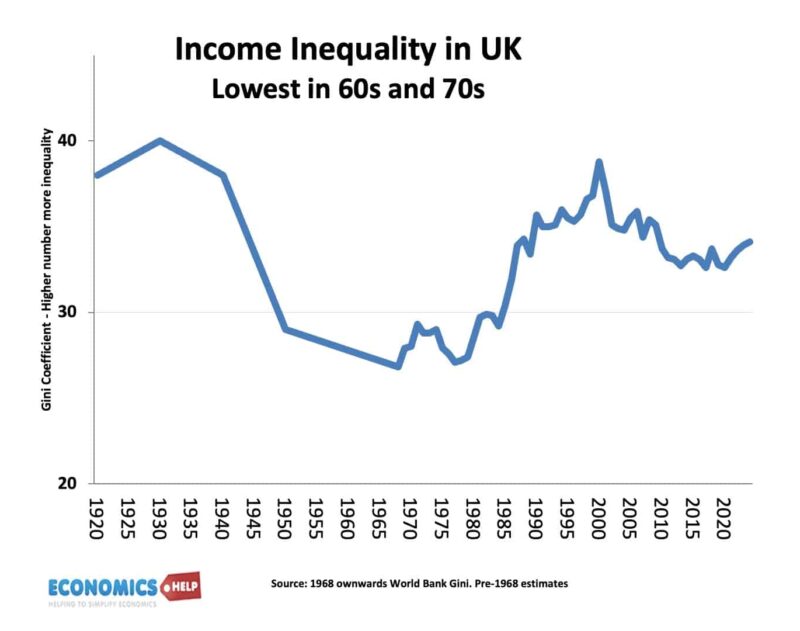

Rubbish piled on the streets, record levels of strikes, an IMF bailout and runaway inflation. The 1970s has gone down in the popular imagination as a dark time, literally in the case of the 3-day week, when lights were turned off, but also in terms of growing violence, a break in the post-war social contract and an economy losing its grip. Rather like today, there was a flood of pessimistic literature, “The Politics of Economic Decline, Britain: Progress and Decline. And most evocatively, “Is Britain Dying”. It seems you didn’t need YouTube for shrill titles of economic apocalypse. But when you think of the 1970s, what actually comes to mind? Saturday Night Fever, Punk Rock, Abba or is it just psychedelic brown wallpapers and Raleigh Choppers? Beyond the myths of the 1970s, it wasn’t all bad; ironically, the decade had some of the fastest growth in real wages in the entire twentieth century. Living standards improved, housing was affordable, and it was close to the UK’s peak moment of equality in terms of incomes and wealth.

Yet, even the most revisionist view of the 1970s, can’t deny it was a period of economic turmoil, with a rise in the misery index and relative decline. Not for nothing was the UK called the sick man of Europe. The post-war consensus was broken.

1970s

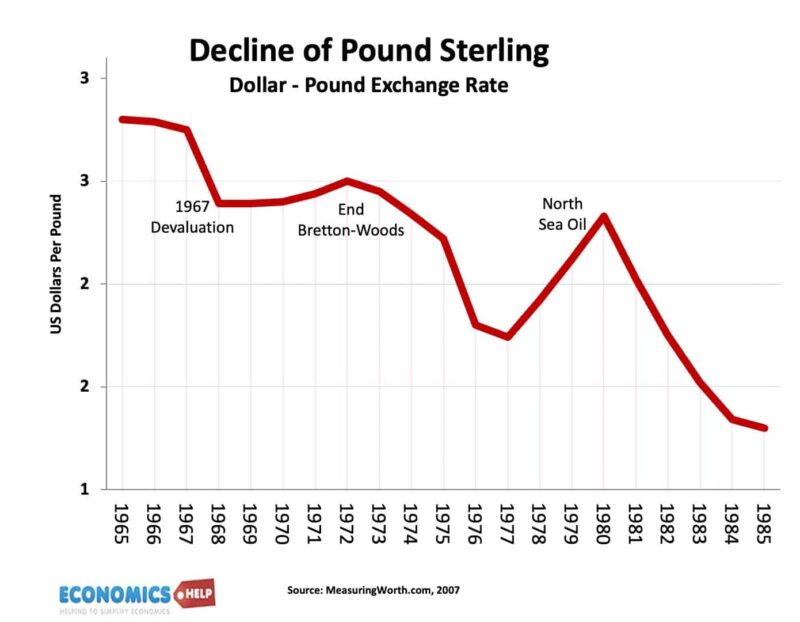

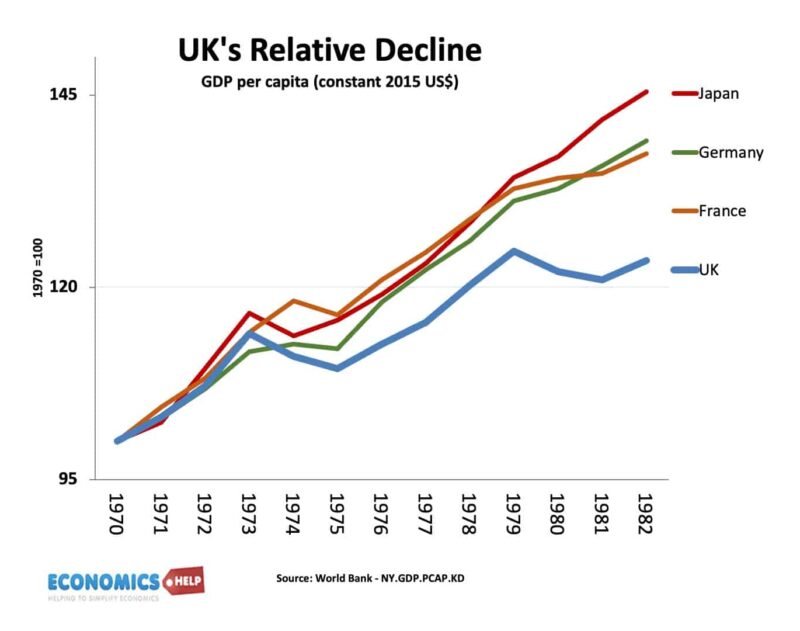

Since 1945, the UK economy had attained strong economic growth, near full employment, relatively low inflation and was successfully expanded the NHS and welfare state. But, despite this rise in living standards, it masked a relative long-term decline in UK competitiveness. In 1967, the Pound was forced to devalue, making imports more expensive. But, even this devaluation couldn’t restore the fortunes of UK industry, which needed more devaluations throught the 1970s. UK industry was bedevilled by several problems. The UK was still a class-ridden society with the management and workers living in different worlds. In the 70s Trade Unions were at the peak of their power, with union shop stewards like Red Robbo gaining national prominence, after leading 523 strikes at British Leyland in 30 months. The number of days lost to strikes was hitting record levels, and this was a factor in reducing UK productivity and competitiveness. The media loved to highlight stories such as night shift workers taking a sleeping bag to work, so they could sleep through their shift. But, it wasn’t just militant workers – poor management, lack of investment, out-of-date education and a culture of complacency led to the UK falling behind. In the 1970s, memories of the Second World War and the British Empire were still strong in the national psyche.

But, if the UK won the second world war, it was the Germans and Japanese who were winning the post-war economic race. Germany, France and Japan were booming, the UK was falling behind. The UK car, industry, once the largest exporter in the world was churning out the notoriously unreliable Austin Allegro and Morris Marina, no wonder the UK had a growing trade deficit.

Barber Boom

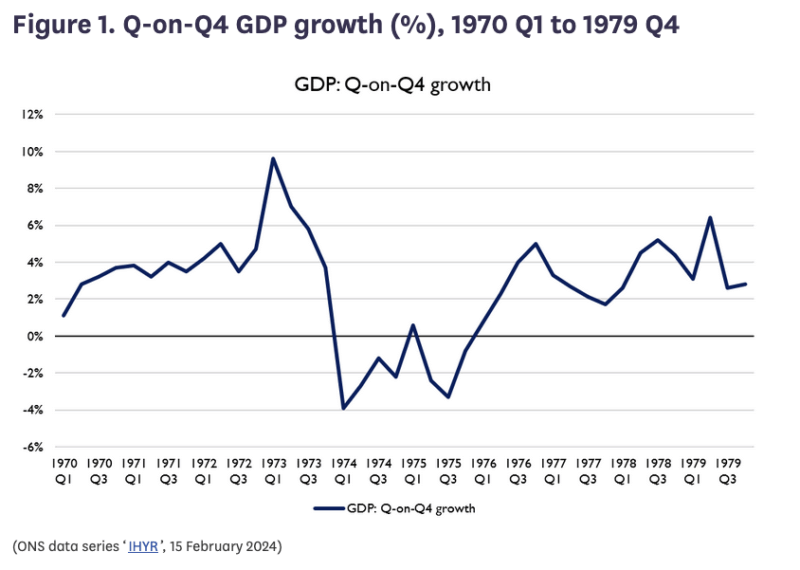

In 1970, Edward Heath’s government had been elected on a manifesto of reducing government intervention in the economy. But with unemployment rising above 1 million for the first time since the Great Depression, the government u-turned and pursued ambitious tax cuts and higher spending, a return to the post-war economic orthodoxy. There was a boom in economic growth, fueled by a relaxation of bank regulations on lending, which caused the money supply to rise. By, the end of 1972, the barber boom caused economic growth of a scarcely credible 10%. Yet, the economy couldn’t keep up with the demand, inflation rose, and unions demanded wage rises to keep up. In 1972, the NUM, under the leadership of a young firebrand from South Yorkshire, Arthur Scargill, went on strike for higher pay – a mass picket at Saltley Gate in Birmingham threatened to cut off the nation’s power, and so the government coal board agreed a 27% pay rise. At that time, 80% of Britains’ electricity came from a combination of coal and oil, and coal miners who still at the heart of the UK economy. But the inflation-busting rise for miners was not welcomed by all – a young Conservative MP, Margaret Thatcher, never forgot the Heath government’s u-turns on economic policy and the apparent capitulation to striking miners.

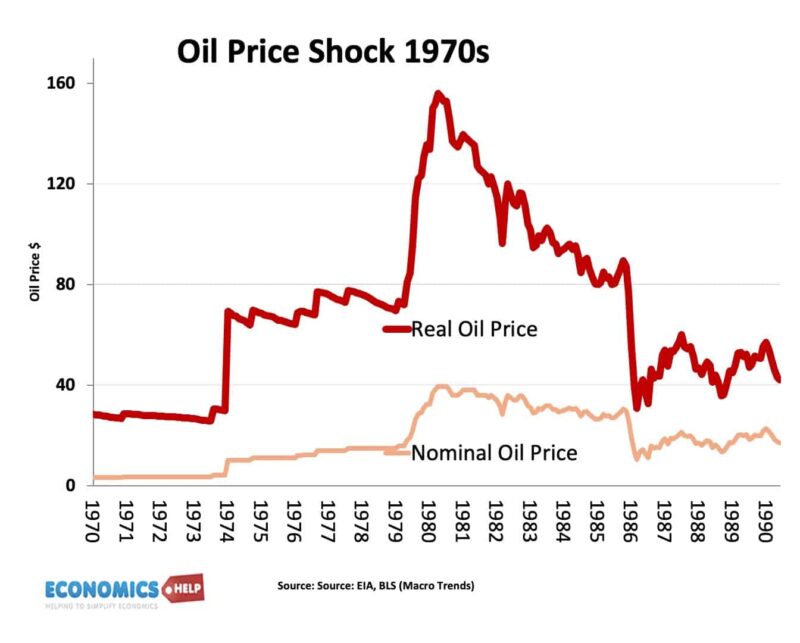

But, the post-war economic boom was well and truly burst by events halfway around the world. The 1973 Yom Kippur War saw OPEC countries flexing their muscles and restricting the supply of oil. Oil prices tripled, causing a rise in inflation around the world. In response to inflation, Interest rates were increased to eye-watering levels at a time of falling returns on investment. The boom turned into a spectacular bust. At the start of 1974, the National Union of mine workers went on strike again. With oil rationed and coal miners on strike, the Conservative government imposed a three-day week to save power. The lights literally went out, Britain’s two main tv channels BBC and ITV had to cease broadcasting at 10.30pm. Industry could only work three days a week. Trying to build support based on antipathy towards unions, the Conservatives called an election with the slogan “Who Governs?” But the electorate returned the response not you, Mr Heath and it was Labour who formed a minority government. By October, a second election was held, which Labour very narrowly won, but with the economic outlook darkening, a wafer-thin majority, proved a mixed blessing.

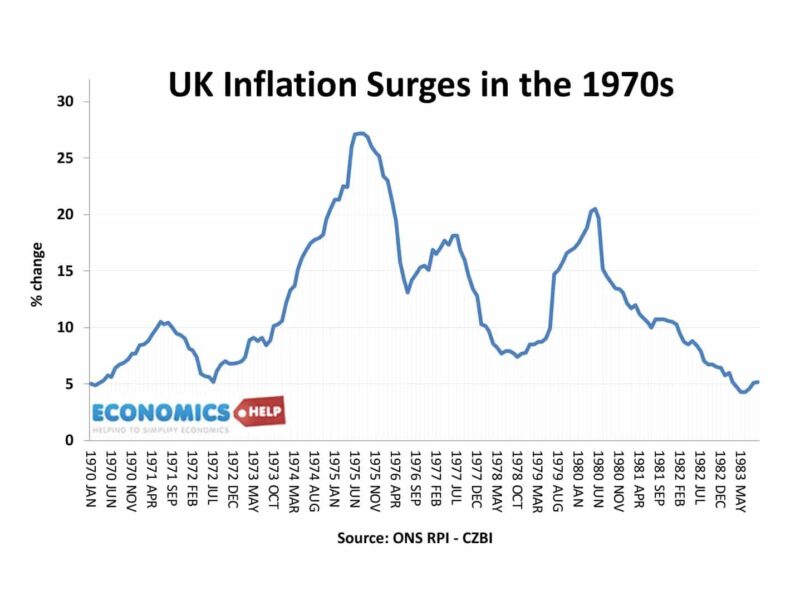

Inflation

Despite promising an incomes policy and contract with the unions, inflation continued to soar in the mid 1970s to a record breaking 25%, the highest level since the Napoleonic Wars. Combined with a trade deficit and high government borrowing, Sterling continued to slide. In 1976, the UK had to approach the IMF for a bailout. They received $3.9 bn, but on the condition on $2bn spending cuts and higher interest rates. Once an economic super-power, the UK was first advanced country to need a bailout.

Winter of Discontent

Actually, the crisis was not as bad as first feared. The Treasury had made overly pessimistic forecasts. Government debt was still on a general downward trend – half the level of today. Oil revenues were starting to come on tap, a big boon to the balance of payments. In fact, it seemed the Labour Party’s income policies were working in bringing down inflation. But, in 1979, a severe winter and efforts to limit pay rise to just 5% caused a further wave of strikes across the country. There were fears of fuel and food shortages, often exaggerated by the media, but at the same time, the very visible sight of rubbish piling up was highly evocative. It also led to the first ever strike by gravediggers in Liverpool. Although they striked for only two weeks in one city Liverpool, media reports of dead bodies piling up became emblematic of the era, which seemed characterised by decay, decline and inflation. 1979 was a record year for strikes 4.5 million people were involved, 29.5 million working days lost. Something was broken. “Labour is not working” was one of the most successful political ad campaigns of all time. Even the Labour PM Jim Callaghan was depressed at the intransigence and militancy of the unions. But, it didn’t help when returning to Britain, he asked “Crisis, what crisis”? The upcoming winter of discontent led to a big swing from Labour to the first women to lead a British political party. Margaret Thatcher promised tax cuts, monetarism, lower borrowing and reducing union power. Few could anticipate what her legacy would actually be.

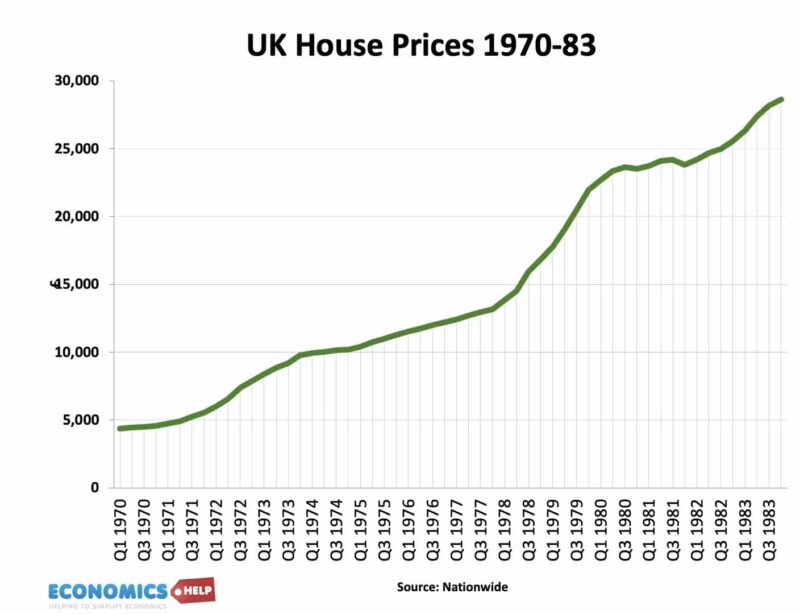

But, whilst the 3-day week, strikes and piles of rubbish make powerful images, it was far from the full story of the 1970s. During the 1970s, House prices rose 400% from £4,378 to £22,000. Partly, this was hedging against inflation, but also due to the deregulation of mortgage lending, which saw more people able to buy a house. Home ownership rates rose considerably. Yet, despite the boom in house prices, they remained affordable around 3.5 to 4 times income. A far cry from today’s prices. In the 1970s, the UK was still building high levels of council homes and councils were even able to increase their housing stock by buying property from the private sector relatively cheaply.

For all the talk of inflation and economic blackouts, the bigger picture of the 1970s, is that real incomes increased, the number of foreign holidays doubled from 4.5 million to 8.4 million. It was bad news for old fashioned British resorts like Morecambe and Blackpool, but Brits now had a taste and ability to pay for the package holiday, with Spain, France and Italy, popular destinations.

The rising incomes also contributed to a mini consumer boom, with the growth in supermarkets, convenience food like Chicken Kievs and the first Walkmans and video cassette recorders. And don’t forget Star Wars released in 1978. In fact if you ask anyone about their childhood in the 1970s, one thing they remark on is much greater freedom, get on your Raleigh chopper and roam the streets, which weren’t completely congested.

Darker Side of the 1970s

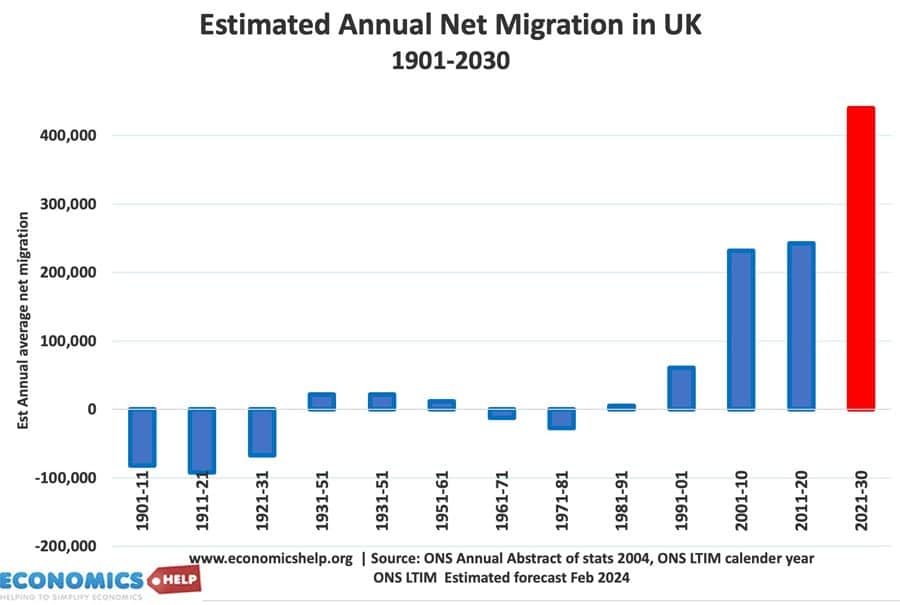

Yet, there was an undeniable darker side to the 1970s, Enoch Powell’s Rivers of Blood speech in 1968 had split the nation, there was widespread overt racism, and the National Front were a menacing, if somewhat limited, political force. Ironically, the 1970s, was a decade of net zero immigration, with more people emigrating than immigrating. Many felt Commonwealth countries like Australia and Canada had more opportunities than tired old Britain.

The most difficult aspect of the 1970s was the sectarian troubles in Northern Ireland. Bloody Sunday in Derry and IRA bombings in England was a painful backdrop to the decade of rising sectarian conflict. Whilst the Second World War had created a unifying effect, by the 1970s, there was the rise of Celtic nationalism, with the Scottish National Party making important breakthroughs. The old certainties of what the UK was were starting to fray.

EEC

Whilst some hankered after the old Empire, and others looked to devolution, another seismic shift was the UK’s entry into the EEC in 1973. Touted as a solution to the UK’s economic woes, the main critics were a few like Enoch Powell on the right, but mostly the hard left under the likes of Tony Benn who claimed the EEC was a capitalist club which would take away sovereignty. Two years after joining the PM Harold Wilson held a referendum on the question of the EEC. Only 32% voted no, 67% yes, a clear answer to the constitutional change. What nobody really foresaw is how Europe would become such a divisive question a few decades later.

How did the 1970s change Britain? Inflation and relative decline spelt an end to the so called post-war Keynesian economic consensus. To many the power of the unions had become uncomfortably high, tax rates were too high, and the UK needed radical reform.

Even in 1976, the Labour chancellor Denis Healy was adopting monetary targets and claiming credit for slower growth in the money supply than under last Conservative government. But, it was Mrs Thatcher and adherents of Milton Friedman who would make it a more ideological approach

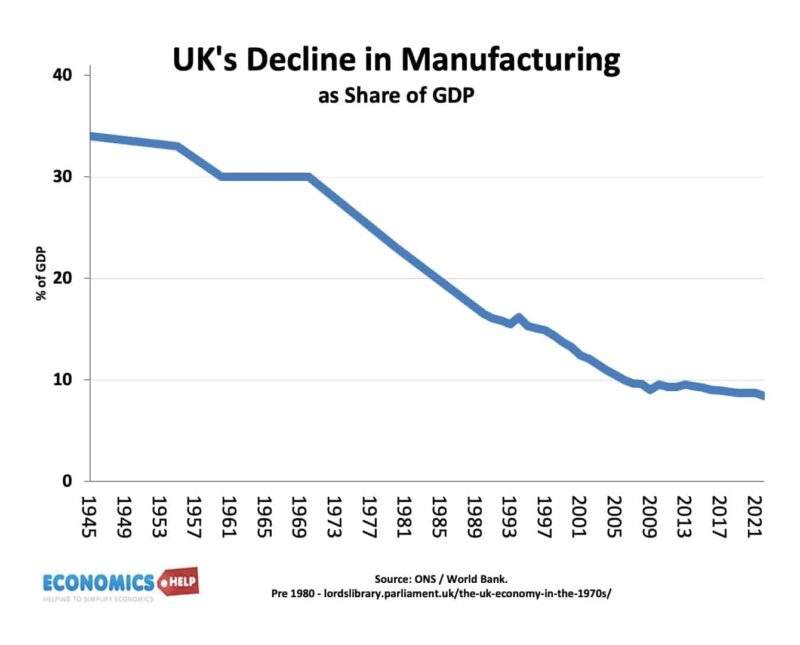

The mass strikes of the 1970s marked a turning point in industrial relations and UK manufacturing. The UK was the first country to industrialise and the first country to deindustrialise. In 1970 manufacturing was 30% of GDP. By 1980 it was 23%, but this decline in manufacturing was just the start. It would hallow out former manufacturing regions in the decade to come.

Concorde

It wasn’t all decline. In 1976, Concorde entered service, the first commercial supersonic plane was a great technological achievement of British and French engineers, but despite achieving iconic status, it was a commercial flop, never recovering the millions of government investment. Like Britain in the post-war period, it flattered to deceive. The UK was still building things in the 1970s. Roads everywhere, like Spaghetti Junction in Birmingham and really ugly buildings. Prince Charles quipped the architects of the era were more destructive to the city’s skyline than the Luftwaffe. He did have a point.

Whilst the three day week and winter of discontent created powerful images exploited by a critical media, underneath, the apocalyptic predictions of the UK’s demise were also overblown. For many people, life actually continued to get better in the 1970s. The three day week lasted just two months. A more enduring impact of the 1970s was rising home ownership, rising car ownership and a rise in the number of foreign holidays. The UK was also great at building ugly road infrastructure. opened in 1972 a symbol of the roads dominance.

Never the Same

But, whatever your view of the 1970s, it did break or start to unwind many aspects of British economic and political life. There would never be the same consensus on the economy, unions or the welfare state. Despite the success of Queen Elizabeth II’s silver jubilee in 1977, the UK was starting to fracture, Celtic Nationalism, the troubles in Northern Ireland a hesitant embrace of Europe. The political consensus was also split. In the late 1960s, Conservative MPs may well have believed in high tax on the rich, a welfare state and the necessity of full employment, that would become a rare breed in the coming years. The 1970s, also split the Labour party, with the right wing furious with the Union militance and the increasingly radical left, under the direction of Tony Benn, Micheal Foot and Marxist infiltration furious with what they saw as the Labour government’s betrayal of the working class and socialist ideals. In the 1979 Richard Dimbleby lecture, Roy Jenkins president of the EEC quoted W.B. Yeats “The Centre cannot hold. The best lack all conviction and the worst are full of passionate intensity.”

Perhaps some things don’t change. But, one undoubted impact of the 1970s, is that it set up the stage very nicely for Mrs Thatcher to unleash her free market revolution on Britain, the UK would never be the same again. So did Thatcher save or break Britain further, this video goes into more detail.

Related

Sources

- Aronline.co.uk/archive/sleeping-on-the-job-essay/

- 1970s – Medium

- https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/the-uk-economy-in-the-1970s/

- https://journals.openedition.org/rfcb/1662

- https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2008/dec/30/archives-callaghan-labour-memo-1978

- https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MSBMUKA

- Politics of the 1970s