The Labour Party manifesto commitment has numerous spending commitments. These are financed by a mixture of government borrowing and tax increases. Would the increase in spending and borrowing lead to higher interest rates?

In summary – the most likely effect would be a short-term fiscal expansion, which could lead to higher growth, a rise in inflation, and therefore, upward pressure on interest rates – But, this return to higher growth and higher interest rates would in many ways be quite welcome.

In the long-term, very generous spending pledges on things like pensions could lead to a significant rise in debt to GDP, where the impact on interest rates are more uncertain.

Labour plans in brief

- Day-to-day spending is forecast to rise by £80 billion in 2023–24 (10% increase on current levels.

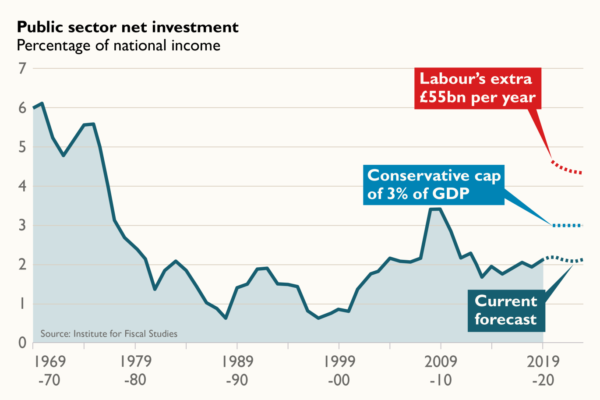

- Increase investment spending by £55 billion a year, a doubling on current levels. (IFS)

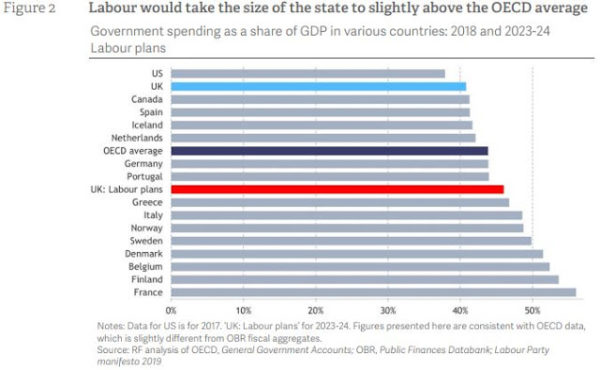

This would represent a significant increase in the proportion of government spending within the economy. It is a radical departure for UK, but would still place the UK below other European countries with larger states.

Public sector investment as a % of GDP has fallen significantly since 2010, Labour’s investment plans would see the UK rise up the ‘league table of public sector investment’. It is not unprecedented for the UK to have such levels of public sector investment.

Would interest rates rise?

Interest rates can rise for various reasons

- A rise in inflation

- Higher economic growth

- Unsustainably higher debt and potential fear of debt default, pushing up bond yields as investors demand a better return on holding government debt.

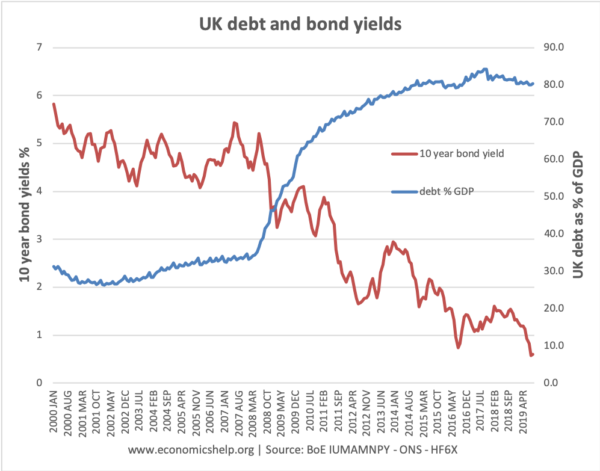

Firstly interest rates are at record lows

Since 2010, there have been numerous predictions that interest rates would rise only for the predictions to be proved false.

Expansionary fiscal policy

The extra public spending financed by borrowing and increasing corporation tax would likely prove to be expansionary fiscal policy. It would represent an increase in aggregate demand and lead to higher economic growth – at least in the short term. If the boost to demand is sufficient, then it may begin to cause some inflationary pressures. This inflation could persuade the Bank of England to raise interest rates, and the higher growth and inflation would likely push up bond yields on government debt. (not because of fear of default, but with higher growth investors are more willing to buy corporate bonds which give better return than government bonds)

Evaluation

It is not certain even Labour’s spending plans would be a sufficient boost to cause a return of inflationary growth. Since 2010, economic growth has been lacklustre, the forecast for 2020 put UK growth at around 1%. With Brexit uncertainty still weighing down business investment, growth may remain at current levels and not cause interest rates to go up.

Crowding out?

It is possible that higher government spending could lead to an equivalent fall in private sector spending (known as crowding out). If corporation taxes rise, then the private sector may reduce their investment levels. In this case, there wouldn’t be an overall increase in aggregate demand. There is a debate about the extent to which corporation tax levels influence investment, but a bigger factor is prospects for investment tends to be economic growth and stability.

It is very unlikely there will be 100% crowding out. The private sector have been reluctant to invest for several years – due to poor growth prospects. There are unused savings – as shown by the great demand to buy government bonds – despite very low-interest rates. You don’t tend to get crowding out, when growth is so low.

Would an increase in borrowing cause investors to demand higher bond yields?

One argument is that a rapid increase in borrowing could cause investors to look more nervously at UK government bonds. Investors may feel that borrowing commitments are unsustainable in the long-term and that the UK government is at risk of potential default.

This is highly unlikely – though not impossible. With inflation very low, markets don’t fear liquidity shortages as the Bank of England can offer intervention in the bond market – through purchase of bonds if needed. Also, if borrowing is to fund public sector investment, this should provide some long-term benefit to the economy.

The UK has never defaulted on its debt (though in the 70s, high inflation gave a kind of partial default_ Though Labour’s plans are ambitious and (some might argue reckless – The IFS argues Labour tax plans will not raise as much as they claim because the tax base is too narrowly focused). It still leads to a level of state spending that is not unprecedented. The national debt has increased by £600bn during the past nine years – but interest rates fell in this period. The market appetite for government bonds often surprises observers. There is

Would a rise in interest rates be a good thing?

Interest rates of 0% are highly unusual and unprecedented. Economists generally agree that in the medium term, it is better for interest rates to return to more ‘normal levels.’ Interest rates of 0% can distort some economic decision making – favouring borrowers over savers. A fiscal boost which Labour propose could, in theory, return the economy to a more normal trajectory of economic growth, and this would cause interest rates to return to normal. But This would be beneficial from an economic perspective.

If we did return to a higher rate of economic growth – this would also boost tax revenues, which may make it easier to fund spending commitments. However, it would also start to raise the cost of interest payments.

Evaluation

It is tempting to look at Labour Party spending and see it as a fiscal boost which will cause higher growth in short-term (and possibly medium/long term) – and this will lead to higher interest rates. However, the only certainty of the past nine years is that predictions of interest rate increases (of which there have been many) have not materialised. If you predict rising interest rates you need to be ready to be proved wrong.

Are Labour’s borrowing plans reckless?

The manifesto had some good commitments – investment in NHS, Green new Deal. Public sector investment has fallen to very low levels by international and UK standards. There is definitely a case for increasing public sector investment for areas like housing and infrastructure. But, as well as public sector investment, economists will be much more concerned at very expensive pension commitments. Keeping the pension age at 66 would add £24 billion a year to spending by the 2050s (IFS) – but this gives no supply-side boost to the economy – in fact it will lower labour supply as people retire earlier.

The Labour party’s very recent announcement it would recompense £58bn to WASPI pension – funded apparantely by government borrowing (no spending cuts or tax rises were mentioned) is the kind of spending commitment that does concern economists. It is one thing to borrow to fund public sector investment, but it is very different to fund pension transfers.

Related