Since 2016, the UK economy has performed poorly, – weak Pound, high inflation, falling real wages, and a worrying decline in business investment. There are mitigating factors, such as Covid and the Ukraine war, but despite this, the UK seems to be performing relatively badly compared with other countries, with one of the lowest rates of growth and the IMF making dismal predictions for 2023. I have written about the costs of Brexit. But, will now try examine five potential benefits to see how valid they are.

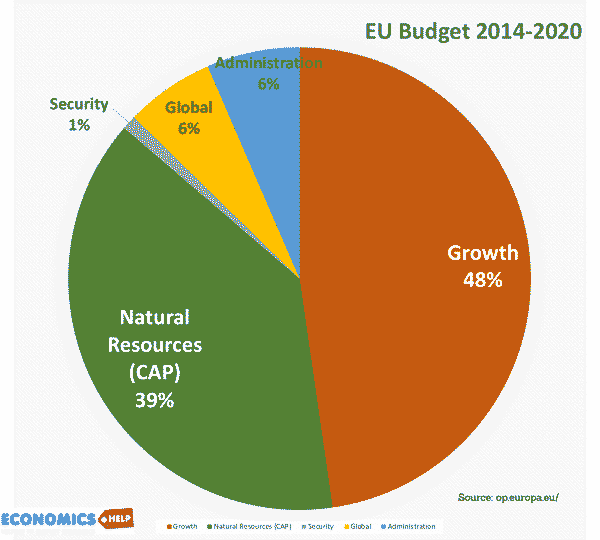

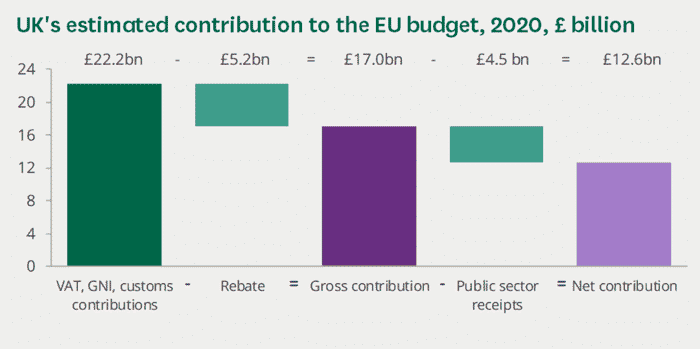

Firstly a strong economic benefit is being able to leave the EU Common Agricultural Policy. It takes around 38% of the EU budget, costs €58bn and wastefully gives subsidies to the richest landowners. It works by setting minimum prices, with the EU agreeing to buy surplus. It also requires high import tariffs of around 4–40%, which damages the EU’s ability to negotiate free trade deals. The OECD suggested it led to a European family of four paying more than $1,000 a year in higher food prices and taxes. The EU has tried to reform CAP and replace minimum prices with direct income support for landowners with farmland. But this has encouraged the destruction of wildlife habitats to be eligible for farm subsidies. The Economist reports agricultural intensification led to more biodiversity loss in Britain than global warming or urbanisation combined.

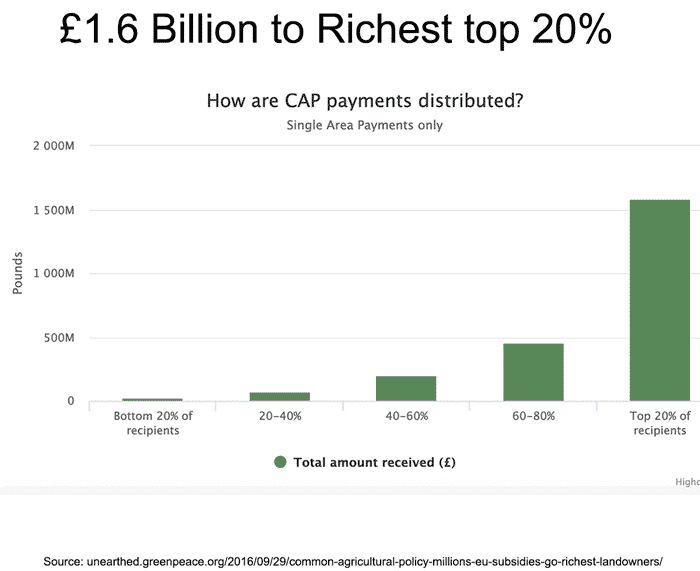

Direct income support scheme is related to the amount of land owned. It has rewarded wealthy landowners. Recipients of EU subsidies include the Queen, Sir James Dyson, Paul Dacre owner of the Daily Mail, and foreign landowners such as Prince Khalid bin Abdullah al Saud. We cap benefit payments to the poorest, but with EU subsidies the wealthier you were, the more you were entitled to. The payment per land also encouraged land speculation with wealthy buyers buying up farmland. According to Savills, the price of farmland rose from £4,500 per hectare (2003) to about £16,500 in 2020. Bigger than the price rise for UK housing. It made it difficult for young local farmers unable to buy land. CAP also disadvantaged the UK because of its relatively small farm industry compared to France, Spain and Germany.

Outside CAP, the government have the opportunity to use tax payer funds more fairly and target directly for environmental and social reasons. For example, the sustainable farming incentive (SFI) which rewards farmers for protecting the environment. However, after Liz Truss briefly threatened to cancel the scheme. Farmers are complaining they have seen very little of the new form of subsidies. So far only £10 million (0.44%) out of the £2.4bn budget has been spent. British farmers are also worried about the loss of access to the Single Market and being overwhelmed with cheap imports from Australia and New Zealand.

In 2020, the UK made a net contribution to the EU of around £12 billion, with 38% going towards the largely inefficient common agricultural policy. Leaving the EU gives the chance for more efficient use of funds – nothing like the £350 million claim a week for the NHS, but at least an agricultural policy that doesn’t reward rich landowners

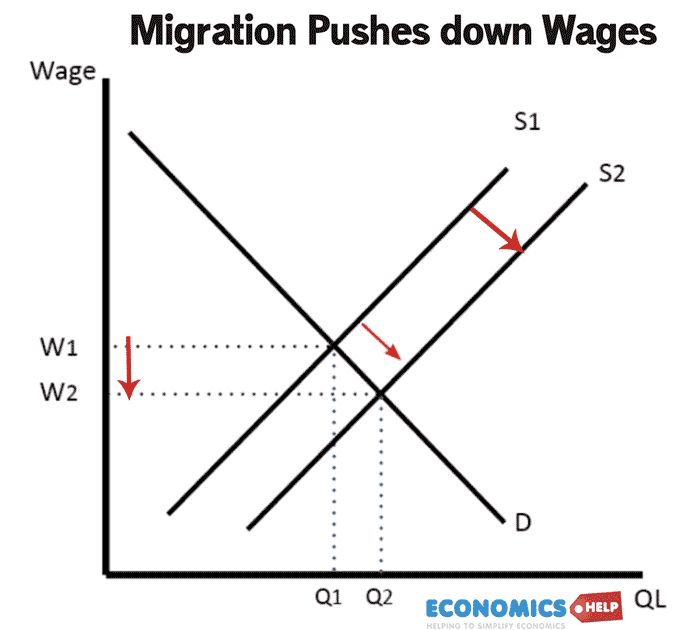

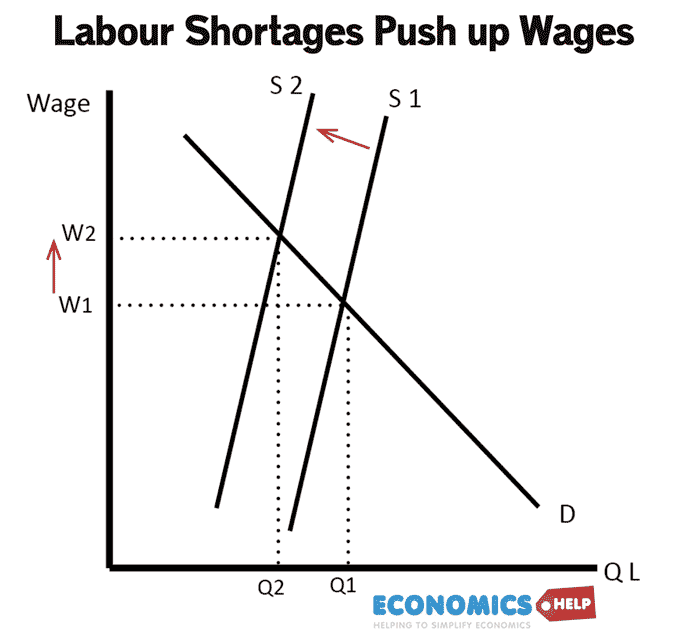

The next claimed benefit of Brexit, is more contentious. The argument is that free movement of labour encouraged firms to rely on a low wage economy. With Brexit contributing to labour shortages, it is argued wages will rise and firms will invest in boosting labour productivity.

For example, farmers used to be able to rely on cheap labour from eastern Europe to collect crops. With this supply greatly reduced it now becomes more economic for farmers to invest in automatic robotic collection of food, the kind of investment that would increase productivity and real wages in the long-term.

There are a number of issues with this.

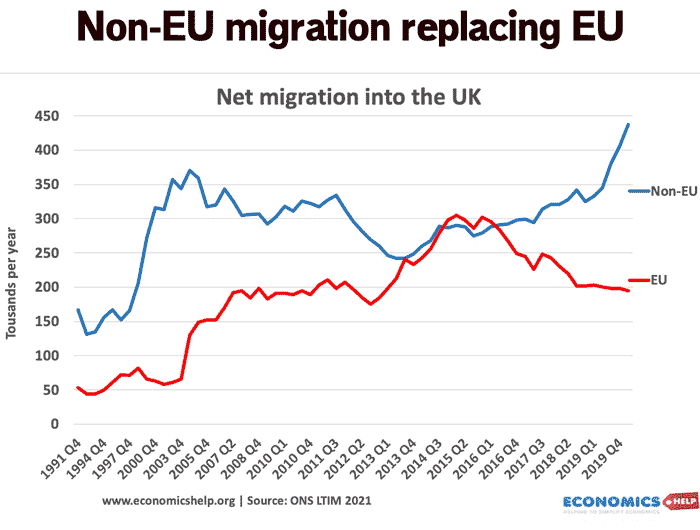

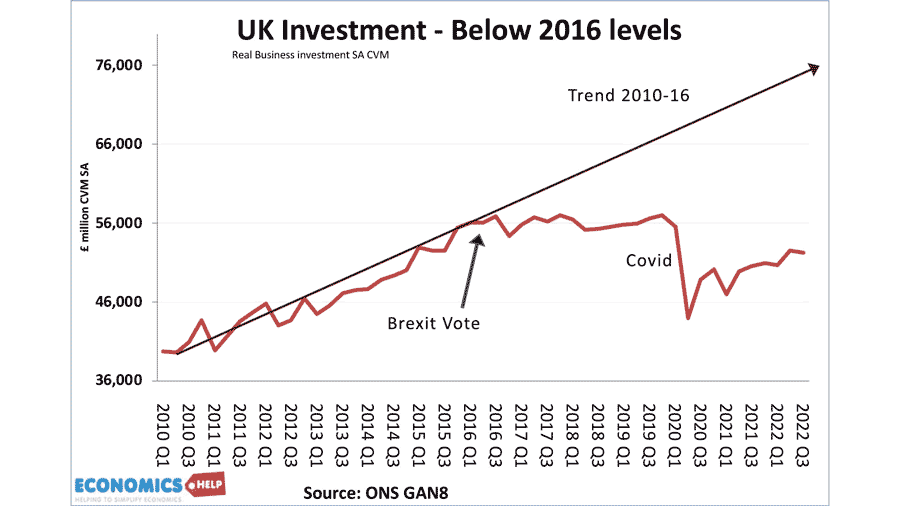

Firstly, net migration has not fallen post-Brexit. EU migration has declined, but it has been offset by a rise in non-EU migration. Secondly, the biggest labour shortages are in areas like care assistants, nurses, hospitality workers and construction. Jobs which cannot easily be substituted for capital. Thirdly, there have been historic low levels of investment since Brexit.

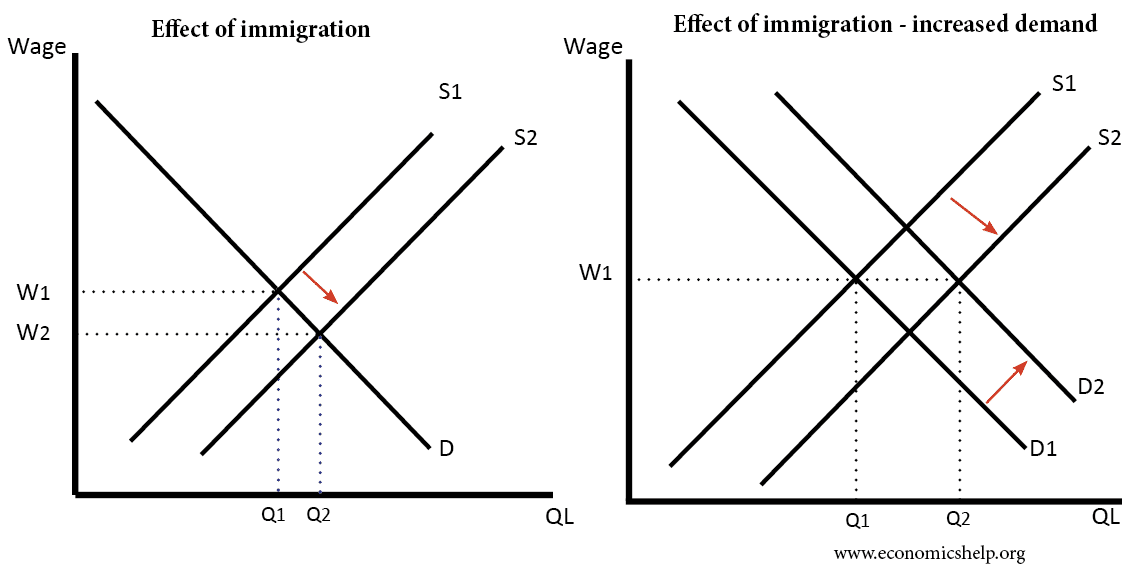

The problem is primarily lack of demand and weak growth. Finally, it is debatable whether high migration leads to lower wages – Net migration in the 90s and early 2000s were consistent with rising real wages. Low wage growth post-2009, wasn’t so much net migration but underlying issues in the UK economy. It is possible over time, there will be a resurgence in capital investment and post-Brexit Britain will see rising labour productivity, but there is no evidence yet.

Also, the above diagram of migration causing a rise in labour supply decreasing wages is a lump of labour fallacy, because migration also increases labour demand.

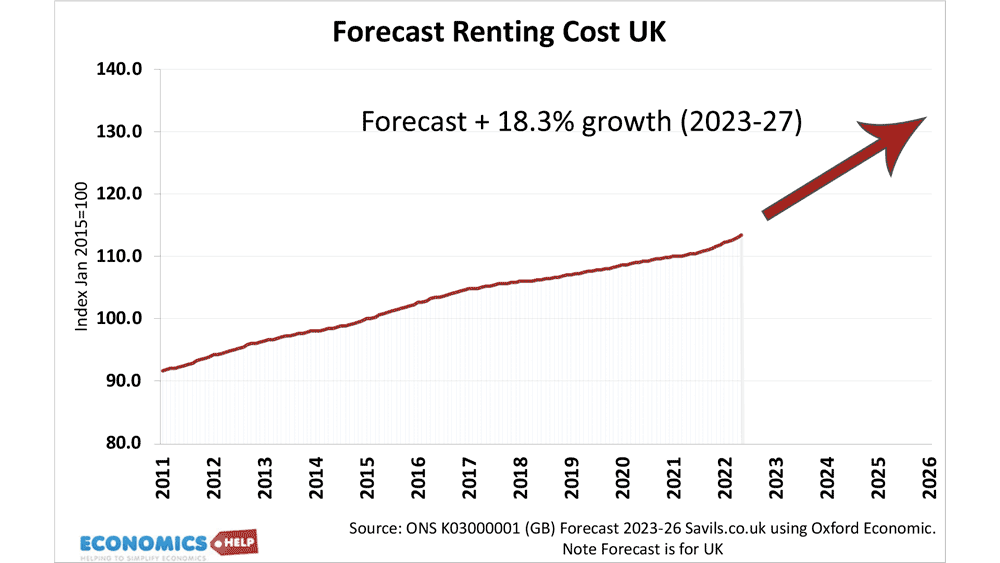

A third possible benefit of Brexit is that without the decline in EU migration, there would have been even bigger increase in demand for rental properties. Rental prices are going through the roof because of a shortage of supply. High levels of migration post 2000, contributed to rising house prices, squeezing living standards, especially for the young. If the UK is unwilling to build enough housing, then you might need to look at restricting migration growth. Of course, a different solution would be to tackle the housing crisis directly.

A fourth possible economic benefit of Brexit is touted as free trade deals with non-EU countries. A government press release claims that a recent deal will increase trade with Australia by 53%, boost the UK economy by £2.3 billion and add £900 million to household wages in the long run. However, this is somewhat misleading as they mean over the next 15 years. In the best-case scenario, it merits a 0.08% increase in GDP by 2035. Not quite statistically insignificant, but only a small fraction of the impact of trade with the EU. Former cabinet member George Eustice criticised the deal for giving too much away in a rush to get a deal and damaging UK farmers.

A fifth potential Brexit benefit could come from deregulation. In fact, some argue that until we remove all EU legislation, we haven’t really ‘done’ Brexit. In theory, deregulation and lower taxes could attract investment and boost competitiveness Although it is worth bearing in mind, Ireland already has a very low corporation tax as an EU member. Secondly, whilst in theory, deregulation could reduce costs it is not particularly a priority for business. The British Chambers of Commerce report a majority of firms do not prioritise deregulation and are more concerned about weak demand. Removing regulation would have both pros and cons, with the EU likely to retaliate against a perceived threat to its single market with higher retaliatory tariffs and more checks.

These are five potential benefits of Brexit. Of the five, leaving CAP has the strongest case for a long-term benefit. However, at the moment, if we put them in context against the increased trade frictions, and decline in investment, they are relatively minor and more of a silver lining in a fairly dark cloud. Of course, there is much more to Brexit than economics, but if you think I have missed any economic benefit, feel free to leave a comment. And if interested, this video looks in more detail at the costs of Brexit.