The UK housing market is a nightmare for first-time buyers. Average deposits £47,000. House prices eight times income, and for renters it’s even worse with rents remorselessly rising. But, there’s a new government and they have pledged to build 1.5 million homes in the next five years. Assuming they can achieve this goal, which is a big assumption, will it actually reduce prices? Is building more houses and concreting the greenbelt the only way to fix the UK Housing crisis?

Basic economics suggests that a rise in supply of a good leads to a lower price. Yet, when it comes to the housing market, not everyone is convinced. The problem is that housing is different to a tradeable commodity like coffee or oil. You can’t short the housing market, in fact the average time to sell a house is currently 9 months, and more than other goods, prices are determined by other factors like interest rates, average wages and mortgage availability. These are the four main factors, affecting house prices and it can be difficult to isolate. We shall see how supply does affect prices, but not quite how we might expect.

Impact of Supply on Price

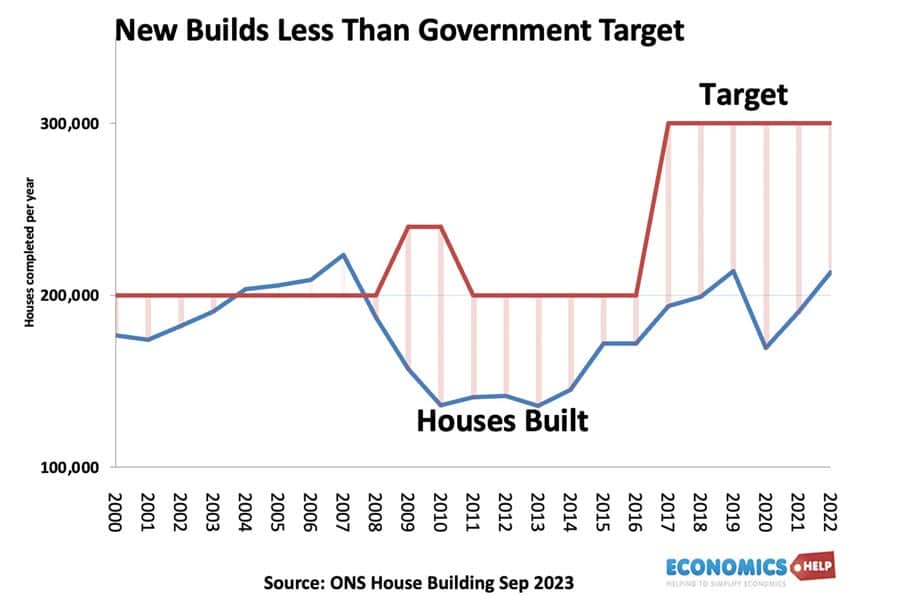

As a rough rule of thumb, different academic studies suggest that for a 1% increase in housing supply, house prices would be around 1-2% lower than otherwise. In 2022, there were 30 million dwellings in the UK. Increasing supply by 1.5 million would raise this housing supply 5%, and in theory cause house prices to be 7.5% lower than otherwise. But, that doesn’t mean house prices are actually going to fall 7.5%. To explain it – This is analysis by Lichfield shows the impact of building houses at the rate of 330,000 compared to current trends of building under 300,000. In their analysis prices would rise at a slower rate, but you can see there is no magic improvement in affordability. This doesn’t mean we shouldn’t build houses, because there are many long-term reasons. But, when people say building houses won’t cause prices to fall, they are likely to be right in one sense. But, it’s not the whole story.

How Many?

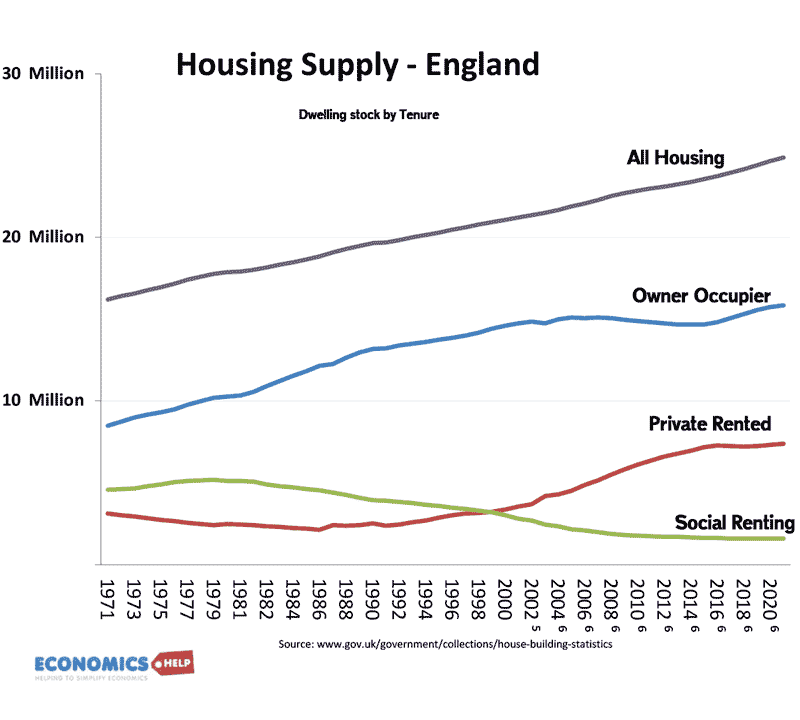

But, if prices won’t fall building 300,000 does that mean we would have to build half a million houses a year? There are a few factors to consider. Firstly, you don’t have to build more houses to get more dwellings. Between 2007 and 2023, England built 2.9 million houses, but dwellings increased by 3.3 million. That is an extra 406,000 properties through extensions, converting business properties and innovative use of buildings.

Now converting local businesses to housing is not necessarily great for communities, it is one criticism of gentrification, but sometimes there can be quite creative sources of housing. Living on a canal boat, even this converted skip – a symbolic protest against the broken London Housing market. Secondly, when looking at the housing market it is important to look at regional markets, and not just the national picture. The most extreme house prices in the UK are precisely in the areas where it is difficult to build. If you compare American cities, Austin Texas has very few restrictions. California and London do have restrictions, you can see the big difference in house price trajectory. This graph shows the relationship between rent increase and increase in supply. Generally higher supply leads to lower rent increases. It is worth mentioning the rented sector often reacts quicker to supply and demand than the buying sector.

We can see supply does have an impact on price, but a bigger effect is what happens to wages, interest rates and mortgage availability.

Future Prices

If we take the mortgage market first, since the credit crunch, new rules about stress testing mean buyers have to prove they can afford if interest rates rise. These rations demand more than the pre-credit crunch. It is one reason why higher interest rates haven’t caused a flood or repossessions and properties coming onto the market. It is one reason why house prices so far haven’t fallen as much as in previous crises like early 90s and 2008s. The outlook for interest rates is still mixed. Headline inflation has fallen substantially. However, service sector inflation is still a problem. The Bank are reluctant to cut rates, especially as there are signs of some economic recovery. It means that affordability constraints will remain stretched. As a share of income, mortgage repayments are quite high by historical standards. This will have a bigger impact on limiting price rises than building lots of new houses. Of course, when mortgages are expensive, there is always a temptation for the government to help to buy, which artificially boosts demand.

Reasons to Build

But, is building houses all about reducing prices? There are many other reasons to build, regardless of what happens to prices. Firstly, the shortage of housing in high-growth areas has acted as a brake on economic growth – especially in the south east. The UK has a relatively low vacancy rate – close to 2%, compared to say 10% in the United States. In the past few decades, the UK has built at a much slower rate than our European peers. Centre for Cities, projects that this has led to a deficit of 4 million homes, this is based on the assumption of building at a similar rate to other European countries. This low supply of housing has other effects than just price. Firstly, it changes household formation, encouraging young people to live with their parents for longer, bigger households. Secondly, a shortage of rented accommodation, especially social housing has led to record high homelessness in the UK. And this raises an important question. If the UK does build more houses, how many of these will end up in the privately rented sector? Due to rapid migration and a growing population, there has been a sharp rise in demand for renting, that has caused rents to rise. This is probably the worst aspect of the housing crisis.

Also, when we say building houses may only limit house price growth by 1%, it may not sound much, but over time, it can become cumulatively more significant. One LSE study suggests building 300,000 houses per year would cut prices by 10% over 20 years.

Will They Be Able To Build?

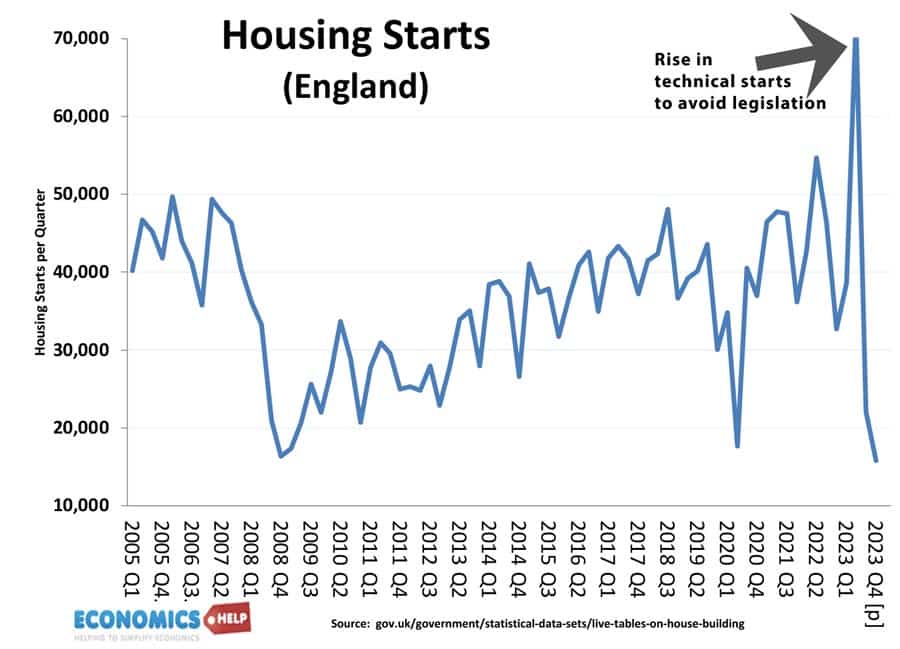

Perhaps the bigger question to ask is will the government actually be able to build 300,000 homes? There main hope is that by reducing the cost and difficulty of planning regulations, the private sector will be more motivated to build. But, there are few problems. Current rates of homebuilding are in decline. One of the biggest homebuilders Barratts recently announced disappointing plans to build less than expected. Homebuilders are reluctant to massively increase supply, if it means lower prices. And also They have complained about rising costs of production and shortage of skilled labour. To nearly double homebuilding requires a big rise in builders, perhaps more migration.

Other Solutions

There are other ways to limit the effects of the housing crisis. The most direct is to end the cuts to housing benefit. This has biggest impact in directly reducing housing costs. Secondly, the loss of social housing has done much to damage the privately rented sector. But reversing the decades of less social housing availability is a massive task.

IF all new houses are occupied by people needing homes (i.e. they are not second homes or just investments) then it must follow that 1.5 million homes will mean the number of people needing homes will be about 4.5 million (assumed average occupancy about 3) less than it would have been. Even if they are purchased by people already in homes, then as long as they sell their existing home, it still works. There are cases of homes standing empty, for financing reasons. That must be sorted out. As long as markets are allowed to work, building more homes must mean less homeless people, which is the real need. There is an issue that if deposits are high, landlords may have an advantage over buy to own (or maybe people with an advantage become landlords).

Can we suddenly increase home building? If we can suddenly train more brickies, electricians, breeze block output etc. etc. All the money in The World will not build houses.

Firstly its 1% ABOVE current rates needed to cover changes to population/households. So for prices in the UK to fall by 10% we’d need to build about 2.5-3 million additional homes. This would cost about £250bn to build plus the land. Whereas, changing poor tax choices by fully taxing land’s rental value would drop average rents and house prices by 65% overnight. And by facilitating radical reductions of taxes on output, not only increase the disposable incomes of typical working families, but take a huge deadweight off our economy.

Housing is a distributional problem with the returns to land. Changing that distribution indirectly by building lots of homes, rent controls and social housing are ineffective and inefficient mitigation policies.

The only way to solve housing issues is to do so directly via the tax system.