Thatcher introduced a break with the post-war consensus introducing new economic ideas such as

- Monetarism

- Free-market supply side policies

- Privatisation

- Tax cuts (especially for high income earners)

- Reduced power of trade unions.

The impact was far ranging.

The 1970s Economy

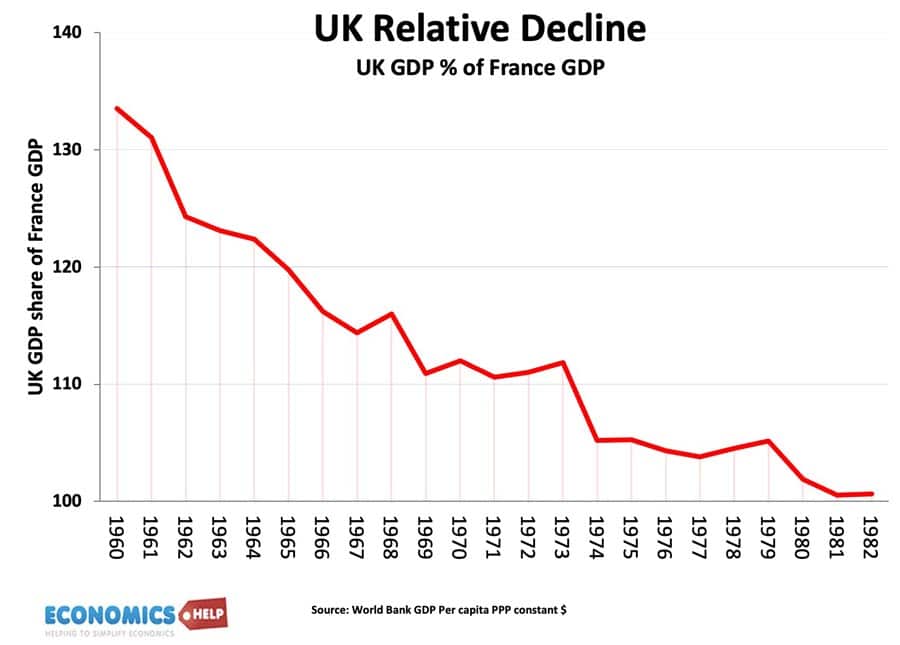

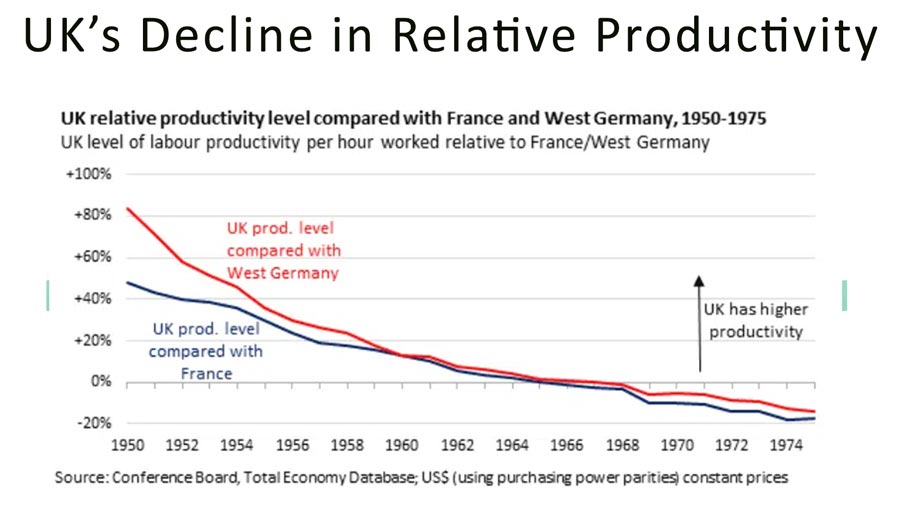

The 1970s was a decade of rampant inflation, industrial strikes and economic stagnation. The Pound was declining fast and the UK economy was falling behind its competitors. There was a general sense something needed to change, and Thatcher was ready with radical free-market policies. Monetarism, privatisation, shrinking the state. The post-war consensus was over.

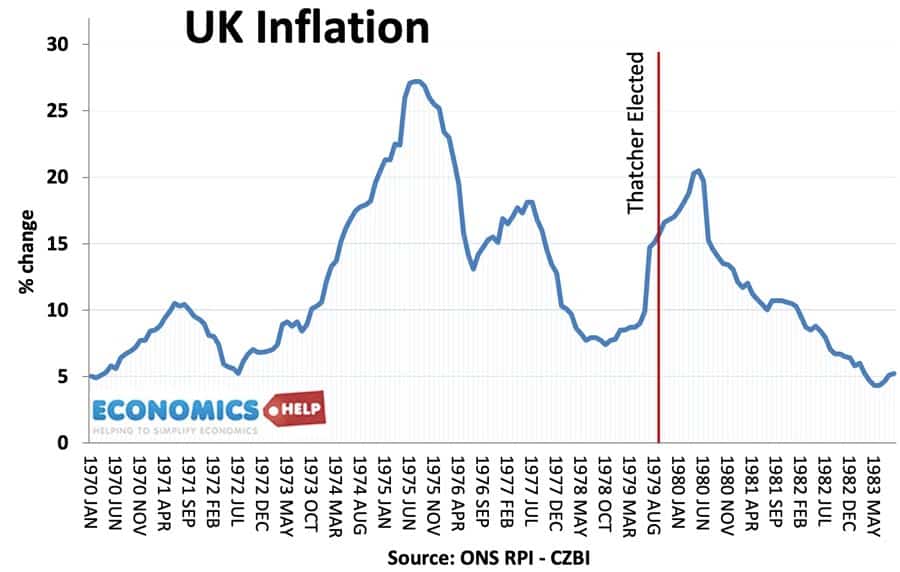

Dealing with Inflation

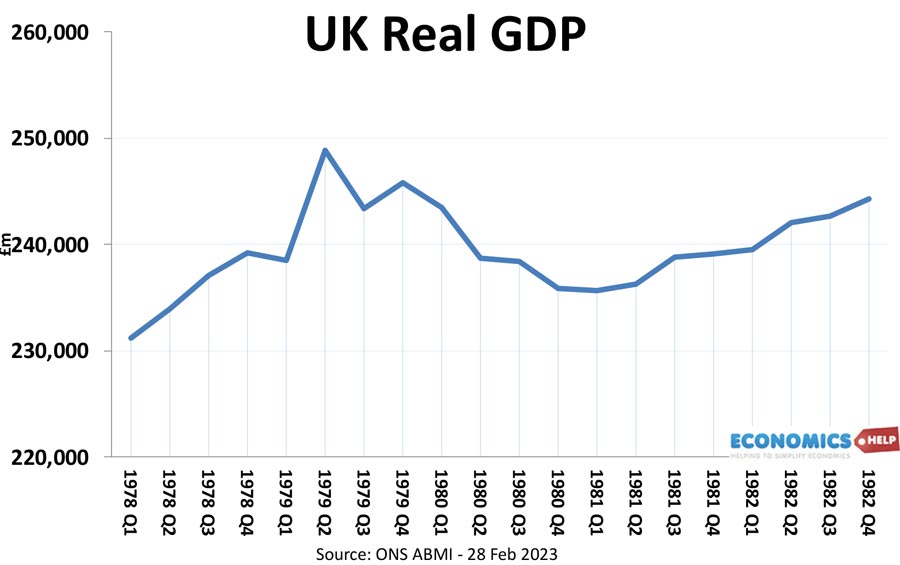

Thatcher’s first task was to reduce inflation. Interest rates were increased and government spending cut. The economy went into recession, but inflation continued to rise. Thatcher just doubled down, putting up more taxes, and increasing interest rates. A disciple of monetarism, she was determined to squeeze the money supply until inflation fell.

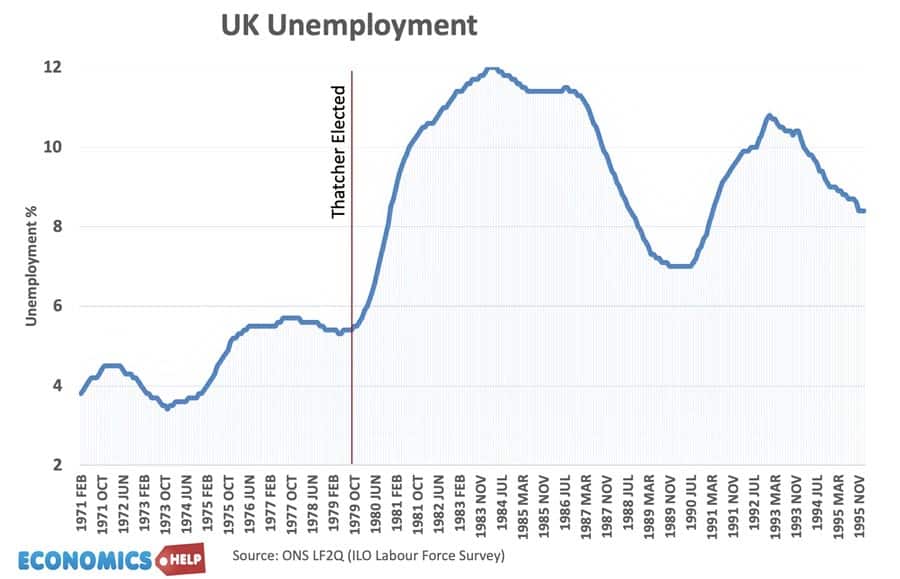

The result was predictably a deeper recession and a surge in unemployment. Unemployment rose to the highest level since the great depression.

But, in the inner cities and industrial north, it was even worse, Youth unemployment soared, contributing to the wave of riots which spread across British cities in the summer of 1981.

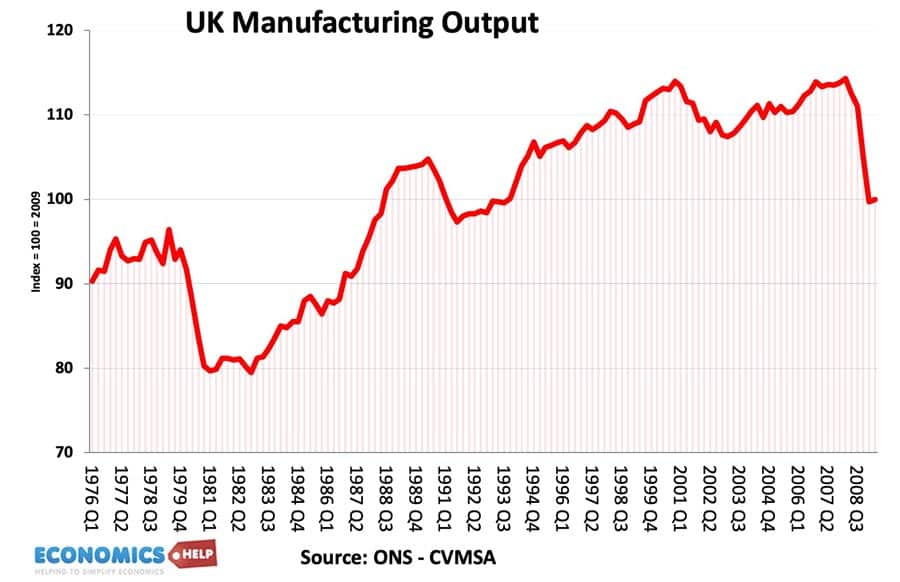

Manufacturing output fell 20%. 364 Economists wrote a letter to the Times claiming there was no basis in economic theory for Thatcher’s approach.

Thatcher wanted to shake up industry, end state subsidies and let failing firms go under, but in the early 1980s, the recession was so deep even efficient firms were going under and despite recovery in the later part of the 1980s, UK manufacturing was never the same, Britain would become a very different economy – dominated by the service and financial sector.

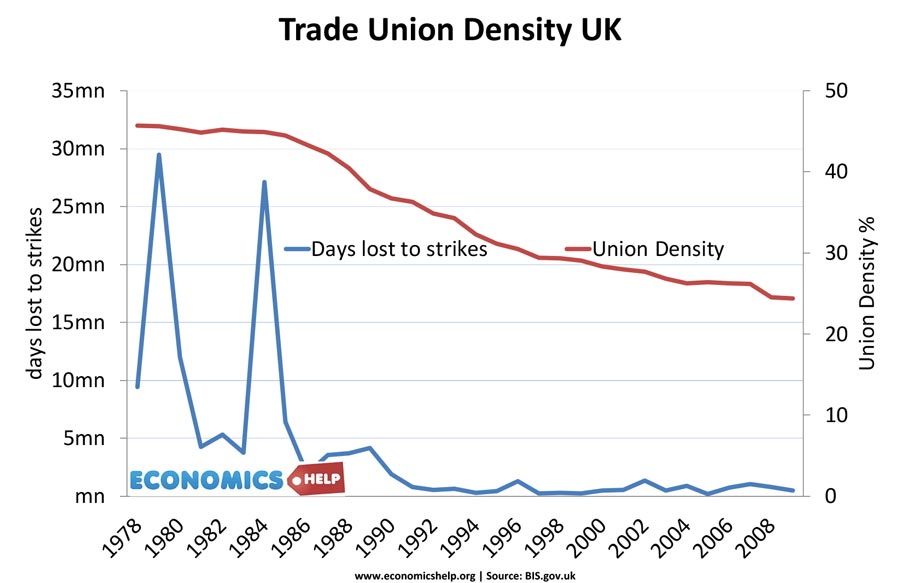

With unemployment hovering over 3 million, Thatcher’s next target was the unions. She had not forgotten the feeling that in the 1970s, it seemed the unions had held the country to ransom. Industrial action and strikes were a major problem for British industry with productivity hit by persistent disputes, poor management and a lack of investment. UK productivity growth was one of the worst in the developed world.

One thing is for certain, through both legislation and economic recession, union influence was massively reduced. After reaching a peak in the late 1970s, union membership fell and never really recovered. Time lost to strikes fell, but the modern labour market has become more fragmented with zero hour contracts and working class areas never regaining the same kind of pride and community spirit.

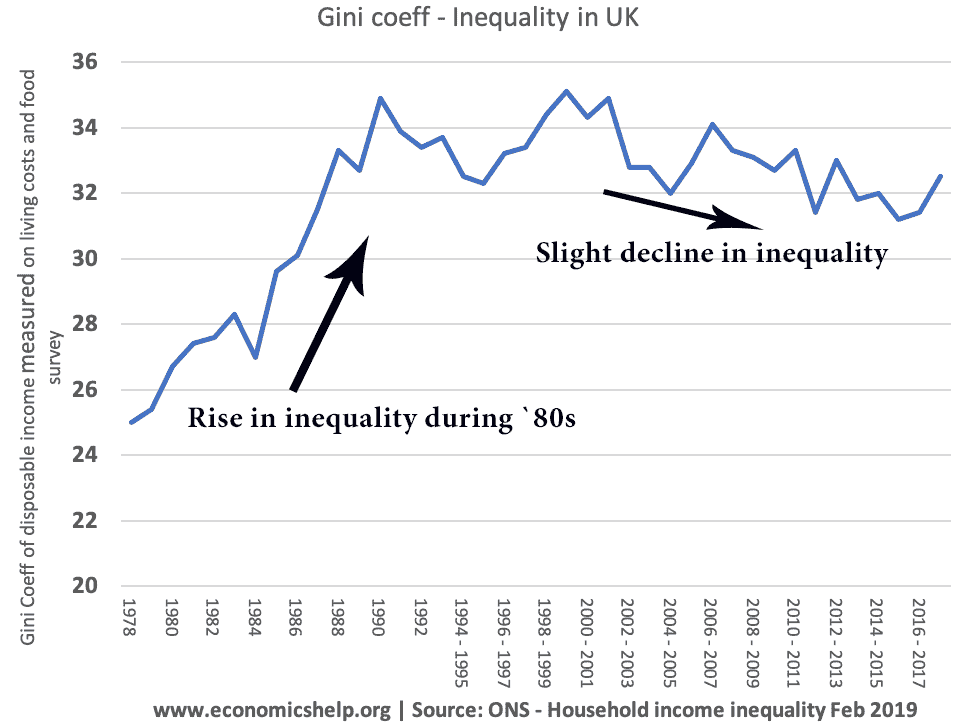

One effect of Thatcher’s economic policy was a 25% rise in income inequality, that has never been reversed, there was also a growing north-south regional divide with former industrial towns, struggling to reinvent themselves.

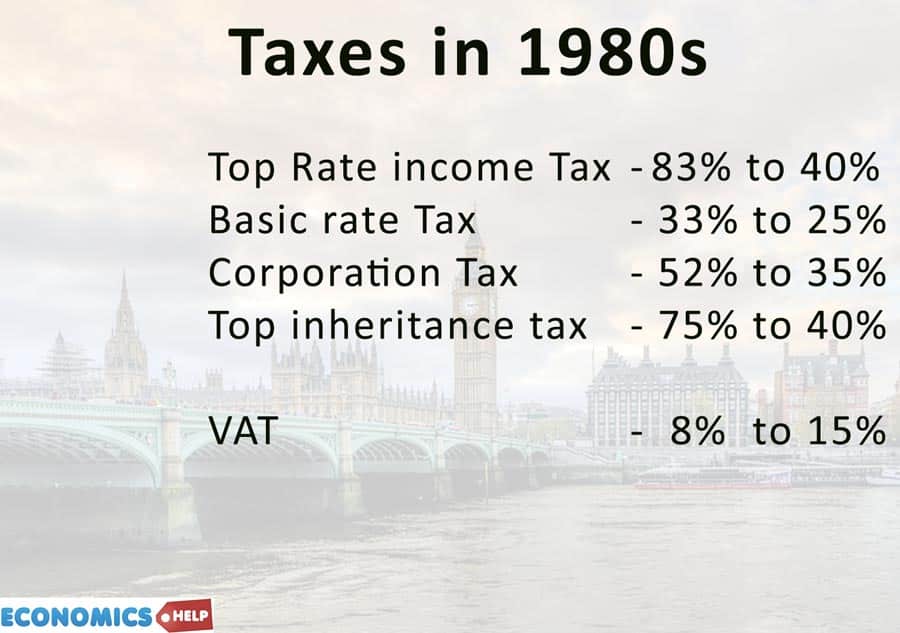

The fact inequality rose under Thatcher is not a surprise, her free-market ideology sought to reward enterprise and reduce the role of the welfare state. Throughout the 1980s, taxes were cut for the high earners and business. Corporation tax fell from 52 to 35%. The highest rate of income tax was cut from 83 to 40%. Though VAT a more regressive tax was doubled. At the other end of the spectrum, low income workers saw a large rise in unemployment and a fall in relative value of benefits.

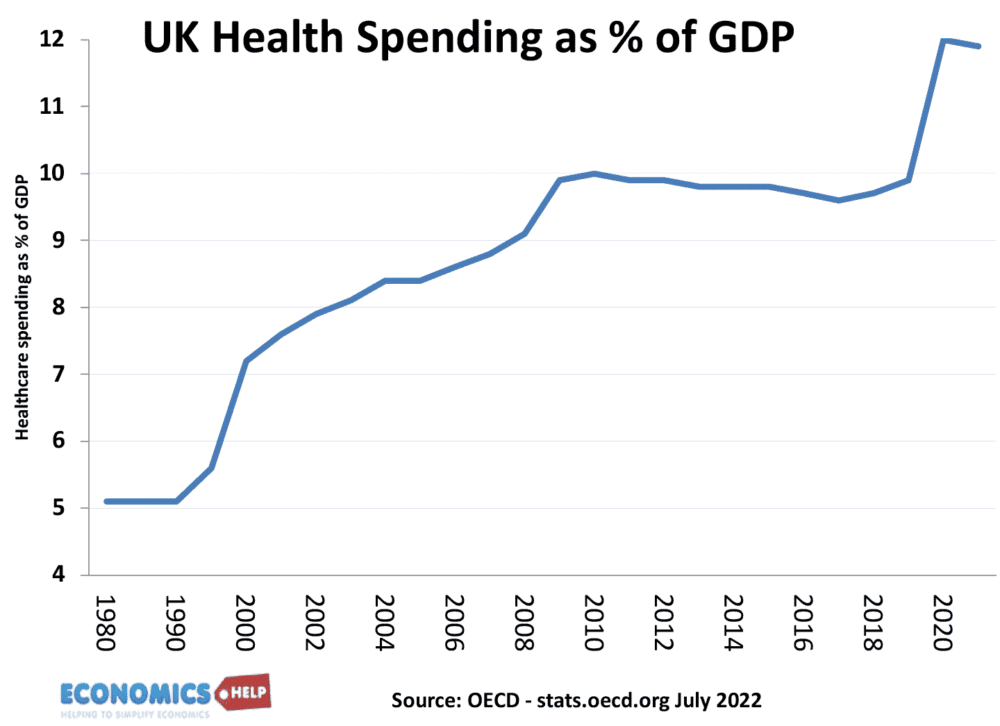

Even healthcare spending was squeezed during the 1980s. Her most controversial tax was replacing local rates with the Poll Tax, using logic that a millionaire should pay the same as a nurse. Such a tax is considered ‘efficient’ in the sense it doesn’t change incentives to work, but with inequality already rising, it was a step too far and led to mass protests and refusal to pay.

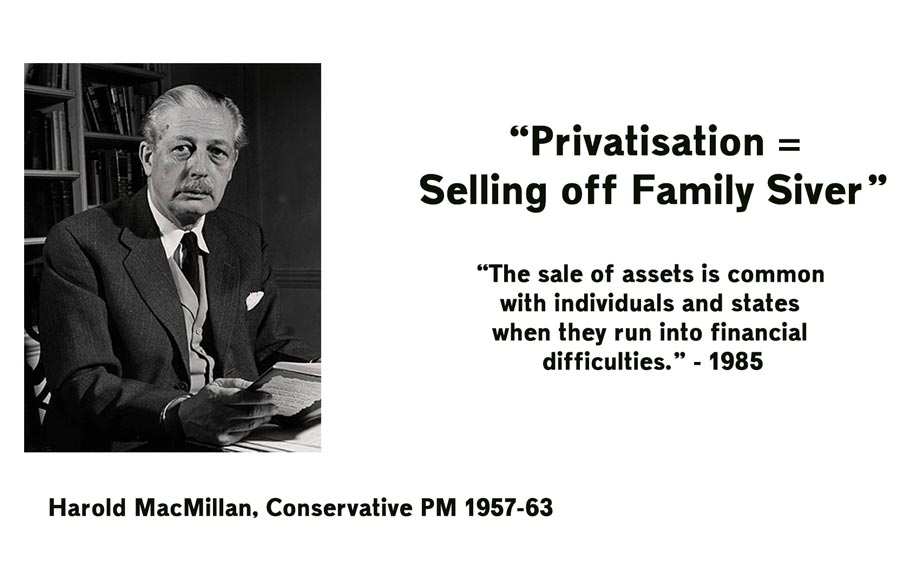

Another flagship policy was privatisation. Throughout the 80s and 90s, the government raised £70bn from privatisation. Harold MacMillan likened it to selling off the family silver. And we could make a sharp contrast between Norway and the UK – both benefitted from a North sea energy bonanza. But Norway retained part ownership and set high taxes investing in a sovereign wealth fund now worth $1.4 trillion, the biggest in the world. But, the UK didn’t take the opportunity to invest. In fact, during the 1980s, public sector investment as a share of GDP declined sharply, with the proceeds of oil being used to fund income tax cuts. It was a short-termism which has become a feature of British economy.

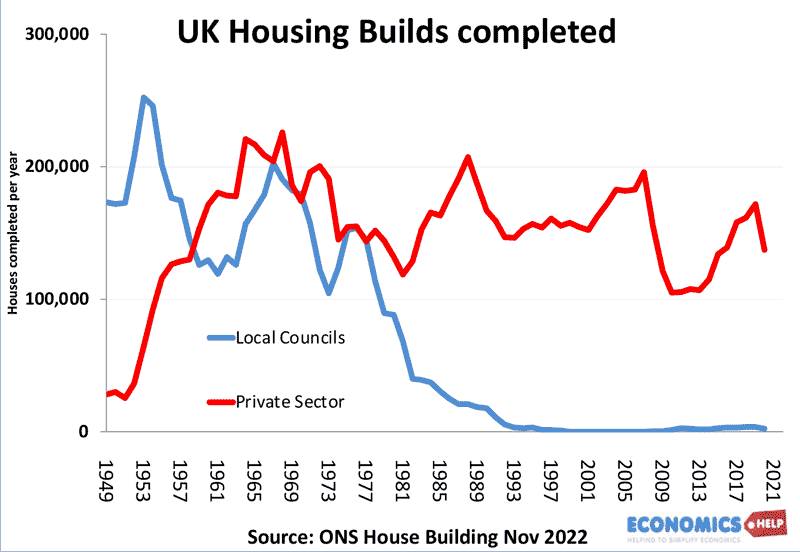

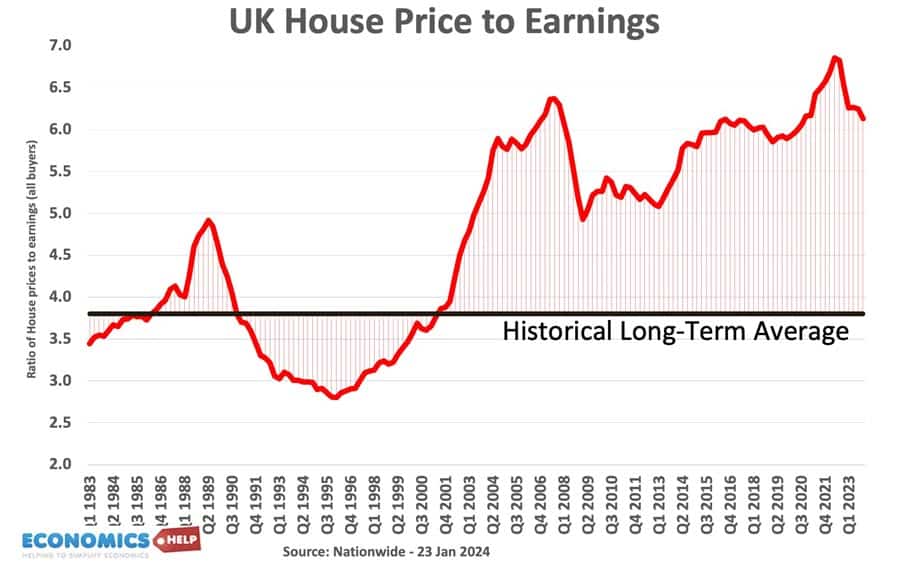

Another significant privatisation was the right to buy council home scheme, over 1.5 million benefited from being able to buy their own property. Home ownership rates soared, and the policy may have been fine if the proceeds had been used to replace the social housing stock with new houses. But, the ideology of the 1980s was to leave it to the free-market. Social housing supply fell and low-income households were left to move into the more expensive private sector. This is real legacy of the 1980s we see today, as housing supply fell behind rising demand, causing housing to reach record levels of unaffordability. The home ownership dream has turned into a nightmare with young people having to save 19 years to get a deposit and house price to income ratios reaching the highest levels since the Victorian age.

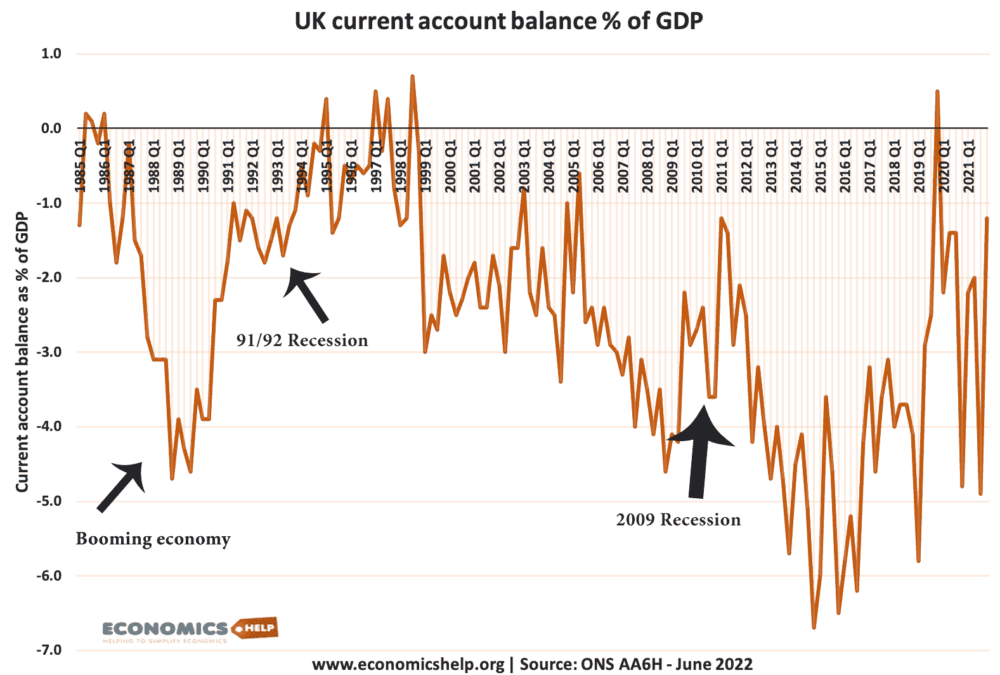

After inflation was tamed through a deep recession, in the late 1980s, the economy started to boom, especially in the south east, House prices soared, and the city of London saw an influx of money, benefitting from financial deregulation. The chancellor talked of an economic miracle, the laggard UK economy turned around by privatisation and supply-side reforms. It was a good story, but unfortunately, the reality was different.

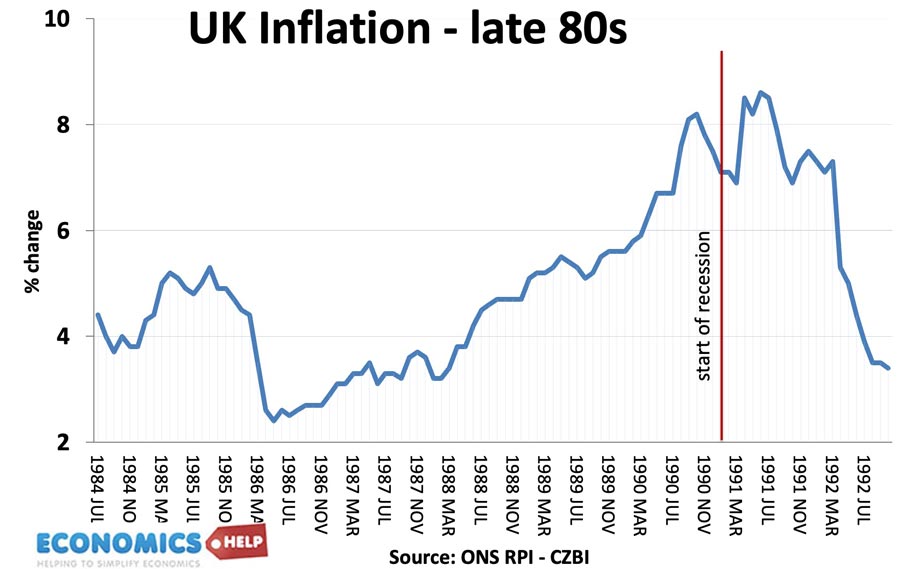

As the economy boomed, inflation crept up, private debt rose, the balance of payments went into deficit.

The UK was living beyond its means. The economy was getting too hot. Despite falling oil prices, inflation increased. There had been no economic miracle, growth rates in the 1980s, were similar to the 1970s. But, by believing their own hyperbole, the economy fell into an inflationary boom, which popped in 1991. The result was a housing crash, negative equity, a deep recession and unemployment rose again. After all the pain of ending inflation in the early 1980s, the return was entirely self-inflicted, with the UK left with the highest inflation rate in the developed world. The failure of the UK chancellor to manage the economy led to the decision in 1997 to grant the Bank of England independence in setting interest rates.

One of the perceived successes of the UK economy in the 1980s, was the growth of the financial sector. The big bang regulation allowed the city to throw off regulatory control and gave them the freedom to dream up new financial instruments such as credit default swaps and the like. The financial sector has become increasingly important to the UK economy and is a major source of income tax revenue. But, the growth of the city, exacerbated regional inequality and means the UK economy is increasingly reliant on London. Outside London, the UK is increasingly a poor country. Although the growth of megacities is a feature of modern economies, it is more pronounced in the UK than elsewhere. Also, there was another long-term consequence.

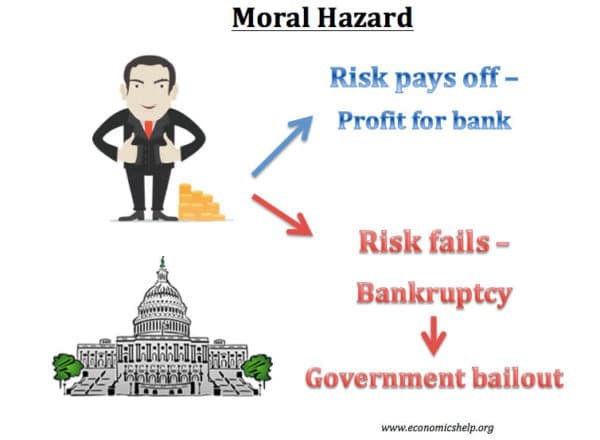

Financial deregulation in both the UK and US led to increased risk taking in the private sector. Former building societies like Northern Rock and Bradford & Bingley took on high risk leveraged lending to maximise profits. But, in 2008, the credit crunch hit their business models and they would have gone bankrupt without government intervention. It highlighted the limits of the free-market. Left to their own devices the finance sector is prone to excessive risk taking and moral hazard. Knowing that if they win, they gain bonuses, but if they lose, the government acts as lender of last resort.

What were the success of Thatcher Economics?

With regard to Europe, Thatcher gained a significant rebate from the EU on the basis that the UK lost out because of the CAP. Thatcher also helped to negotiate Britain’s entry into the Single Market. The reduction of tariffs and barriers to entry provided significant benefits to business and consumers. One study by the Department of Business estimated income gains of 2-6% of GDP per year. Also, Thatcher’s reluctance to join the ERM and scepticism of the Single Currency was borne out by the events of Black Wednesday and the UK’s forced exit from the ERM.

After the pain of the early 1980s, the UK was relatively successful in attracting a new generation of foreign investment, such as Japanese car factories in the north east.

Mixed successes of Thatcher economics

Although Thatcher increased inequality, there was a strong argument that some taxes were too high in the late 1980s. With a marginal rate of 83%, it did cause disincentives to work. The punitive tax rates did harm incentives. Also a corporation tax of 52% would have been very internationally uncompetitive as other countries also cut this tax.

The inflation of the 1970s did need reducing and it was eventually brought under control, however, economists say that a rigid adherence to monetarist targets caused much more economic pain than necessary. In the end, the monetarist experiement was abandoned because the link between money supply and inflation was so weak.

There was definitely a case that industrial relations needed improving both through reforming unions and management. The number of days lost to strikes in the 1970s was unsustainable. However, there was a bitterness about the miner’s strike and lack of empathy with regions devastated by pit closures and industry demand. Sticking to a free-market policies, there was an unwillingness not to do more to protect and support damaged regions and the thousands made unemployment move into new jobs.

I live in Cowley, Oxford near the large car factory which made the old British Leyland Morris Minor and Morris Marina. My next door neighbour who worked there really disliked the perennial strikes as he struggled to feed his family. He claimed the union leaders enjoyed the political fights, but he was left having to grow his own vegetables. He was a big fan of Thatcher because of her union reforms. It was an interesting insight into why Thatcher had considerable support amongst the working classes.

I would put privatisation in the bracket of mixed success. Academic studies give mixed results, with many suggesting ownership makes much less difference than you might imagine. Some industries did benefit from private ownership – primarily those which are not a public good like BT and British Airways. Other industries such as water have been really unsuccessful with private firms putting profit above investment. They increased debt to pay dividends rather than investment. Rather than going from one extreme to another there was third way which sought to combine private enterprise and public ownership. For example, the UK privatised the oil industry 100% and gained much less than say Norway, which retained around 70% ownership.