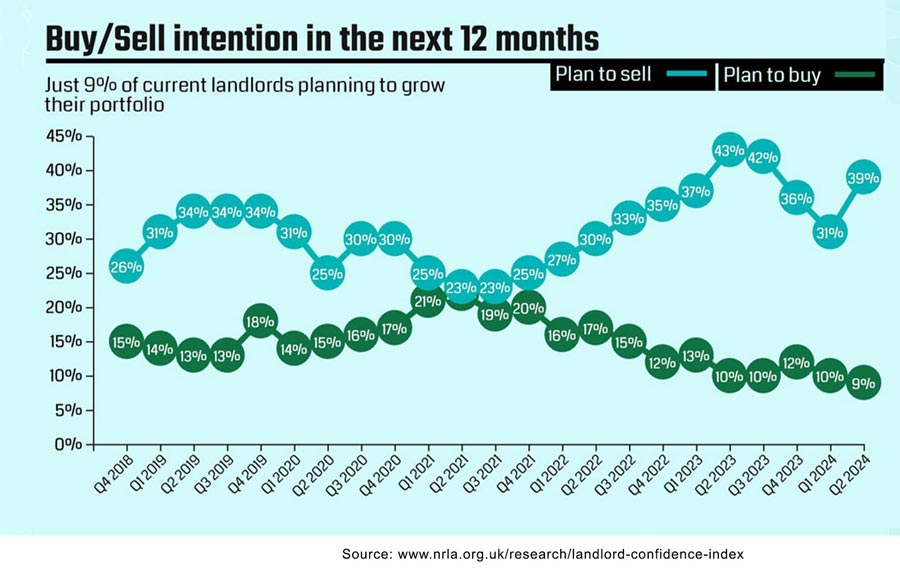

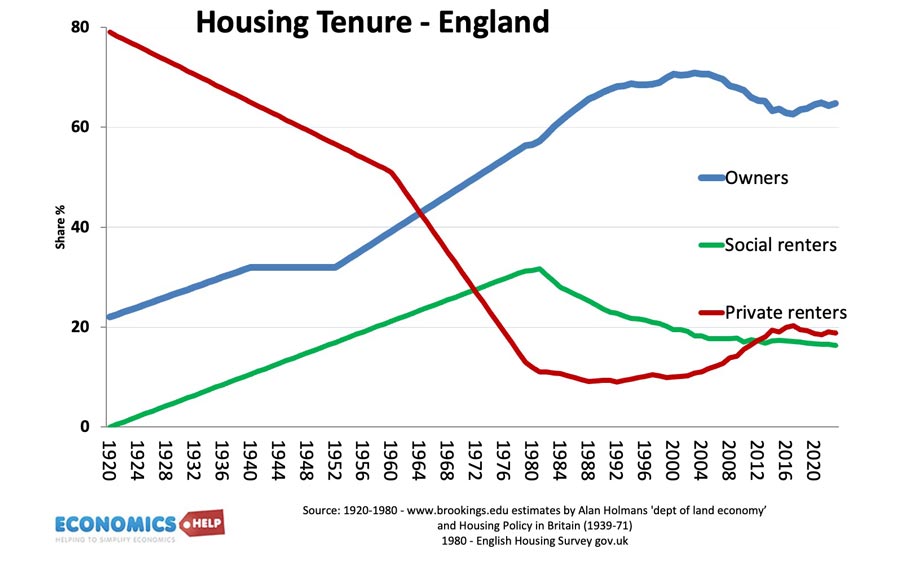

After the housing crash of 2009, many houses were bought at discount prices by buy to let landlords, and the share of buy to let rose to a record share of the market. But, 2016 was a turning point, with government legislation imposing higher tax rates on landlords in an effort to reverse declining home-ownership rates. Since then more tax and regulation changes, combined with higher interest rates mean there is no shortage of landlords who say they are planning to leave the sector, just 9% plan to expand their portfolio, and 39% plan to sell.

This is despite record rent rises, which are causing households to spend record levels of income on housing costs. Will the rental crisis get worse if landlords sell?

In June 2024, 18% of properties listed for sale, had been listed for rent in the past 3 years, that was a 100% increase on the previous year, so there is some evidence buy to let investors are actually selling.

Why Landlords are Selling, or at least not buying

The top reasons for selling are past legislation, higher taxes, proposed legislation and rising interest rates. Other reasons include an end to rapid house price growth.

In the past landlords could deduct mortgage interest payments from their taxable income. This has now been removed and is a significant increase in costs especially for landlords who pay the higher rate of income tax. One solution is incorporation as a business, but this typically requires a much larger portfolio. But, it’s not just tax, landlords claim that section 21 ending no fault evicitions makes it harder to get rid of disruptive tenants. Landlords are also concerned about new legislation around the corner. The government have confirmed that all rented properties must have an energy grade certificate of C or above by 2030. For some old Victorian properties, this could be prohibitively expensive, with 18% of landlords claiming it could cost more than £10,000. The logic of the government is that the UK has the worst insulated housing in Europe, contributing to a wastage of heating bills. But, landlords may prefer to sell rather than invest in reducing heat loss. Landlords also claim that they face a war of attrition with additional legislation such as easier to keep pets, removal of wear and tear allowance and deposit protection schemes. It doesn’t help that the reputation of landlords is pretty low.

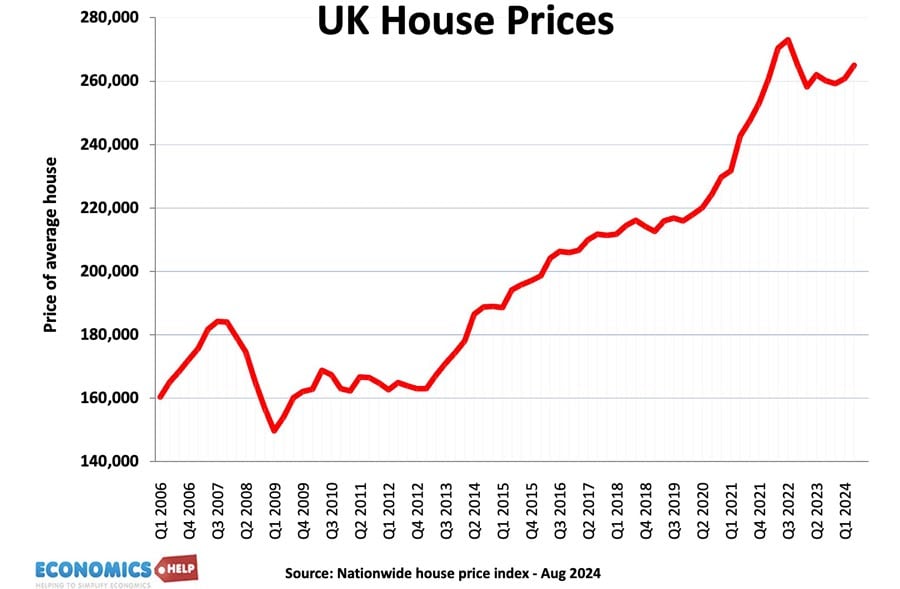

But, it’s more than legislation. Landlords who bought at the end of the 2009 crash were to see rapid capital gains in the next 13 years, a near 80% rise in nominal house prices at a time of poor investment returns elsewhere. The problem is that the UK has seen five decades of real house price increases, but it has left a market at breaking point with house prices near 8 times income levels. Even if prices are propped up by wealthy parents helping with deposits, the prospect of another sustained boom in real house prices is remote, even for the most optimistic forecaster. If you can’t rely on easy capital gains, you are left with just the profit from rental incomes. On the one hand, rents have been rising faster than prices and earnings. It should be a landlord dream to be able to keep setting higher rents. But, for a buy to let investors on an income only mortgage, the monthly mortgage costs have risen even more substantially. In 2020, with interest rates at 2%, a £200,000 interest only mortgage was £334. By 2024 with interest rates at 5%, the same interest only mortgage has increased 149% to £834 a month. The basic buy to let mortgage is now above the average rental yield. In the short-term some landlords are still on low fixed rate deals, but as they face remortgaging to higher rates, the jump in mortgage costs will be greater than even the increase in rents.

Are Landlords actually selling?

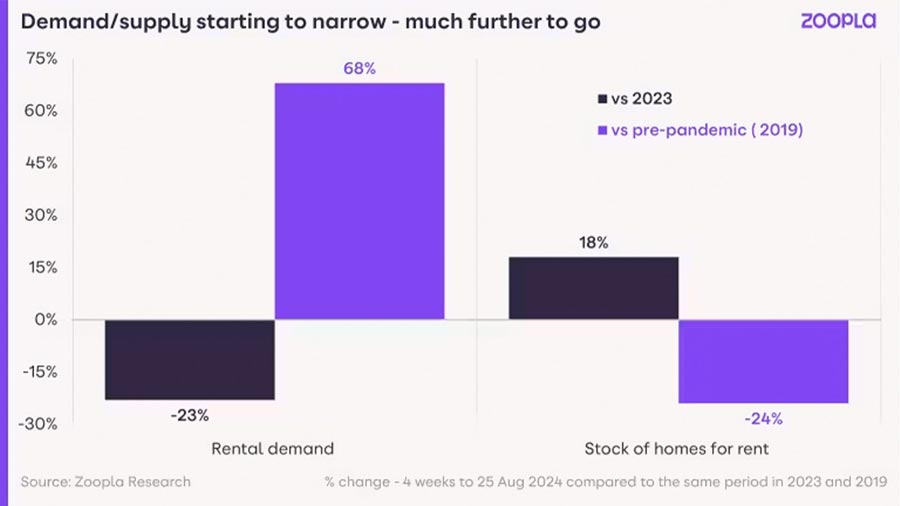

For all the talk of landlords selling up, what is actually happening? I remember covering this in 2022, and despite the talk of landlords selling, the mass exodus is often exaggerated. This comes from the industry itself, which understandably uses the threat of leaving the market as a bargaining chip to avoid regulation and tax rises. Secondly, if we look at the number of people living in the private rented sector, the number is relatively stable. There is a fall in new but to let mortgages taken out. But, there is no massive exodus. What has happened is that demand has risen much faster than supply. So in this context, a stagnation of supply is actually a real problem. With a rise in population, we need to be increasing the supply of private rented accommodation not keeping it the same.

Zoopla report that the number of available rented properties on the market is stil 25% lower than pre-pandemic. This is because existing renters are more likely to stay put and keep their deal. It means the growth in new renters are facing fewer and fewer properties coming onto the market, and this is why we hear the crazy stories of 50+ enquiries per property and bidding wars to get a property in key locations.

New Landlords

Although statistics are harder to find for the rental sector, this is reasonable evidence that large commercial property companies, such as ISA and pension funds are buying up property wholesale. Foreign investors are also increasing their portfolios not worried about UK tax changes which are more targetted at UK residents. However, even the Bank of England admits it is hard to know for sure how many are being bought up. The fundamental problem is that house building has stalled, falling well behind government targets. The new government have bold plans to reform planning and make it easier to build, but it will be time-consuming to get momentum in the house buidling sector. The problem is the UK faces a backlog of housing shortages

What Happens when they sell?

Also, if landlords sell, the number of properties is still the same, and houses don’t disappear, what happens, is that it increases the supply of houses on the market, and in theory, help first-time buyers from the rented sector to buy their own house. After all this was the logic of past government reforms. Certainly, there is evidence that moderation of interest rates has seen more first-time buyers enter the market and buyer demand is stronger than last year.

However, although this is true to some extent, it is not without issues. Firstly, housing density tends to be higher in the private rented sector than owner occupied. A rented accommodation may support four independent adults. A house may support a single person. Secondly, selling houses from private rented sector is good for those renters who are close to the financial border of being able to buy, but it is bad news for low income households who either lack parental support or high income. Official figures suggest it is a real problem that people who lose their private rented accommodation when their landlord sells are unable to get a new rent. Perhaps because new market rents are much higher than their old deal. Data suggests four in 10 families who have asked councils for temporary housing is due to landlord selling. The UK has seen a record rise in homelessness defined as insecure housing, the crisis in the private rented sector is definitely a big part of this problem.

In 1920, 80% of households were in the privately rented sector. This steadily fell for 60 years. In the 1970s, the government regulated the renting sector strictly and many landlords sold up, but local councils often bought up these houses and converted them to social use. It created a housing market much more affordable for low-income households. The question is could this be replicated? Certainly prices are much more expensive in real terms, and bankrupt councils don’t have the funds to buy up properties for low-income rent. Is there any hope that house prices may fall in the future and become more affordable over time. This video looks at prospects for prices in short and long-term

Not entirely sure that the move to social homes in the post war years actually reduced rent Many London tenaments that were demolished resulted in tenants paying more for their social homes. That said, maintenance on the old tenaments was expected, in many cases, to be done by the tenant which in some cases compensated for the higher rents of the social homes. Interestingly, many tenants expressed regret at the loss of their old homes and the sense of community when they moved to the new estates.