Readers question: Are subsidies more effective than minimum prices when supporting farmers?

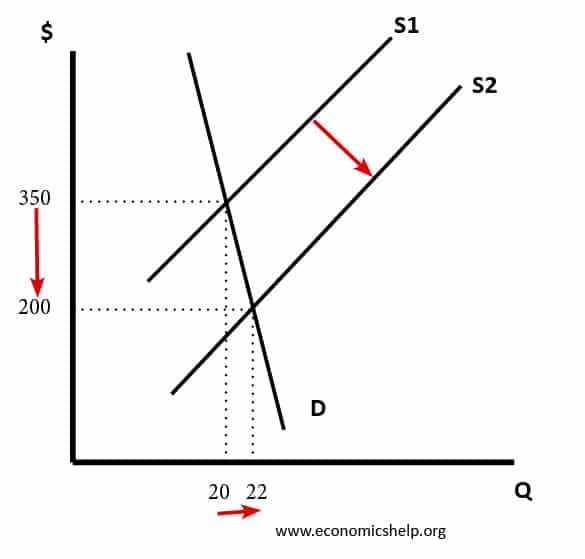

Subsidies involve governments giving money direct to farmers.

A minimum price is when the government ensures a legal price that prices cannot fall below that level. Minimum prices will increase incomes for farmers.

Farming can see volatile prices because supply can vary and demand is price inelastic. This means that one season could lead to an increase in supply and falling prices. This could risk putting farmers out of business because low prices lead to low incomes. In this case, the government may wish to intervene. Which is best offering subsidies or guaranteeing a minimum price (which will involve buying the surplus)

Advantages of subsidies

- In theory, subsidies can be directed towards farmers who are most in need to survive a downturn in fortunes. Minimum prices will give a disproportionate benefit to the largest farmers who can produce the highest output.

- In theory, subsidies can be given to farmers in return for promoting decisions which promote external benefits. For example, if there is a glut in supply, farmers could be given a subsidy to leave land fallow – which tends to be good for the environment. If a minimum price is guaranteed, it could encourage farmers to use more chemicals to maximise yields, but using more chemicals (fertilisers and pesticides) could lead to negative externalities of pollution.

- Subsidies will cost the government and will lead to higher taxes and/or lower government spending. However, minimum prices will lead to higher prices for consumers. Higher prices of food may cause hardship for those on low-incomes. With paying for subsidies, the government can choose how the burden should fall on the whole population.

- In theory, the government could give subsidies to farmers for promoting more environmentally friendly methods of farming, e.g. subsidy to move to organic farming. Alternatively, if there is a glut in supply leading to low prices, the government could give subsidies to encourage diversification away from producing that crop. For example, if there has been a global glut in grain production, the government could subsidies farmers who switch to producing new foods or move into new business altogether (e.g. tourism). A minimum price increases farmers income but doesn’t tackle the underlying problem, which is long-term over-supply.

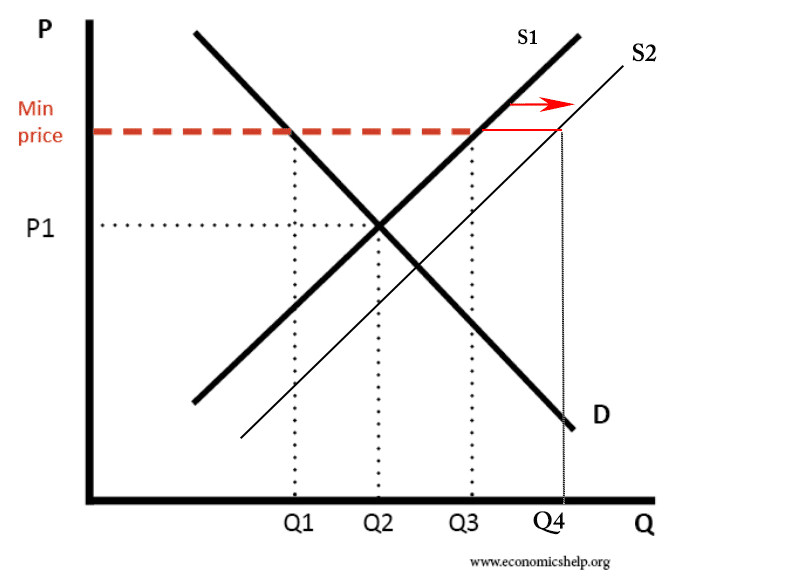

Minimum Price

The guaranteed minimum prices change incentives in the long-term. With a guaranteed high price, farmers are encouraged to expand production, this leads to bigger gluts of supply (Q4-Q1) than originally intended. This means the cost of maintaining the minimum price is higher than expected.

To maintain the minimum price the government have to buy the surplus of (Q4-Q1 * Min Price)

This then leads to the issue of what to do with the surplus. They could dump it on world markets – but this could conflict with trade treaties and cause problems for farmers in developing economies.

Advantages of minimum prices

If there is a long-term glut, then minimum prices will not be a solution. It only prolongs the problem.

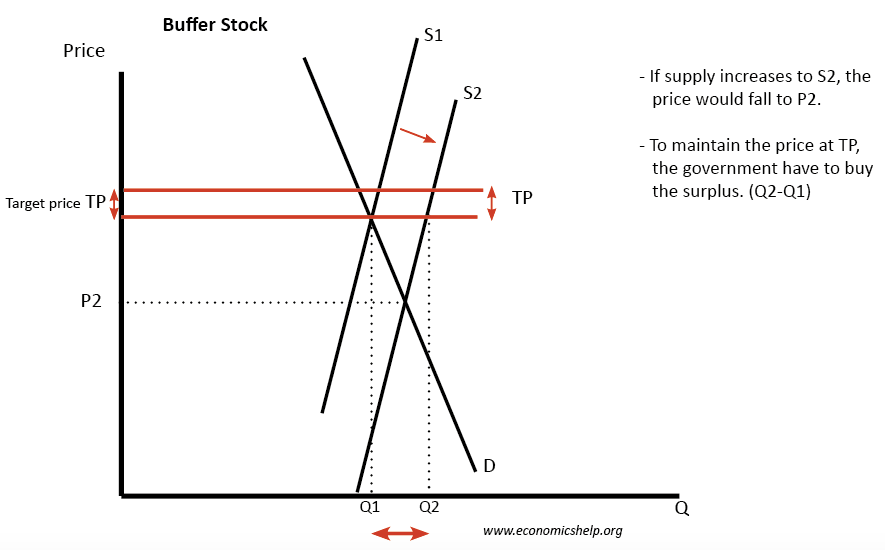

However, if the market is volatile and there is a temporary glut in supply. Then a temporary minimum price could help to act like a buffer stock. The farmers benefit from higher income during the season of low prices. The government stores the excess food supply. If next year, there is a shortage, then the government can sell from the buffer stock and ensure sufficient food supplies.

If a glut is followed by a shortage, the government can actually make a profit because they are buying for a low price, but then can sell for high price during the shortage.

If supply increases to S2 and the government sought to keep a minimum price (lower band of target price TP) then if the following year there is a shortage they can sell from the buffer stock.

A minimum price will work for products that can be stored for a long time, such as grain, seed, coffee. It will not work for more perishable items like fruit and vegetables.

Evaluation

- It depends on whether there is a long-term glut or short-term glut in supply

- It depends on how the subsidy is directed. Is the subsidy linked to production (in which case, it will encourage over-supply) or is it linked to rural benefits (e.g. promoting diversification)

Case study EU subsidies

The EU used to spend up to 75% of its budget on the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). Initially, CAP was based on minimum prices but this encouraged more supply, and the cost increased dramatically. It also caused unexpected costs such as trade disputes, higher import tariffs and environmental problems. Very slowly CAP has been reformed with a switch toward direct subsidy and away from minimum prices.

Related

Explanation was quite brief and i understood well !