In May 2010, the Conservative coalition entered government against a backdrop of the great financial crisis, which had sent the pound tumbling, a deep recession and record government deficits. Cameron and Osborne blamed the crisis on high debt and wasted no time in imposing austerity measures on the economy. Yet, 14 years after the start of austerity, government debt has increased from 65 to 98% of GDP and the economy has faced the worst period of wage growth since the great depression. Low economic growth has caused a crisis in public services, with NHS waiting lists soaring, but is this economic malaise due to a combination of external shocks and bad luck or is it a self-imposed crisis due to poor policy?

In May 2010, the outgoing chief secretary to the Treasury left a note “”I’m afraid there is no money“” it was supposed to be a bit of dark humour, a private joke, but it was seized on by George Osborne who claimed the necessity of cutting spending. Osborne also cited the work of Reinhart and Rogoff who claimed that high debt led to lower economic growth. It was influential paper which popularised austerity on both sides of the Atlantic.

Austerity

The first problem with austerity, is that the link between debt and growth was a mirage. The Rogoff paper was later discredited. In the aftermath of the great recession, private investment was very weak. Government austerity on top of this, pushed the economy into a prolonged stagnation, from which it has struggled to emerge.

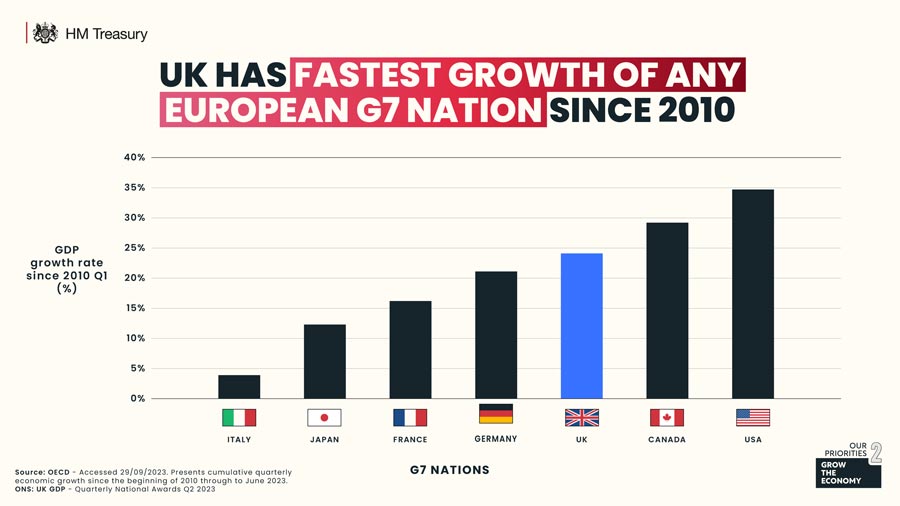

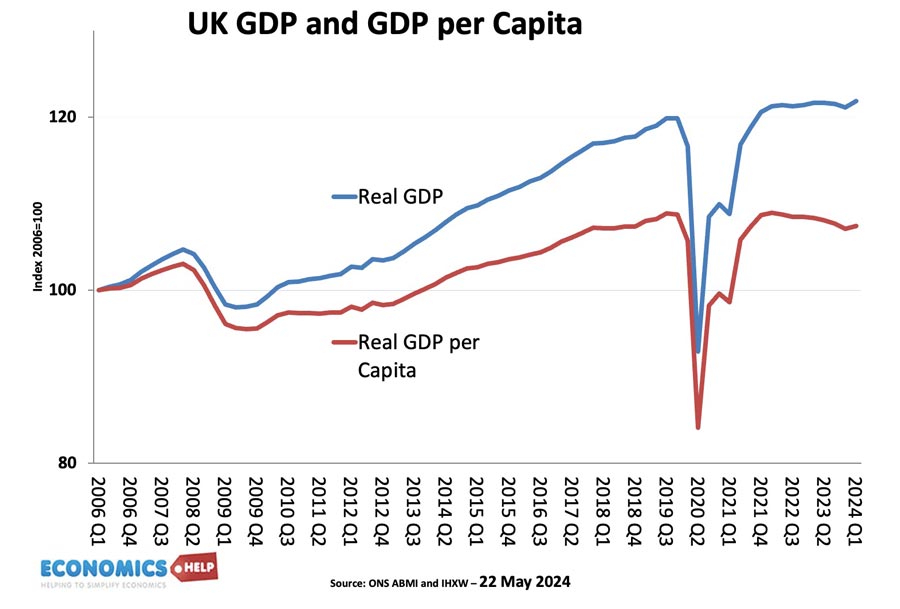

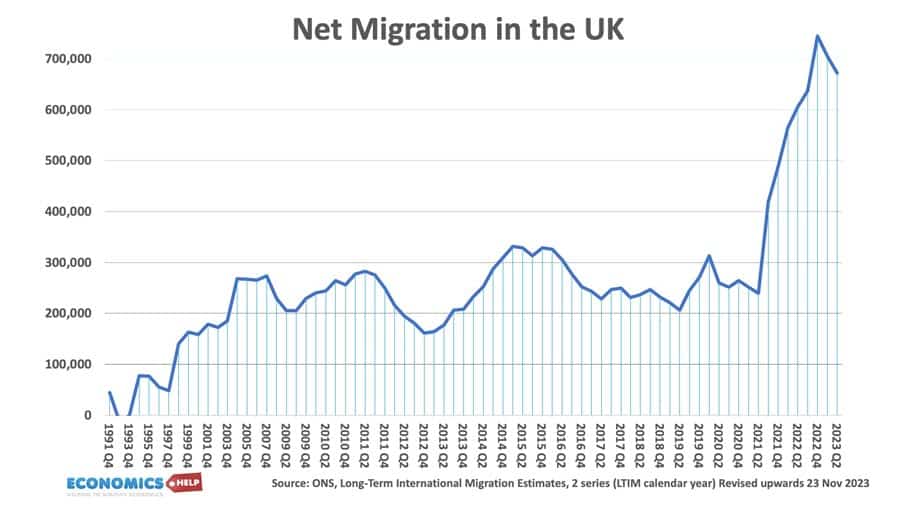

At this point, the government could claim that compared to Europe, UK growth was not that bad, in fact it has been higher than some EU countries. But, firstly, the Euro debt crisis of 2012 led to the EU’s own self-inflicted austerity pain. The more countries pursued austerity, the bigger the economic cost. Italy and Greece both suffered falls in living standards. In the 2010s, the UK didn’t have the straightjacket of the Euro the UK had the freedom to pursue its own economic policies. In fact the government was helped by the Bank of England literally creating money and buying bonds. But, another aspect of UK economic growth in the past 14 years has been the reliance on a growing population. Net migration pushed up the population and headline GDP statistics, but, if we adjust for population growth, the UK economic performance is less impressive. It explains why real wage growth in the UK is one of the lowest in Europe.

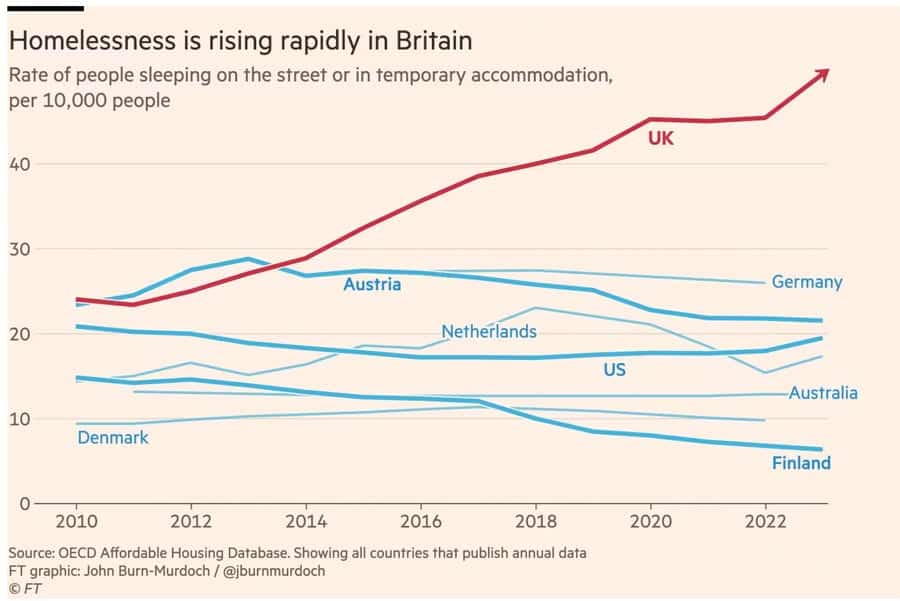

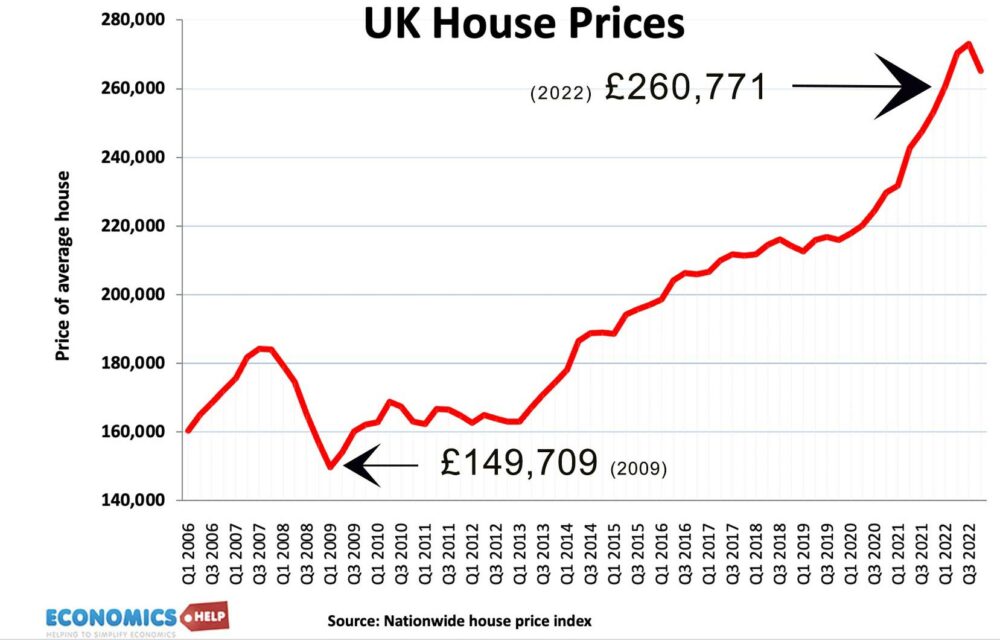

Some might claim there was no alternative to austerity – without spending cuts, bond yields would have soared and markets lost confidence. But, this is dubious, in the 2010s, with low inflation and low interest rates, it was cheap to borrow, even as debt rose, bond yields fell. The private sector were reluctant to invest in a stagnating economy. But, what austerity did is store up long term problems, which are ironically proving quite costly to the society and government. One of the hardest hit sectors was justice and prisons. It has led to overcrowding, prisoners released early and and backlog of court cases. Another target of austerity was local councils, Housing investment was cut significantly, which had led to a growing shortage of new builds. Yet, ironically housing wealth was one of the few areas to see rapid growth in the past 14 years. Low interest rates and shortage of supply caused prices and rents to soar, leading to those without housing wealth, faced with higher housing costs and leaving the UK with one of the highest cost of housing in the world. Rather than tackle underlying issue a short-term sticking plaster solution was the government’s help to buy. Helping young borrow more, but only pushing up prices more.

Housing Crisis

Cuts in the housing budget is an example of self-defeating austerity, with the housing crisis has imposing huge costs on the economy such as rising Housing benefit, record rates of homelessness, and lower disposable income. It is important to stress, the housing crisis has many components and the failure to build housing goes back to the 1980s. But, the 2010s was still a missed opportunity with even modest government targets frequently missed.

Brexit

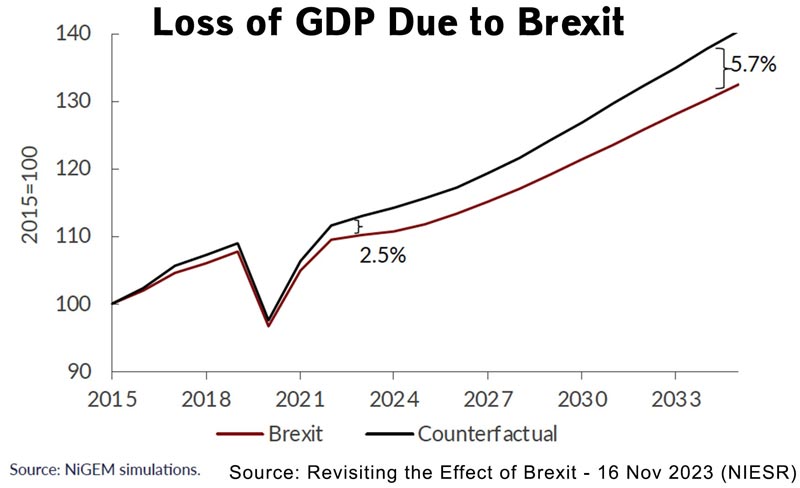

By 2016, the worst of austerity was over, but the next big impact on the economy was the Brexit referendum and the later decision to go for a hard Brexit of leaving single market and customs union. Whilst there were many external shocks outside the government’s control, Brexit was entirely driven by government policy. The process created uncertainty and led to sharp fall in investment growth, leaving the UK with the lowest rates in the world. The new trading arrangements have seen rising costs, trade barriers and new regulations. Unsurprisingly exports of goods to Europe have fallen.

Even this year, importing firms face new barriers for importing perishable food. Various studies estimate the impact of Brexit to be a net loss of 4-5% of GDP. NIESR estimate the cumulative cost of Brexit will be in the region of £2,300 per capita by 2035. Brexit didn’t cause a sharp drop in GDP, there was certainly no Brexit recession, more like a slow puncture, reducing growth by a barely noticable 0.2% a year. But over 20 years, it adds up to considerable loss of potential income and loss of tax revenues. There were alternatives to the hard Brexit chosen, in the referendum, many leavers gave the impression we could stay in the Single market, the customs union was barely mentioned. But, government choices were a key factor in pushing country to a hard Brexit, an outcome that seemed inconceivable in 2016.

One of the driving forces of Brexit was high migration from eastern Europe. Ironically, post-Brexit migration surged from non-EU countries to a record 700,000 a year. This was driven by work visas, student visas and also a higher percentage of family members. Despite high migration, a significant constraint to growth has been the lack of skilled staff with firms reporting real difficulties recruiting staff. In recent years, there has been a surge in long-term sickness and people leaving the labour market. It has particularly affected the UK. Whilst there are many factors behind this worrying trend, and many beyond the scope of government policy, but record NHS waiting lists and a healthcare system under great stress has not helped.

Covid

If Brexit was entirely self-inflicted, Covid was entirely beyond anyone’s control. It caused the government to adopt much greater levels of state intervention with a furlough scheme that supported workers during lockdown. The government spent between £310 and £410 billion on state support, causing national debt to rise. Whilst policies like Eat Out to Help Out were highly dubious given later lockdowns, the government intervention was important in avoiding the worst of the crisis.

Ukraine War and Inflation

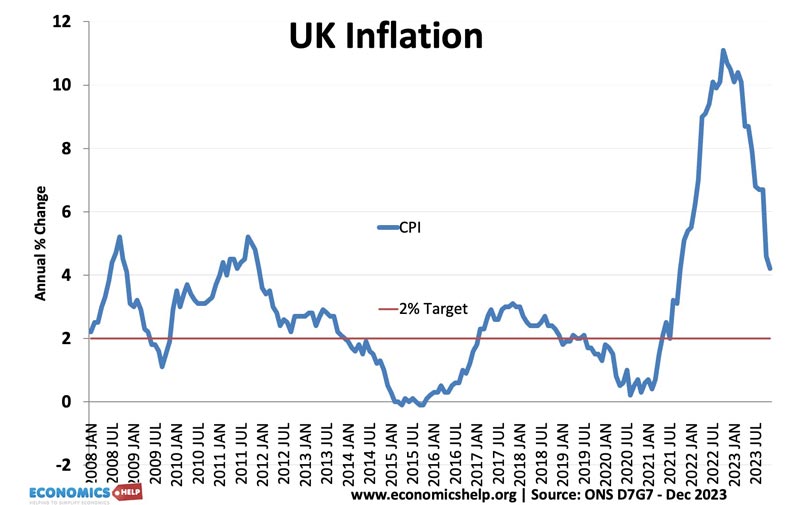

Hot on the heels of the Covid pandemic, the Ukraine War caused another painful economic shock. After being low for over two decades, Inflation soared to 11%, causing a cost of living crisis that led to falling real incomes and real financial distress. The inflation was focused on food and energy, which tended to affect low income households more. The impact would have been even greater, without the government’s energy price cap guarantee, which cost an estimated £37bn. The government are correct to point out that inflation was a global phenomenon largely beyond their control, though it is telling that the UK were particularly sensitive seeing a much larger increase in prices than other countries.

Truss Kwarteng Budget

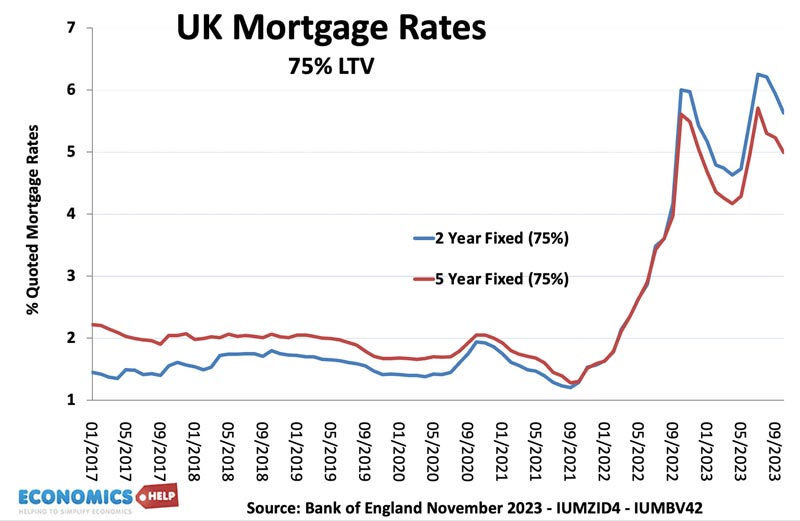

Despite a generous energy price guarantee system, it was lost on the electorate amidst the chaos of the Truss/Kwarteng mini-budget of 2022. Correctly diagnosing the UK’s low economic growth of the past 12 years, they introduced a budget worth £190 billion of unfunded tax cuts, primarily for companies and high earners. But, markets were spooked by the size of the tax giveaways at a time of high inflation and rising debt. The Pound fell, and bond yields soared. International commentators referred to the UK bond’s idiot premium due to the reckless budget.

Despite the market panic, a few days after the disastrous budget Kwarteng doubled down, saying they would just cut taxes more. It was a tone-deaf response. Homeowners acted in horror as mortgage rates soared. Pension funds were at risk of meltdown and needed bailing out by the Bank of England. Not only was it a disaster for markets, but in the middle of a cost of living crisis, it offered huge tax breaks favouring the highest earners. In Covid, the motto had been we’re all this together, the budget blew that away.

But, fundamentally, it was budget praised by free-market think tanks, which ironically was destroyed by the markets themselves.

The removal of Truss and reversal of the budget, saw some stability return, though mortgage rates remained elevated, primarily because inflation was proving more stubborn than the Bank of England hoped.

The government went from one of the biggest tax giveaways to one of largest tax rises in history. And this has been a feature of the past 14 years, frequent flip flopping on policy and tax rates. The UK tax share rose to the highest post-war level. yet, despite rising taxes, many public services and local councils remained squeezed for funds. Recent tax cuts are premised on future unspecified cuts to spending, which again will fall on the hardest hit sectors like education, justice and local councils. The IMF warn of a £30bn black hole in UK finances, and that is before, all the growing pressures of an ageing population, falling tax revenues from petrol cars and tobacco.

What about successful economic policies?

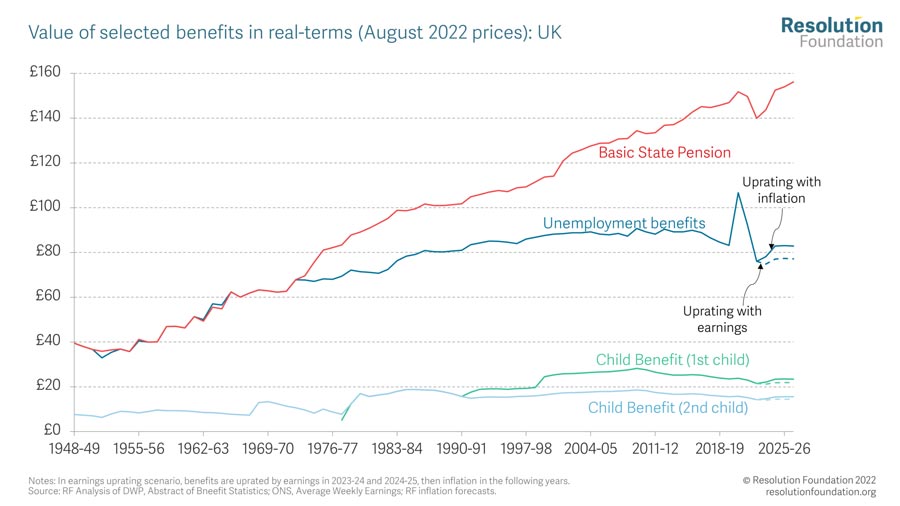

George Osborne surprised in 2015 with a significant uplift to the national minimum wage. The new National Living wage has done much to increase pay for the lowest paid such as bar staff and cleaners. These low paid workers have seen above average wage growth. Yet, despite higher wages, there is no adverse impact on employment. The biggest losers have been public sector workers who have often borne the brunt of austerity with nurses seeing real wage cuts in the past 14 years. The very recent shift from NI to income tax could help redress the balance from workers to better-off pensions and encourage labour market participation, though very recently government have promised to do a u-turn and give pensioners a quadruple lock.

Who has lost the most from the past 14 years? Whilst pensions have been triple locked, most benefits for working-age people have been squeezed, often falling behind living costs. With rising housing costs, households out of work, with more than two children, have seen particularly big losses, unsurprisingly child poverty has started to increase after many years of improvement.

The past few decades have also seen a bigger divide on housing with a contrast between those who benefited from rising house prices and those struggling to save a deposit or pay private rents. The loss of social housing began decades earlier, but no effort to reverse it was really made.

Overall, it’s been a difficult 14 years. There have been four major economic shocks. The great financial crisis, global productivity slowdown, Covid and then oil price shock due to the Ukraine War. Yet, at the same time, the government have made major blunders. Austerity when the economy was weak, reckless taxcuts when there was inflation, and the unforced option of Brexit. Outside these areas, the major problems of the economy have seen rather piecemeal attention, a housing crisis, deteriorating public services and low productivity have seen little more than sticking plaster policies and a focus on side issues.

Related

External Links

The Conservative government’s economic record from 2010-2014 is marked by the implementation of austerity measures aimed at reducing high debt. However, these measures led to prolonged economic stagnation, increased government debt, and a crisis in public services, questioning whether the economic difficulties were due to poor policy choices or external factors.