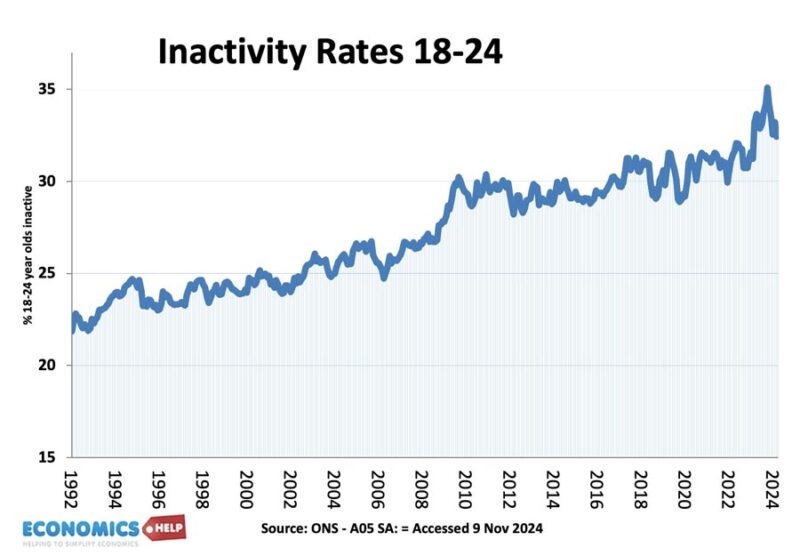

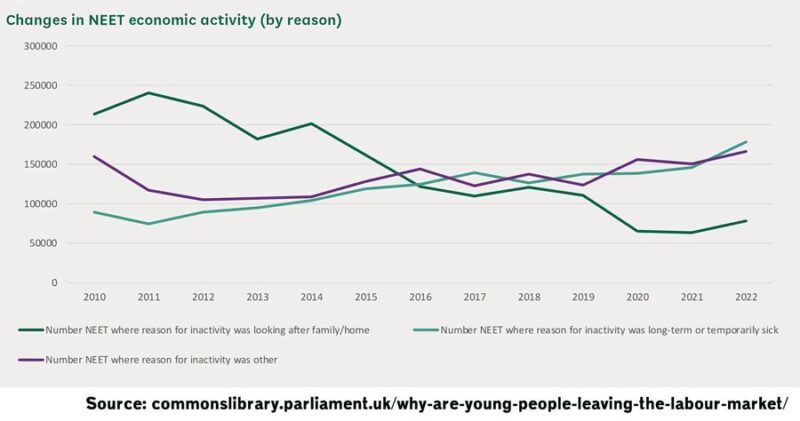

A record number of young people are giving up on work. Nearly a third of young people are either studying or dropping out of the labour market completely. In 2012 youth inactivity due to poor health was just 8%, now it is 23%, with poor mental health being the largest cause.

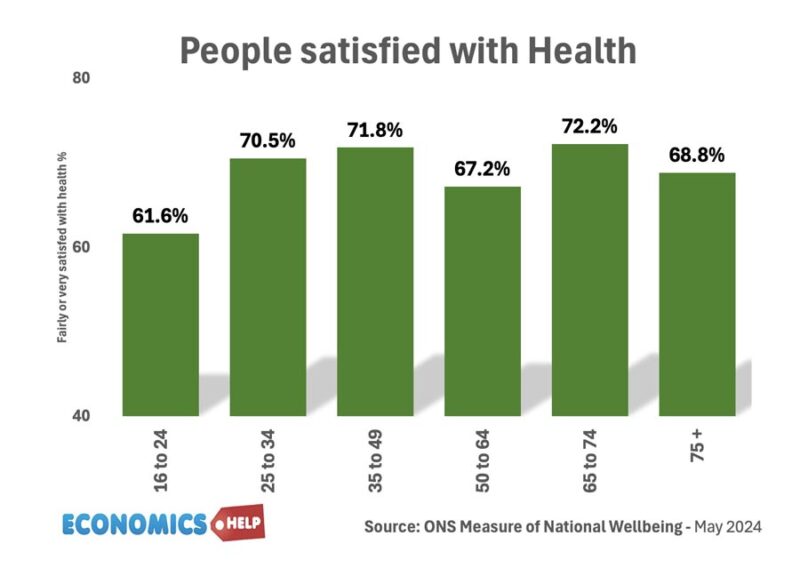

Amongst all age groups, it is young people aged 18-24 who report the greatest dissatisfaction with ill health and this is the biggest concern – young people not in work, but not in education or training either. And it’s not just about inactivity, Gen Z have different attitudes to work, with a rise in work disenfranchisement and and new trends such as lazy Mondays, hush trips, and just not turning up. Since 2019, there has been a 55% rise in the number of days taken off sick, and it is a major factor explaining the UK’s poor economic performance.

I have lost track of the number of employers who complain at the difficulty of employing young people. Flaky, entitled and lacking in motivation are some of the adjectives used to describe the younger workforce. But, generational contempt for young people is nothing new. In ancient Greece, the great philosopher Socrates was lamenting the youth for bad manners, greed and contempt for authority. Are the old work values of impressing the boss with long hours, even desirable? Could we learn from the younger generation about a better work-life balance?

Demotivation in Work

There is a growing phenomenon of younger employees who feel less connected and less motivated. Reasons for demotivation given include the gloomy economic outlook, rubbish jobs, a desire to move abroad and an awareness of better alternatives. In the past there was few alternatives to a classic 9-5 pm job. But Generation Z has grown up seeing people make a living from youtube, instagram and online sales. A content creator is more desirable than doing a so called “bullshit job” for other people. In this regard, I have some sympathy. I used to have a proper job teaching economics 45 hours a week. But, I wanted to spend more time cycling, so I gave up teaching and worked for myself creating a website and then youtube channel. It’s not particularly well-paid, I would probably earn more with a proper job. But, I love the freedom to work when I want. This could be seen as a positive aspect of the new work culture. Being able to say no to constant demands. Refusing to answer work emails outside work hours and a willingness to say no to tasks which are for show rather than productivity. The ultimate sanction is to give up on work entirely.

Covid

Covid and other cultural shifts have certainly created a new sense of freedom from traditional values. People are having fewer children and at a later stage in life – the need to settle down is being delayed. In fact, the rise in inactivity would have been even greater, if it wasn’t for the fact that young women are much less likely to be looking after children. In 2012, 45% of young women who were NEET was due to looking after children. In 2023, it is just 22%.

Disenfranchisement is exacerbated by the sense many jobs are insecure and low paid compared to extortionate housing costs. Young people renting their own place, can easily see up to 30 or 40% of disposable income going on housing. It is no surprise many have responded to the crisis by going back to live with their parents. The share living with parents has increased significantly in recent years. In fact there are reports young people turning down work due to the high costs of renting in big cities or cost of commuting.

Changing Labour Market

Another challenge young people face is a fast-changing labour market, which has seen some traditional jobs disappear and be replaced with either jobs with unsocial hours or high skill requirements which have left many unqualified. The Resolution Foundation report a strong link between poor health and low qualifications. 80% of young people who are inactive don’t have qualifications above GCSEs. Yet, with a cost of living crisis, 34% of NEET claim they can’t afford to study for the qualifications needed for their job. This is a real concern.

The share of young people aged 17-19 with a mental disorder rose from 10% to 26% between 2017 and 2022, and this is a major concern. Two-thirds believe the rising use of social media is a factor. Too much comparison, intrusion and sense of judgement are exactly the kind of factors that can feed into stress. Younger people themselves are more likely to blame not social media, but economic stresses. This includes factors such as rising housing costs, but stagnation in real wages. It is true that previous generations had a very reasonable expectation that things would get better, real wages would rise, and they would be able to afford a house. Yet, for the new younger generation the goal of homeownership seems a pipe dream given the ratio of house prices to income are near record levels. For a graduate with student debt of £45,000 saving an average deposit of £47,000 is very challenging without parental support. On the one hand, you could argue challenging economic circumstances would encourage people to work more, and there are in fact some who juggle multiple jobs to make ends meet. But, on the other hand, there is another section who find themselves economically inactive. The increasing stringency of unemployment benefits may be behind some people squeezing themselves onto health-related benefits.

Are Young Workers More Flaky?

What about the flakiness of young workers? Several employers have said since Covid, young workers are much more likely to phone in sick. This is backed up by evidence which shows a 55% rise in the number sick days. The one million dollar question is whether this is because of actually declining health or different expectations. A friend who works in a university says students are much more aware of how to gain extensions for their essays by using excuses such as family deaths, stress, and illness. Whilst quite a few are genuine, there is also a sense that many know how to game the system. A manager at a bookshop admitted he dreads employing students, because of too many bad experiences where they don’t show up, using a similar excuse to why you can’t do an essay.

There’s no doubt that the whole Covid episode was a shock to work and expectations of work. Firstly, long-covid and growing waiting lists are a factor behind growing ill health. Secondly, the shift to working from home has proved surprisingly difficult to reverse. Once you have a taste of working from home and having online meetings, it can be hard to go back to the time, difficulty and expense of so much commuting.

Yet, when we talk about Gen Z being difficult and wanting to stick to work boundaries, is this laziness or an awareness there is a better way of doing things? Certainly in the past many jobs had a strong ethos of working very long hours and doing everything that was asked because this was seen as the way to get ahead. Gen Z may be more able to see through this as a false way of just appearing to be willing. Rather than spend hours in pointless meetings, they have the aspiration to make a more meaningful contribution and if they can’t find it in a corporate environment they will look for it elsewhere. Gallup research in Japan earlier in the year found just 6% of employees feel engaged at work in Japan. This is a society which has long culture of very long hours, often with little point. Some jobs in the UK have similar patterns, and the desire to avoid death by overwork is strong. A report by WHO found that 745,000 people died in 2016 from stroke and heart disease related to overwork. If you already have poor health, who wants to exacerbate it with bad work.

The real reason for rising inactivity includes positive trends such as a willingness to avoid wasteful work and meetings and not to be taken advantage of. More worrying is the rise in mental health-related illness, which is difficult to precisely understand.

Sources