The March 1981 UK budget was controversial. In a period of rising unemployment, recession and high inflation. The government pursued deflationary fiscal policy trying to reduce inflation. The chancellor increased taxes by a total of £4 billion, with the aim of reducing inflation and reducing the budget deficit.

Tax measures included

- A new 20% tax on North Sea oil was introduced.

- A one-off windfall tax on certain bank deposits was introduced, in the form of a 2.5% levy on deposits of banking businesses.

- No raising of personal allowances in a period of high inflation. So real income tax increased.

- Increase in excise duties on petrol, cigarettes and beer. Beer up 4p, spirits up 60p, wine up 12p, 20 cigarettes up 13p. Petrol duty up 20p per gallon.

Letter to the Times

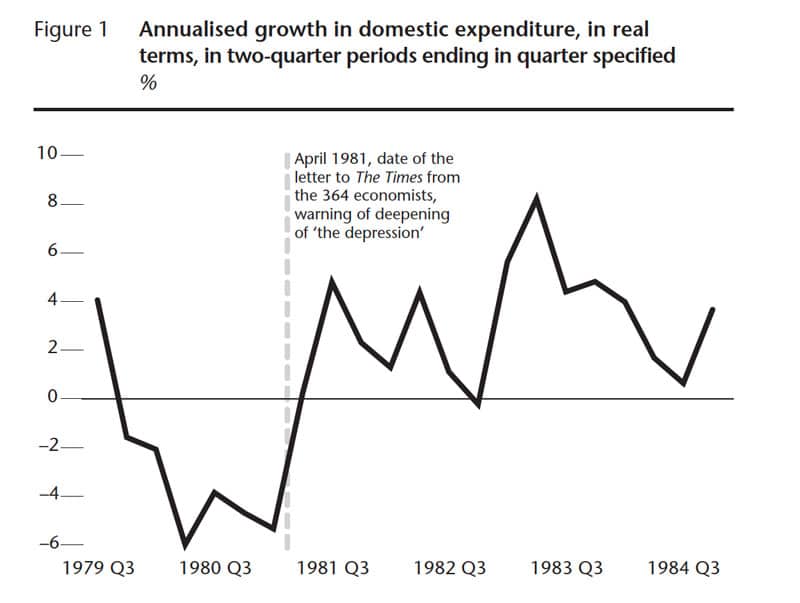

In April 1981, 365 economists signed a letter arguing the budget would worsen the recession, and that the government should end the Monetarist experiment.

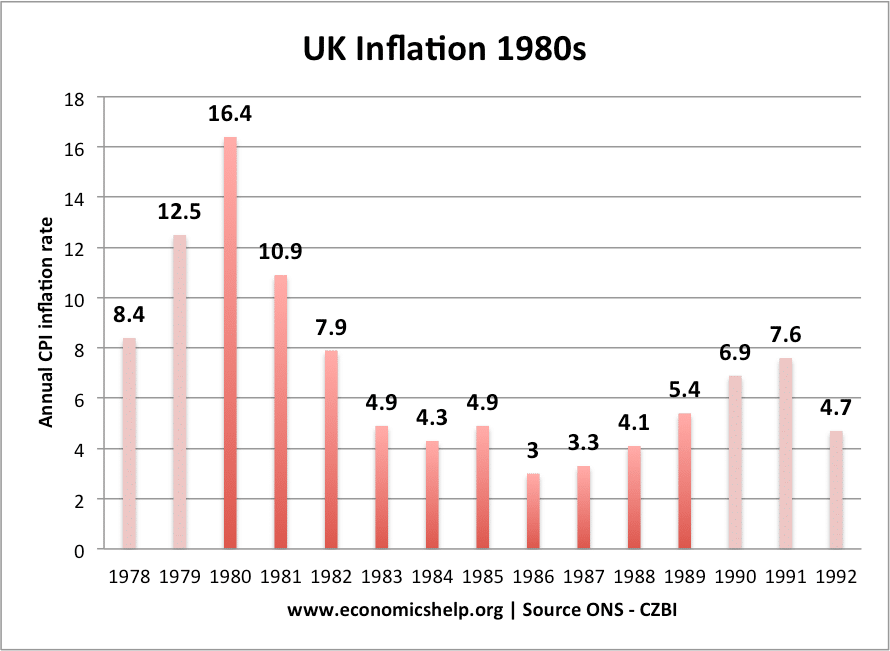

However, after the March budget, the economy recovered, and inflation fell. The immediate economic recovery suggests the Chancellor’s deflationary fiscal policy did not harm the economy – but gave the benefits of lower inflation and lower government borrowing. However, his critics argued unemployment continued to rise, and some economists still argue the budget was unnecessarily deflationary and it contributed to a slower economic recovery than possible.

From this evidence, the economists were wrong to predict the deflationary fiscal policy of the budget would worsen the recession.

Inflation also fell.

Unemployment continued to rise

On the other hand, unemployment continued to rise, suggesting growth was significantly below the trend rate and there was a continued persistence of a negative output gap. Unemployment peaked on the OECD measure at 12.5% in 1983 but did not fall below 11% until 1987. (Bank of England) On the measure of unemployment, you could argue the economists were right to say deflationary fiscal policy would damage economic prospects.

One important outcome of the 1981 budget was the clear sign that the government were prioritising inflation over unemployment. The average unemployment rates of the ‘monetarist period’ were significantly higher than the unemployment rates of the ‘Keynesian period. In the Keynesian years from 1956-81, it averaged 3.7% of the labour force [1] (though it should be remembered using stats like this only tells part of the overall picture )

Does recovery disprove Keynesian economics?

In Keynesian economics, it is a mistake to only consider the impact of fiscal policy on the economy. Several other factors affect aggregate demand – interest rates, exchange rates, global growth, asset prices and consumer confidence.

– In 1981, the economy had experienced a deep recession, leaving substantial spare capacity. It meant that the natural economic cycle was set to swing into recovery. Parts of the economy were already recovering as the budget was introduced. You could argue the deflationary fiscal policy meant a slower recovery than otherwise would have happened. But, if you predict the recession will worsen and you immediately get positive growth, it becomes a mistake of the economists who signed the letter.

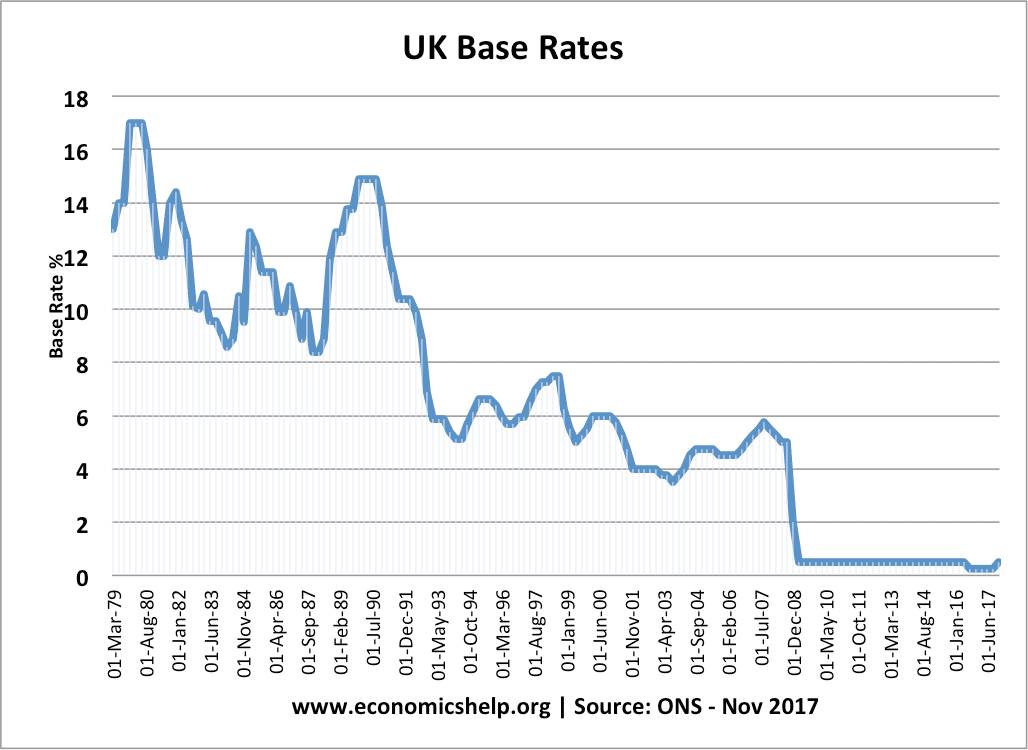

Interest rates fell At the same time as the budget, interest rates were cut from 14% to 12%. To some extent, this offset the fiscal tightening. However, the monetary easing isn’t straightforward – by 15 September interest rates were back to 14%, and in October they rose to 15%. Nevertheless, in 1982, interest rates fell significantly giving a substantial monetary easing to offset the tighter fiscal policy in 1982.

Other factors were also helpful for boosting economic growth. Productivity growth was unexpectedly high in the period 1982-86 (3% was above previous trends.)

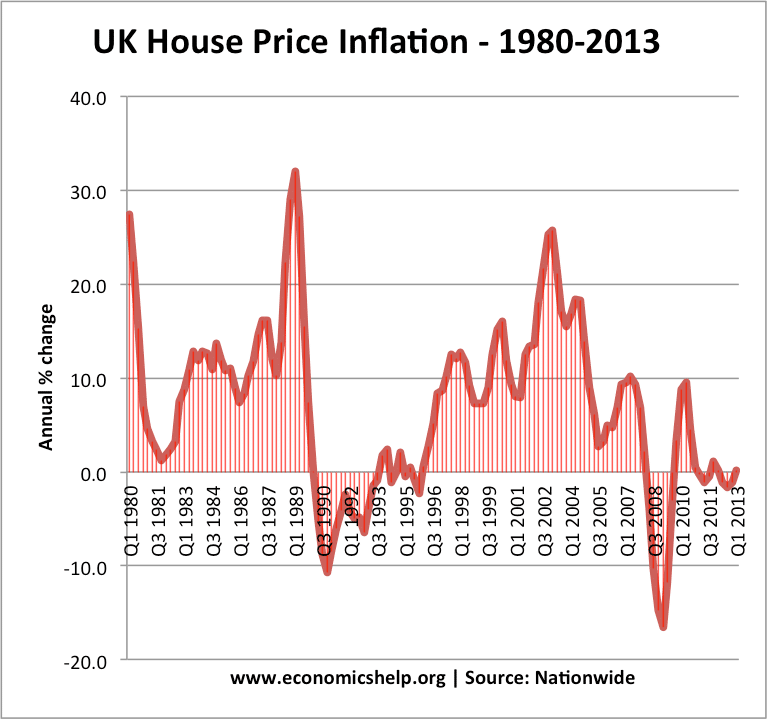

After 1981 recession, house prices rose. Rising asset prices created a positive wealth effect and improved consumer spending.

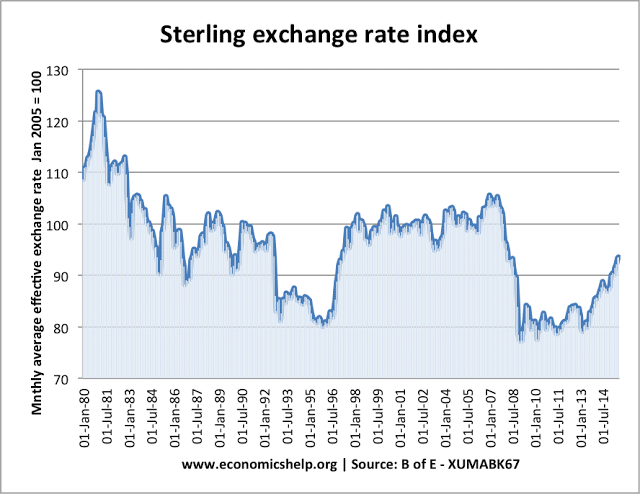

After its peak in 1980, Sterling underwent a significant depreciation in the early 1980s making exports cheaper and imports more expensive. This provided a boost to domestic demand at a time when the global economic was beginning to recover from the previous global slowdown.

Cheaper petrol

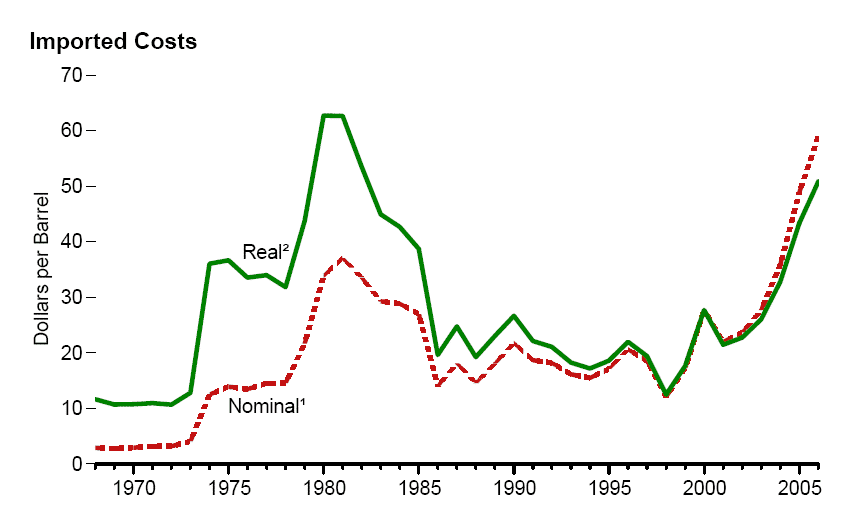

The increase in fuel duty was quite striking (20p a litre!) However, the rapid increase in fuel duty was partially offset by the decline in oil prices in the early 1980s.

It depends on the type of recession

The 1980/81 recession was caused by factors reducing demand (high sterling, high interest rates, tight fiscal policy). This meant that for any of these to be eased means the economy should recover quickly. (for example after 1992 recession, there was a mini boom with growth averaging 4%)

Contrast this with the balance sheet recession of 2008/09 – where bank losses meant cutting interest rates wre ineffective.

The 1981 recession was caused by temporary demand side factors, it is easier for the economy to recover.

Conclusion

The economists were wrong to predict a worsening of the recession. But, the spirit of the letter was not entirely wrong. A deflationary budget in a recession arguably slowed the recovery and kept a negative output gap – causing 3 million unemployed until the mid 1980s.

However, it also shows that it is quite possible to raise taxes, reduce the budget deficit and allow an economic growth – so long as there is other avenues for allowing growth. In 1981, the biggest factor was the recessionary cycle was coming to an end. And buoyed by falling sterling, falling interest rates and rising house prices, in hindsight a recovery looked much more likely than if were just looking at the grim statistics of April 1984.

It’s not clear Keynes would have signed the letter. He didn’t just believe in fiscal policy but was aware of the impact of interest rates and exchange rates on demand.

A big contrast is between 1981 and 2007. 2007/08 was a very different kind of recession, because cutting interest rates was insufficient. In those circumstances of very low inflation, very low interest rates, deflationary fiscal policy (austerity) did cause a ‘second-dip recession’ with the negative output gap never overcome

Irony

I quite like some aspects of the 1981 budget – higher petrol tax is good for reducing pollution and congestion (Fuel duty). One off windfall tax on bank accounts, and tax on North Sea oil is redistributive.

Further reading

- The budget of 1981 was over the top – Stephen Nickell, Member of the Monetary Policy Committee, Bank of England

- 364 economists with one opinion

Really interesting. I recall from about 1989 a comment on the news (BBC radio 4 Today programme?) that the public finances were then so healthy that if they continued this way, by 2000 we would either have no national debt or no income tax. I know this was during the ‘Lawson Boom’, but do you know if this was true? And if it was then the economists must have been wrong.

I recall from about 1989 a comment on the news (BBC Radio 4 Today program?) that the public finances were then so healthy that if they continued this way, by 2000 we would either have no national debt or no income tax…