Ireland can lay claim to be the third richest country in the world.

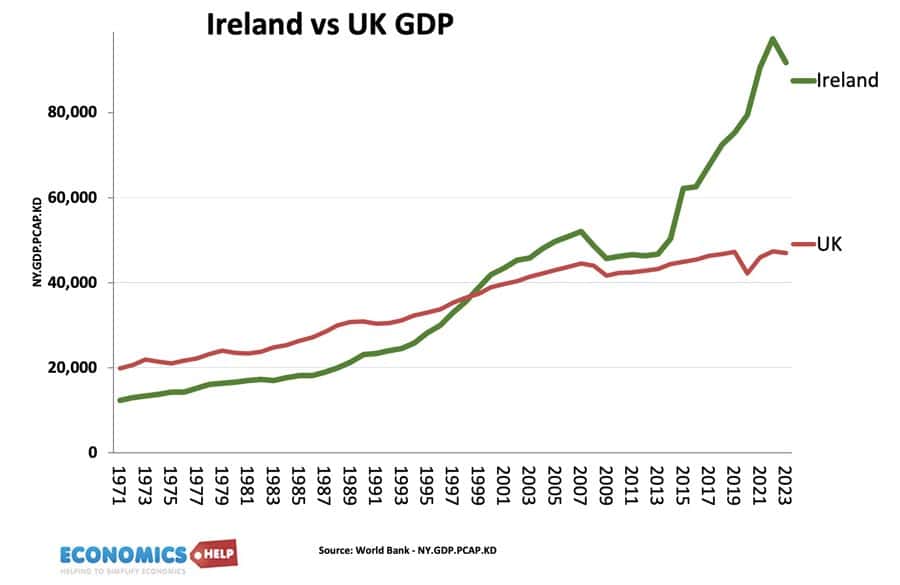

In the 1970s, Ireland was one of the poorest countries in Western Europe, largely agrarian and with real incomes that lagged its neighbour across the Irish Sea.

But, then over the next few decades, the Irish economy started to grow faster than the UK. It was helped by joining the EEC, attracting inward investment and the growth of large-scale farming enterprises. But, what really supercharged Irish growth was ultra-low corporation tax.

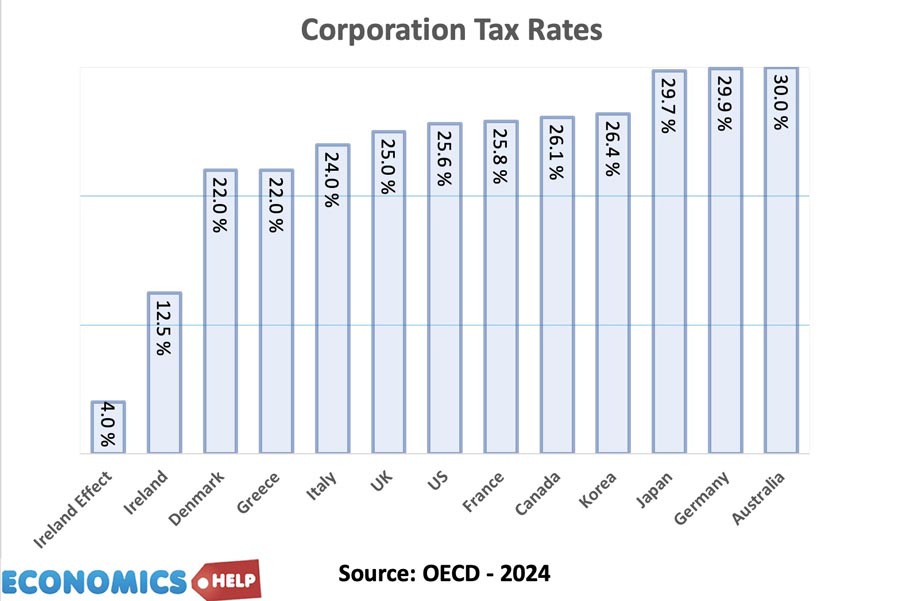

In 1997, the corporation tax rate was cut to 12.5% which gave Ireland a competive advantage over other European countries. Whilst the headline tax rate was 12.5%, in practise, with all the exemptions, the effective tax rate was just 4%. With the EU claiming the likes of Apple were given an effective corporation tax of just 1%.

The low tax rate was particularly appealing to American multinationals who could avoid paying US tax by shifting intellectual property rights to Ireland. It didn’t matter if the goods were not produced or sold in Ireland, it was just an effective accounting trick.. The effect was to supercharge Irish GDP. It is important to bear in mind, American investment wasn’t just about accounting tricks, it did lead to real investment and real jobs. In 2017, US firms directly employ 25% of private sector jobs, paid 80% of corporation tax, paid 50% of Irish income tax, parly due to offering much higher paid jobs than typical. The investment has also had knock on effects, such as creating a boom in services, in particular financial services, accountants who can offer innovative ways to avoid corporation tax are in particular high demand.

Lies, Damned lies and GDP Statistics

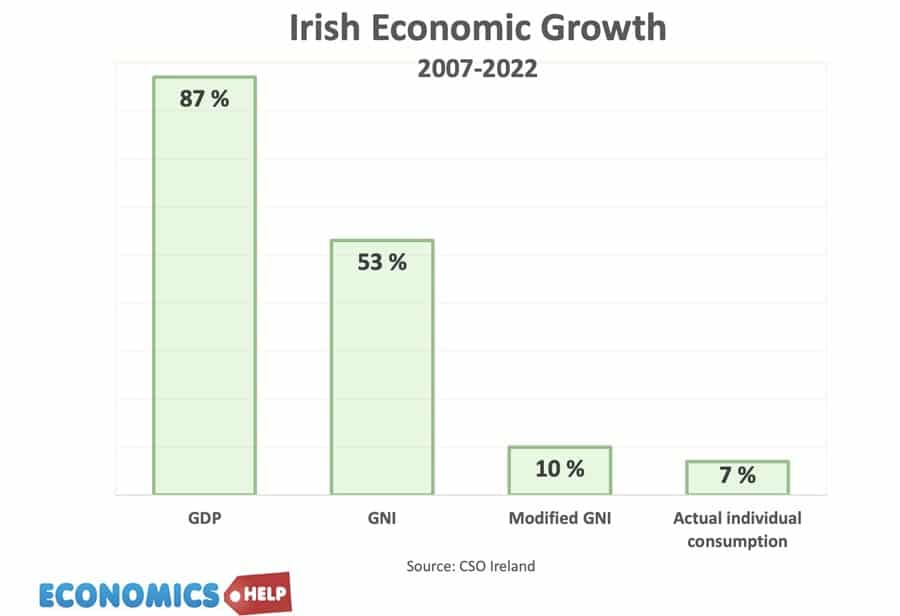

Ireland has the world’s largest flows of BEPS base erosion and profit shifting in the world. Bigger than the entire Carribean system noted for its tax havens. This is all great for increasing GDP. But, the growth in Irish GDP is deeply misleading to the economy ordinary people face.

Between 2007 to 2022, Irish GDP per capita increased by 87%, Gross national income by 53%, and modified GNI per capita the preferred measure of Irish government just 10%. Without getting too technical modified GNI, excludes all the accounting tricks which inflate GDP, but don’t translate into higher living standards for ordinary people. Actual individual consumption only increased 7%, which is what actually matters. During the Brexit debate, there was a famous quote where a leave voter heckled an economist – it’s your GDP not mine. No where is this statement more true than in Ireland.

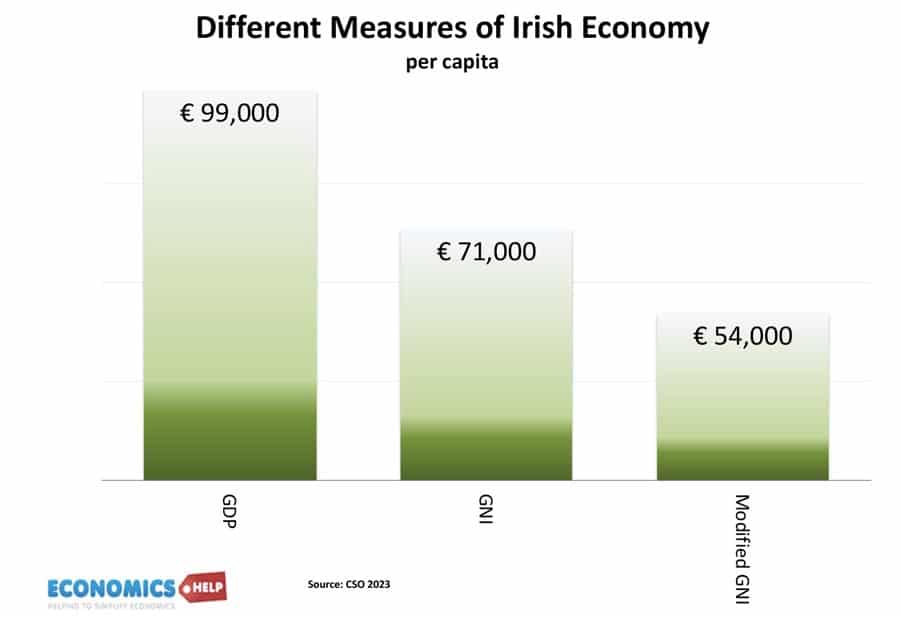

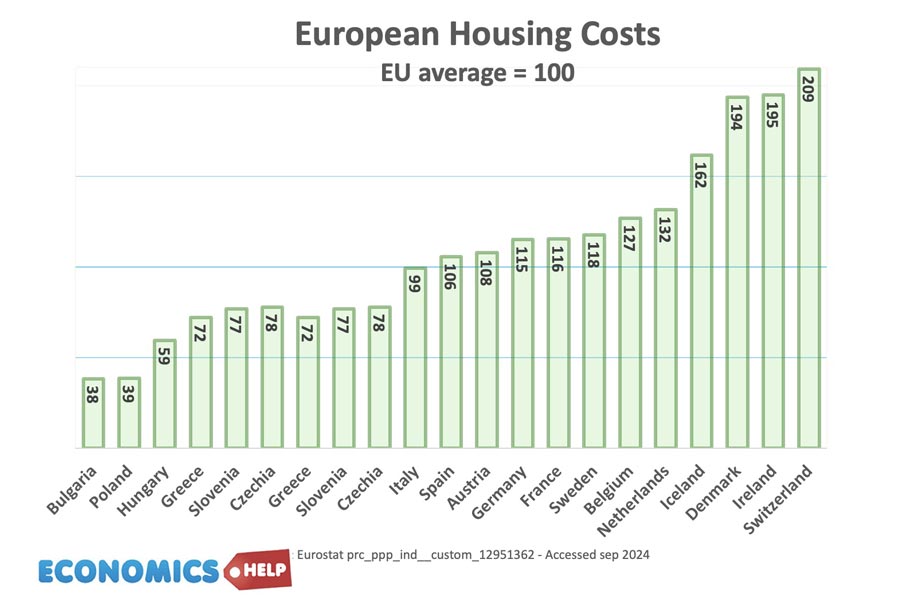

If we look at Irish GDP per capita, it is an amazing €99,000. GNI per capita is €71,000, but modified GNI just €54,000. And again the best measure of living standards is what can you actually buy. And Ireland is one of the most expensive places to live in Europe. 2nd only to Switzerland and double the EU average.

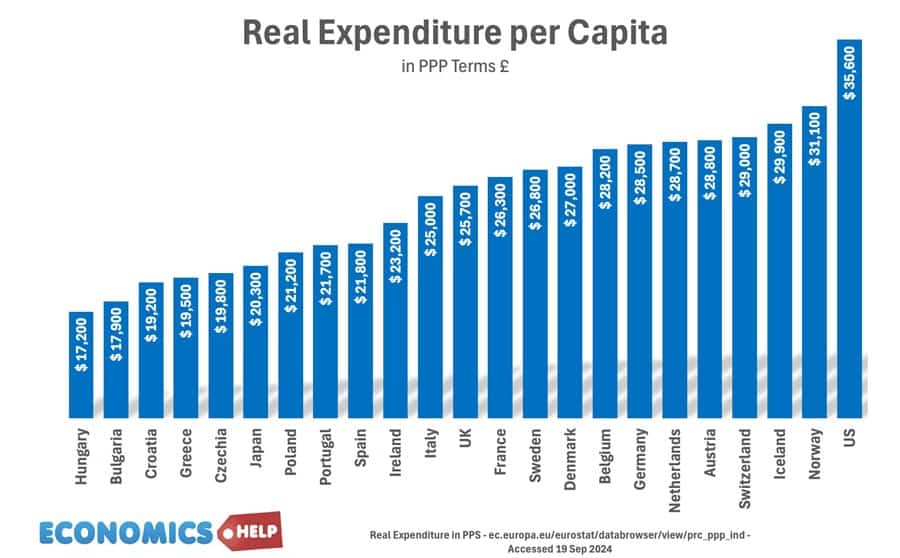

This shows real expenditure per capita adjusted for purchasing power parity. On this measure Ireland is actually lower living standards than Italy and the UK. This is a better reflection of the living standards Irish people are actually experiencing.

Wages

Also, there is something of a two speed economy in Ireland. The average salary from an American multinational is €85k. For a domestic industrial job it is €35k. Eurostat estimates that in 2022 the top 20% of Irish earners took 15 times more market-based income in than those in the bottom 20%. This is the highest rate of income inequality in the EU. Though, it is important to bear in mind, the irish tax and benefit system does much to reduce this market inequality. Once tax and benefits taken into account Ireland is closer to the EU average for inequality.

Housing Crisis

But, this still doesn’t take into account housing costs. No where is this cost of living crisis as acute as housing, where the average Dublin rent is €2,102 a month. That is equivalent to the entire monthly take-home pay of a newly qualified teacher.

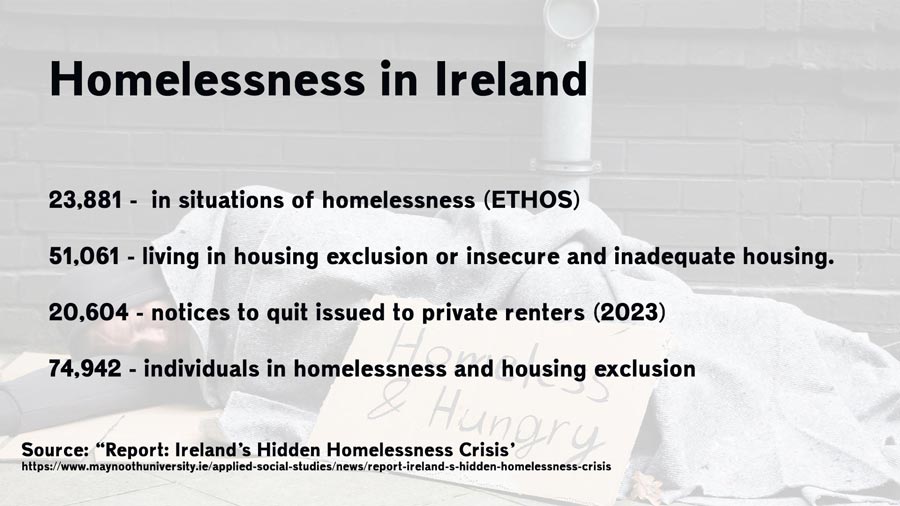

With rents unaffordable, there has been a rise in evictions and an estimated 74,942 individuals in homelessness and housing exclusion. Home ownership rates have fallen not surprising given house prices are nearly 8 times income. But, it raises the question how can you have such a bad housing crisis, when GDP is north of $100,000 per capita?

Why Housing Crisis?

Like the UK, since 1973, social housing has been sold off and not replaced. An estimate 2/3 of social housing is now in the private sector. 58% of new homes for rent has come from private global investment funds, who have prioritised more expensive propperties. Thirdly, whilst corporation tax is low, tax on rent is either 20% or 40%, which landlords pass onto tenants. Landlords also complain about expensive regualtions. Fouthly during the boom years of the early 2000s, it precipated a speculative bubble in Irish housing, prices soared and so did building. When the financial bubble popped Ireland was uniquely exposed, there was oversupply, prices fell 50% and house building sector contracted. It has never really recovered. Despite failings of the private sector, the government has been curiously reluctant to invest in housing.Government policy has focused on attracting multinational investment. US companies have been given favourable options to purchase land in favourable locations for their operations, less thought has been given to the brewing housing crisis.

No Tax Please, We’re Irish

Just recently, the EU’s highest court recently ruled that Apple must pay Ireland over €13 billion in back taxes, but the Irish government didn’t want it. Whilst UK is squabbling over a fiscal black hole and cutting winter fuel allowance for vulnerable pensioners to save £1.6bn, Ireland is literally swimming in money, a rare budget surplus, an embarassment of riches, yet at the same time young people are leaving the country in despair of the cost of living.

Surely if you have a housing crisis, why not use the budget surplus to invest in building affordable homes, or at least offer help with housing benefit or reduce medical costs. The government’s argument is that with the economy close to full employment, it doesn’t have enough workers and resources to build houses. This is strange because in the housing boom of the early 2000s, it was eased by migration of builders from eastern Europe. Perhaps a deep reason is the fear of repeating the mistake of 2008, when a reliance on housing construction and tax revenues from the boom led to a spectacular crash, and severe austerity. An austerity which fell mainly on more vulneable groups of society.

Low tax was not the only reason multinationals were attracted to Ireland. It has a unique position as an English speaking entry into the European Single Market. Ireland has strong historical ties with the US through past migration. It meets many of the criteria for a stable economy. But, at the same, time, if you take away low tax, Ireland does not rank particularly well on other metrics. FDI ranking is nothing special, and on World Bank Competitiveness index, it ranked just 24th. Since Brexit is has surprisingly done little to attract financial firms from London, who have moved to Paris or Frankfurt. And finally the cost of living crisis is contributing to labour market inflexibility and shortage of workers in fast growing regions.

The Irish government is also worried that the gravy train of being a tax haven may becoming to an end. The US is starting to reform its tax system giving less incentive for the likes of Apple to report profit abroad. There is growing pressure for a global minimum corporation tax rate of 15%, which reduces Ireland’s temporary competitive advantage. It is not that Apple are suddenly going to leave Apple because of changes to tax rates, but the future growth and tax base needs to be broader as the years of massive FDI slow down.

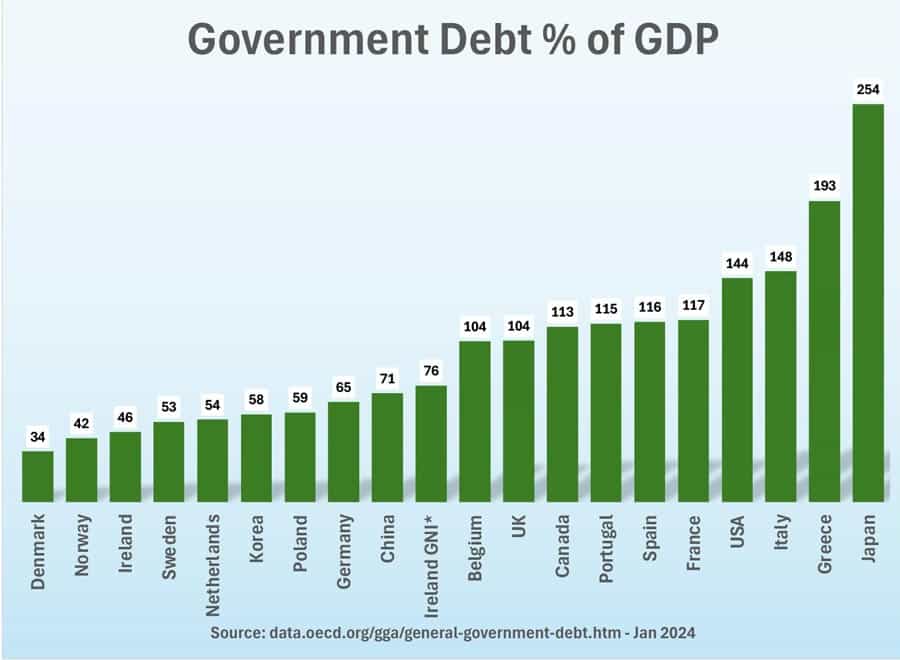

During the financial crisis, Ireland saw a large rise in public sector debt. If we use debt as a share of GDP it is quite low, but this is misleading, if we use GNI, debt is higher. Still, it is strange to sit on a budget surplus, when there is such a clear need to deal with the over-riding social problem of unaffordable housing. Despite the discrepancies of GDP, the Irish econony has made some progress in recent decades. But, it could do so much better if the housing crisis was eased. Still Ireland has done better economically than the UK, which has stuggled to get over the problems created by Brexit – this video explains why it is regretted by so many in Britain.

What specific policies could Ireland implement to address the housing crisis effectively?

As far as I know Ireland has experienced administrative delays in housing projects, especially in urban areas.