The Australian economy is unique. 35% of the country is practically desert and geographically it is isolated. 98% of its trade is exported by sea.

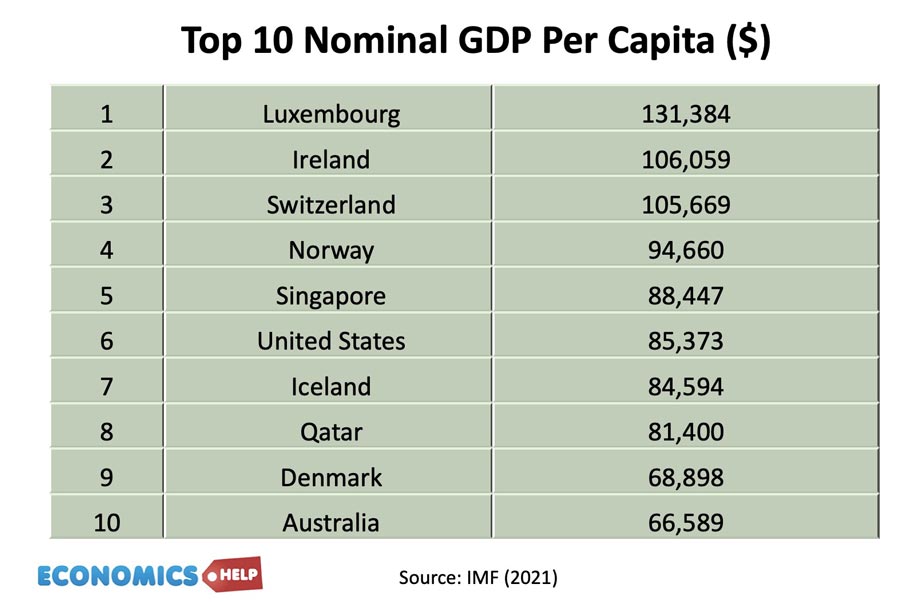

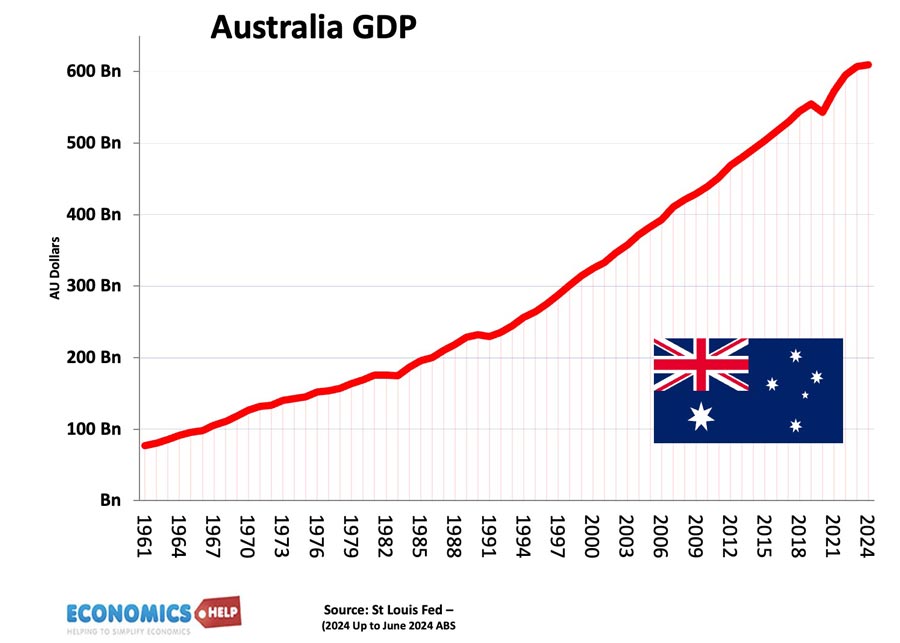

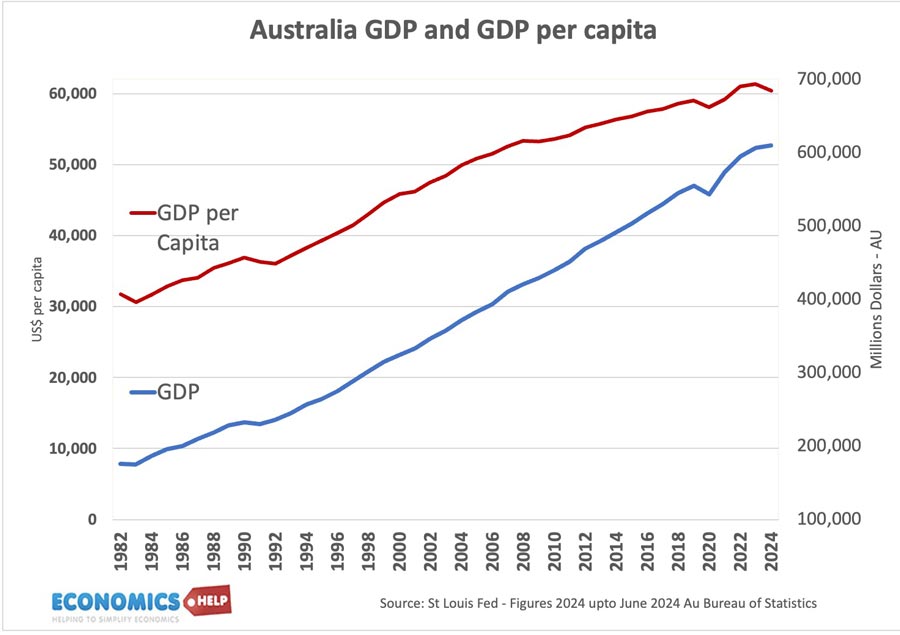

Yet, it has become one of the richest countries in the world. Richer than the UK, France and Germany. From 1991 to 2020, it experienced the world record for the longest continued period of economic growth.

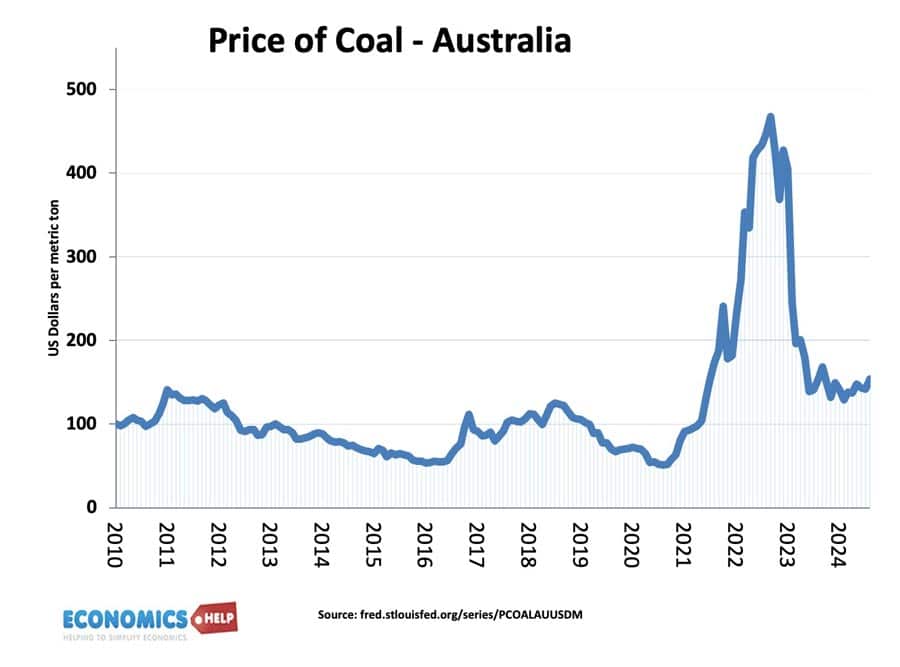

Even the global credit crisis didn’t hold back the Australian economy. Australia’s wealth is largely dependent on natural resources – coal, gas, iron ore and gold. This means that when the global energy crisis hit, Australia was one of the few countries that had benefited from a boom in energy prices.

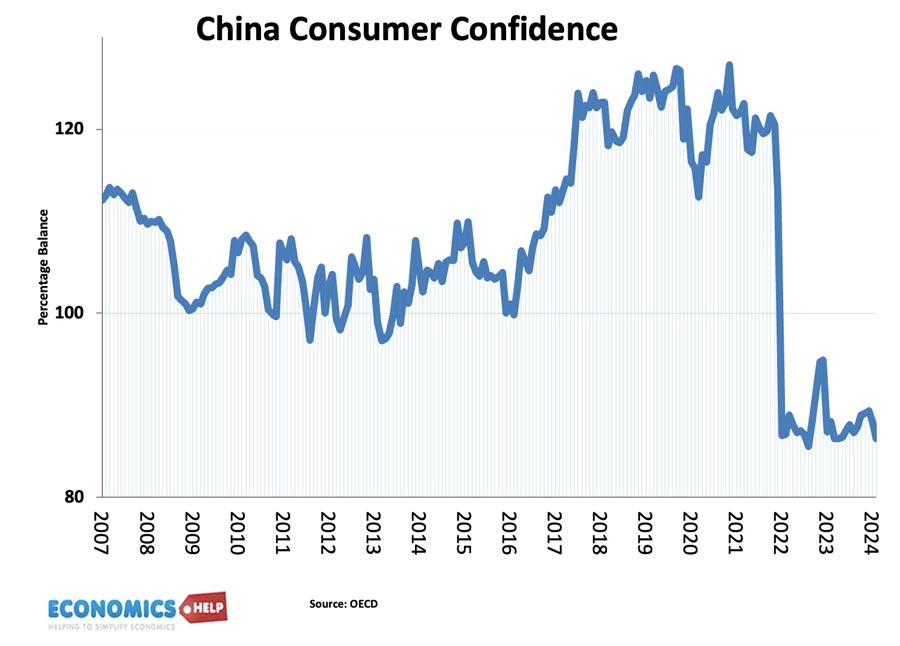

However as this graph shows, what goes up can come down. Australia has also benefited from a booming Chinese economy. China’s rapid growth has caused an insatiable appetite for Australian exports, in particular iron ore, the key component of steel. But, China’s recent economic slowdown is causing real problems for an economy which has relied on commodities for so much of the recent boom.

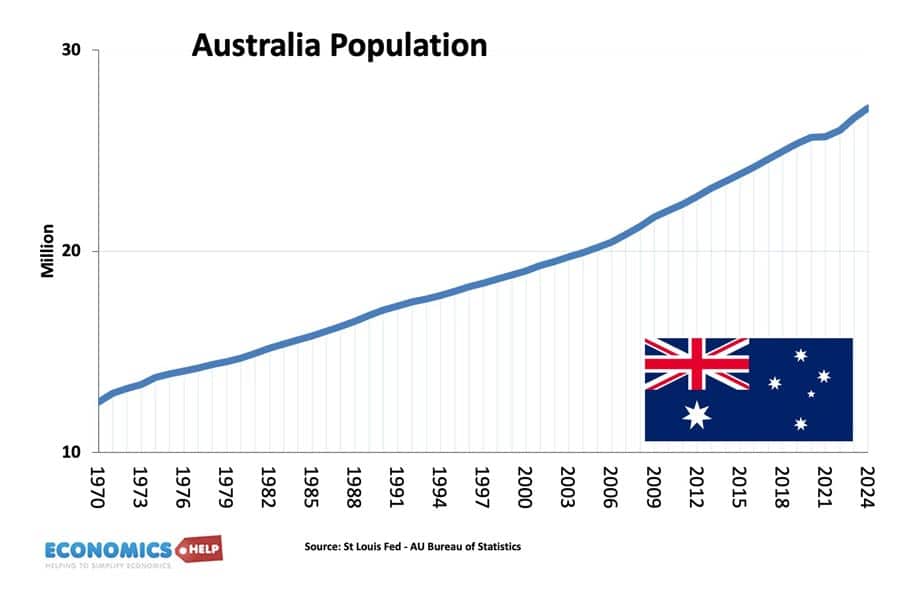

Impressive GDP figures may get economists excited, but how does this translate into living standards for average Australians? Well firstly, real GDP growth has partly been boosted by rapid growth in the population.

The Australian population has soared in recent decades, largely due to high levels of net migration. Migration helps delay the impact of an ageing population and boosts GDP, but if we look at real GDP per capita, it has been growing at a much slower rate, and this is important for determining living standards.

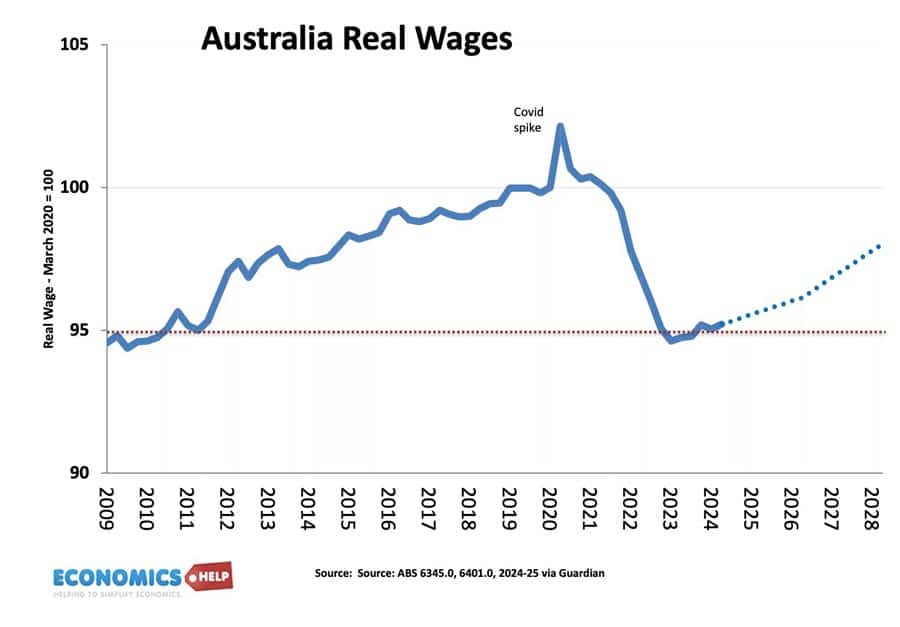

If we look at real wage growth, the pandemic saw a significant decline in real wages, taking living standards all the way back to 2010.

The government estimate real wages won’t regain the pre-pandemic level until 2028. This crunch in living standards is quite a shock for an economy used to high living standards. It hasn’t helped that inflation has been stubbornly high, requiring interest rates than the past decade. This has significantly increased the cost of mortgage payments. This is a problem because household debt is 183% of disposable income This debt reflects the rapid growth in house prices and need for households to take out big mortgages. This has distorted the economy and caused social unrest.

Housing Crisis

Whilst high housing costs is a global phenomenon, Australia is in a league of its own. In the worst affordable cities, prices are 13.8 times the median income, even in the most affordable cities, prices are still 6.8 times income. Almost twice as expensive as US. In 1990, house prices were 9 years of average earnings. Now, they cost 16 and a half years. That’s equivalent to an extra $167,000

Rents have also been rising through the roof. Affordability is the worst it has ever been, with 10% of Australians spending more than 60% of their income on rent. It has led to a housing crisis, with homelessness rates rising. And the biggest cause of rising homelessness is unaffordable rents.

High GDP, is not much use, if the average person struggles to afford the basics of living. Why did such a rich country fail to prevent this kind of housing crisis? Firstly, the population has risen rapidly, an extra 1 million people in the past 2 years alone, and house building rates have been nowhere near. Secondly, cities, especially Sydney have complex planning rules, which make it difficult for investors to build where demand is likely to be. Thirdly, the decade of ultra-low interest rates made housing a profitable investment and this was supercharged by government policy, such as the 50% discount on capital gains introduced in 2000. As affordability worsened offering grant for first-time buyers only spurred more demand. Rising prices, low taxes and low interest rates made housing an excellent speculative investment – especially since supply was not keeping up.

Earlier we mentioned that Australia is in the top 10 for GDP per capita, but this is massaged by the value of the currency, if we take into account the cost of living and actual living standards using purchasing power parity, Australia falls to 22rd

Problems of the Commodity Sector

The problem is that a strong exporting commodity sector has also created a relatively strong exchange rate, which pushes up the relative cost of exports. Behind Australia’s commodity boom is a shrinking of the manufacturing sector. Manufacturing has been squeezed by services and primary products. It is a mini-form of the resource curse or Dutch Disease. At this point, it is worth mentioning, that it could have been a lot worse. Many countries with similar commodity wealth to Australia have struggled to contain corruption and loss of opportunity. Australia has a relatively good track record in transparency and rule of law, even if many of the commodity giants are foreign-owned. Nevertheless, the reliance on commodities has a number of problems. Firstly, concerns over global warming are seeing demand for commodities like coal fall. Australia hopes that it will be able to boost new minerals like lithium and nickel used in battery electric cars have so far proved elusive. Demand for lithium has proved weaker than expected and many mines have scaled back operations. Australian producers also claim China has been flooding the market with cheap minerals. The reliance on fossil fuels, also highlight another potential problem, Australia is vulnerable to global warming, with record temperatures threatening agriculture and quality of life.

China Crisis

China is Australia’s biggest export market. More than one quarter of all trade is with China but it is an increasingly uneasy relationship. Political disputes, such as the origins of Covid have soured the relationship and whilst China is important to Australia, it doesn’t work the other way, with Chinese exports to Australia only a small fraction. Any trade war would hurt Australia more than China. But, at the moment, it is not so much a trade war, as a crisis in the Chinese economy. The property bubble has burst and the huge demand for Australian iron ore is falling. The problem is that when an economy is based around mineral extraction, it can be difficult to evolve and change. You can’t just magically reimagine a manufacturing hub.

Pros and Cons of Australia Economy

Australia’s economy has a number of problems. It’s large wealth is not satisfactorily being translated into higher real wages for ordinary households. The housing crisis is an existential threat. Yet, it is important to bear in mind, the economy still has certain strengths. It remains an attractive place to live. EIU rank Australian cities amongst the most attractive in South East Asia, Australians have a good living standard, they live longer than people in other anglophone countries, there is free government health care, but many have private insurance too. Deaths by road accidents, respiratory disease and firearm-related are noticeable less than the United States. The huge surge in migration has exacerbated the housing crisis, but it also reflects how desirable it is to live in Australia. Australia has the luxury of being very picky about migration, meaning there is less concern about low-skilled migration reducing wages for the unskilled. Australia even has lower geographical inequality, something which is a big problem with the UK and the US. Though the lives of Aboriginal Australians are more than 8 years shorter than average, though being less than 4% of the population it doesn’t have a big impact on the national average.

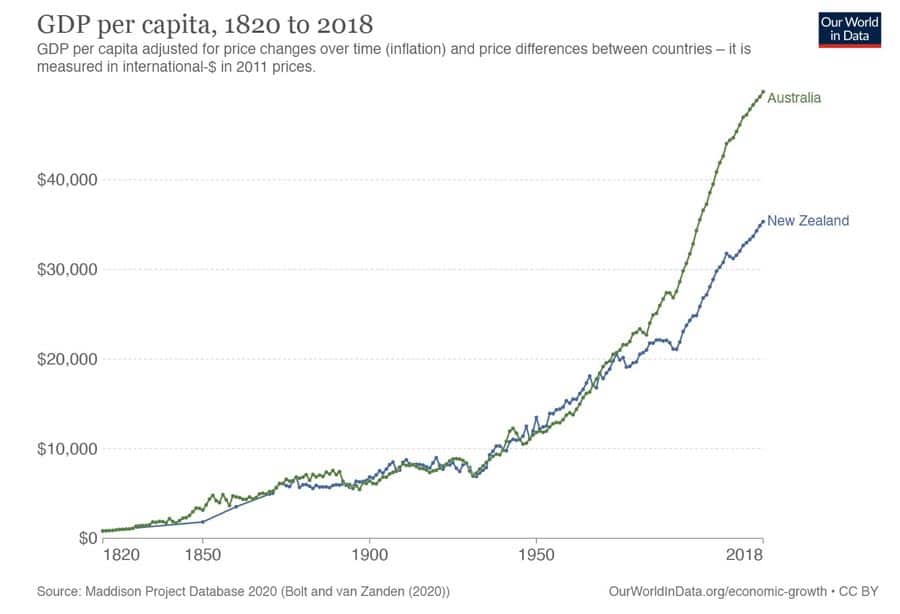

NZ vs Australia

It is also interesting to compare to the New Zealand economy. After the Second World War, GDP per capita stats were roughly equal, but Australia has grown at a faster rate. New Zealand is one of the few countries to have a crazier housing market than Australia. This has led to a consistent net migration of Kiwis to Australia of around 25,000 a year. Kiwis have moved with offers of higher pay, better working conditions and hope of cheaper housing.

Another country with similarities to Australia is Ireland. Ireland has even higher real GDP, but as this post shows a lot of it is an illusion which hasn’t improved living standards.

External sources