU recovery funds. What lessons, if any can the UK take from the Greece economy?

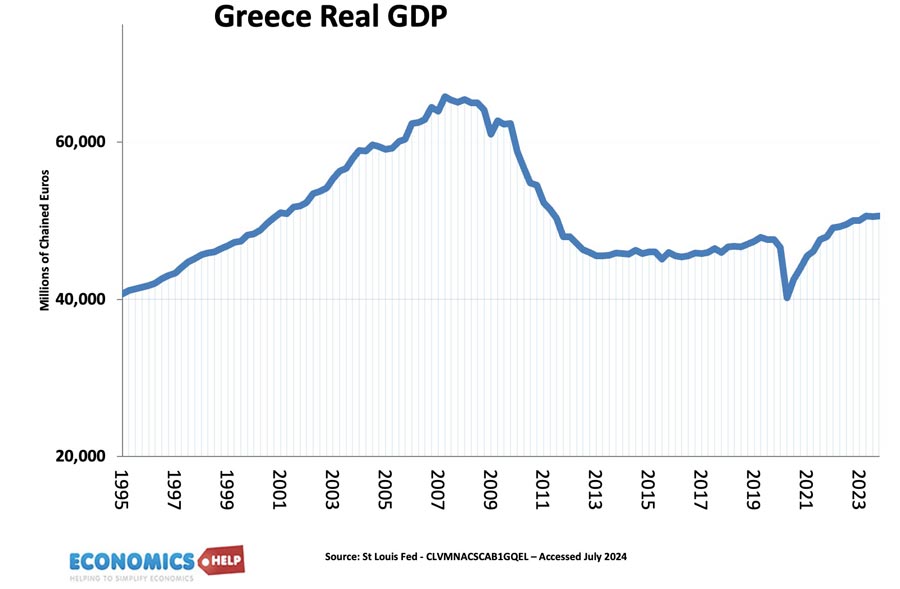

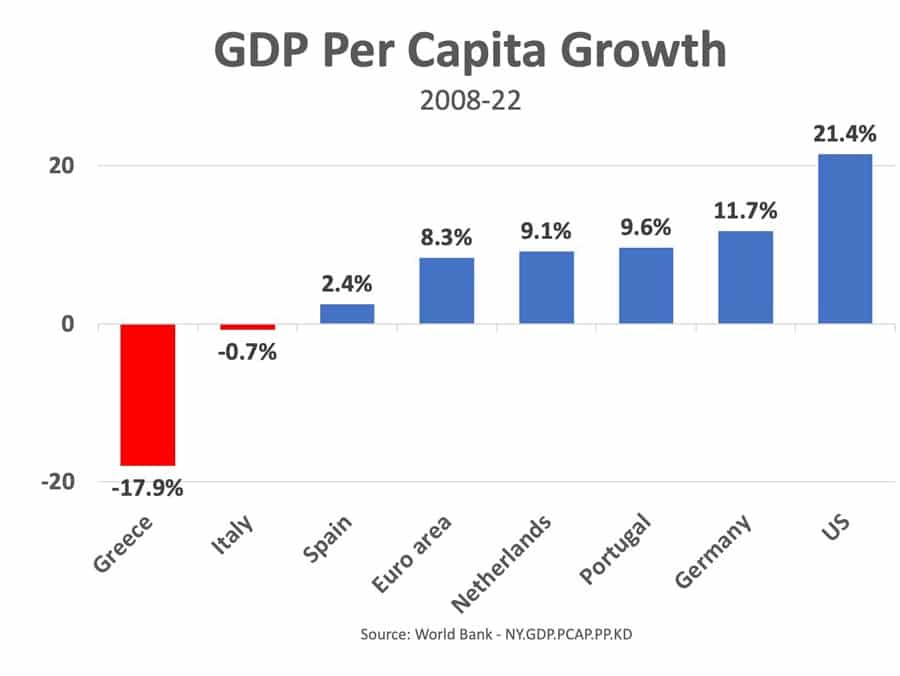

Well before we place the Greek economy on a pedestal, we do need to be cautious about the use of economic statistics. The dark truth is that Greek is recovering from an unprecedented economic disaster. The Greek debt crisis saw GDP fall 18%, and unemployment soar to 25%. To put this into context, during the great depression UK output only fell 5%. Even now, the Greek economy is still below its 2008 peak. If 20% of your economy shuts, down, you would expect to see faster growth as the economy recovers and this explains some of Greece’s recovery

In fact, the first lesson the UK can learn from the Greek economy is the potential dangers and pitfalls of a single currency, especially when your economy diverges from the rest of Europe. The New Labour government have made encouraging signs of closer co-operation with Europe. But, to rejoin the EU and in theory have to join the Euro seems an impossibility.

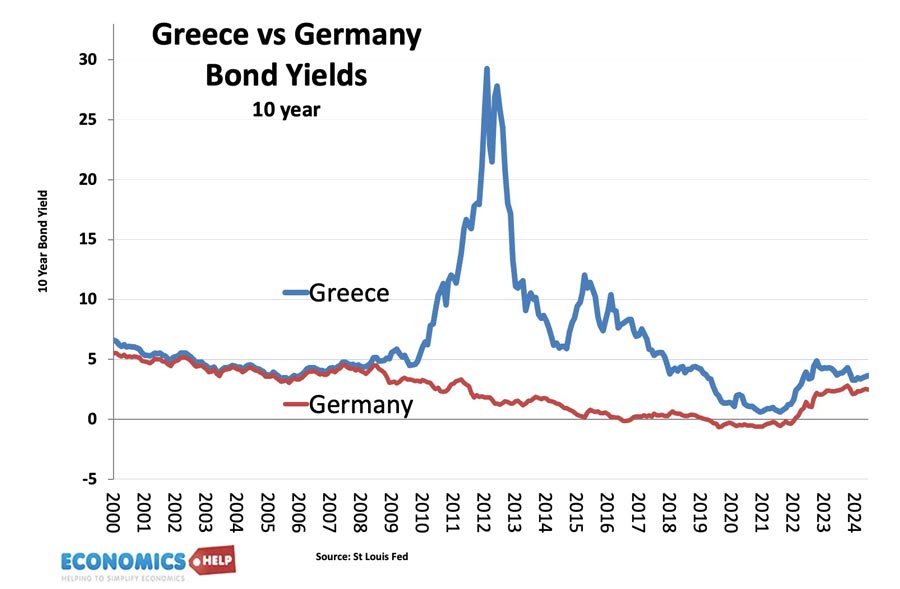

In the early years of the Euro, countries like Greece, Spain and Portugal all seemed to get the benefits of the Euro without any drawbacks. Bond yields converged as credit rating agencies, incorrectly as it turns out, believed debt was safe in any currency denominated in the Euro. This proved to be false optimism. Not only that but, the Euro allowed wild imbalances to occur, and nowhere was this greater than in Greece. The Greek economy had never really industrialised and consumer goods were mostly imported. The Greek current account deficit reached 15% of GDP in 2008, the UK by contrast was around 3%. But, the real problem of the Euro was the next stage. The global recession of 2008, led to a slump in tax revenues, debt rose and EU creditors wanted repaying. But, the Greek economy was broke, debt was over 140% of GDP, and the economy was deeply uncompetitive. It was actually a similar story in the UK, the global recession hit the UK economy really hard because of its reliance on finance. The difference is that the UK saw a 30% devaluation in Sterling which helped boost domestic demand, In the Euro, Greece couldn’t devalue at all. Secondly, the UK had its own monetary policy, interest rates were slashed to 0% and quantitative easing started, helping to make it cheaper to borrow.

Whilst UK bond yields fell, Eurozone bond yields surged. But, it got worse because Greece was told by the EU that it must pursue austerity, cut spending and increase taxes to reduce its high debt. It was a perfect storm for economic disaster. Greece was being asked to restore competitiveness basically through a massive recession and fall in wages. The austerity measures were so severe they started a vicious cycle of falling output and falling tax revenues. By, contrast the UK austerity was really quite mild. True spending was cut in many departments and the fiscal austerity led to lower growth. But, Greece was off the scale.

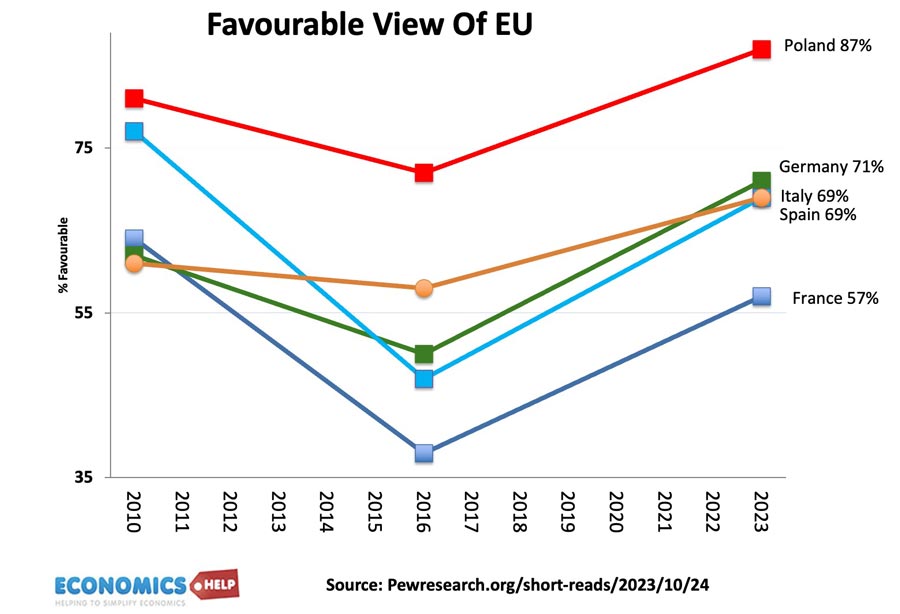

If Greece was a cautionary tale about the Single Currency, the UK made its own contribution to the European project by making Euroscepticism more unpopular. By 2016, there was a continent wide rise in euroscepticism in part caused by the devastating Euro debt crisis of 2012. But, Brexit and the UK’s economic and political difficulties, showed quite a sharp reversal in the fortunes of attitudes to Europe.

Greece Recovery

Ironically, after all the EU encouraged austerity of the early 2010s, Greece has been a major beneficiary of the Covid recovery funds. Since 2021, Greece has received nearly 15 billion euros in grants and loans from the EU – equivalent to about 8% GDP. This has been enthusiastically taken up by the Greek economy, which has sought to diversify away from a reliance on tourism. It has attracted investment from multinationals like Microsoft and Pfizer. Greece’s investment has boomed from 10 to 15% of GDP, which has increased economic growth. But, again, the main point is that at 10%, investment was incredibly low to start with a reflection of the economic depression Greece suffered. However, it seems the EU has learnt from the debt crisis, the ECB is more flexible and the pandemic recovery funds have proved effective, especially for Italy and Greece.

Austerity

The UK government want more growth, but are timid about fiscal rules. The Greek experience shows the best way to see a reduction in debt to GDP is not just austerity but more investment. From the depths of 2015, Greek debt has fallen, helped by improved tax collection and some government reforms. This has seen a very welcome improvement in their credit rating from junk to investment grade. The big lesson of the Greek disaster is how austerity measures can ultimately become self-defeating, and breaking this cycle of low growth and low investment is critical.

Work – 4 day or 6 day

An interesting contrast between the two economies is on the issue of work. The UK’s campaign for a four day working week claims 92% of firms who took decided to continue in some form. Greece by contrast has passed a law that gives firms the right to make workers in some industries work a 6 day week. In fact, Greece has the longest working week of any country in Europe. Yet, is a long working week something to aim for? A problem for both economies has been productivity growth. UK productivity growth has been poor in past 15 years, and Greek productivity is amongst lowest in Europe. Real economic growth and prosperity come from capital investment which enables higher productivity. It is fairly unconvincing to think that working longer hours will do anything to boost productivity. Also, whilst Greeks might work long hours, that is only part of the story. Despite recent improvements, unemployment is still above the European average. Greece pension spending is one of the most generous in Europe. In the UK we worry about spending too much on pensions at 5% of GDP. Try 16% which is what Greece spends.

The Greek recovery shows that eventually economies can recover, if they are not crushed by uncessary problems. It also starts to show the Euro and the EU in a relatively better light than the depths of the 2015 crisis. However, to really understand the Greek crisis and what they went through, check out this video which goes into more detail about this extraordinary story.