In 1967, the UK government of Harold Wilson devalued the Pound from $2.80 to $2.40 (a devaluation of 14%). It was a major political event because the government had tried hard to avoid a devaluation, but felt forced into the decision because of a trade deficit, a weak domestic economy and external pressures from creditors.

Background to devaluation of 1967

The government pursued an exchange rate peg of £1 to $2.80. A strong Pound was seen as important for maintaining living standards and providing an incentive for manufacturers to increase productivity to stay competitive. There was considerable political capital related to devaluation. The Labour government was concerned a devaluation would be seen in a negative light by the electorate.

Economic background

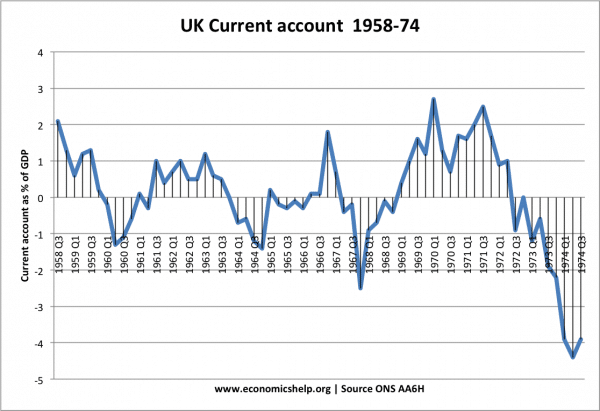

Trade deficit. The UK was mostly running a deficit on the current account balance of payments throughout the 1950s and 60s. By today’s standards, it was a small % of GDP, and in some quarters there was even small surpluses, but the trade deficit was still perceived to be a major economic problem. To finance the current account deficit required capital flows or the use of diminishing foreign exchange reserves.

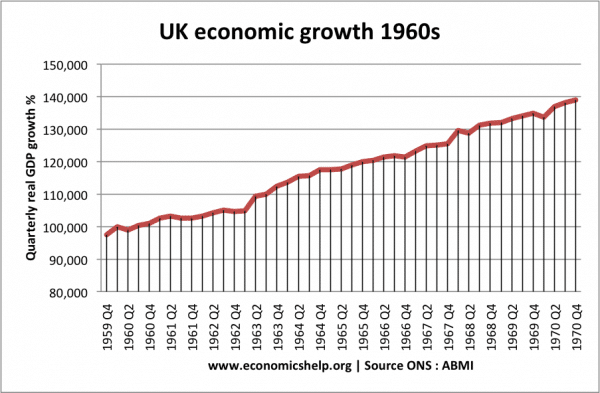

Relatively lower UK productivity. A problem facing the UK economy was a relative decline in productivity compared to European and US competitors. This made UK goods less competitive, leading to a trade deficit. In a floating exchange rate, lower productivity tends to cause depreciation. By keeping a fixed exchange rate, the government were battling against long-term trends.

UK convertibility and reserve currency. In 1958, UK Sterling was made fully convertible. This attracted significant Sterling holdings by overseas governments. But, these large Sterling reserves ( £4.5 billion in sterling balances banked in London. (link) meant the Pound was more subject to the moods of foreign investors. Poor economic data encouraged these external investors to sell, making it more difficult for the UK government to protect the value of Sterling.

Creditors. To maintain the exchange rate peg, the UK government borrowed from the IMF and Central Banks to keep the value of the Pound high. This meant they needed to pursue an economic policy designed to pay back creditors. It also led to the government running out of gold and foreign currency reserves.

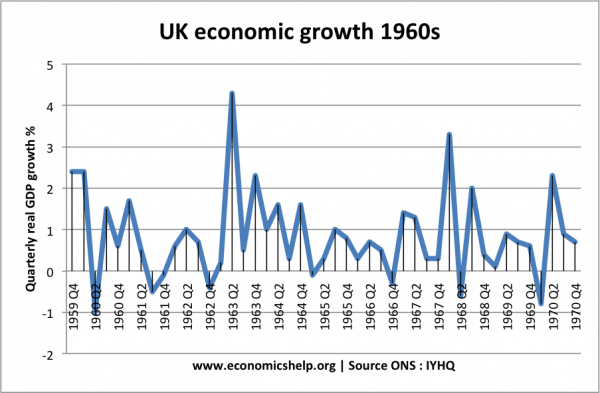

Conflict with other objectives. In the mid-1960s, the government sought to promote the export sector and limit the growth of domestic demand – to limit import spending and boost exports. This was motivated by the need to reduce the trade deficit and keep sterling strong. However, 1967 was a year of lower global economic growth. The Six-day war raised the cost of petrol and the UK had to spend more on imports. At the same time, exports were hit by the slowdown in global growth. To compound matters, there was a dock strike of 1967 which hit exports.

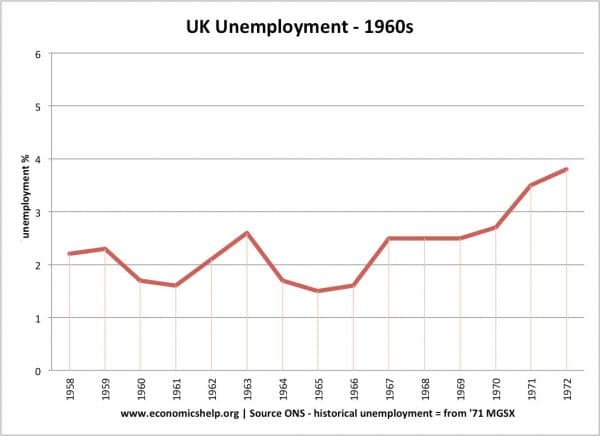

Weak domestic demand saw a rise in unemployment from 280,000 (1.3%) to 540,000 (2.3%) in mid-1967. In response, the government cut interest rates from 6.5% to 5% and relaxed hire-purchase restrictions to try and selectively reflate the economy. But, this led to higher import spending and a deterioration in the trade balance. The poor economic data (higher trade deficit, lower growth, rising unemployment), encouraged investors to sell Pound Sterling, leading to lower reserves.

In October and November, the Bank of England increased interest rates 1%, but this failed to reassure investors the government was doing enough to protect the value of the Pound. In November, the government felt there was no choice but to devalue.

Impact of devaluation

Harold Wilson made a speech, in which he said:

“It does not mean that the pound here in Britain, in your pocket or purse or in your bank, has been devalued.”

What he was trying to emphasise is that devaluation does not directly lead to a devaluation of the internal value of money. Only when you buy goods from abroad. (though customers the price of imported goods are likely to rise)

The economy recovered by the end of the 1960s, but it was not enough for the Labour government to win the election of 1970.

The current account improved until the early 1970s when the current account went back into deficit.

Inflation

After 1967, UK inflation rose, partly as a result of the devaluation.

Conclusion

The official exchange rate peg of £1 to $2.80 was difficult to maintain. The government were having to sacrifice other objectives – caught between limiting domestic demand (through higher interest rates) and then worrying about the higher unemployment.

Given long-term decline in competitiveness, the exchange rate was overvalued and so most commentators see the devaluation as inevitable. Trying to keep the Pound overvalued would harm further the economy.

After the devaluation, there was no economic miracle, growth remained below our competitors, inflation rose, and it did not solve the underlying issues in the UK economy. However, without a devaluation, the economy would have had more serious problems and may have needed even higher interest rates and a prolonged period of deflationary pressures

Related