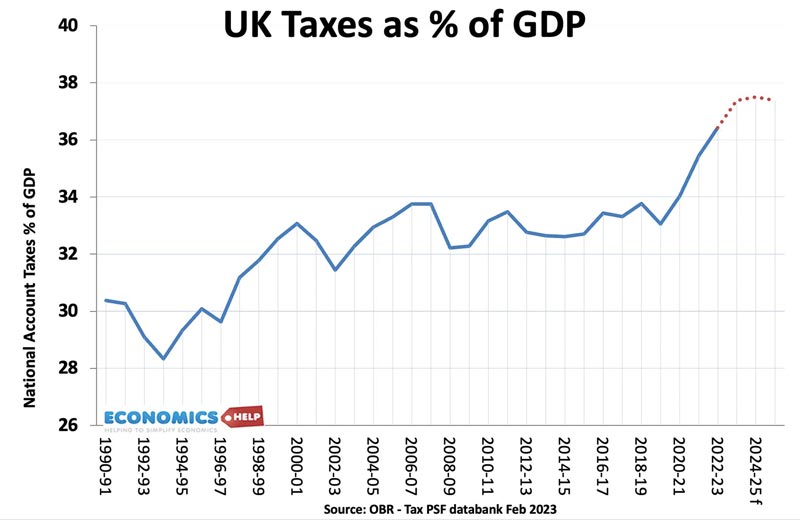

The UK tax burden is rising to the highest level since the Second World War. The IFS stated it will be a record-breaking parliament for tax rises. The only chancellor to actually cut taxes was Kwasi Kwarteng, whose bold, unfunded tax cuts, led to higher bond yields and a fall in sterling. But, if no one likes higher taxes, why are taxes rising so much? And do failing public services, a stagnant economy and ageing population mean the only alternative will be even higher taxes in the future?

In 2010, taxes were 33% of GDP. Now taxes are 37% of GDP, this is an average of £3,500 more per household than if the tax burden had stayed the same. Yet, there are seven reasons why permanently higher taxes are likely to stay.

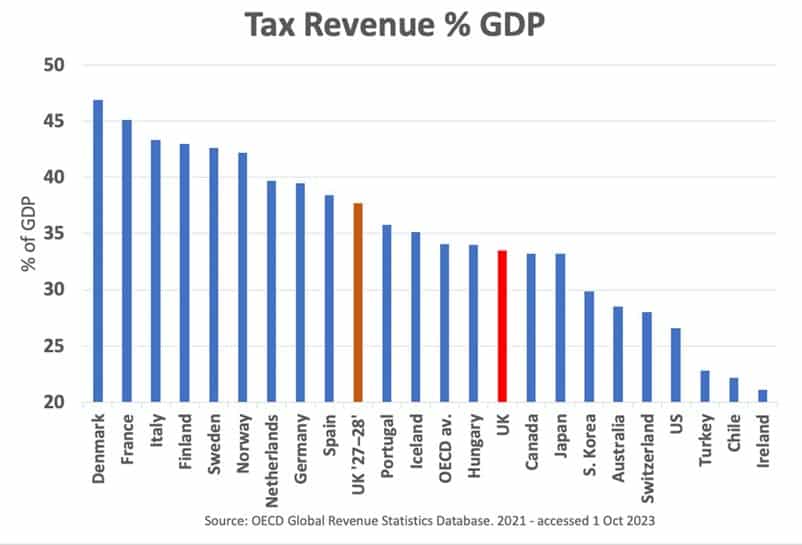

Firstly, the UK tax burden is not particularly high by international standards. The tax burden is lower than many European countries, though it is forecast to catch up by 2028. Interestingly back in the 1960s, the UK was relatively high tax. But since then has been overtaken by European countries, especially Scandinavian countries. An interesting question to look at is whether that model of high tax, and high spending could be future for the UK. Or is there a chance to emulate Ireland?, which in recent years has grown much faster than the UK.

In the early 2010s, the UK tax burden was kept low, partly through the austerity of the Osborne and Cameron era. But, now with the multiple costs of Covid, Brexit, ageing population and the energy crisis, taxes are catching up.

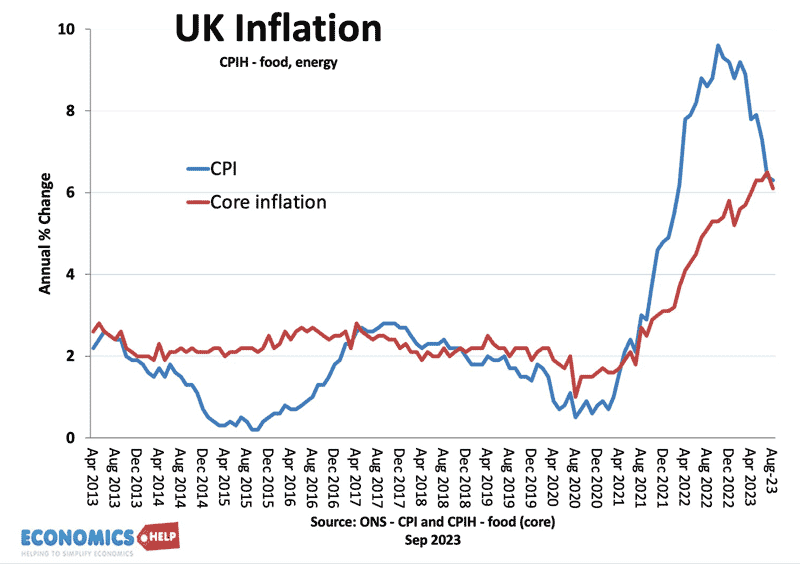

Secondly, A significant portion of the recent tax burden is due to recent inflation. Wage inflation has led to stealth tax rises for millions of households who have entered into the higher tax brackets – This is known as bracket creep and will net the treasury an extra £40 billion – more than initially planned. But, whilst nominal wages rise, high inflation means real incomes have stagnated.

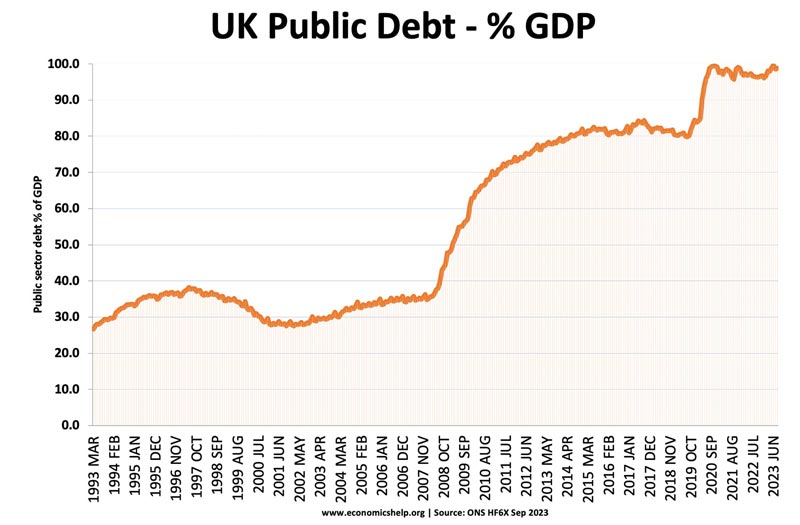

Thirdly, there has been a deterioration in public finances, with steadily rising debt as a share of GDP from 40% to 100% of GDP. Furthermore, another cost of inflation has been a surge in government debt interest payments. The UK sold many index-linked bonds, which means with higher inflation, the government has to pay higher debt interest payments. The rise in government debt, higher debt interest payments, and the government’s own fiscal rules means there is very limited scope to cut taxes, even if a chancellor wanted to.

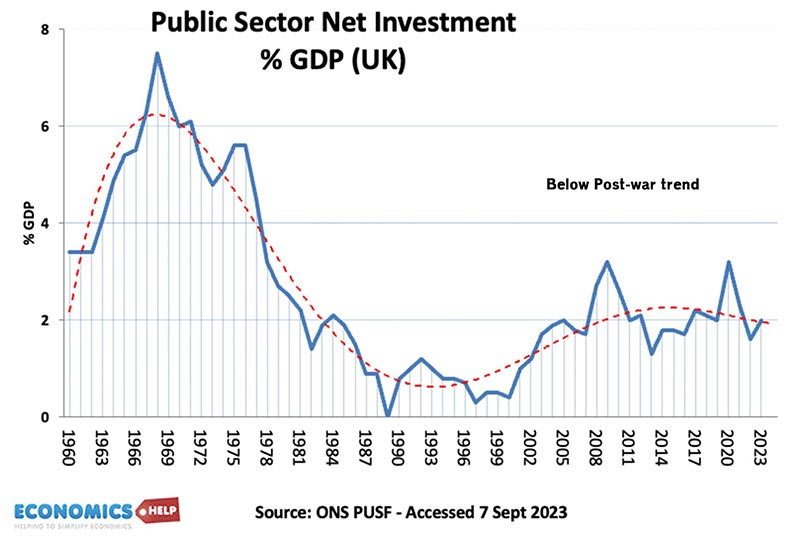

This was the downfall of Truss and Kwarteng, if they had cut taxes in 2010 when interest rates and inflation were close to zero, they would not have been an adverse bond market reaction. But, in 2022, high inflation and interest rates, means unfunded tax cuts are much more risky because the cost of borrowing is higher and markets dislike the inflationary impact of tax cuts. The chancellor Jeremy Hunt, recently stated he would like to cut taxes, but to do so would be inflationary. This is the dilemma. Because of stubbornly high inflation, the Bank of England have been raising interest rates. If the chancellor did cut taxes which led to higher spending, the Bank would be inclined to raise interest rates even further. What you give with one hand would be taken away by the other.Fourthly years of austerity and underinvestment in public services have caused a backlog of capital investment and long-waiting lists. The concrete crisis which caused schools to be closed down at the start of the year is emblematic of this. When you have cut investment for so many years, it becomes expensive to repair crumbling infrastructure. You could say austerity is increasingly expensive. Even when the UK has managed to start public investment, it doesn’t have a great record. The cost of HS2 has ballooned due to inflation and the additional costs of building tunnels e.t.c. to appease local constituencies.

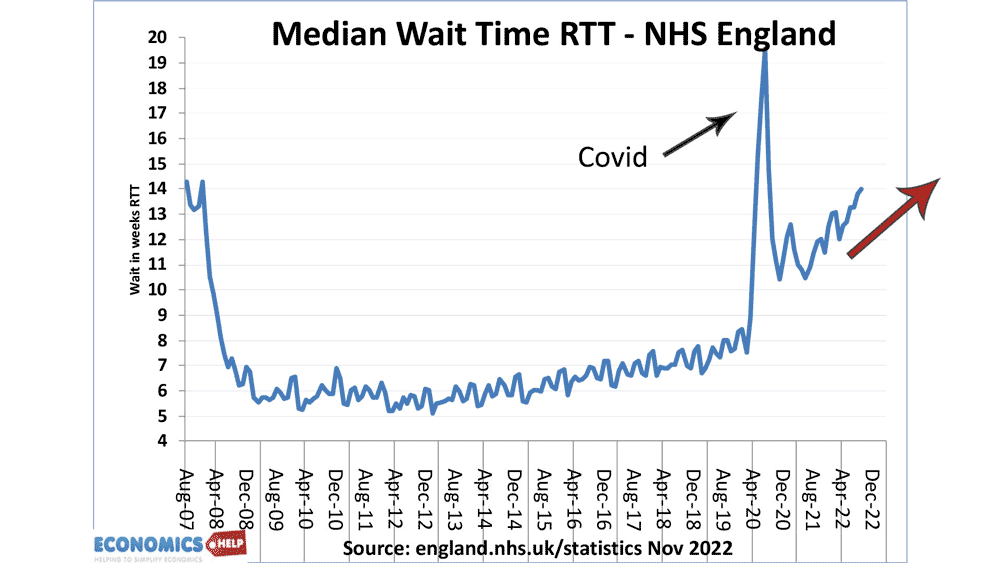

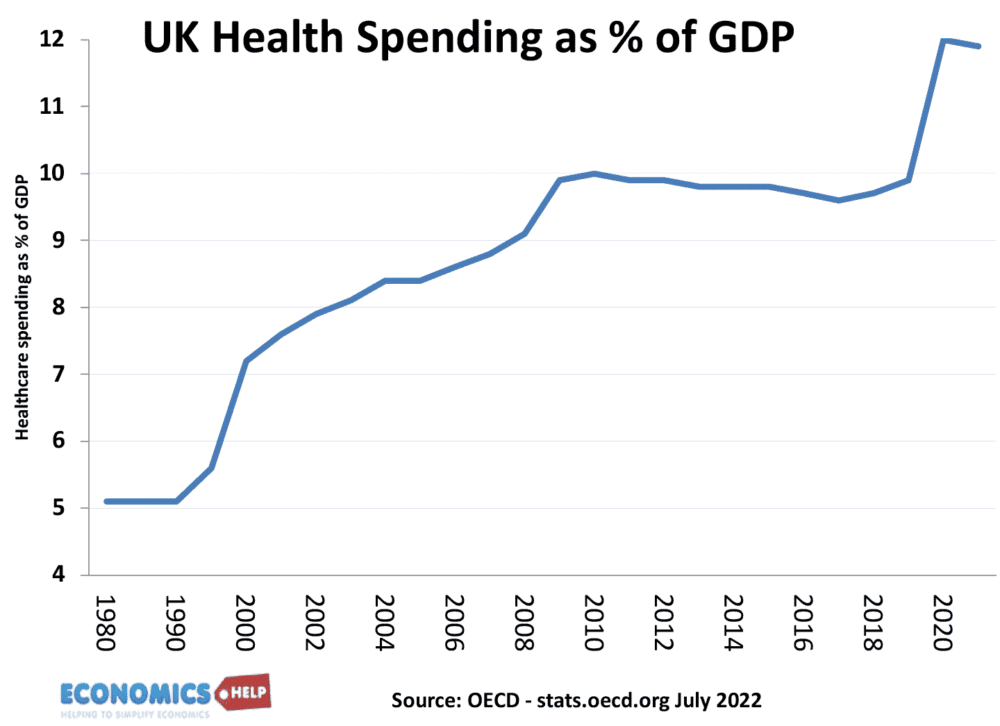

Fifthly, whilst UK voters want lower taxes, we also expect better standards of health care. In recent years, exacerbated by Covid, there has been a sharp rise in waiting lists. The crisis in the NHS is visible, we have all had experiences of either ourselves or knowing a relative struggling to get an appointment or a nightmare 24-hour wait in A&E. The problem is that there is unlikely to be any let up in spending pressures on the NHS. We have an ageing population who require relatively more health care, but also new, more expensive treatments. Healthcare spending as a share of GDP has risen from 5% in 1990 to 12% in 2021.

Real spending per person has tripled in just 30 years. With total public health spending of £233.1 billion, it is unsurprising there is pressure to raise taxes. In the post-war period, to some extent, we paid for more health care, by reducing defense spending. But, easy gains from cutting military spending are over, with some feeling it is time to actually increase spending in light of recent events.

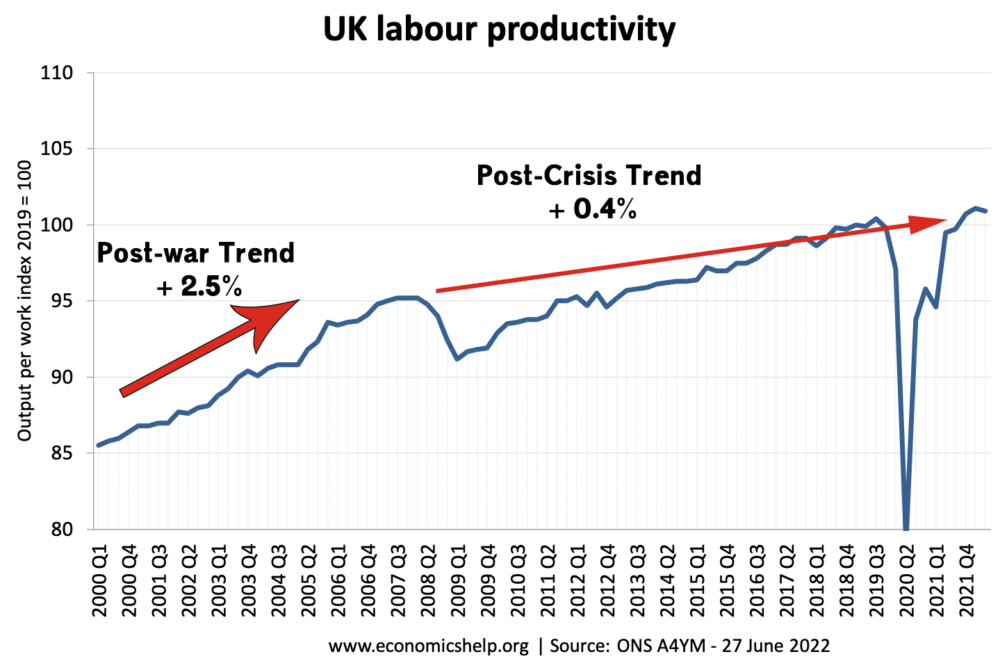

The other canary in the coal mine is that the UK economy has slowed down. The post-war trend rate of growth was roughly 2.5%. This enabled higher public spending without raising tax rates. But, since 2010, productivity growth has slowed down quite sharply.

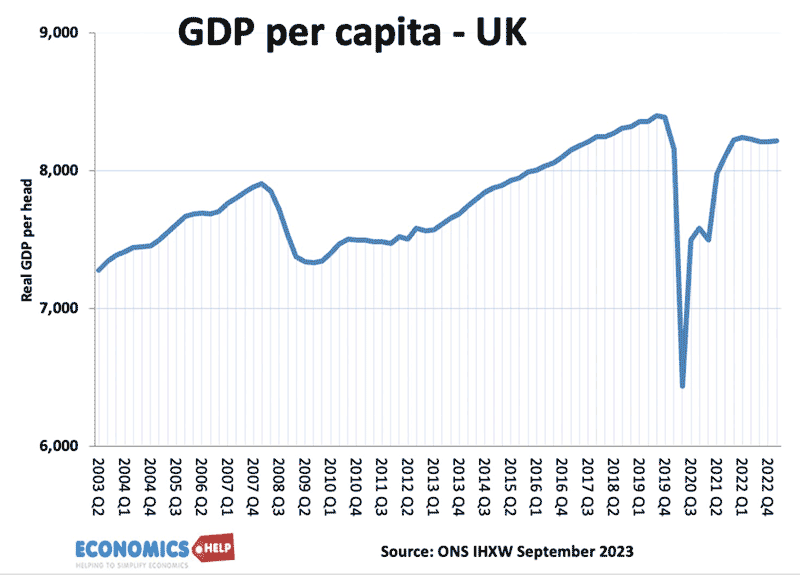

This is GDP per capita in the UK. it does include recent upward revisions to GDP which as you can see doesn’t change the overall picture of under-performance. This is very important for the future of tax. If growth continues to be weak, the only way to pay for higher health and pension spending is higher taxes. It is a conversation which is not very popular. Politicians like to make vague promises of increasing growth, but actually increasing growth has proved elusive.

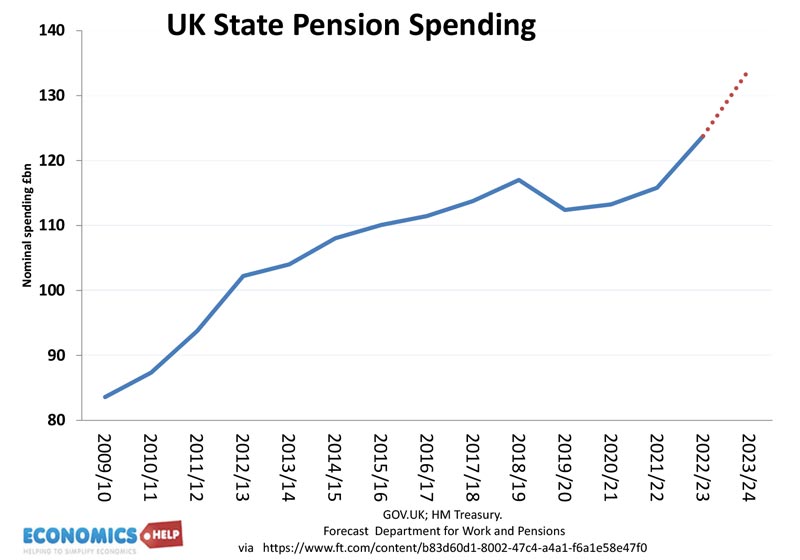

Related to health spending is rising pension spending. In a time of inflation, the triple lock guarantee is quite expensive with an extra £10 billion this year. With political parties reluctant to anger a big voting block, the only option is to increase the retirement age or increase taxes. Another problem, is the rise in long-term sickness in the UK. Under current trends, the OBR expect health and disability benefits to soar to £80bn.

This is the problem governments face, there is very strong upward pressure on spending from health, welfare and pension spending. But, this spending is like maintenance spending – just keeping up with demand, if you wanted to reduce welfare spending and revitalise areas of a depressed economy, it would require even more spending on top.

And there’s even more bad news. Traditional tax receipts are scheduled to fall. Smoking rates are falling, and as people switch to electric cars, petrol receipts will continue to fall. There will need to be new taxes to replace them. Also in the past, UK receipts were boosted by privatisation receipts, North Sea oil revenues and even profit from QE. But, all this is coming to an end with nothing left to privatise and North Sea oil on its way out. Even the government’s budget forecasts for coming years include very optimistic cuts to spending patterns. The problems after years of austerity, there is little fat to trim, with local councils in Surrey and Birmingham facing real financial crisis.

Taxes under Labour?

So far the Labour party have been fairly conservative about spending. Plans for capital investment of around £25bn a year will actually do little to prevent a decline in capital spending as a share of GDP. Public investment is one area where the government could finance by borrowing rather than spending. There is an economic case for borrowing to invest as in theory, it can lead to higher growth and fewer costs of maintenance. But, in today’s political climate, the virtues of borrowing for investment are fairly weak.

What about the prospects of labour government? In recent months, the Labour party have only planned fairly modest tax changes. They have ruled out wealth tax and higher top tax rate. But, if they win the next election they will inherit this very tricky set of circumstances, ever-rising public spending and expectations they will be able to do something different. They may not want to raise taxes, but if current trends continue, they will face very awkward decisions. The question we need to ask is would it be such a bad thing if taxes rose. We have to make a choice. Scandinavia or US model. But, you can’t have European-style health care on US taxes. Some argue we should look to the example of Ireland who has only 22% of GDP in tax. In recent years, they have accelerated past the UK, and it’s more than just multinationals inflating GDP stats.

Related