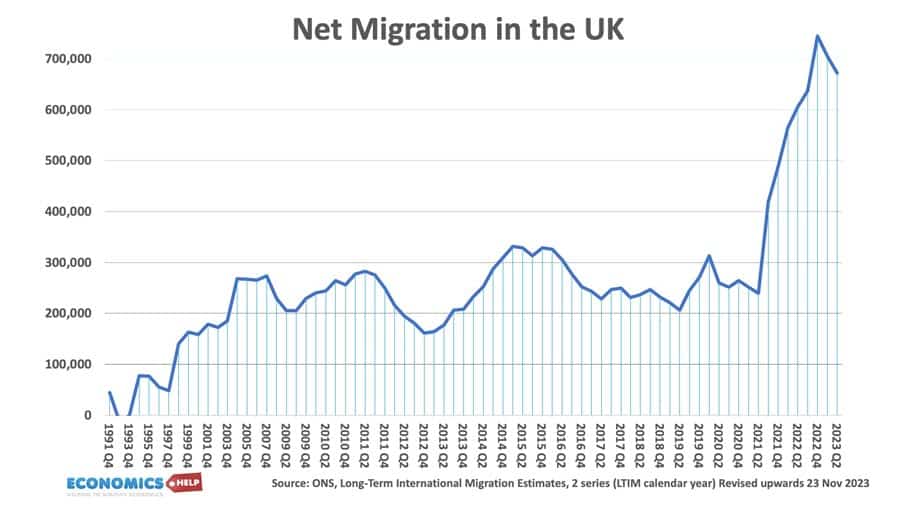

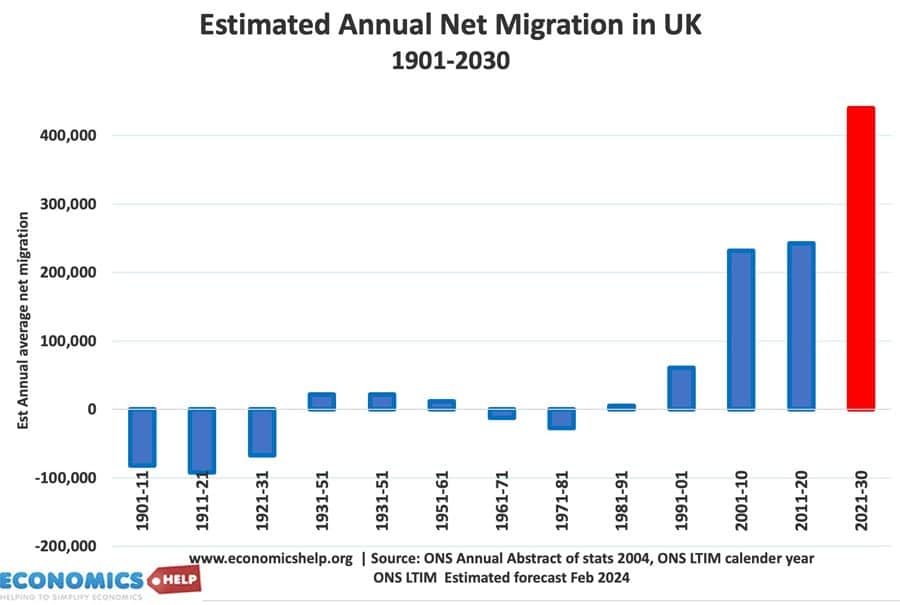

The UK is experiencing record levels of immigration and although it will fall a little in coming years, it will still be a record decade for immigration. The big question is why are immigration levels so high, how will it affect the economy and can the housing market cope with such a rise in the population?

The irony is that while the UK is set for a sharp rise in population, many countries are set for a decrease in the population. But, the UK is a long way from a falling population. The ONS forecasts net migration will cause the population to rise to 76 million by 2050.

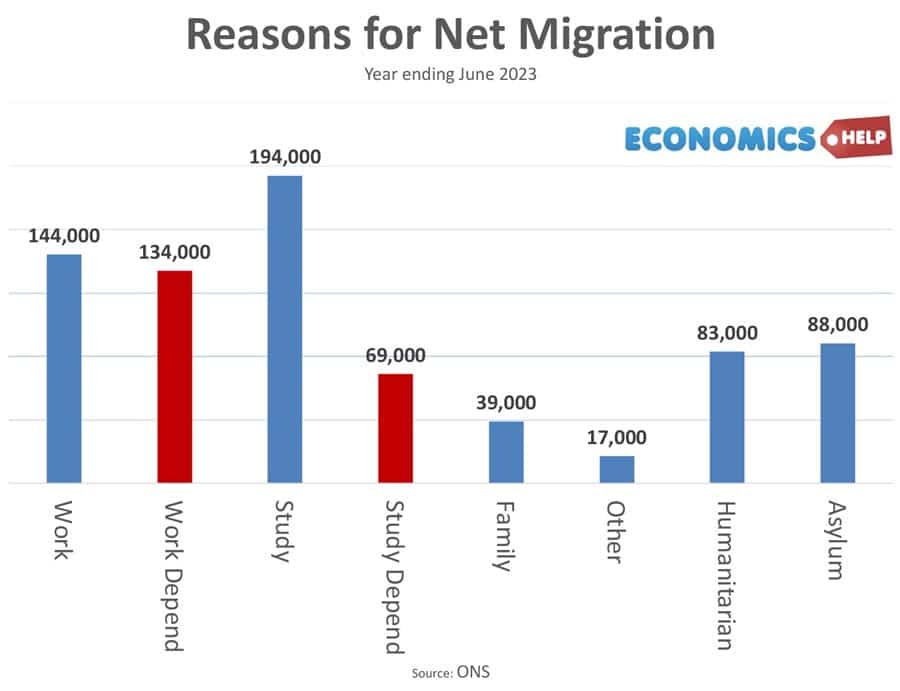

These are the reasons for net migration. I added small boat arrivals to place them in context of overall numbers. The main drivers of net migration are work and students. There are now nearly half a million students in the UK and they have become a very important source of income for British universities. Tuition fees from foreign students have grown from £1bn in 2003 to nearly £8bn in 2022, or 20% of total income. Given the annual losses of British universities, Foreign students are effectively keeping it going.

There is also an economic effect. The UK is essentially a service sector economy. Manufacturing has shrunk and higher education is one of the few industries where the UK has international advantages. Direct export earnings from higher education was £20bn in 2020. However, the rise in student numbers has placed more pressure on the broken UK housing market. How has immigration affected the broken UK housing market?

Housing

Housing is a legitimate concern of high migration. Especially in big university cities. The average student rent is now close to the average maintenance loan. Many young people are being priced out of the market. In 2018, the Ministry of Housing, used a model from the University of Reading, suggesting a 1% rise in households led to a 2% rise in house prices. Therefore, the 4.8 million increase in foreign-born households between 1991 and 2016, means immigration could be responsible for an estimated 21% increase in house prices over this period.

Now, If this model is true, in 2022, with a net migration figure of 600,000 being about 1% of the UK population, this suggests that net migration is responsible for house price inflation being 2% higher than otherwise. However, this model is an outlier in terms of pricing effects. The Migration Advisory Committee (2018) found that a 1% increase in the UK’s population due to migration increased house prices by 1%. This is similar to many other studies. But over the next few years, the high levels of migration will be a major factor in increasing the number of households. The problem is the population is rising faster than the supply of housing. And also the government target of 300,000 houses a year is not a magic number. A FT investigation suggests that in the light of recent immigration states the figure needed could be closer to 421,000 a year, yet this was a real challenge because UK has chronic difficulty in meeting government targets. If the UK was better at building housing, the impact of immigration would be different.

It’s important to say, that immigration is not the primary cause of the housing crisis. It is also a decade of low interest rates, rising wealth inequality and the sell-off of council houses to name but a few. But, on top of this fundamental problem, rising demand from growing number of households is exacerbating prices. It is one reason for the strong growth in rents in recent years. And It’s not just about rising prices, shortage of properties is changing household composition with more young people living with parents for longer.

Vacancies

The next question to ask is that if the UK is going into recession, how come we have so many job vacancies and need net migration to fill in jobs? This is a complicated one. It’s an unusual recession in that unemployment is relatively low. But, inactivity rates are quite high, in particular, rising long-term sickness. Also, some sectors of the labour market are not particularly attractive to native-born workers. For example, the UK has an acute shortage of NHS workers and care workers. Migration has become a key factor in keeping the NHS going.

With other 100,000+ vacancies in the NHS, immigration allows a wide pool of workers. Recent NHS data shows that across all NHS staff in England (1.4 million), more than 17 per cent (264,815) are from overseas. Without immigration, the NHS would facing even longer waiting lists. Already they are near record highs. In surveys, many say they would like lower overall immigration levels, but generally are supportive of immigration for key areas like NHS and care workers. But, this is the trade-off, how to reduce overall immigration without limiting key sectors. All sectors can make a convincing case they need workers.

Does net migration benefit the economy? A rise in population will increase real GDP. The economy will be larger, bigger workforce, and higher tax revenues. However, an increase in real GDP doesn’t mean living standards will necessarily improve. The crucial question is what effect does it have on real GDP per captia? For example, the UK has seen an increase in real GDP, but real GDP per capita is much less. Most of the increase in real GDP is due to population, but wages are not rising. The problem here is not migration, but the fact, the UK has lost ability to grow.

Net migration can have positive effects on economy, e.g. higher population density can be more efficient. Migrants tend to be young, more entrepreneurial and help economic innovation. Certainly in the US, there is long list of migrants who set up successful companies. Another big factor of immigration is that if they are young, skilled workers, they will tend to be net contributors to UK tax revenues. This is because they pay tax, but don’t receive pensions and so much health care. In 2019, a report found that EU migrants were net contributors to budget. Non-EU migrants at the time were not, because in that period, they were often elderly family members.

Public Services

A legitimate concern over immigration and rising local population is whether public services will be keep up with demand. In recent decades, austerity has hit many departments, we see shortages in health, housing, legal system and environment. Local councils are facing bankruptcy and there is long-period of under-investment. Therefore, the idea of rising population means that services will be increasingly stretched. The sad thing is that net migration should be creating more tax revenues to theoretically improve public services. But, government spending is so stretched, we only see the effects of austerity and waiting lists. But, if immigration was stopped, it would have a negative impact on the governments budget position and make it harder to cut taxes.

It is often claimed immigrants take native-born jobs, leaving domestic workers worse off. But, is this fair? This claim assumes the number of jobs is fixed. But, if you increase the population 10%, you will increase demand 10%, and so for every job an immigrant takes, another will be created. In a period of high migration, the UK has seen falling unemployment. In fact, it is the very low unemployment which is causing a rise in work related migration. If unemployment were to rise, it would lead to a fall in work related migration. This is an advantage of migration it makes labour markets more flexible.

Wages?

What about wages? Does low-skilled migration put downward pressure on wages. Evidence is mixed, but studies suggest little discernable effect. Until 2008, high migration was consistent with real wages growth. Since 2009, high migration has co-incided with low wage growth. But, the problem is not migration, but all the other factors pushing down wages in the UK.

The final point is that despite migration the UK has an ageing population, and this raises many problems such as falling tax revenue and higher demand for pensions and health care. For many countries, this decline in population is forecast to be severe and could lead to very severe economic problems. In the future, will we think that high levels of immigration could be a solution to the demographic crunch? This video on my global channel explains how much the world population could fall and what the consequences will be.

Sources:

“For example, the UK has seen an increase in real GDP, but real GDP per capita is much less. Most of the increase in real GDP is due to population, but wages are not rising”

If you add extra labour to fixed capital, then The Law of Diminishing Marginal Returns will mean that per capita GDP declines. That isn’t necessarily bad; it may still generate a surplus for pre-expansion workers and an increase in incomes for the new workers, if they came from low income countries.

Maybe our problem is shortage of capital. Fixing that may mean diverting productive resources away from consumption goods, meaning we will all be worse off, in the short run.

” Therefore, the idea of rising population means that services will be increasingly stretched. The sad thing is that net migration should be creating more tax revenues to theoretically improve public services. But, government spending is so stretched, we only see the effects of austerity and waiting lists. But, if immigration was stopped, it would have a negative impact on the governments budget position and make it harder to cut taxes.”

Tax revenues do not supply services; we need appropriately productive resources to do that. If net immigration does not increase such resources (or maybe reduces them in some areas) it will tend to stretch existing resources.

Money budgets work for individuals (who each consume very little) and to an extent to businesses. They never work at national level…at that level we must look at resources.