In 1913, Britain was the largest trading nation in the world. 50% of global capital investment came from London. It was an economic powerhouse which defied its small size.

But, in the past 100 years, the pound has devalued and the UK has seen a steady decline in relative importance. Some of this was inevitable, but in recent decades, self-inflicted blunders have led to an economic stagnation, with the UK experiencing some of the lowest wage growth in the world.

In 1913, the UK was still riding high on its roles as the first country to industrialise, the first country to develop railways and its Empire which still covered 25% of the world’s land surface.

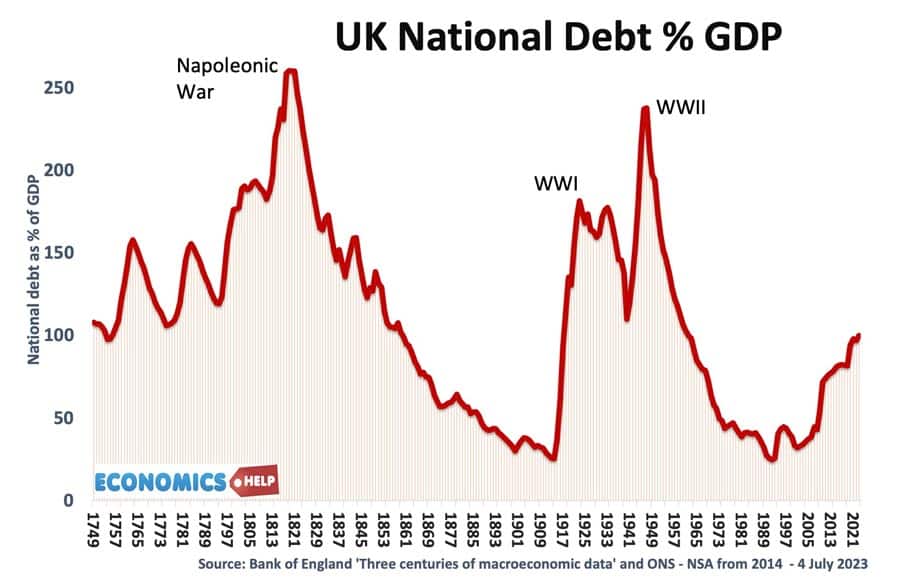

The First World War was a major shock, hitting global trade, and causing a surge in national debt. But, even after the War, the economy struggled. Firstly, UK firms lacked dynamism and productivity. The UK elite focused on learning Latin in public schools and saw manufacturing as less desirable. Lacking skilled workers and entrepreneurial spirit UK firms lost ground, especially to American firms.

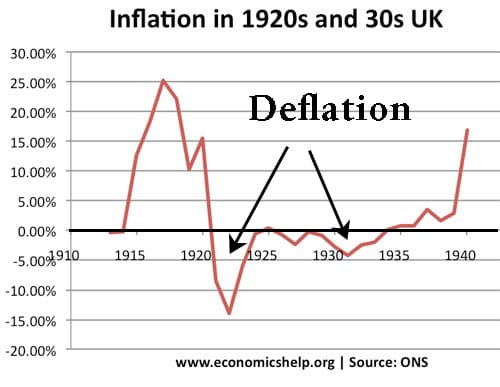

1920s Deflation

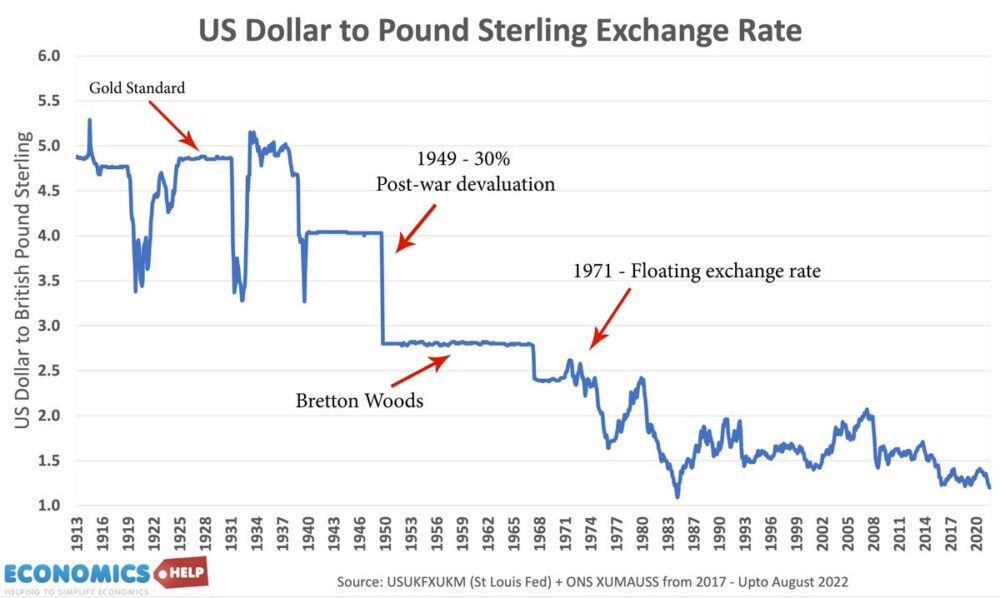

Despite economic decline, in 1925, Winston Churchill, the then chancellor took the UK back into the gold standard at the pre-war level of £1=$4.86. It was hoped this would bring back the glory days of the pre-war era. But, the Pound was vastly overvalued, it led to deflation, low economic growth and high unemployment. It was vociferously opposed by John Maynard Keynes but to no avail. The UK entered a depression even before the Wall Street Crash of 1929. The 1930s was no better. The response of Treasury economists to the great depression was to cut unemployment benefits in a bid to balance the books. The path of austerity was opposed by John Maynard Keynes, who would go onto to create a new branch of economics to challenge the classical orthodoxy. The only relief came from leaving the Gold Standard in 1931 and the development of Metroland around London.

Post-war period

The Second World War was another shock to the UK, virtually bankrupting the country, It lost nearly a 1/5 of its wealth. At the end of the war, the UK had to negotiate a loan from the United States. But, rather than using the Marshall Plan funds to invest in industrial modernisation, the budget was largely used to keep up the pretence of being a major global player. On the continent, France, Germany and Italy invested in the modernisation of industry and quickly caught up with the UK. By the 1960s, Britain’s railways still ran on steam and mechanical semaphore signals. It might have been the first country to build railways but it was also the last to leave the steam era behind. The Beatles wowed the world, but behind the scene the economy was hampered by a class system, lack of vocational training and poor infrastructure. British Leyland cars were a watchword for poor quality. It was unsurprising the UK grew at a slower than the continent.

Also, the UK was adjusting to an age without an Empire. Previously the UK had benefited from a captive market and monopoly access to raw materials. But, the new US-led Bretton Woods system, led to a decline in trade with the Commonwealth and growth in trade to Europe. Although the UK turned down the first opportunity to join the European Economic Community in 1957, this was later viewed as a mistake and sought to gain membership. But, after being twice vetoed by French president Charles De Gaulle, it was not until 1973, that the UK joined the EEC.

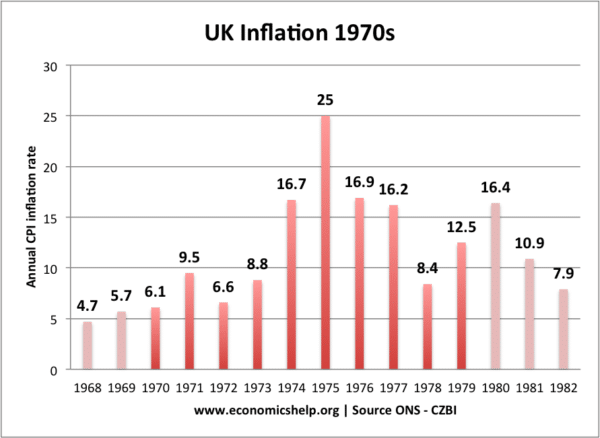

1970s

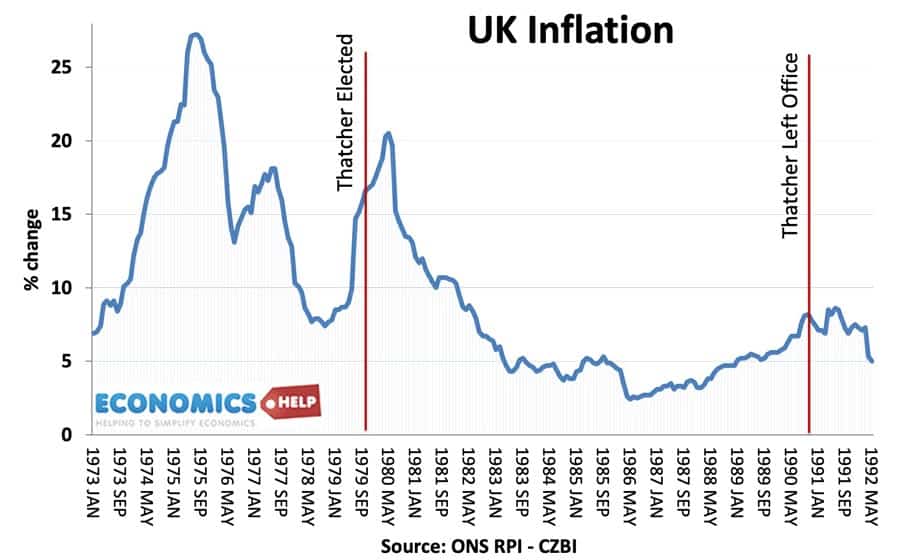

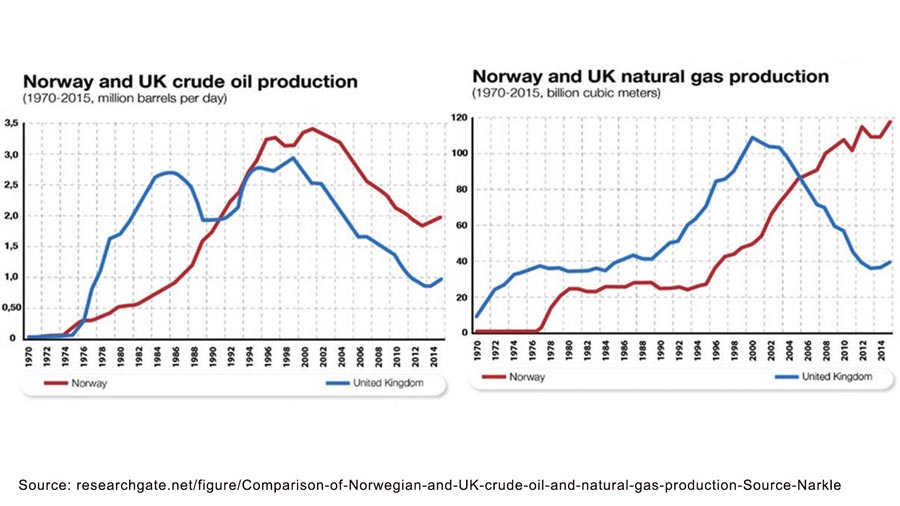

The 1970s was another turbulent decade, with oil prices causing a surge in inflation. This led to industrial strife with unions frequently striking for higher pay. By the end of the decade, the UK had the ignominy of being the first developed country to approach the IMF for a bailout due to balance of payments crisis. Yet, one ray on the horizon was the discovery of North Sea Oil which looked to be a potential saviour.

Thatcher’s Revolution

Against the backdrop of high inflation, the winter of discontent and economic gloom, Mrs Thatcher won a pivotal election in 1979.

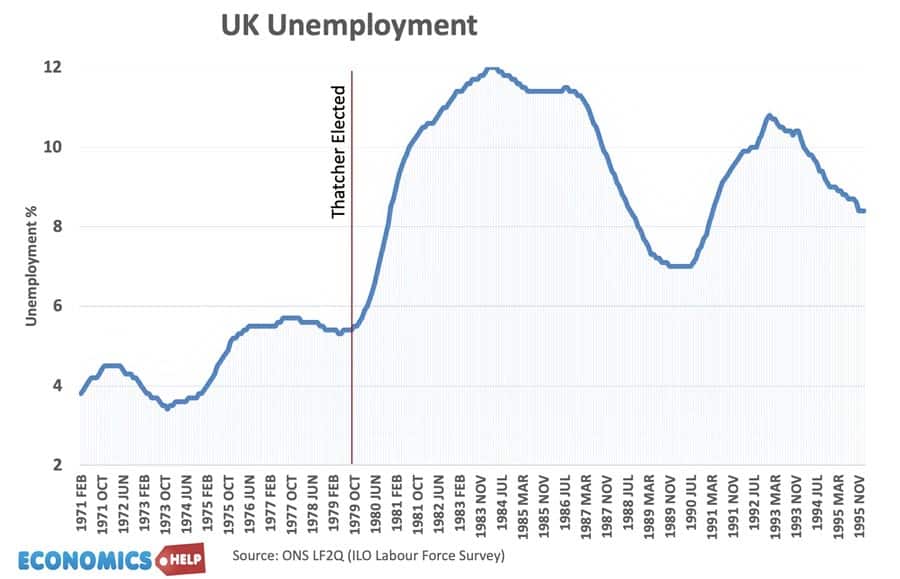

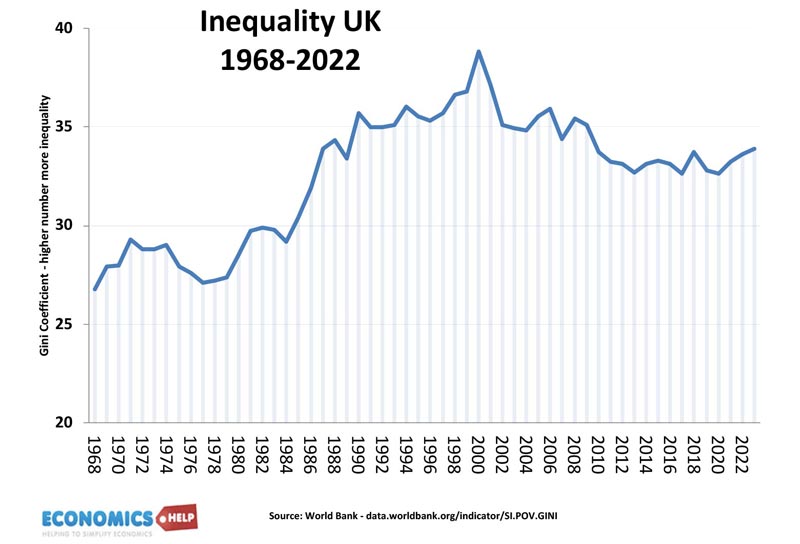

Initially, her economic medicine of monetarism caused a deep recession and decline in the industrial base of the UK. Unemployment soared and manufacturing never really recovered. The 1980s saw a widening of inequality and a shift to a service sector based economy, increasingly focused on London.

In fact the 1980s, seemed to give a two speed economy – a booming and prosperous south east and the left behind regions in the north. This is a legacy which remains today, take out London, and average GDP per capita is lower than every region in the US and Netherlands.

Oil

Even the big boon of North Sea Oil was a mixed blessing. It contributed to a temporary surge in Sterling which worsened exports and hit manufacturing. Revenues rather than being invested were used to fund income tax cuts. Thatcher significantly reduced tax rates, especially for high earners. The UK produced a similar amount of gas and oil to Norway, its neighbour across the sea. And although Norway has a smaller population, they were able to invest in a sovereign wealth fund, which now stands at $1.3 trillion – the largest in the world.

The UK has nothing – a reflection of the ideology of privatisation. The 1980s saw major industries sold off to the private sector. Even council houses were sold off, something which would hurt the housing market later. Thatcher was also a big supporter of the EU Single Market, the idea the UK would benefit from removing all barriers to trade with Europe. Another significant factor was the big bang financial deregulation of the late 1980s. City financers were pretty much free to act unregulated, and this saw another boom for London as a major trading centre.

Lawson Boom

The radical economic policies of Thatcher and Lawson saw economic growth reach 4% by the late 1980s. House prices rose 35% in a single year. There was talk of an economic miracle, the sick man of Europe, now leading the way. But, behind the impressive statistics was the familiar problem of growing inflation. It was no miracle, just an economic bubble. Higher interest rates brought the party crashing down and the economy slipped into recession. A recession made worse by membership of the Exchange Rate Mechanism, which had kept the Pound overvalued a mistake reminiscent of the gold standard in the 1920s. On Black Wednesday, the UK left the ERM, the Pound devalued and away from the bad headlines, the economy went on to experience the longest period of economic expansion on record. But, it did leave the UK very dubious about joining the Euro.

Credit Crunch

New Labour inherited a strong economy, inflation and debt was low, growth was positive. And with a stable economy they could increase spending on public services, such as health care. It seemed the UK had finally cracked it, an end to boom and bust. But, alas, the appearance of stability was misleading because the unregulated financial markets had gotten out of hand. Complex financial derivatives were contributing to one of the biggest asset bubbles in history. When the bubble burst in 2008, the UK was uniquely hard hit. Relying so much on financial services meant tax revenues and GDP fell very hard. The Pound devalued nearly 30% and the budget deficit soared, inconveniently just before an election.

Austerity

Cameron and Osborne capitalised on the crisis to promise an end to debt and a new era of austerity. Even whilst the economy struggled to recover, spending cuts pushed the economy back into stagnation. Not only did growth suffer, but so did long-term fabric of the economy. Public services, public investment were all cut to the bone, leading to a chronic rise in waiting lists and dissatisfaction. Even the government’s flagship investment project HS2 was eventually pushed into the sidings, the country of Brunel, could no longer build. The tragedy is that there was no actually need for austerity. In 2010, public sector debt was low by historical standards and interest rates were near zero, making borrowing cheaper. It was a return to the Treasury orthodoxy of the 1920s and 30s. Keynes was turning in his grave. Growth was so low, that austerity even failed to prevent debt from rising. It marked an end to the post-war economic boom. Even in the so-called crisis of the 1970s, real wages had grown, but not anymore. The trend rate of growth was broken and dissatisfaction rose.

Immigration

The UK had long been a country of migration. 2.6 million came from the Commonwealth in the 50s and 60s. The 2000s, saw a new source of migration from eastern Europe. Net migration figures increased to the highest level on record. At a time of austerity and stagnant wages, immigration became a lightning rod and in 2016, the UK voted to leave the EU. It was a shock that saw the pound devalue by 13%. But, at the time no-one quite foresaw how it would lead to a hard Brexit, exiting the customs union, single market and the reappearance of custom barriers, checks and regulations. It was like going back 100 years. Models suggest Brexit has cost the UK economy around 4-5% of GDP by 2030. A loss of living standards, the UK could ill-afford given the ongoing economic stagnation. An economic stagnation worsened by a housing crisis and lack of affordable homes.

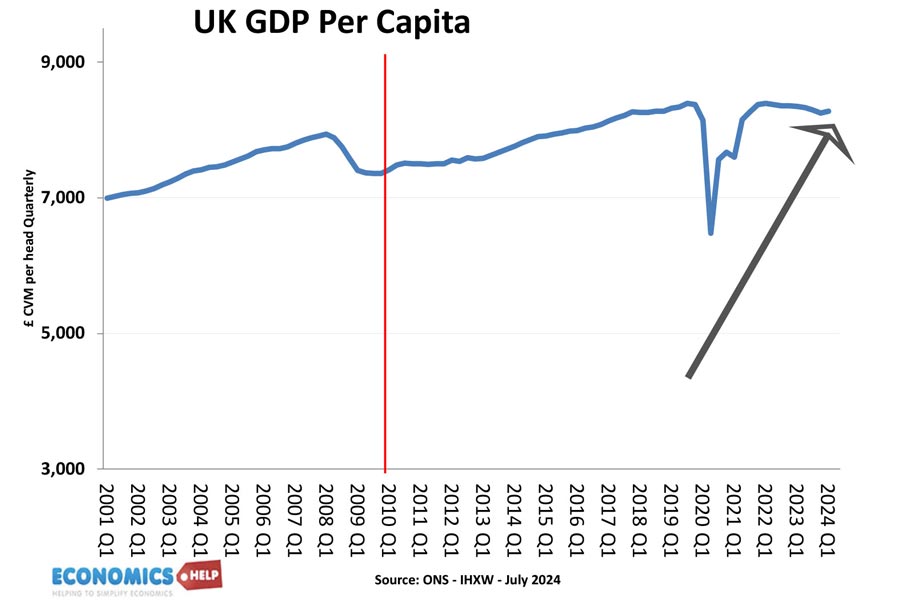

Since 2008, the UK has struggled to grow. GDP figures have been massaged by high levels of immigration, but if we adjust for population, GDP per capita has become stuck. A reflection of low investment and low productivity.

Related

In 1950, British output per head was still 30 per cent over that of the average of the six founder members of the EEC, but within 20 years it had been overtaken by the majority of western European economies.[5][6]

By 1913 about 50% of capital investment throughout the world had been raised in London, making Britain the largest exporter of capital by a wide margin

Britain remained the world’s largest trading nation by a significant margin: in 1914

9.5% in 1830, to 22.9% in the 1870s. It fell to 13.6% by 1913, 10.7% by 1938, and 4.9% by 1973

Levels of trade with the Commonwealth halved in the period 1945–1965 to around 25% while trade with the EEC had doubled