Do you remember the days when you can afford to buy a house with a modest income and small deposit? I don’t. I’m middle aged, but the last time house prices were affordable, I was trying to buy football stickers rather than a 3 bed semi.

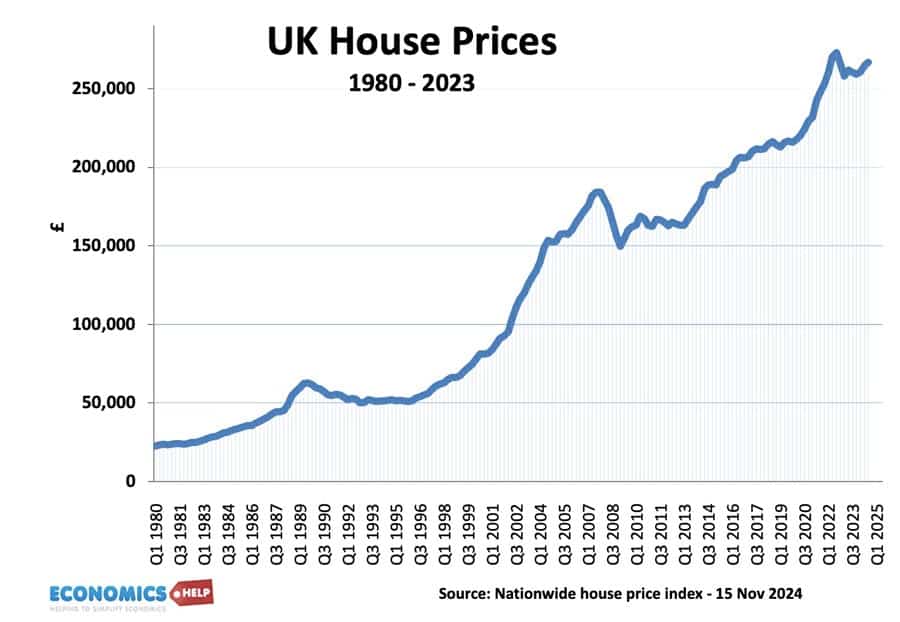

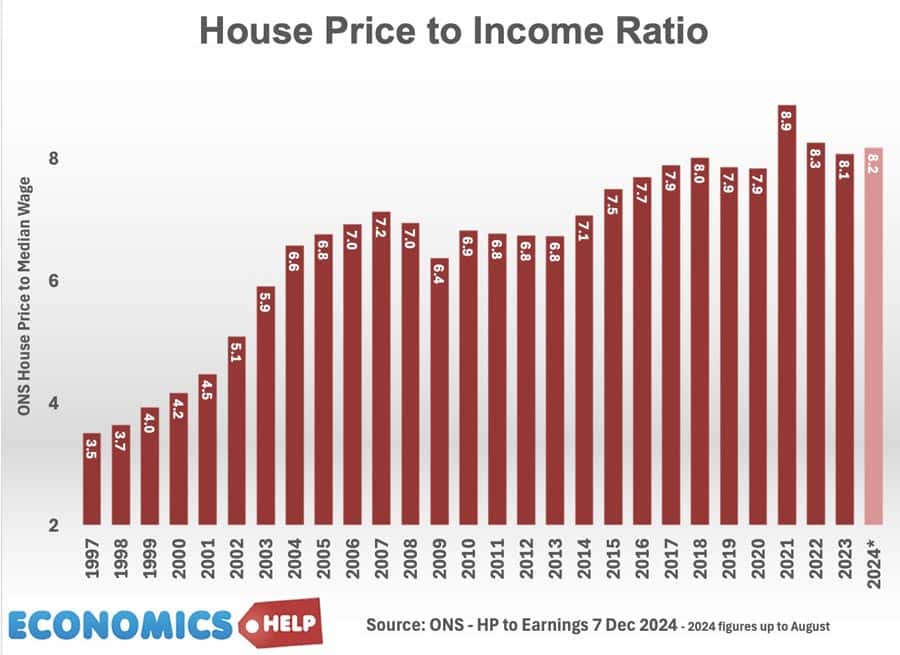

Since the early 1980s, UK house prices have increased 1,000%, and even if we adjust for inflation, house prices have risen 160% since the mid 1990s and 300% since the early 1980s. If we look at the ratio of house prices to income there has been no let up in recent decades. Since the early 1990s, house prices to income ratios have increased to over eight times, more expensive than the period of inequality between the wars. The last time house prices were this expensive, Charles Dickens was writing about the Victorian slums. Why is it that with economic growth, technological progress and supposed improvements, the most basic commodity has become out of reach?

1. Planning Restrictions

Firstly, the UK has significant restrictions and costs on building new house. Green belt restrictions are extensive, local authorities have veto power and then there are many rules and regulations about building height, quality of builds etc. The net result is that in the places where demand is greatest, and economic growth strongest, house building has not kept up. One study by Centre for Cities, suggests over 4 million homes are missing in the UK because of UK’s planning laws. The result is that the UK has one of lowest rates of home building in Europe, and this accumulation over 50 years has pushed up prices. One study by LSE claimed without the rigidity of UK planning rules, house prices in the southeast could be 30% lower in 2016.

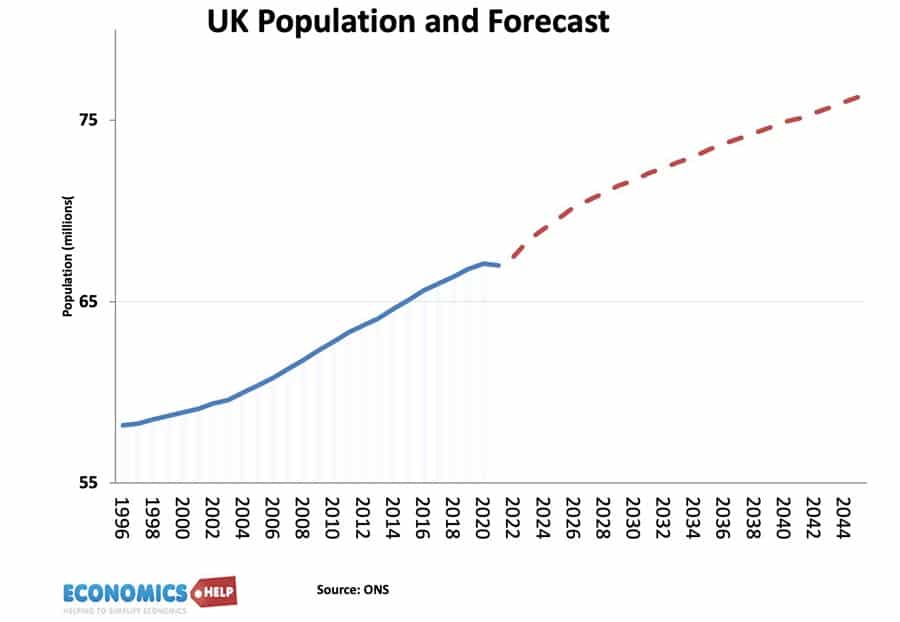

2. Population Growth

At the same time as home building has slowed down, the UK population has increased. An extra 10 million people in the past 20 years. And this population is forecast to rise. The growth in population is primarily due to high levels of net migration, in the past decades, net migration has been at record levels. Despite falling birth rates, the UK population is set to continue to rise in the future. And the number of households has been rising faster than the population, with more single occupancy households, such as old people living alone. With a backlog of missing homes, further rises in the number of households will make it hard to catch up. Don’t forget the housing crisis has suppressed household formation, e.g. people living with parents for longer because they can’t afford.

3. Private Sector not interested

If a shortage of supply is the cause of high prices, surely the government’s plan to build 1.5 million homes in the next five years will make prices affordable? If only it was that simple. Firstly, the government target is unlikely to be met. Government house building targets nearly always fail. There’s no reason to believe this will be different. Firstly, reforms to green belt, may not lead to many homes being built anyway. Secondly, the government is relying on the private sector, but the private sector have no incentive to build enough houses to make prices to drop. Their goal is profit maximisation and if that means sitting on permissions they are quite happy. Also, unfortunately, when government insist on requirements like 50% affordability, this only makes the private sector less likely to build any houses at all, affordable homes are less profitable

Don’t forget house builders are already sitting on 1.1 million plots with planning permission. Even if you built, 300,000 homes a year, some claim the reduction in price would be very fairly marginal. A 10% reduction over 20 years or 0.5% a year. It’s not enough. This is not to discourage building houses, but, it means it’s just about meeting a national target, but building where they are in greatest demand.

4. Underused Housing

So does that mean we have to concrete over Britain with houses to make them affordable? No. There are other issues. Firstly, we make bad use of existing housing supply. There are 600,000 empty homes and 8.8 million under-utilised. A retired couple with spare rooms have no incentive to downsize to smaller property, freeing up space for large families. Council tax rates are still based on 1991 values and high stamp duty increases the cost of moving. In recent years, the housing market has become more moribund as there is little incentive to move into more suitably sized housing. One solution would be to abolish council tax and stamp duty and replace with annual tax on the value of home. It would change the housing market, but it is too radical for UK politics.

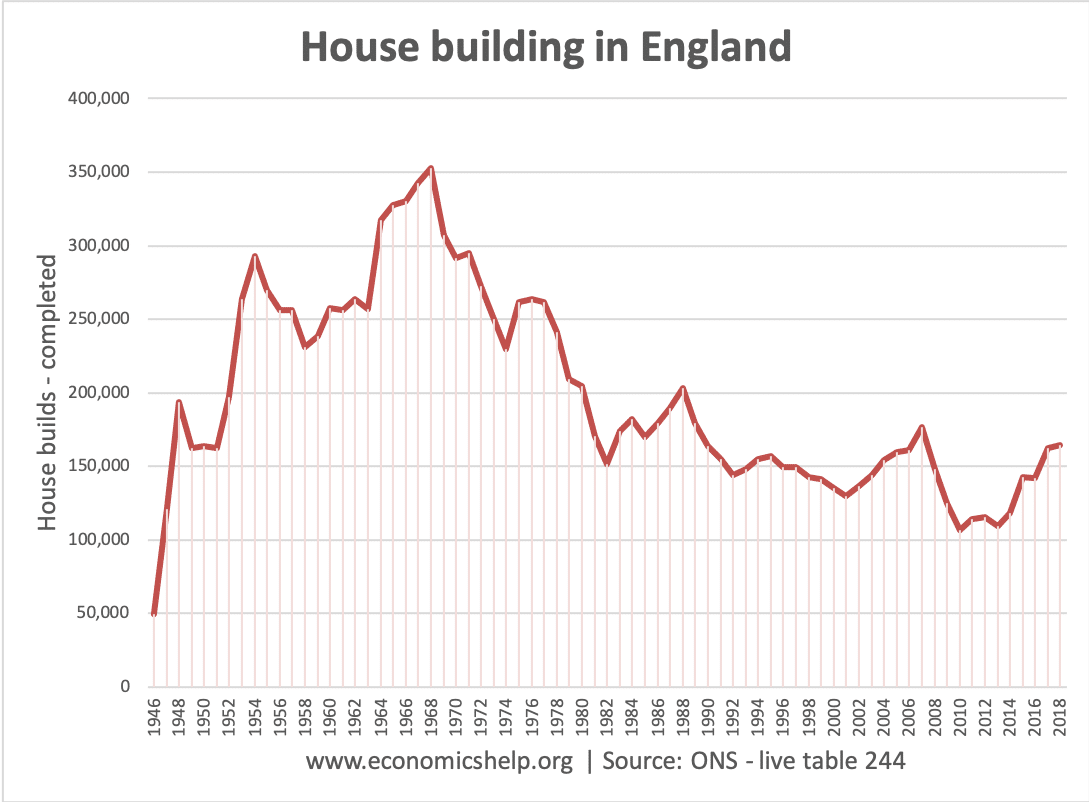

5. Decline in Social Building

Relying on the private sector to build houses has never really worked for the UK. The golden age of homebuilding was the 1960s-70s, where half of new builds were funded by council building. The mass scale of building, enabled lower costs and economies of scale. But, since the late 1970s, this social side of building has all but stopped. Not only that but there has been a net sale of council properties under right to buy. Often at a discount to market prices, councils never really invested the sales money in building new properties. So even as demand for social housing soared, supply fell, pushing more into the private rented sector.

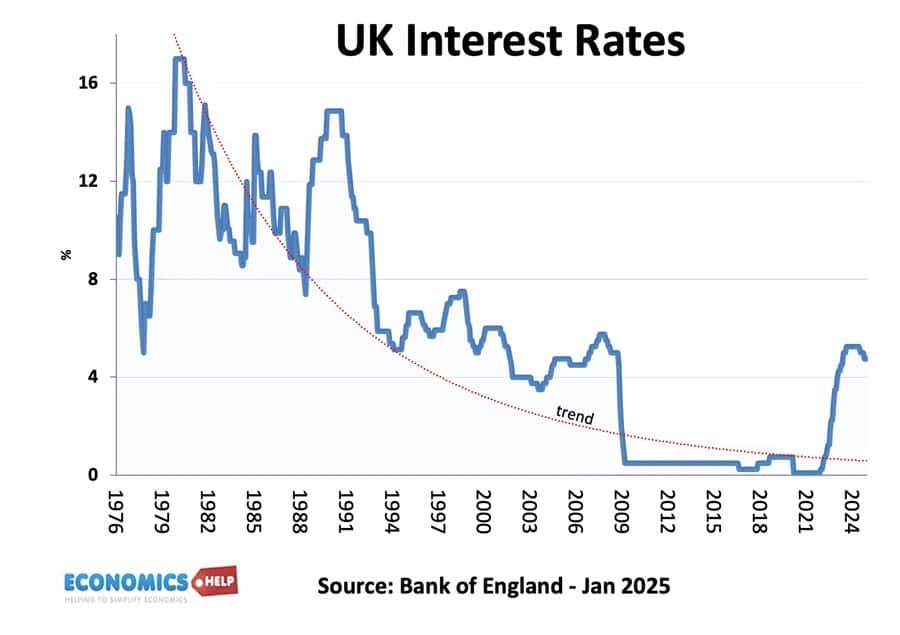

6. Lower Interest Rates

Another big factor behind housing demand is the availability and cost of mortgages. In 1992, interest rates reached a peak of 15%. The housing market crashed, repossessions soared, and prices fell for several years. But, since that period, interest rates have been on a mostly downward trend compared to the post-war period. The market was supercharged by the ultra-low rates of the 2010s. With mortgage rates as low as 2%, no wonder prices rose, despite a stagnant economy. For 2025, the likelihood is interest rates will become somewhat lower. With growth stagnant, it is hard to see any medium term rise in interest rates which would significantly reduce mortgage demand.

7. Mortgage Liberalisation

As well as lower interest rates the mortgage market was liberalised in the 1980s, giving prospective buyers more opportunity to take out bigger mortgages. Despite post-credit crunch reforms, we are seeing longer-mortgage terms, and even mortgages six times income. This increase in mortgage credit has been helped with government policy often looking favourably on home buyers. Even now, with first time buyers priced out, the government is looking at the short-term solution of making mortgages easier to get, allowing banks to lend more at higher income multiples. When governments realise they can’t address long-term affordability, short-term gimmicks like help to buy, and looser mortgage regulation is like a sticking plaster solution. It’s the dead donkey idea which just won’t go away. It makes it easier for some to buy but just pushes up asset prices further.

8. Inherited Wealth

One mystery of the housing market is why has the house price to income ratio increased so much. Surely that is unsustainable and sometimes prices must return to previous income multiples? But, one important factor in the housing market, is that it is a mistake to only look at income. Increasingly, we are using wealth, inherited wealth and gifts from parents to help buy. In other words, the rise in house prices is causing a circular effect where rising house prices leads to more wealth and this wealth is then reinvested into new housing purchases, pushing up income multiples. Last year the Bank of Mum and Dad gave £10bn to help fund house purchases. This is why many young people with high salaries are left scratching their heads thinking how can their contemporaries buy a house in London when they are struggling just to pay rent. The reason is their contemporaries are getting help from family members. Never before has parental wealth played such an important role in determining whether young people buy. Another factor why house prices to income multiples rise, is that it is more likely to have a joint mortgage application two salaries rather than one.

9. Foreign Investment

Also, when we talk about wealth pushing up prices. Foreign investment in UK property is a key factor, especially in London. Hamptons state 45% of homes in Central London were bought by an interenational buyer. Research by Dr Filipa Sa claims without foreign investment in the housing market, prices could be 19% lower than they are now. After a boom in the 70s and 80s, homeownership rates have started to tail off. If you measure share of adults, the rate is just 55%. According to OECD UK homeownership rates are one of lowest.

10. Cost of Building

Another factor in high house prices is the reported cost of building houses. Inflation and new environmental legislation has seen the cost of building a house increase significantly. Persimmon claim that the average cost of building a house is £201,000, with £55,000 profit. The cost of building a house does depend on the type and this raises another issue for the UK housing market, a reluctance to build and buy higher density high rise apartment buildings. Unfortunately, in the UK high rise flats are mostly associated with problematic tower blocks of the 1960s, associated with vandalism and crime. Many have been knocked down, but if you look at European and American cities, apartments are viewed very differently and can be a major solution to increasing supply at a relatively low cost in areas where they are needed.

What’s the outlook for house prices in 2025. Will lower interest rates lead to even higher prices? This video looks at the prospects.

https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/three-reasons-homes-in-england-are-unaffordable/