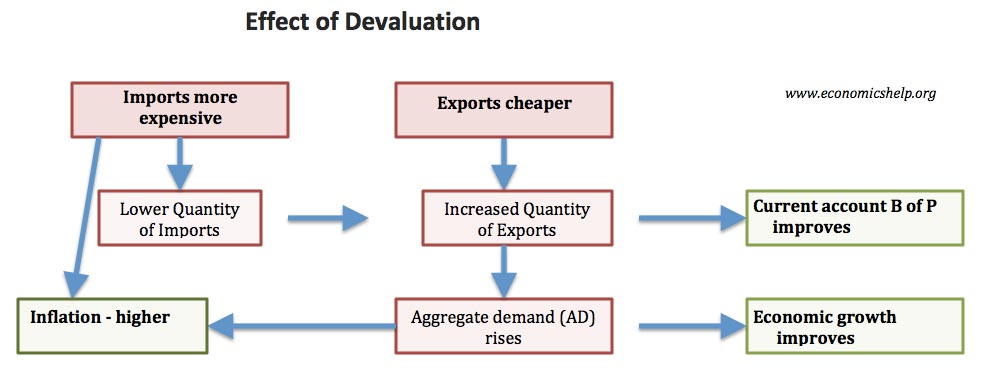

A devaluation (depreciation) occurs when the exchange rate falls in value. This causes exports to be cheaper and imports to be more expensive. In theory, it can help increase economic growth, though it may cause inflation.

In theory, a devaluation will cause the following to happen:

- The price of UK exports will be lower in foreign currencies. This will increase the competitiveness of UK exports and should cause an increase in demand for UK exports.

- The price of imported goods into the UK will increase. This will reduce our spending on imports and instead we will be more likely to buy domestic goods.

- The increase in (X-M) should cause an increase in Aggregate Demand (AD), economic growth and cause a reduction in unemployment.

- The increased competitiveness should cause an improvement in the current account on the balance of payments.

Evaluation

The impact of a devaluation depends on economic circumstances.

- If a country is suffering from being uncompetitive with high unemployment and low inflation – a devaluation may help considerably.

- However, in a severely depressed global economy (e.g. 2008-13), a devaluation may be insufficient to restore economic growth.

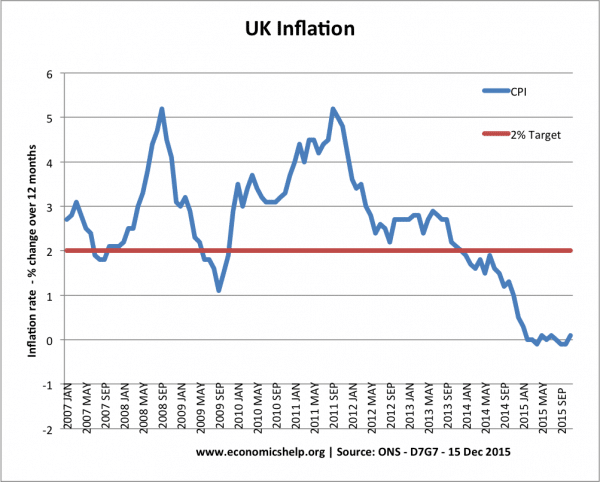

- The fall in the value of the Pound (2016) is partly due to concerns over Brexit (British exit from EU). This is causing uncertainty and will likely to reduce investment from export firms. In this situation, the devaluation will probably do little to boost economic growth. However, with inflation near zero, the usual inflationary pressure of devaluation will not be a problem.

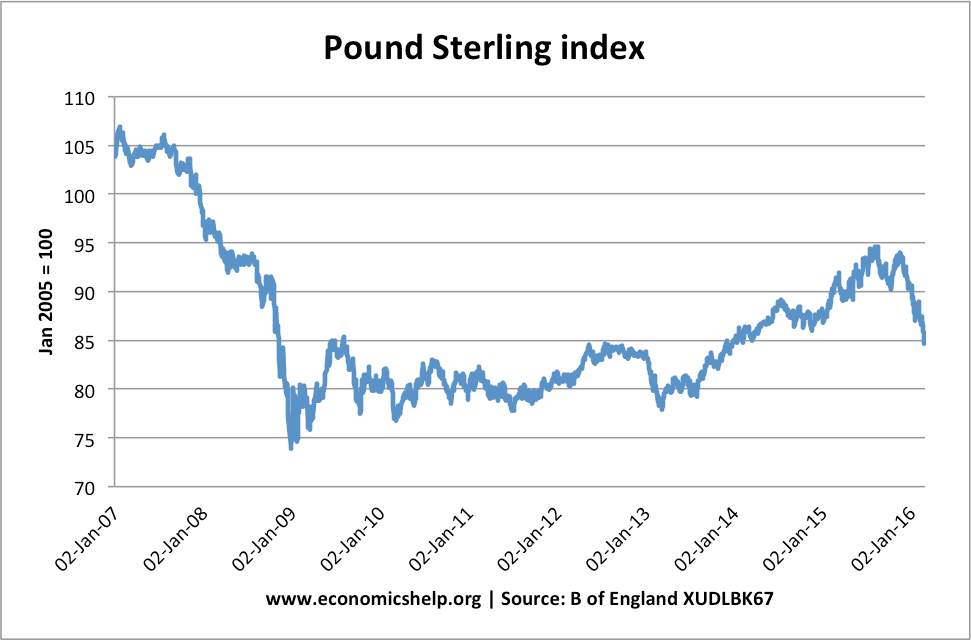

UK Devaluation between 2008 and 2013

Between 2008 and 2013, the Pound experienced a 25-30% devaluation in Sterling, but the UK had only a weak recovery, some cost push inflation and a surprisingly large current account deficit. It seems the depreciation in the pound did little to help the UK economy. This was due to several factors

- Demand for exports and imports relatively inelastic. UK continued to import more expensive German cars, but export demand also inelastic.

- Weak Eurozone growth. 2008-13 was a period of low EU growth, therefore more competitive UK exports were insufficient to boost export demand.

- Fiscal austerity and fall in bank lending were major factors depressing the economy. Therefore, the devaluation was insufficient to compensate for the fall in other components of AD.

Pound Sterling Index

Impact of devaluation on economic growth

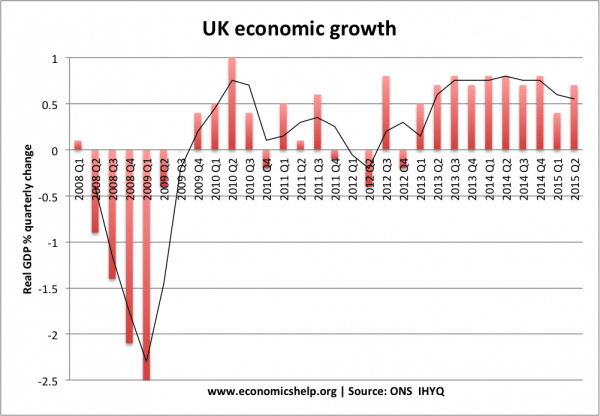

1. Economic growth. In terms of economic growth, the five years after 2007/08 devaluation were relatively low. The devaluation was insufficient to stop the deepest recession for a long time, and the recovery was weak – compared to other recoveries. (see: Comparison of different recessions)

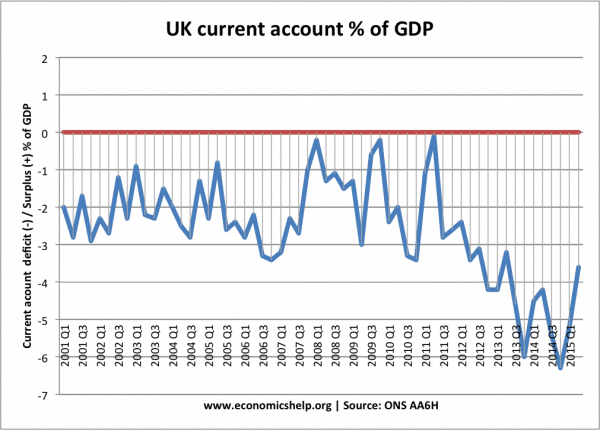

2. Current account deficit. The current account deficit actually got bigger from 2010.

In 2008, the current account deficit was less than 2% of GDP. At the end of 2013, this current account deficit fell to more than 5% of GDP – a very high deficit (more at current account balance of payments) This seems to contradict economic theory – as you would expect a devaluation to improve the current account – not worsen it.

How do we explain the relative failure of devaluation to rebalance the economy in UK 2007-13?

1. Inelastic demand for exports and imports Evidence suggests that demand for UK exports is relatively inelastic. UK exports have become less price competitive as we’ve moved away from low-cost manufacturers to a variety of services and high-tech manufacturing; these goods tend to have relatively few close substitutes. Therefore, even if the price falls, the increase in demand is relatively low. Similarly, demand for imports is relatively inelastic meaning we continue to pay the higher price. (The Marshall-Lerner condition states a devaluation will worsen the current account if PEDx + PEDm >1)

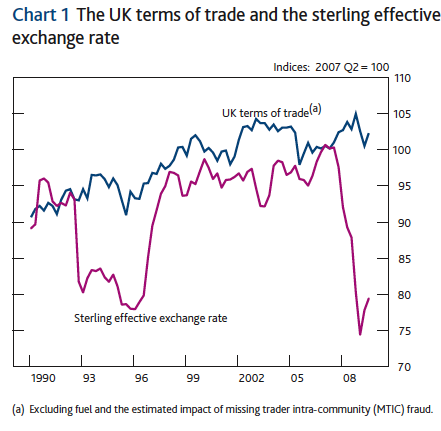

2. Firms didn’t always pass on the effects of devaluation. In theory, devaluation leads to a lower price of exports. However, firms could choose instead to keep the foreign currency prices the same, but increase their profit margins instead. Rather than passing the devaluation onto foreign customers, UK exporters just make more profit. In a recession, exporters are keen to improve their cash balances and so are keen to increase profit margins.

In 2008, the Bank of England showed that the rapid devaluation hadn’t caused a fall in the UK terms of trade. UK export prices didn’t fall, but actually increased. It explains how a devaluation may not cause lower export prices – at least in the short term.

3. Weak external demand

A devaluation is not much help if your main export partners are in a recession. The double dip EU recession means there has been a fall in demand for UK exports. This has outweighed the more competitive prices. The weak external demand is a key factor in disappointing current account figures.

4. Higher import prices

The problem of devaluation is that it leads to higher import prices. Raw materials used in production increase in price and contribute to cost-push inflation. To some extent, higher raw material costs offsets the lower export prices. Recently, the Bank of England deputy governor, Paul Tucker stated he would be open to a weaker pound, but the benefits of a weaker pound would be lost if inflation expectations rose. (Reuters)

The impact on inflation has been muted because of the negative output gap; but, in the past few years, the inflationary impact of devaluation has often been greater than the Bank of England forecast and was a major factor in explaining the cost push inflation we have seen in recent years.

As a rough rule of thumb, a 10% devaluation may increase prices by 2-3%.

The components of the CPI most effected by a devaluation are (regression coefficient)

- Air travel (-1.29)

- Vegetables (-1.22)

- Gas (-0.71)

- Fuel (-0.54)

- Books (-0.35)

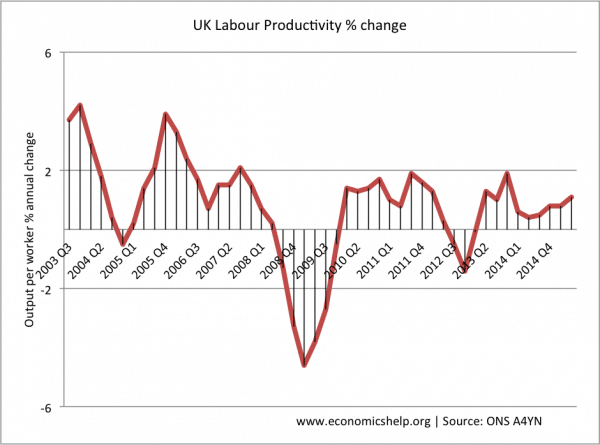

5. Poor Productivity growth

Devaluation only really affects demand. The other side of the equation is supply and productive capacity. The past five years have been very disappointing from the perspective of UK productivity. Devaluation doesn’t necessarily do anything to promote investment and higher productivity. Some even argue that devaluation can reduce the incentive to be efficient because you become competitive without the effort of increasing productivity. Poor productivity could be another factor explaining the current account deficit.

Overall Impact of devaluation

Devaluation 2008-12 had less impact on the economy than we might expect. Devaluation is certainly no magic bullet, which solves the ills of the economy. Part of the reason is that the whole global economy, and Europe in particular, was depressed. In a depressed global environment, the benefits of a devaluation are muted. However, despite the limited impact of devaluation, I believe the economy would be significantly worse, if we were in the Euro and 30% overvalued. If that was the case, we would be struggling to regain competitiveness through internal devaluation – an even deeper recession.

Devaluation of 2016

What about the devaluation of 2016, will this help the UK economy?

In many regards, it may be a repeat of 2008 – a fall in the value of the Pound doing little to help the economy.

- Global growth is weak

- Demand is relatively inelastic

- The pound is falling over uncertainty – e.g. Brexit. This will not encourage manufacturers to invest.

Examples of devaluation

- Leaving the ERM in 1992 – more successful devaluation because it occured during period of high interest rates and high unemployment

- UK devaluation of 1967

Related

Note:

(1) See technical difference between depreciation and devaluation here. I sometimes use devaluation when correct term is depreciation only because in everyday language people tend to talk about devaluations when strictly speaking it is a depreciation.

If firms do not pass on the price reduction made possible via currency depreciation, say by maintaining $ or Euro prices, they will receive more Sterling for their exports. If the demand for such goods is price inelastic, that might be beneficial to UK Balance of Trade.

So any adjustment in output would have to be in import replacing sectors. It takes time and it seems likely that the uncertainty slows down adjustment.

Nobody will add capacity while the outlook is uncertain and exporters may be happy to take higher Sterling margins rather than extra volume.

It depends on how quickly information is received by the parties concerned – the importers and exporters – when more time is taken, even with the devaluation Balance of trade would worsen. The situation will gradually improve as seen from the j curve effect. However, if the rate of inflation rises, than those of its competitors, a country will not be able to manage its competitiveness in the international front, and export revenue is likely to fall and imports show a rising trend. This would deteriorate the current account balance. Therefore devaluation should be exercised with great care.

Isn’t a further problem that the UK has lost a lot of exporting companies – particularly during the Thatcher years – so whilst the devaluation of sterling should give us an advantage we no longer of the goods to sell?

To some extent. Certainly manufacturing output fell considerably in the early 1980s, but the UK has some significant manufacturing industries still e.g. car industry is doing well.

https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/7164/trade/importance-of-exports-to-the-economy/

https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/7132/economics/uk-production/