Disequilibrium occurs when the markets fail to clear and find their final equilibrium point. Disequilibrium could occur if the price was below the market equilibrium price causing demand to be greater than supply, and therefore causing a shortage. Disequilibrium can occur due to factors such as government controls, non-profit maximising decisions and ‘sticky’ prices.

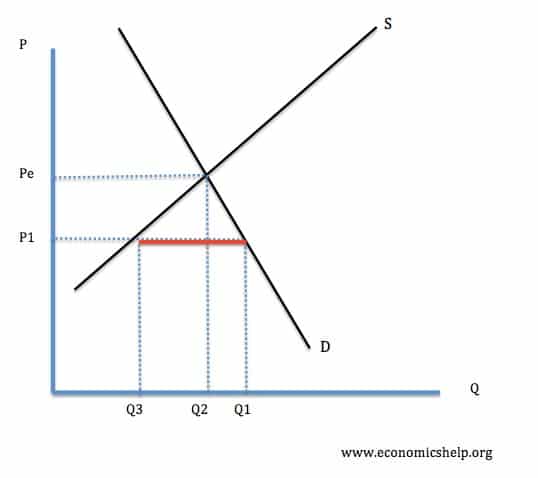

Disequilibrium due to price below equilibrium

With a price of P1, the demand (Q1) is greater than the supply (Q3). This disequilibrium will lead to a shortage (Q1-Q3) and long queues as consumers try to get the limited supply. In a free market, you would expect firms to deal with this disequilibrium by putting up the price to ration the demand.

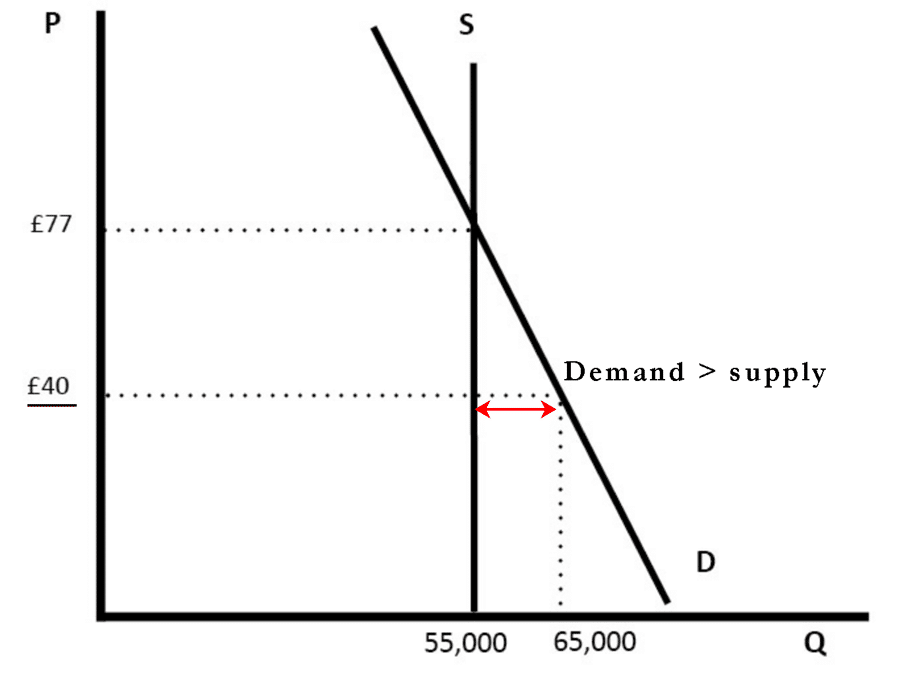

Example of disequilibrium – football

A good example could be tickets for a football stadium. With a strictly limited supply (55,000). Demand for big games may far exceed supply. The market equilibrium price would be £77. But, the football club may decide to set prices at £40. This causes 10,000 to be unable to go to the game at that price.

Football clubs are likely to avoid setting a market clearing price (£77) because they don’t want to be accused of being ‘elitist and unfair’. It is important for clubs to create good relations with the local community. Also, with sport, the profit motive is not the only factor behind the business.

Therefore, they may keep prices well below the market clearing price (£40). (where demand is greater than supply) The problem is that many fans who want to watch the game can’t get in. It may lead to a black market where some resell tickets to those willing to pay a much higher price.

There could be a disequilibrium through a maximum price. – which is a government control to set prices below the equilibrium. (e.g. renting)

What causes disequilibrium?

Why do some markets lead to disequilibrium

- Sticky prices – Firms may be committed to keeping prices the same for a whole year. Therefore, if there is a seasonal increase in demand, you get a shortage because the firm doesn’t want to keep changing prices – especially when demand is quite volatile. There are menu costs in changing prices, but also they can annoy customers by frequently putting up prices.

- Social factors – Sometimes firms may keep prices deliberately low because they feel they have a commitment to the community – e.g. landlords not increasing rent, football clubs not increasing ticket prices.

- Non-profit maximising decisions. Economics assumes that individuals are rational and seeking to maximise utility. However, in the real world, other factors are at work. For example, the taxi operator Uber uses ‘surge pricing’ – this allows the price to rise with heavy demand – encouraging more drivers to work. However, this can mean that in natural disasters, it looks like Uber is profiting from ‘unfairly high’ prices. Uber has tweaked its algorithms to over-ride these equilibrium prices.

- Government controls – e.g. maximum or minimum prices or government regulating prices, e.g. train tickets limited by rail regulators.

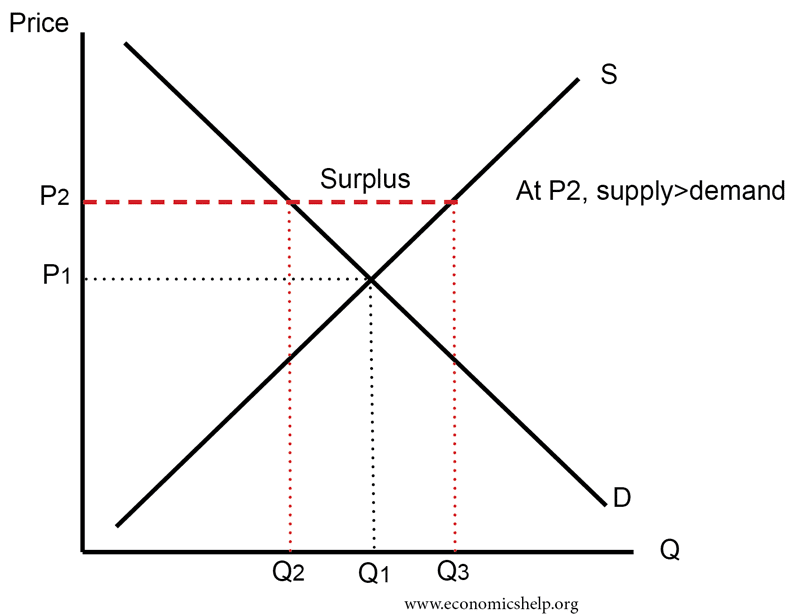

Price above equilibrium

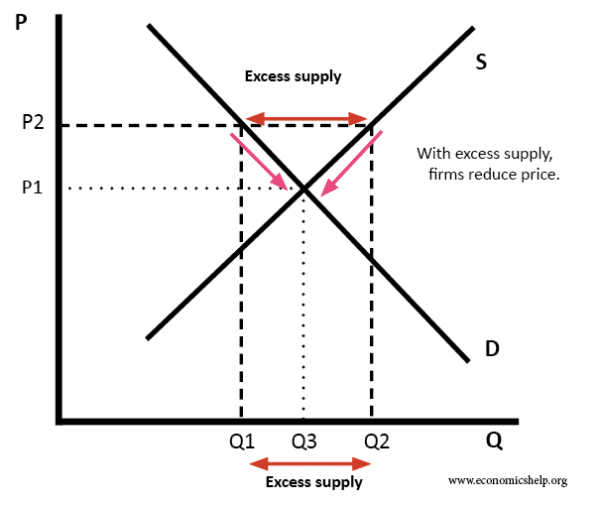

In other cases, the price may be set above the equilibrium price – leading to excess supply and a surplus.

At a price of P2, the supply is greater than demand, meaning firms have excess stock they cannot sell. There is a surplus of Q3-Q2

In a free market, you would expect the market price to fall to P1, where demand = supply.

Market equilibrium

Market equilibrium is said to occur when there is no tendency for the price to change and supply is in balance with demand.

- At P2 there is disequilibrium (excess supply)

- In a free market, the excess supply should encourage firms to cut price.

Cutting price encourages a movement along the demand curve (more is bought) - Also as price falls, firms have less incentive to supply.

- Price will fall until S= D and the market is in equilibrium.

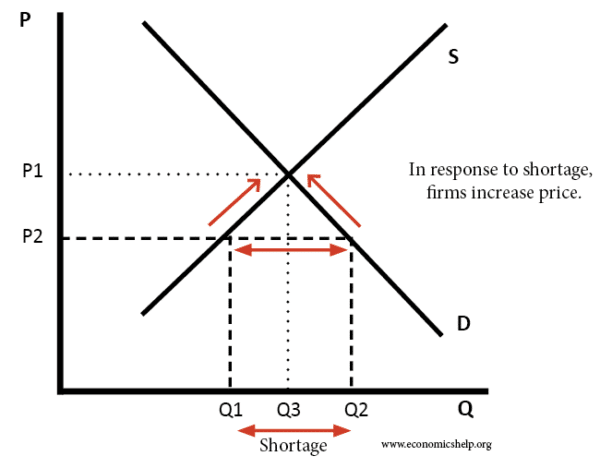

Shortage

In this case, firms will respond to the shortage by pushing up the price.

The higher price will cause a movement along the demand curve (less is bought)

Higher price will also encourage more supply

Other types of disequilibrium

- A balance of payments disequilibrium – large current account deficit.

- Labour market disequilibrium – e.g. real wage unemployment – when wages are kept above the market clearing wage, leading to unemployment.

Related pages

quite good

How to remove disequilibrium

Well, that is actually quite a difficult question, as the answer will depend on both the circumstances and your school of economic thought. Neoclassical economists would argue that prices clear over time as supply-and-demand, and thus the market, balance each other out over time. Neo-Keynesians would argue that this will only happen in the long run, because of structural factors and/or sticky prices which are slower to adapt, and that the government can play a role in bridging or speeding-up this time gap e.g. by investing or quantitative easing.

Post-Keynesian, evolutionary and institutional (but not neo-institutional!) economists however would argue that markets never clear, as they take disequilibrium economics as the normal state of the economy, in which economics are always in movement and never balance out. Empirically speaking, this does make sense, as prices are known to fluctuate, having trouble adjusting ‘instantly’ to changes in supply, demand or costs. We also know that increasing returns to scale and other advantages are a thing, which means that cumulative causation occurs (simply put, success begets success, or the rich get richer), which should not occur according to neoclassical models which work with constant returns to scale. In such cases, the government should definitely play a role to off-set social-economic and political imbalances generated by a capitalist market economy.

So, ‘simply’ put, it really depends. If there simply is a small price increase because e.g. inputs become more expensive, we could just use a neoclassical/neo-keynesian model to consider the equilibration of the prices over time, especially as the consequences will likely be limited for the wider economy. However, if there are general price increases or fluctuations (e.g. due to an oil shock or disaster) or we are concerned with the long-run, it might make a lot more sense to take an evolutionary/disequilibrium, perhaps more empirical approach to consider our options of dealing with the negative consequences caused by a specific disequilibrium, instead of thinking that we can ‘solve’ disequilibrium.

You have too much time on your hands pal

thank you for the info

Have understood

Nice and easy to understand

Thanks really helped me

Thank veri much