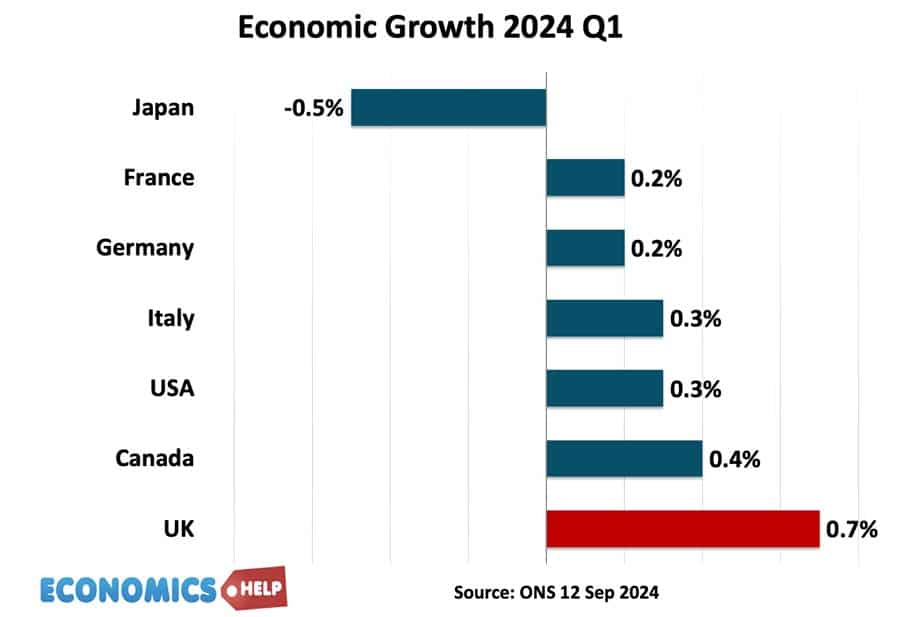

Last May, Rishi Sunak could boast that the UK was the fastest growing economy in the G7. And, after a fashion, he was correct. Not only that but UK inflation has fallen close to its target of 2% and Sterling has reached its highest level for eight years. Were the Tories about to do the same as 1997 and gift Labour an economy ready for a prolonged economic boom? But if that is all true, how come, Labour are trying to claim they have inherited the worst ever economy and are seem insistent on painting a picture of misery and despair?

Firstly, if we take economic growth, the claim of fast growth is deeply misleading. We did slightly better than depressed economies for one quarter.

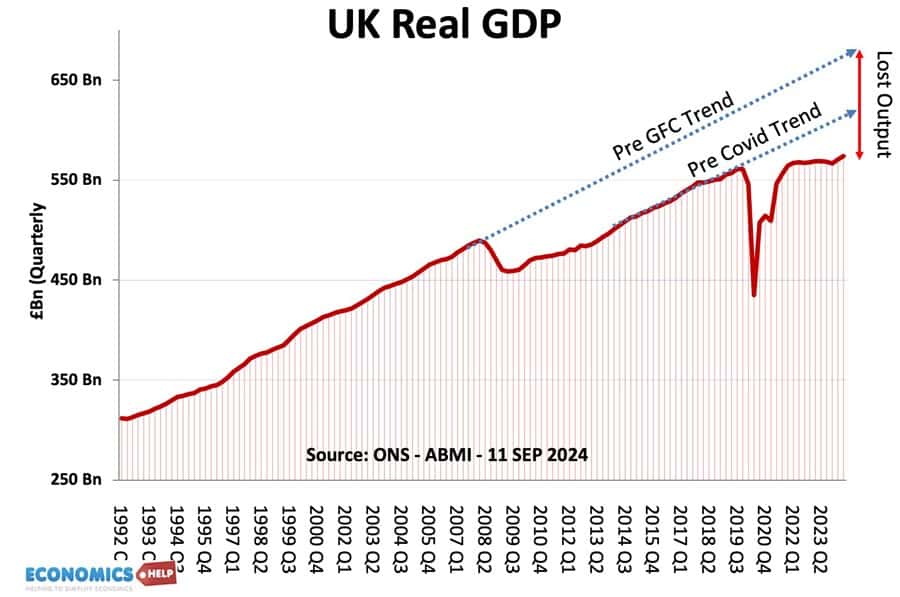

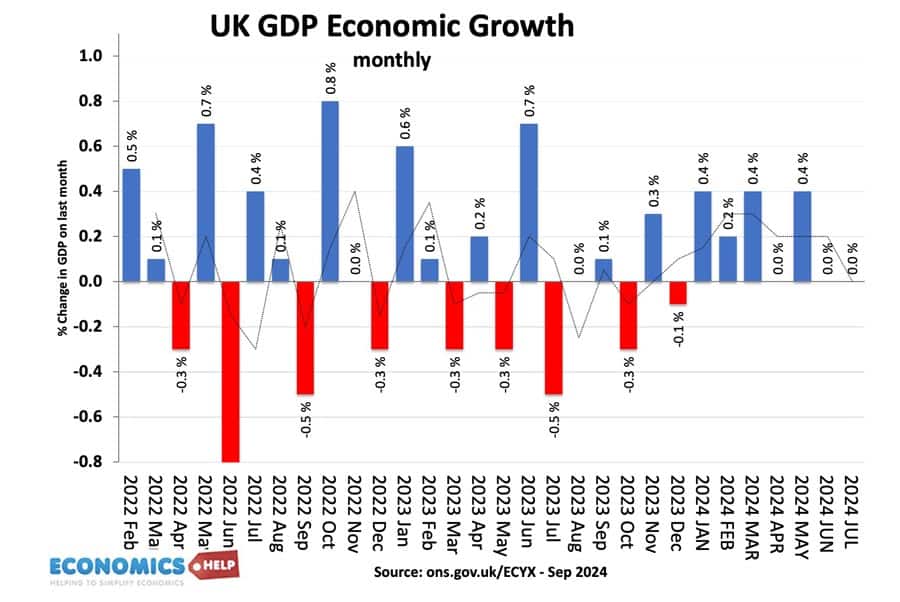

But if we look at a wider context real GDP in the UK is barely increasing. UK Growth was fast in the first quarter partly because it bounced back from the recession of last year. And since that good start to the year, growth has gone into reverse. The past two months have seen zero growth, worse than market expectations, and will be a cautionary lesson for those hoping for a more optimistic UK future.

It highlights the danger of focusing on one economic statistic. And also this is why ordinary people can feel a disconnect between their ordinary lives and economic statistics. Despite fluctuations in GDP, the basic story is that of a stagnating economy. In the UK it is important to look at real GDP per capita because a growing population has made real GDP growth look better than it really is. If we adjust for population, real GDP per capita is still lower than 2019. And it is this that really stands out. It is the worst period for real wages in living memory. We have got used to rising living standards and when they fall or stagnate, it can feel like a recession, even if technically it isn’t.

Reasons to be more optimistic

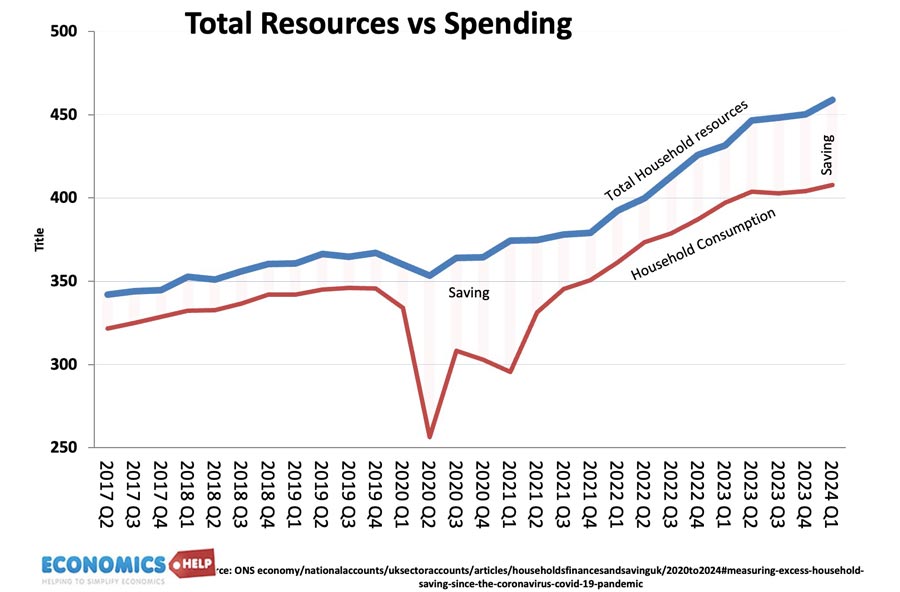

However, from another perspective, the macro economy does have some positive glimmers on the horizon. It is a relief that inflation has fallen, particularly welcome is the decline in services inflation. This raises the prospect of lower interest rates in the coming months. It may only be half a point cut, but it will help business and mortgage holders. Don’t forget 18 months ago, there were fears of interest rates rising to 6%, and this led to a big drop off in confidence and rise in cautionary savings. In fact, this unusually high savings rate is a reason some are hopeful, that growth will pick up in the future. Usually, the UK economy is pushed along by high spending, high borrowing and spending everything we have. This makes the economy vulnerable to a boom and bust like early 90s and 2008.

But, the past couple of turbulent years have led to a rise in savings. It means, in theory, households have more room to increase spending without taking on debt. If the overall climate is more stable, then workers have the means to increase spending and firms may finally start to invest more. Also, the fall in inflation has led to a small rise in real wages – a welcome turn-around from recent years.

Uncertainty

One thing people and business hate is uncertainty and that has been a feature of recent years. At the moment, there is still considerable uncertainty about Labour’s first budget with banks and high income earners, nervous about prospective tax rises. This could explain some of the current weakness in growth. Another reason for long-term optimism is that in theory, the UK should have lots of spare capacity. The post-war trend rate of growth was 2% but with actual growth falling behind, there should be the prospect of catching up lost ground. There are new technological improvements coming in the realm of battery technology, improved solar energy, AI and automated processes. However, hoping for growth to catch up lost potential is in danger of becoming a cliché. The story of the past 15 years is of optimistic forecasts being proved wrong and a continued slump in productivity growth. The really big question is will a Labour government be able to do anything different to the past 14 years?

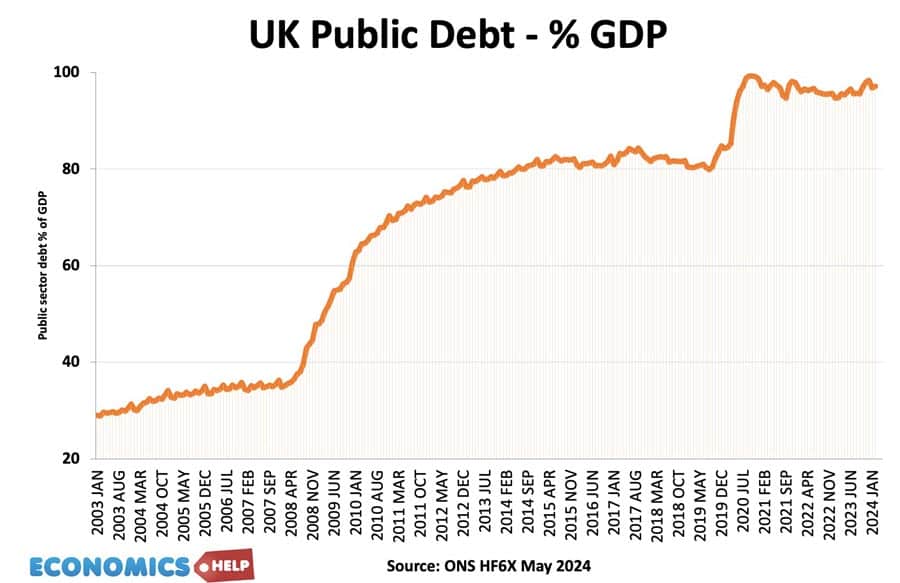

But, first why do Labour say there inheritance is the worst in post-war period when in terms of inflation, growth and unemployment it definitely isn’t. What they mean is the state of public finances. On this grounds, there is merit to say the situation is pretty dire. Under the conservatives austerity decade, taxes as a share of GDP actually rose, despite many public services being cut to the bone. Yet, at the same time debt rose to nearly 100% of GDP, giving governments who worry about deficits less room for manoeuvre. This is especially reflected in unprotected areas like prisons, justice system and housing.

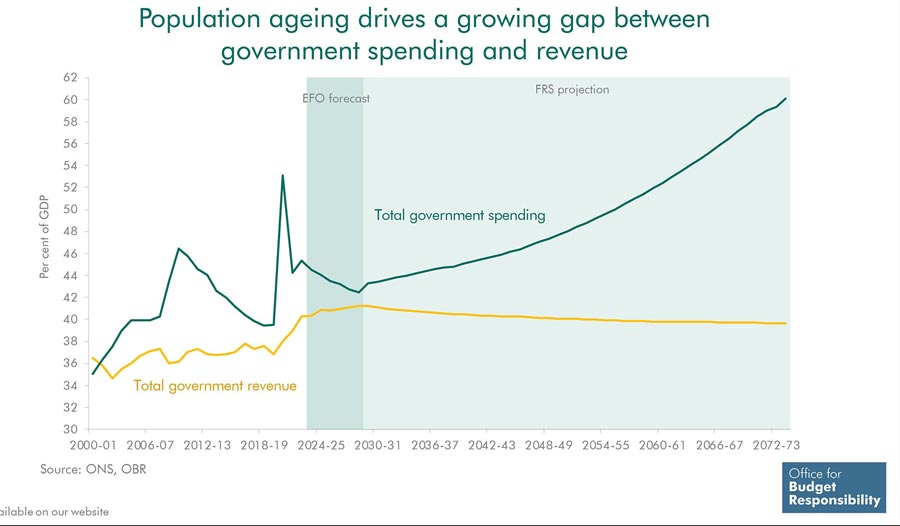

The ONS forecast a dire situation for government spending on current policies.

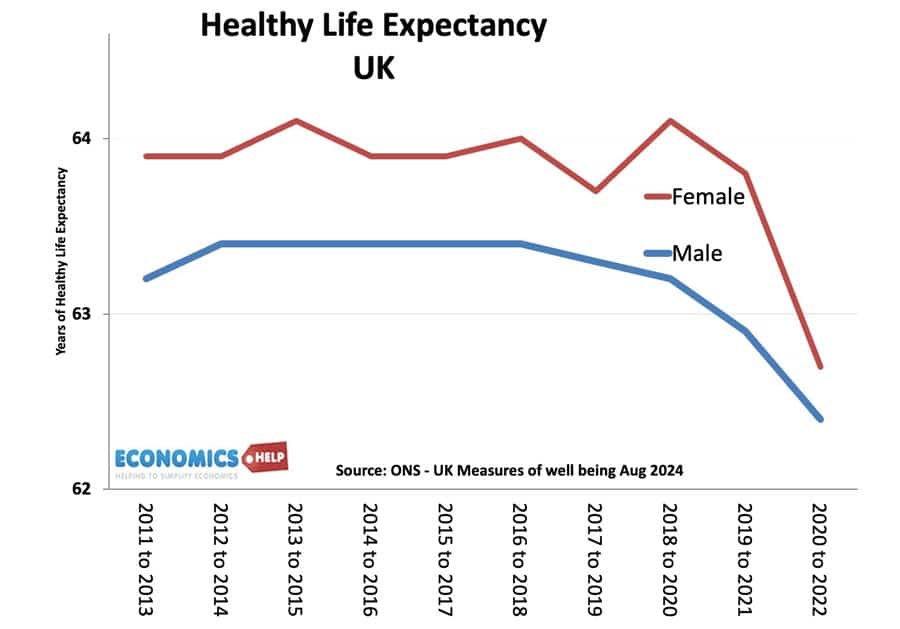

There is a real crisis, which is why prisoners have to be released early, and why there is such a backlog of court cases. The problem is that the UK population is ageing, and demand for health care is rising much faster than the economy is growing.

It’s not just an ageing population, but decline in health life expectancy and increased cost of modern medicine. Across the world, you see tax shares rising as a share of GDP. By international comparison, the UK tax burden is not particularly high. But, with the government ruling out any major tax rises, they are left scrambling around for ways to save money. In the post-war period, we could afford to increase health spending by reducing defence spending. But, that free meal has come to an end, if anything defence spending needs to rise. So any government faces an impossible juggling act of trying to keep up with demand for public spending. There has been a fierce political backlash to removing winter fuel discounts, but at £1.6bn a year, this was a drop in the ocean to the expected rise in pension spending in the coming years.

NHS Waiting Lists

NHS waiting lists have risen to 7 million, with some suggesting the real figure could be even higher. It will prove very difficult to improve. The government has resorted to cutting public sector investment to meet fiscal rules. This is the easiest short-term fix, but it stores up problems for the long term. Poor infrastructure and energy dependency all cost the economy. This has resulted in congestion, potholes on the roads and lack of affordable housing. This is the real economy for ordinary people, and why GDP statistics can seem irrelevant if you can’t get a doctor’s appointment or afford rent.

The new government are caught between wanting to increase investment and wanting to meet fiscal rules. On the one hand, they are trying to boost housing supply, on the other hand, they have scaled back some infrastructure projects. At the end of the day, the government’s public investment plans are very modest. It seems so far, the government is leaning more towards Treasury orthodoxy of balancing the books – we can’t afford it seems to be the mantra. And so there is a danger of the UK repeating the same cycle of austerity and low growth we saw 14 years ago. The government would be better advised to worry more about increasing investment than meeting fiscal rules which are of debatable value.

Global Factors

However, it is important to bear in mind, even government’s are not all powerful, the economy is influenced by forces beyond its control. On the postive side oil prices have fallen helping reduce inflation, but this more reflects the risk of global recession, which would be damaging for the UK economy, where exports are still an important part of economy.

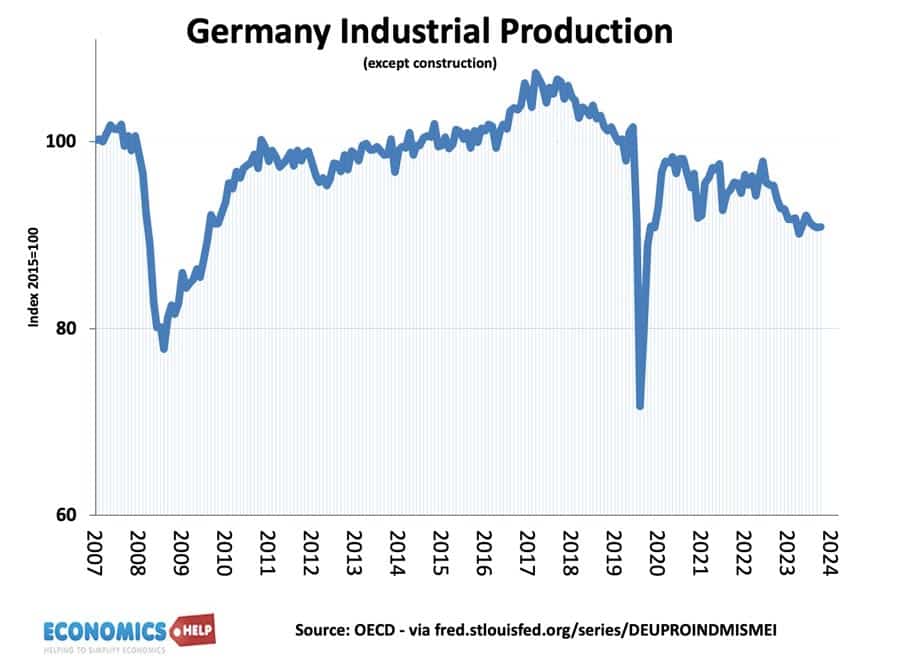

The whole of western Europe is struggling to grow. Even the US, which has achieved impressive economic performance in recent years, is starting to stutter with some recession warning signals starting to flash. This is a great concern for the UK. The recent report by Mario Draghi laid bare the lack of dynamism, flexibility and willingness to invest in Western Europe. The German economy is stuttering along, and it is no comfort to say we are growing marginally less badly than Germany because ultimately if the German economy struggles it will negatively affect all of Europe. Despite Brexit, the UK is still influenced by what happens in Europe.