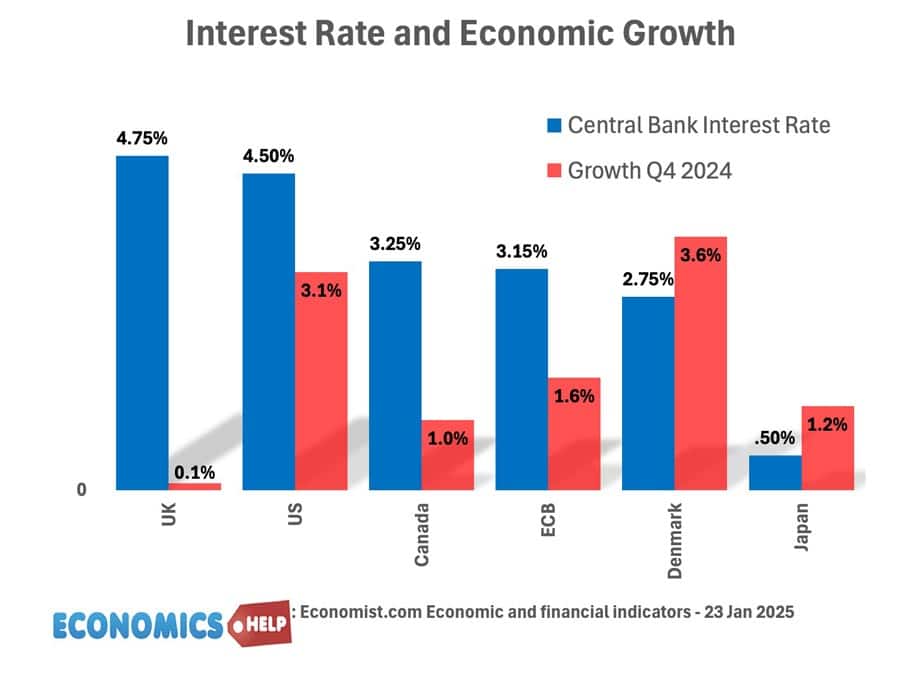

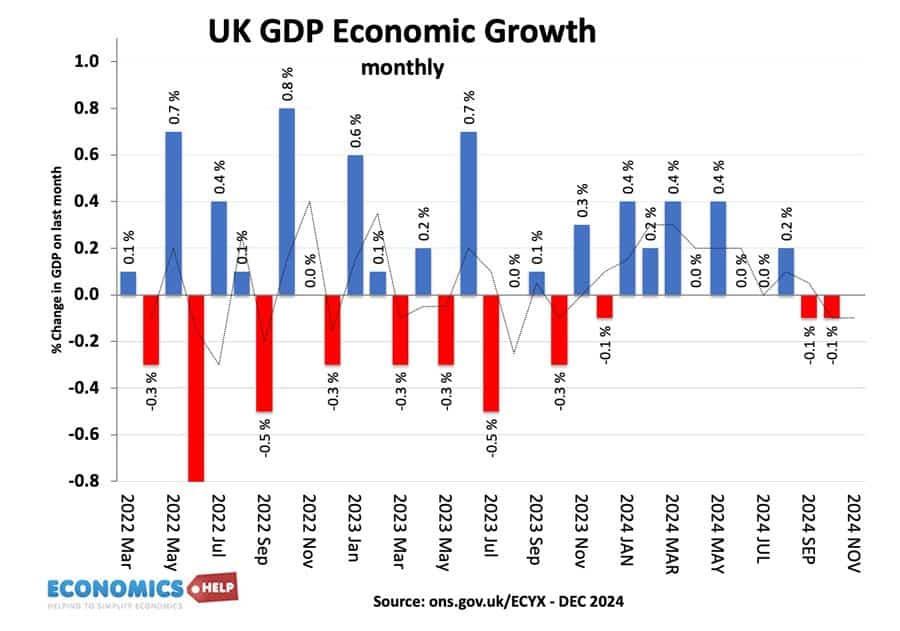

In the last quarter of 2024, the UK had the lowest rate of economic growth amongst advanced economies. Yet it also had the highest Central Bank interest rate. 4.75%. It is higher even than the Federal Reserve, despite US growth being almost double the UK in recent years.

After being caught out by the inflation surge of 2022, the Bank of England has been nursing its wounds – very keen to restore its inflation credibility. But, is it placing too much emphasis on an inflation target, when the economy faces much bigger problems of perennially low growth, low investment and a worrying rise in unemployment?

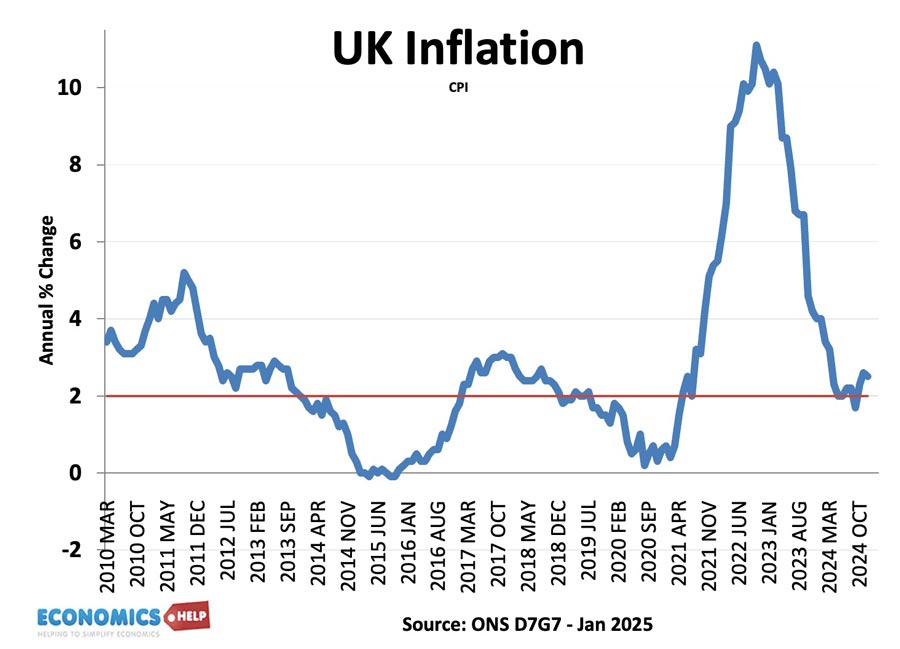

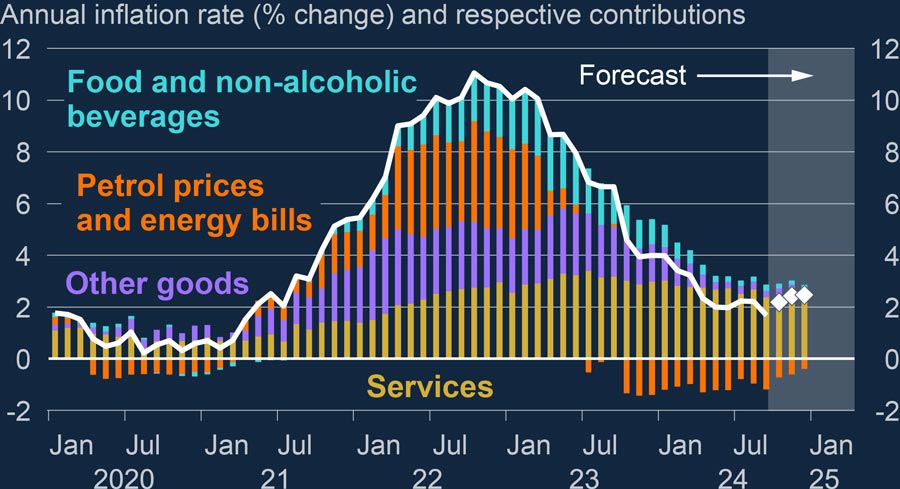

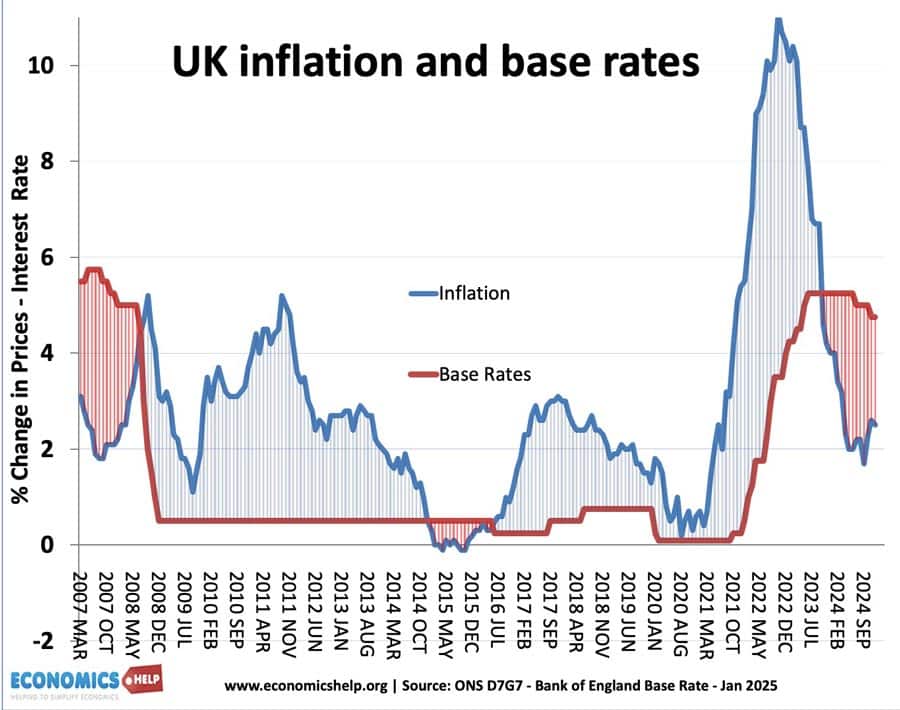

Firstly, the news on inflation is relatively good. After peaking at over 10%, the headline inflation rate has fallen to 2.5%, which is within the government’s target of 2% plus or minus one.

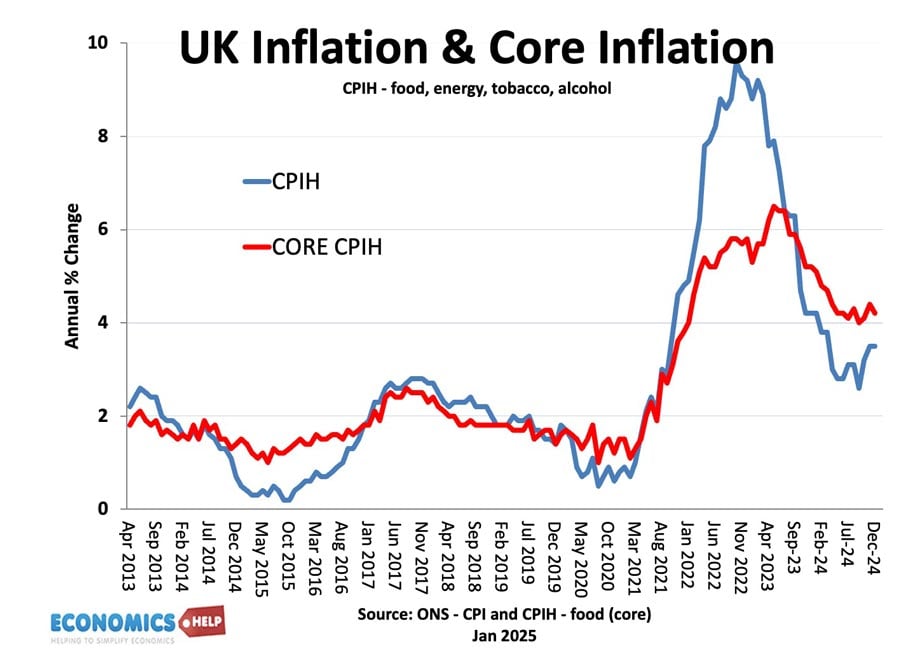

Now inflation hawks may point out that core inflation and underlying inflation are being more sticky downwards. Core CPI which excludes volatile factors is still just over 4%.

But, the important thing is the trend of all types of inflation is on a downward path. And this is hardly surprising. If the economy is very weak, if consumers are saving and firms are reluctant to invest, the economy will not be attracting inflationary pressures. The time to raise interest rates is when the economy is booming, spending is rising and firms are struggling to keep up with demand. But that scenario doesn’t reflect the UK economy. Forecasts for inflation are mostly to continue to fall throughout 2025.

Keeping interest rates at this level are counter-productive, and doing more harm than good.

Negative Real Interest Rates

Throughout the 2010s, the UK got used to a period of negative real interest rates. This means that the inflation rate was higher than the actual interest rate. But, since 2022, the UK has seen a sharp drop in inflation, and this means that the real interest rate has risen to the highest level since 2007. This unexpectedly high real interest rate acts as a brake on investment and consumption. The UK already has the lowest rate of investment in the G7 and has done for many years. High interest rates have also seen a surge in consumer saving to levels not seen for decades. And the high real interest rates are definitely one factor in encouraging people to save and not spend. But, at the moment, the economy is unbalanced and struggling firms could do with some of this saving being spent. Some might say it is good interest rates go back to normal levels. But, how do we know what normal levels are? Ageing population and lower growth has caused long-term interest rates to be falling. In fact interest rates have been on a downward trend for the past 800 years.

Will Lower Interest Rates Solve Low Growth?

Now, it is a fair point to say would lower interest rates really solve the UK’s low growth rate? I recently asked a poll about who was to blame for the UK’s current low growth. My viewers, by a large majority went for the previous Conservative government. And I don’t disagree with the wisdom of my viewers. The state of the economy for better or worse, is very much the combination of the past 10-15 years of major governmentand business decisions. Austerity, Brexit, policy u-turns, short-termism and incompetence have all contributed to low investment and low economic growth. However, at least as far as short-term demand in the economy, the Bank of England have more influence than the government. Not only are the Bank of England keeping interest rates high, but they have aggressively reversed quantitative easing, selling bonds onto the market. Meaning the gilt market will have to soak up £300nm of gilts this year – no wonder, the UK has the highest bond yields. So the economy could be helped by a looser monetary policy, more suitable for the state of the economy.

Lower Rates No Panacea

However, lower interest rates are definitely not a panacea. If the underlying structure of the economy is weak, if investment is low, taxes rising, firms uncertain, then the long-run trend rate of growth will be lower. The big concern for UK economy is that the trend rate of productivity growth has fallen in the past 15 years. You can’t fix that, just by cutting interest rates. Though, if you want to boost productivity and the supply side of the economy, you need at least a growing economy to encourage investment. Pushing the economy into recession through tight monetary policy will just make it harder.

Budget Effects

But, isn’t the government’s budget inflationary? Are we at risk of stagflation? Won’t higher pay lead to inflationary pressures? It is true, that one of the current strengths of the UK economy is the rise in real wages. We are seeing the largest rise in real wages for many years. It might suggest the economy is not quite as bad as some people make out. But, for the pessimists this rise in wages will just cause more inflation. I’m not convinced by this argument. Firstly, to talk about a wage-price spiral in the UK economy is absurd given the current economic weakness and stagnation. Secondly, a lot of real wage growth is a lagged effect of workers catching up from past real wage falls. Thirdly, the budget does include higher government spending, but it also includes higher taxes, which will dampen demand. The net effect will be mildly expansionary, but it’s not like say the Lawson budget of 1988, which caused a massive economic boom and later inflation.

In fact, there are greater noises about the negative effect of the budget on jobs and employment. The CBI claim that many firms are planning to cut back on employment as a result of higher national insurance contributions. There may be an element of business exagerrating the worse case scenarios to campaign for lower taxes. But, there is no doubt, that there are tentative signs of rising unemployment and firms looking to cut labour costs at a time of higher wages and higher taxes. Given this increase in costs, lower interest rates would be important for firms who face high borrowing costs.

What Should Bank of England’s Job Be?

A good question is what should be the Bank of England’s remit. What’s their job? If you are rigid about the government’s inflation target of 2%, you can understand why the Bank have been slow to cut interest rates. If low inflation is the only thing that matters, you want to prove to markets you can bring inflation down. But, there are a few points. Firstly, where did this magic 2% inflation target come from? The answer is that it was rather arbitrary, it didn’t come from an academic study about optimal inflation rates. It was actually New Zealand Central Bank the first to target inflation came up with 2% and everyone followed suit. You could make a good argument that the inflation target should actually be 2.5% or even 3%. High inflation can be devastating, we saw that in 2022. But, the other unwelcome truth is that when you get this kind of cost-push inflation shock of 2022, interest rates are pretty useless at solving it. You can’t stop rising oil and gas prices, by higher interest rates. Higher interest rates are useful if the economy is booming, but the UK economy definitely isn’t booming. Back in 2010, the UK had an inflation shock, inflation rose to 5%, but the Bank kept interest rates at 0.5%. It knew inflation would come down on its own and it knew higher interest rates would just further reduce growth.

Limits of Monetary Policy

In defence of the Bank of England, interest rates and quantitative easing are a limited tool for solving economic problems. For example, if we were only concerned about the housing market, then I would say there is a good case to keep interest rates where they are. Cutting interest rates risks another increase in housing demand and house prices, at a time, when it would be better to prevent further rises. But, you can’t expect the Bank to sacrifice goals like the economy and unemployment, just to try fix the housing market. The Housing market can’t really be in remit of Bank of England. You can’t target everything by just one tool.

If the government want to target economic growth, redefining the goals of the Bank of England could involve giving equal weighting to promoting sustainable economic growth as well as low inflation.

What about the impact on inflation expectations and the credibility of the Bank of England. When inflation rose to 10% in 2022, the Bank were harshly criticised for having failed. It made the quantitative easing of 2020 look particularly unnecessary and damaging. But, as a result of this, they are determined to regain credibility. But, this is misplaced. Firstly, inflation rose to 10% in pretty much every advanced economy. The only way to really prevent that kind of inflation was through a massive government intervention in energy markets like Spain and France did to some extent. If they are concerned about credibility they should be aware they risk uncessarily slowing the economy.

Related