Faced with a black hole in public finances, the Labour government have announced an end to universal winter fuel allowance for pensioners. It will now be means-tested. It means 9.4 million individual pensioners will lose the £200-£300 a year allowance. It will save the government an estimated £1.6bn a year, which as we shall see is a drop in the ocean compared to the government’s £5 trillion worth of pension liabilities. Not all pensioners are poor. Around 50% of pensioners are in the top half of income distribution, and those who own a house and have paid off mortgage have lower living costs than the average household.

But there is a big problem with means testing. Firstly, many miss out on winter fuel allowance by being just above the means-threshold test. The current level of Pension credit is just £218.15/week. Income of just £220 a week, and you lose £200 a year.

Problem with Means Testing

It also penalises those who save for private pensions or work part-time to top up income. Means testing can give a sense of unfairness if you just miss the cut-off point. In the long term, it may reduce the incentive to privately save. The second point is that many who are eligible for pension credit don’t claim. An estimated 780,000 pensioners in England and Wales will miss out on winter fuel allowance because they don’t apply for the pension credit they are able to. In fact, if everyone eligible for pension credit actually claimed it, the cost to the government would be greater than the savings of £1.6 bn. What it means though is many vulnerable elderly people will miss out and be pushed into fuel poverty.

The government pointed out that in April, the state pension is set to rise £450 because of the triple lock pension guarantee. So even though winter fuel is removed, there is a net increase. But, there are three aspects which make this unappealing. Firstly, behavioural economics shows, we budget spending. A winter fuel allowance gives people the confidence to heat homes properly. Losing what we are used to is a big psychological loss. Also, the rise in state pension is needed for other cost of living pressures. The result is a huge political backlash, but the cost savings are really quite small.

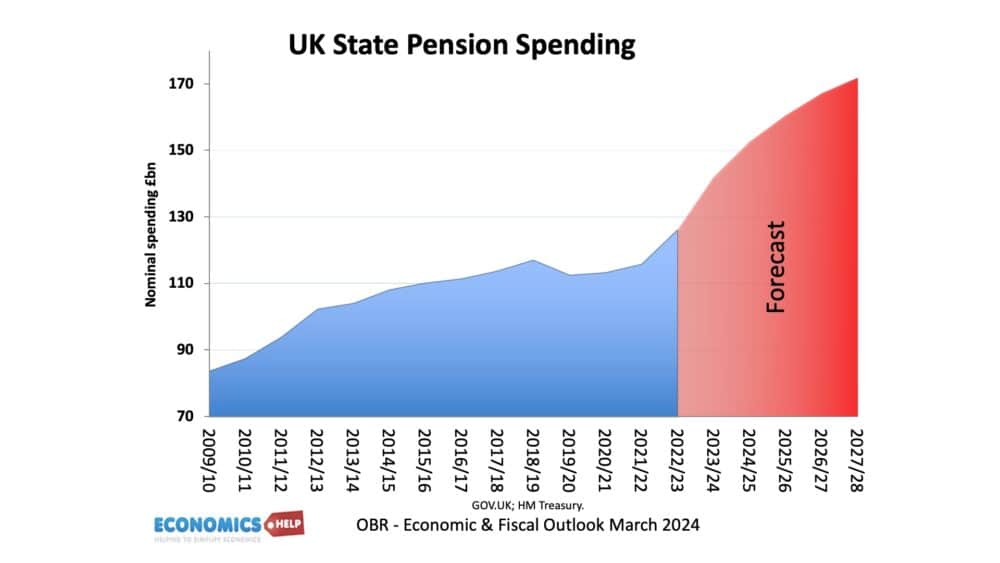

State Pension spending in 2022/23 was £126bn, but next year will rise to £152, by 2028 it is estimated to be £172bn.

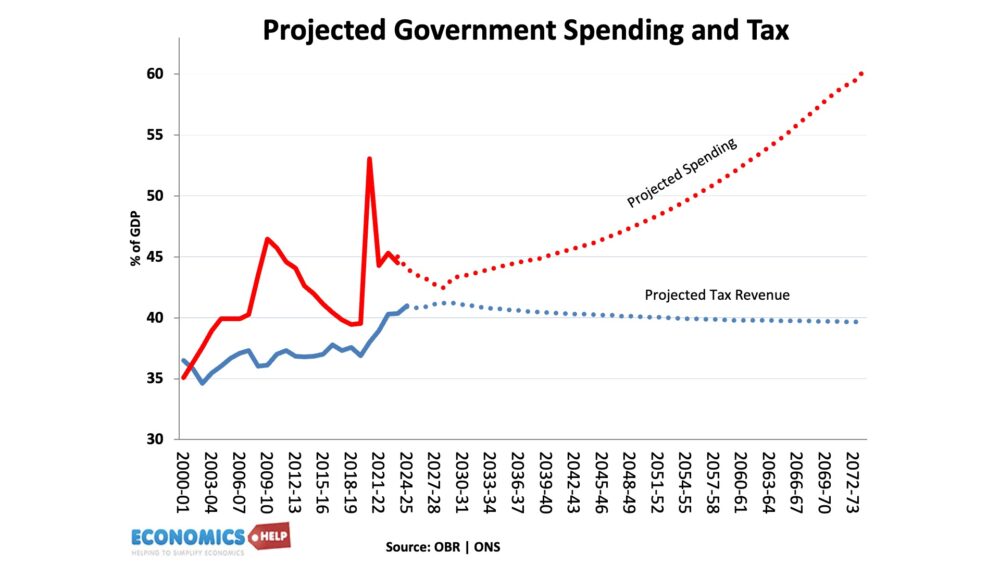

Looking further into the future, the OBR claim that on current policy, government spending as a share of GDP is expected to rise from 42% to 59% of GDP by 2070. This is clearly unsustainable without major change in policy. The problem is that the UK population is set to age, the share of the population over 65 is going to rise from 27% to 55% by the end of the century. Now this forecast is somewhat dubious, for some reason ONS assume zero net migration. But, there is definitely a very significant fall in fertility rates, people are living longer and having fewer children. The result will be an unwelcome combination of rising government spending and diminishing tax revenues. An ageing population means both higher state pensions but also rising health care, the share of spending on health care is forecast to rise to 13% of GDP. At the same time, with an ageing population productivity growth will tend to be lower. And The past 10 years suggest we are very unlikely to be able to grow our way out of the pension crisis.

Raise Retirement Age

One solution which has already been implemented is to raise the retirement age. In 1940, the retirement age was set at 60 for women and 65 for men. But, in the next few decades, life expectancy dramatically rose and so the cost of pensions rose. One study suggests that to make the UK pension sustainable, the pension age will have to rise to 71. This is a neat solution in that it makes a big difference to the cost of pensions. For example, just delaying the pension age rise to 67 will cost more than £60 billion.

The argument is that raising the pension age could also increase economic growth by increasing the labour force. Though when the pension age rose from 65 to 66 only 8% moved into paid work.

Problems with Raising Retirement Age

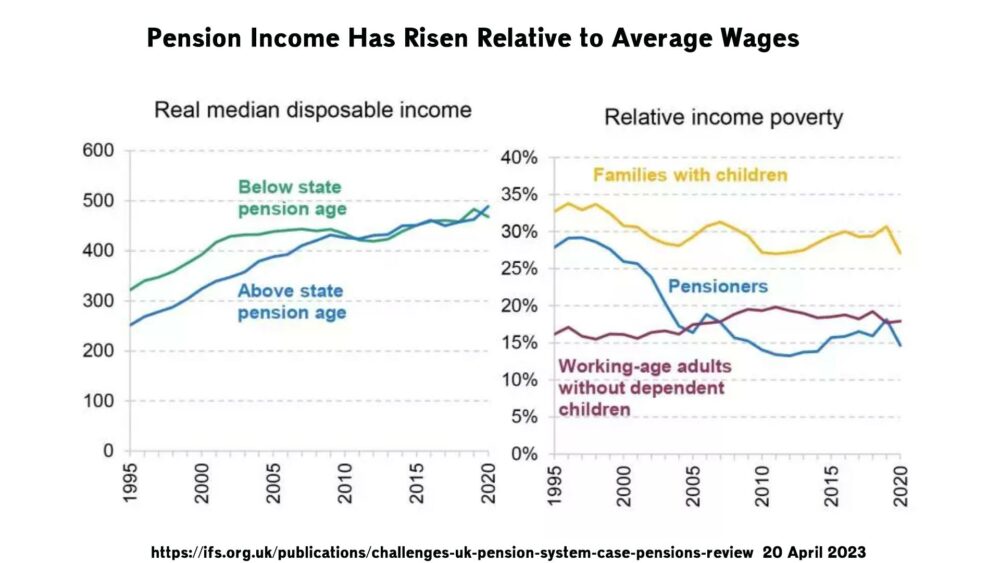

Increasing the pension age can only be implemented gradually. If people plan to retire at a certain age, it is unfair to suddenly increase. The IFS found raising the retirement age by one year led to a 25% increase in 65-year-olds in poverty. There is currently a 100% gap between benefits you can claim when of working age, and those when you are of state pension age. In recent years, pension benefits have risen much faster than working-age benefits. It is fair to point out, pension benefits have greater political visibility than working age benefits.

The other big issue is the number of people over 65 reporting poor health or some form of disability. Only 10% of population stay healthy into the over-70-year old category. This is the problem, the UK has seen a rise in poor health and a decline in health life expectancy, which really make it difficult to increase the retirement age. Poor health tends to be greater amongst low-income households. In fact, the hoped for rise in life-expectancy has started to slow, increasing the pressure to delay raising retirement age.

Housing Crisis

But, there is another coming economic crunch, that will make energy bills pale into insignificance. The UK pension model is based on the assumption pensioners will have low housing costs. Either owner-occupied with the mortgage paid off or living in subsidised social housing. But, the new reality of the UK housing market is that future generations are increasingly in the private rented sector. This presents a real dilemma, if you are paying market rent of £1,200 a month, it dwarfs the state pension income. It means the government will need to pay a big increase in housing benefits, just to avoid pensioners becoming homeless.

Triple Lock Guarantee

How has the triple lock affected pensioners? Since 2005 pension income has risen relative to the average working-age household. This reflects more a stagnation in average wages, than massive increase in pension living standards. However, the share of the retired living in poverty has declined. It was once the most at risk group, but has fallen. This is due to the fact the triple-lock pension has sometimes risen faster than real wages. In the past 14 years, pension income rose 9%, and non-pensioners rose 5.5% But, does that mean the UK pension is overly generous? UK UK pension spending is low compared to other countries – just 5% of GDP, compared to say 16% in Italy. The pension replacement rate is also relatively low around 50%. This means average pension income is 50% less than average earnings. It’s a big drop off in income, especially for those pensioners paying private rent.

The removal of winter fuel allowances was a poor decision. It negatively affects many low-income pensioners, it is politically costly and saves relatively little money anyway. A better solution would be like child-benefit, continue giving benefits to all, but claw back from high income households though the tax system. But, given projections for spending, something does need to change. But when the main political parties rule out any major tax rises, it will be difficult to meet spending, especially in a stagnating economy.

For example, if we are serious about meeting long-term rise in health and pension spending, Increasing VAT 1p from 20 to 21% would raise £7bn. (A 1p increase in the rate of VAT would raise £6.7bn in 2022–3 (0.3% of GDP)

This would probably be politically less costly than taking away £7bn in benefits that already exist. The uncomfortable truth is that if we want to maintain a decent state pension, and improve health care, with an ageing population you are probably looking at increasing the tax burden. The alternative is rising debt or privatisation of some public services. It’s not easy, but if you don’t like the idea of higher VAT or cuts to winter fuel allowance, there are ways to try and tax the rich, which this video looks into, so do check it out.

External Links

https://ifs.org.uk/publications/challenges-uk-pension-system-case-pensions-review

- your weekly income to £218.15 if you’re single.

- your joint weekly income to £332.95 if you have a partner.