Definition of a liquidity trap: When monetary policy becomes ineffective because, despite zero/very low-interest rates, people want to hold cash rather than spend or buy illiquid assets.

A liquidity trap is characterised by

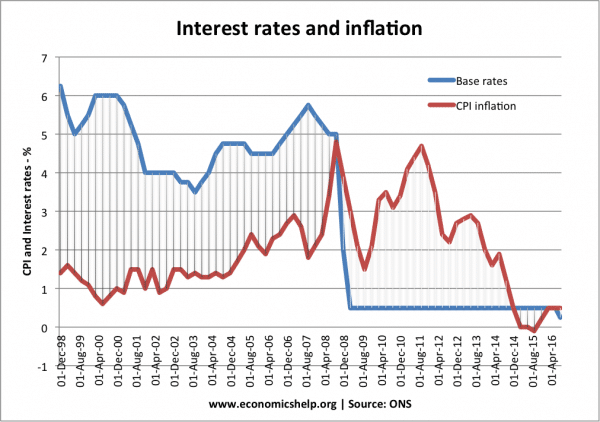

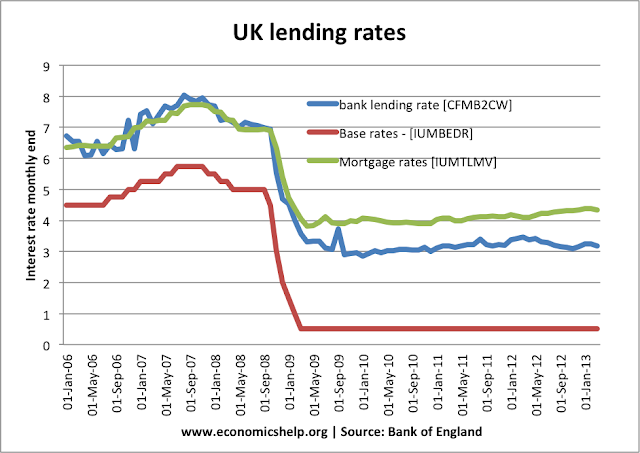

- Very low-interest rates

- Low inflation

- Slow/negative economic growth

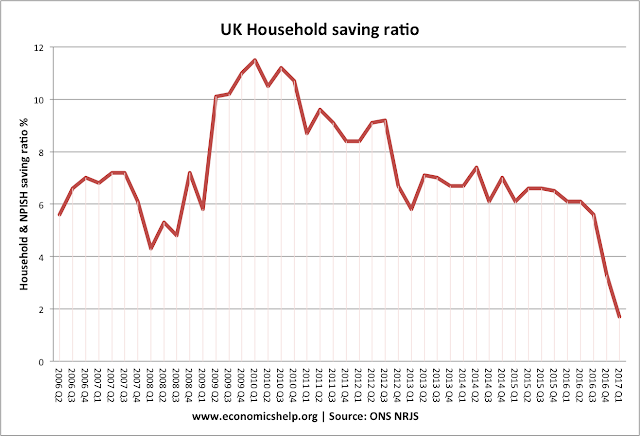

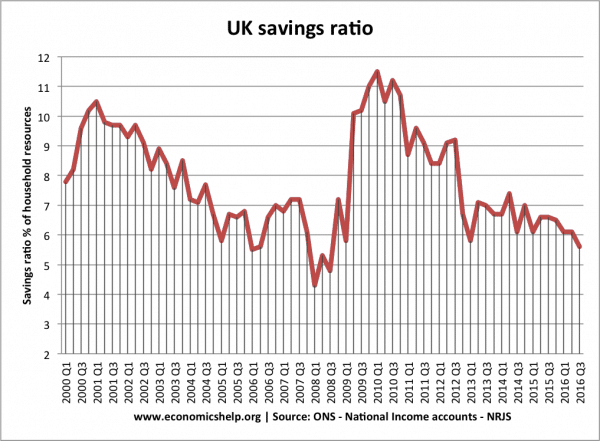

- Preference for saving rather than spending and investment

- Monetary policy becomes ineffective in boosting demand

Solutions to a liquidity trap

- Keynesians argue in a liquidity trap, we need to use expansionary fiscal policy

- Modern Monetary Theorist argues we should target a higher inflation rate, increase inflation expectations and increase the money supply – putting cash into households hands directly if necessary.

- Monetarists argue Central Banks should use quantitative easing to increase the money supply, and if necessary purchase bonds and assets to reduce yields on corporate and government bonds.

Examples of liquidity traps

- Great Depression 1929-33

- Japan in the 1990s and early 2000s

- UK, EU, US – 2009-15. (US economy started to raise rates before UK/EU)

The liquidity trap of 2009-15

In the post-war period, there was no incidence of a liquidity trap in western economies (outside Japan). However, in 2008, the global credit crunch caused widespread financial disruption, a fall in the money supply and serious economic recession. Interest rates in Europe, the US and UK all fell to 0.5% – but the interest rate cuts were ineffective in causing economic activity to return to normal.

Example: Cut in interest rates in early 2009, failed to revive the economy.

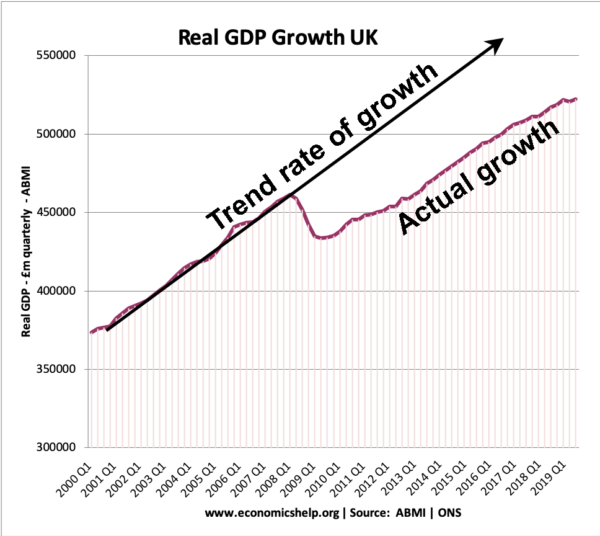

From 2009, economic growth in the UK was below the trend rate of economic growth – leading to lost real GDP.

From 2009, economic growth in the UK was below the trend rate of economic growth – leading to lost real GDP.

Money Supply Growth in a Liquidity Trap

A feature of a liquidity trap is that increasing the money supply has little effect on boosting demand. One reason is that increasing the money supply has no effect on reducing interest rates.

When interest rates are 0.5% and there is a further increase in the money supply, the demand for holding money in cash rather than investing in bonds is perfectly elastic.

This means that efforts to increase the money supply in a liquidity trap fail to stimulate economic activity because people just save more cash reserves. It is said to be like ‘pushing on a piece of string’

Quantitative easing in the Liquidity trap of 2009-15

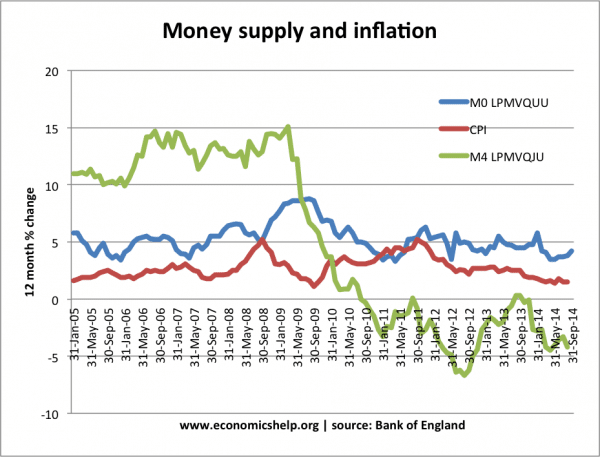

In the liquidity trap of 2009-15, there was a large increase in the monetary base (due to Quantitative easing) but the broad money supply (M4) showed little increase.

MO (monetary base) increased by over 7% in 2009 – but, it couldn’t stop the decline in M4.

Why do Liquidity Traps Occur?

Liquidity traps occur when there is a decline in economic activity, low confidence and unwilling by firms to invest. In more details

- Balance sheet recession. In a balance sheet recession, firms and consumers have high levels of debt and the recession creates an incentive for them to pay off debt (and cut back on borrowing). Whatever happens to interest rates, firms do not want to borrow – they want to pay off their debts so there is little appetite for higher spending.

- Preference for saving. Liquidity traps occur during periods of recessions and a gloomy economic outlook. Consumers, firms and banks are pessimistic about the future, so they look to increase their precautionary savings and it is difficult to get them to spend. This rise in the savings ratio means spending falls. Also, in recessions banks are much more reluctant to lend. Also, cutting the base rate to 0% may not translate into lower commercial bank lending rates as banks just don’t want to lend.

At the start of the credit crunch, there was a sharp rise in the UK saving ratio.

- Inelastic demand for investment. In a liquidity trap, firms are not tempted by lower interest rates. Usually, lower interest rates make it more profitable to borrow and invest. However, in a recession, firms don’t want to invest because they expect low demand. Therefore, even though it may be cheap to borrow – they don’t want to risk making investment.

- Deflation and high real interest rates. If there is deflation, then real interest rates can be quite high even if nominal interest rates are zero. – If prices are falling 2% a year, then keeping cash under your mattress means your money will increase in value. Deflation also increases the real value of debt

- In the US, the Great Depression, the inflation rate between 1929 and 1933, was –6.7 percent. (link)

- In Japan, deflation occurred between 1995 and 2005 (average deflation rate of -0.2%

- Bank closures/Credit Crunch. In 2008 banks lost significant sums of money in buying sub-prime debt which defaulted. Then they became reluctant to lend. In the early 1930s

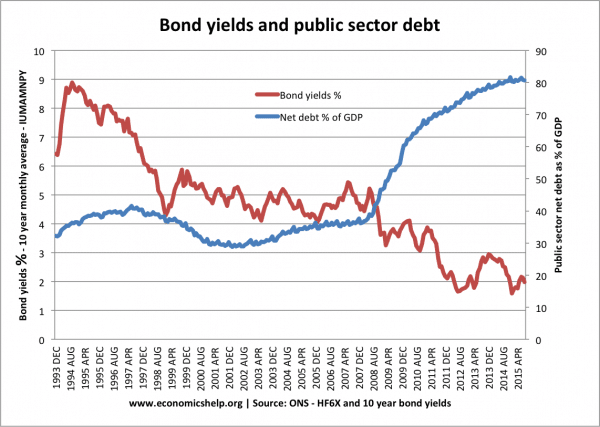

- Unwillingness to hold bonds. If interest rates are zero, investors will expect interest rates to rise sometime. If interest rates rise, the price of bonds falls (see: inverse relationship between bond yields and bond prices) Therefore, investors would rather keep cash savings than hold bonds.

- Banks don’t pass base rate cuts onto consumers

In a liquidity trap, commercial banks may not pass base rate onto consumers.

- Low productivity growth. In a period of low productivity growth, firms may have less incentive to invest

- Demographic changes. An ageing population may shift the economy to a more conservative saving economy – rather than spending and investment. This has been put forward as a possible factor in the secular stagnation of recent years.

Keynes on a liquidity trap

In 1936, Keynes wrote about a potential liquidity trap in his General Theory of Money

“There is the possibility…that, after the rate of interest has fallen to a certain level, liquidity-preference may become virtually absolute in the sense that almost everyone prefers cash to holding a debt which yields so low a rate of interest. In this event the monetary authority would have lost effective control over the rate of interest.”

The importance to Keynes was that if cutting interest rates wasn’t an option, the economy needed something else to get out of recession. His solution was fiscal policy. The government should borrow from the private sector (from surplus private sector savings) and then spend to kickstart the economy.

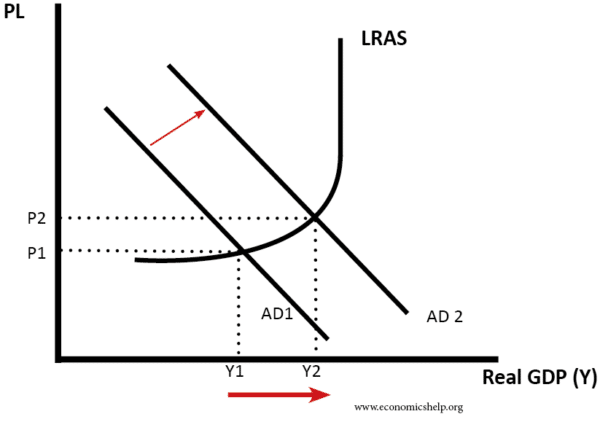

The argument is that the rise in private sector saving (which occurs in liquidity trap) needs to be offset by a rise in public borrowing. Thus government intervention can make use of the rise in private saving and inject spending into the economy. This government spending increases aggregate demand and leads to higher economic growth

Fiscal policy and crowding out

Monetarists are more critical of fiscal policy. They argue that government borrowing merely shifts resources from the private sector to the public sector and doesn’t increase overall economic activity. They argue the increase in government borrowing will push up interest rates and crowd out private sector investment. They point to the experience of Japan in the 1990s where a liquidity trap was not solved by government borrowing and a ballooning public sector debt.

Idle resources and crowding in

This shows the rapid rise in private sector saving in 2008/09.

Keynesians respond by saying, government borrowing may well cause crowding out in normal circumstances. But, in a liquidity trap, the excess rise in savings means that government borrowing won’t crowd out the private sector because the private sector resources are not being invested, but just saved. Resources are effectively idle. By stimulating economic activity the government can encourage the private sector to start investing and spending again (hence the idea of ‘crowding in’)

Also, Keynesians say that as well as expansionary fiscal policy, it is essential that governments / monetary authorities make a commitment to inflation. If expansionary fiscal policy occurs during periods of deflation it is likely to fail to boost overall aggregate demand. It is only when people expect a period of moderate inflation that real interest rates fall and the fiscal policy will be effective in boosting spending.

Modern Monetary Theory

Modern monetary theory (MMT) argues that in a liquidity trap, the expansionary fiscal policy can be financed by an increase in the money supply and government borrowing is not needed. As long as inflation remains within an acceptable target, the government can print money to finance the spending.

Criticism of the liquidity trap

Austrian economists. Ludwig Von Mises was critical of Keynes’ concept of a liquidity trap. He argued a fall in investment was caused by issues such as poor investment decisions, decline in productivity of investment and the business/productivity cycle.

Policies to overcome a liquidity trap

- Quantitative Easing – policy to create money and reduce yields on government and corporate bonds

- Helicopter money – more direct than quantitative easing as rather than buying assets from banks, the money is given directly to the people.

- Expansionary Fiscal Policy – Keynes argued in a liquidity trap, it is necessary for a government to pursue direct investment in the economy. For example, building public work schemes has the effect of creating demand and getting unused resources back into the circular flow.

Related

I’ve taken an interest in economics for forty years, and I’m sick to the back teeth of the Keynes versus monetarist argument. I suggest that when we want to stimulate our economy we go for a policy which involves both Keynsian and monetarist elements, i.e. a budget deficit which is not matched either by increased tax or government borrowing. This constitutes money printing, which is what has happened in 2009 in the guise of “Quantitative easing”.

This policy is monetarist in that it increases the money supply. It is Keynsian in that it constitutes and injection, very much like an increase in exports. Whether it’s the money supply increase that does the real work or the Keynsian injection – well who cares as long as it works? Conversely, when we want to dampen economic activity with a view to controlling inflation we could (as well as raising interest rates) implement a budget surplus unmatched by tax or borrowing reductions. This equals “money extinguishing”.

Since the clowns who got us into this mess are “still” being rewarded (banks by hoarding reserves and by not being forced into bankruptcy) and the 0% down/no doc homeowners (who are allowed to stay in their homes without paying anything for up to 3 years), we have stagnation. Because banks are not releasing (or are slowly releasing) houses back onto the market, prices are being propped up artificially. This benefits the banks who don’t have to mark to market, and the homeowners.

Helloooooo!!!! How about trying something different. How about rewarding the people who didn’t take ridiculous risks because they knew the bubble was going to burst eventually? Why not raise interest rates for the savers (who didn’t partake in the merriment). This would force the homeowners out (who shouldn’t ever have been there in the first place), and would force the banks who took ridiculous risks out, making room for new banks who are fiscally prudent to come in.

The savers, after receiving interest on their money, would begin to feel safer, and would begin to invest their hard-saved money.

You’re trying to help the wrong people. The ones who would invest wisely are the savers (the ones who are being penalized right now).

The idiots need to be weeded out. If you want a flower to grow, get rid of the weeds.

liquidity trap

over-decrease in interest rate = over-decrease in investment or over-increase in saving

What type of fiscal and monetary policy is effective in case of a developing country in order to improve their GDP?