Definition of deindustrialization

Deindustrialisation involves a decrease in the relative size and importance of the industrial sector in an economy. It may involve a decrease in the absolute size of industry or it might just mean that manufacturing/industry takes a smaller share of GDP and employs a smaller % of the workforce.

Deindustrialisation will invariably involve an increase in the importance of the service sector to take the place of industry.

Reasons for deindustrialisation

Services are a luxury good. As incomes rise, people can afford more personal services, which have a higher income elasticity of demand. If your income rises to £20,000 you can buy a car (manufacturing sector), but if your income rises by even more, you may be able to afford more taxi rides (services) or even employ a chauffeur. Since 1945, western economies have generally seen a significant rise in real incomes due to positive economic growth. This has led to growing service sector industries, such as tourism, cafes, retail and also financial services like pensions. As a result, spending on manufactured products has fallen as a % of total GDP, instead, we spend relatively more on services.

Shifting comparative advantage. Manufacturing goods tend to be quite labour intensive. Rising labour costs in advanced industrial countries mean that there is a long-term shift in comparative advantage. It becomes relatively cheaper to import these manufactured goods from low-cost labour producers in S.E. Asia/Central America. In recent years, the UK has lost comparative advantage in industries, such as clothing, electrical manufacturing and developed a comparative advantage in financial services. Multinationals have often outsourced production from advanced economies to emerging economies with lower labour costs.

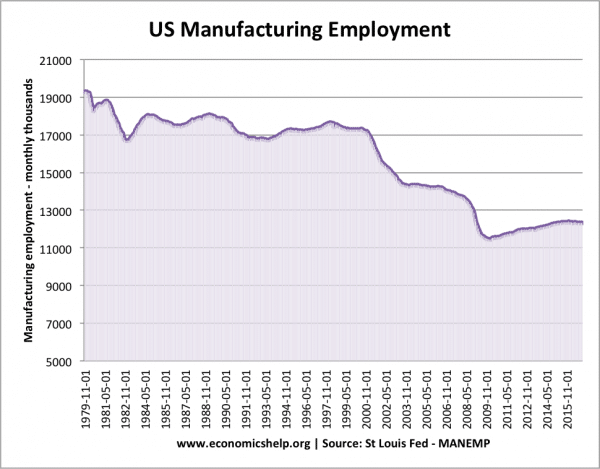

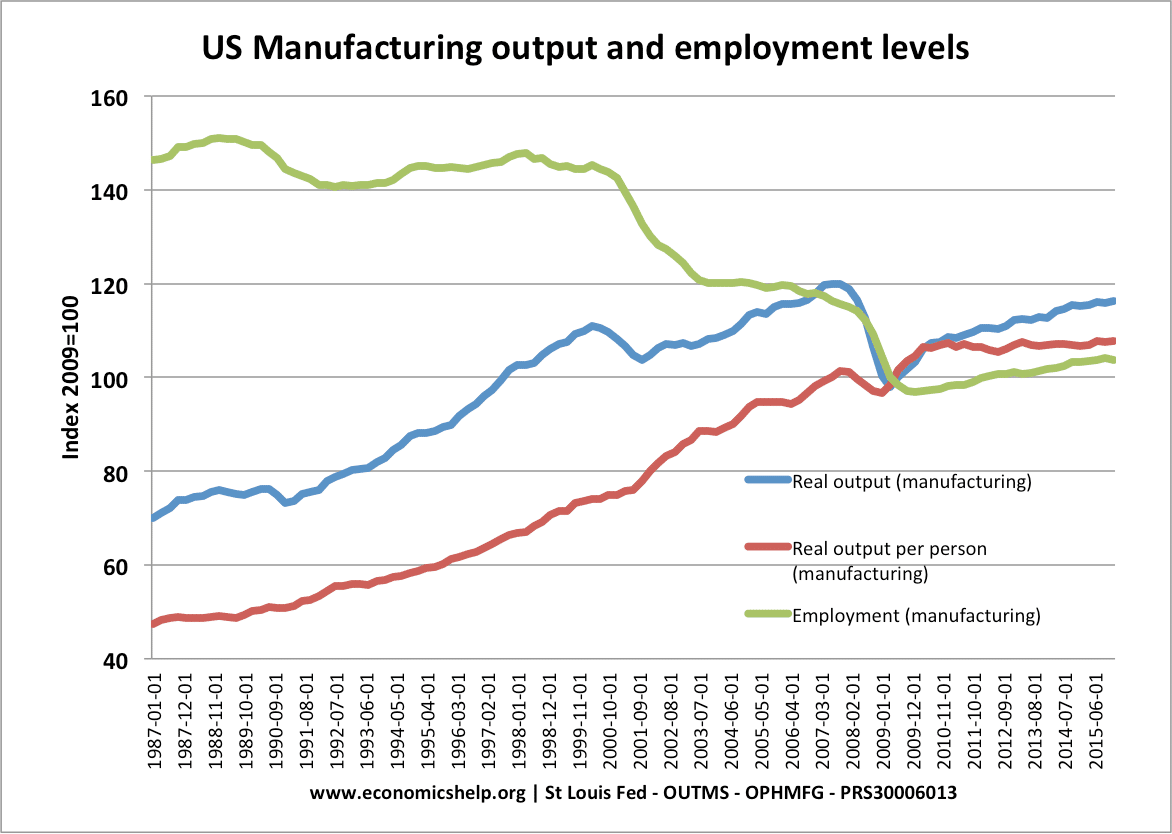

Increased labour productivity in manufacturing. Manufacturing tends to enable higher growth in labour productivity than the service sector. Therefore as technology develops, the number of workers required for manufacturing falls compared to the service sector. For example, since 1979, the US has seen a rise in the absolute volume of manufacturing output, but employment has fallen from 19 million to 12 million.

Short-term shocks. In the case of the UK, the 1981 recession led to a sharp fall in manufacturing output due to appreciation in the exchange rate (making exports uncompetitive), high-interest rates and depressed demand. However, the short-term fall in manufacturing output became prolonged with many former industries never recovering from this particular shock. Deindustrialisation would have occurred without this demand-side shock, but it perhaps sped up the process.

Deindustrialisation in the UK

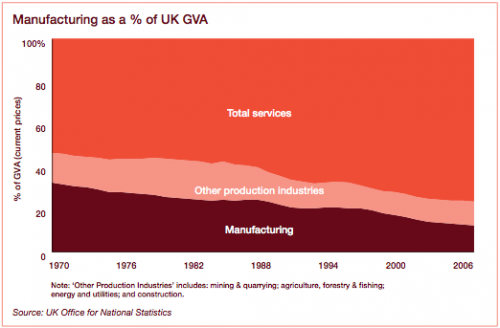

Manufacturing as a share of real GDP has fallen from 33% in 1970 to 12% in 2010.

For example, the UK has experienced a process of deindustrialisation, most notably since the early 1980s (UK Economy 1979-1984)

Costs of deindustrialisation

Structural unemployment. The process of deindustrialisation leads to job losses in certain sectors and in certain types of jobs. Although jobs are being created in the service sector, it can take time for the unemployed to switch careers. Due to geographical and occupational immobilities, people who lose jobs in manufacturing can be unemployed for a considerable time. For example, many jobs in the manufacturing sector are unskilled manual work; for an unemployed coal miner with few qualifications, it is difficult to get new work.

Feelings of alienation. Even if former manufacturing workers get new jobs in the service sector, it can still be disruptive. New jobs may be part-time, temporary, low-paid and without the sense of camaraderie that manufacturing jobs may give.

Regional decline. Deindustrialisation is often felt more acutely in particular towns and regions which relied on the manufacturing sector. For example, cities like Detroit and other areas in the ‘US rust belt‘ have struggled to reinvent themselves as the main employer of the town closes down. Overall, the national economy experiences higher real GDP, but it is not a Pareto improvement because some areas suffer capital and human flight – aggravating problems of decaying inner cities.

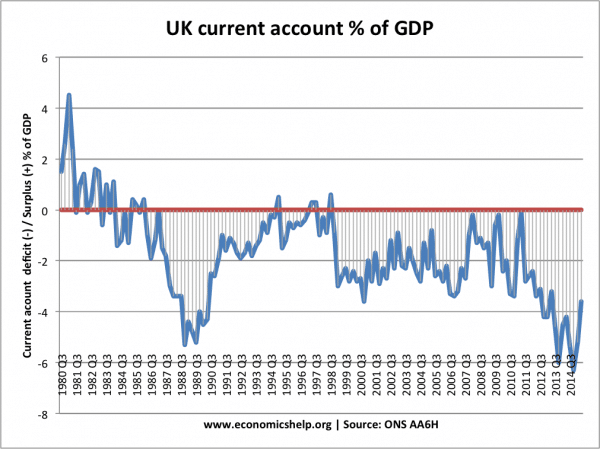

Current account deficit. Countries which have undergone deindustrialisation have often experienced a persistent current account deficit with a particular deficit in trade.

Since 1980, deindustrialisation in the UK has led to a persistent current account deficit.

Benefits of deindustrialisation

Although we tend to focus on the negative impact of deindustrialization, it can also have many benefits.

- Higher incomes. One reason for deindustrialisation is that with higher incomes householders are spending more on services. Deindustrialisation is a reflection we can afford to buy a wider range of goods and services.

- Trade increases net welfare. Importing cheaper goods from abroad enables disposable incomes to go further. It also leads to increased welfare and rising incomes in the developing world.

- Service sector job opportunities. Whilst some may miss their former manufacturing job, it is not always the case manufacturing jobs are superior in non-monetary benefit terms. Some service sector jobs can be more creative, less physically taxing and allow a greater degree of flexibility. Someone with ill health may be unable to work in manufacturing, but can work in the service sector. Also, many former manufacturing jobs, such as mining were dangerous and physically demanding – leaving miners with health problems from breathing in coal dust.

- Environmental benefits. The industrial sector often caused pollution, which damaged the environment and air pollution. Closing down mines can have positive environmental impacts. For example, this former mining area was replanted with trees – creating new jobs and also an improved environment (e.g. Planting trees in Leicestershire Guardian link)

- Capital flow. The counter-balance of a current account deficit is that the UK has seen capital inflow from China and other countries which has helped finance investment.

Deindustrialisation in the US

Deindustrialisation in the US has seen jobs in manufacturing fall from 19 million in 1979 to 12 million in 2016.

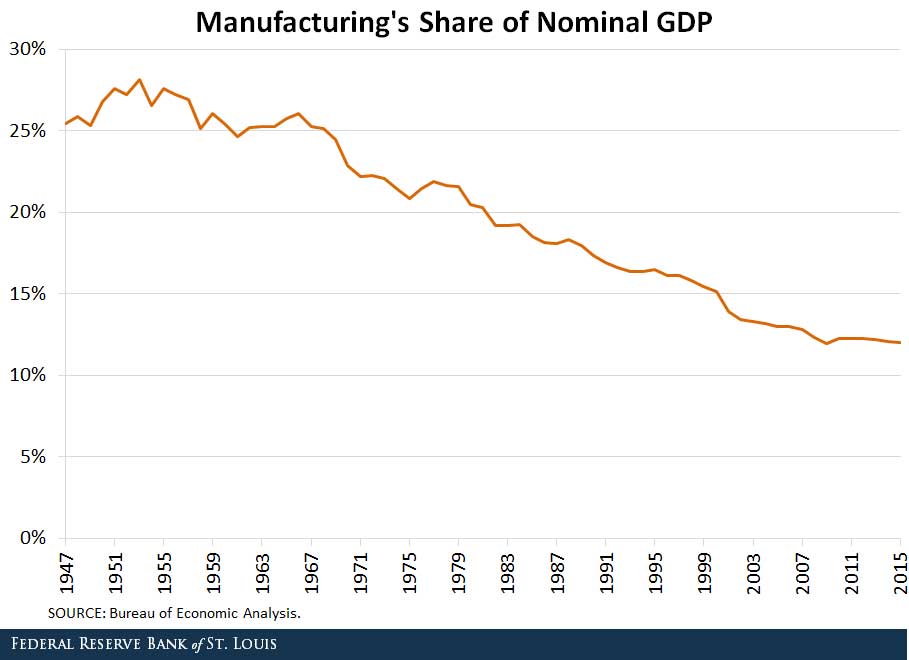

This has led to particular problems in the US rust belt, with higher levels of structural unemployment. As a percentage of GDP, US manufacturing is down on previous decades, but in absolute terms, manufacturing output has increased in the past two decades.

Since 1987 manufacturing productivity has increased significantly enabling lower levels of employment.

Manufacturing has fallen as a share of nominal GDP from 25% to 12%

Related

Service sector goods are characterised by constant returns to scale. A window cleaner is about as productive now as he was 50 years ago. Moreover most service sector jobs – with the exception of tourism, financial services and education – are not tradeable on world markets. You cannot export a haircut from London to Lahore. This means that a permanent deficit on current account becomes inevitable. This means that the Treasury has to sell bonds on global markets to raise cash to plug the shortfall of structural trade deficits. Of course these debts have to be serviced which means an outflow of capital from the UK back to the holders of UK gilts. And BTW ‘capital inflow from China’ is not a gift – it is a liability which cannot go on forever. Also the selling of national assets to assuage the deficit on current account also has its limits.

Manufacturing is not some luxury that can be tossed aside. Just ask the Germans.