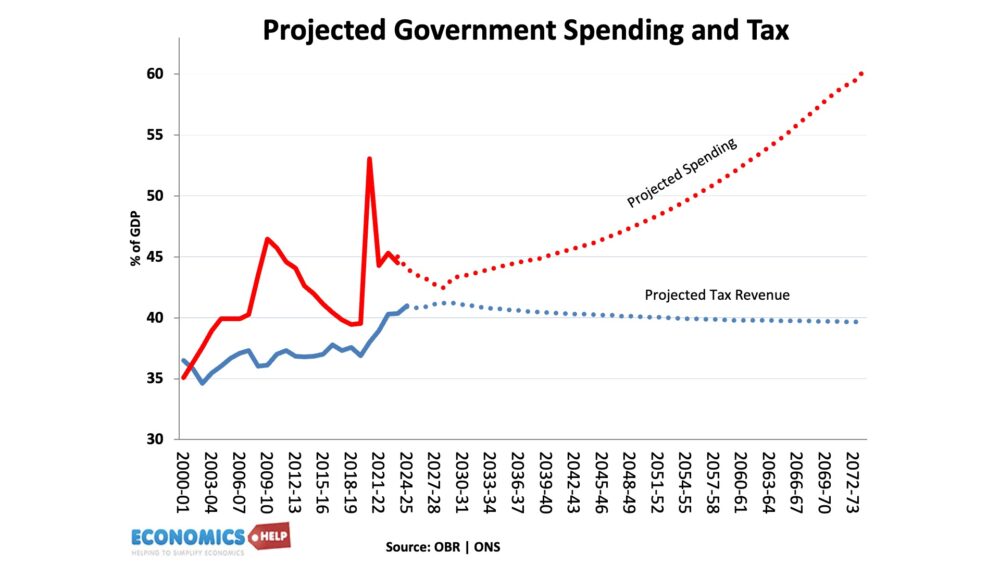

Recently the ONS produced a long-term forecast for spending and taxation. It makes for grim reading. Assuming policy doesn’t change, they forecast UK debt will rise to levels last seen in the Napoleonic Wars.

This forecast also assumes there are no external shocks like Covid or the Ukraine war. At the same time, bond investors warn of rising gilt yields and claim any further rise in debt could trigger another Truss-style meltdown in the bond market. Even Labour ministers defended the winter fuel cut on the grounds we have to worry about the bond market. Do we have any option other than austerity?

Firstly, we have to be wary of placing too much emphasis on the opinions of bond investors and financial analysts. As the FT notes, bond investors financially benefit from austerity. Austerity caused gilt yields to fall and bond prices to rise. Bond investors are one of the few groups of people who benefit from a stagnating economy. Strong economic growth can paradoxically cause bondholders to lose value.

But, how do you deal with the current situation of high-debt and low growth? How can you reduce debt without causing lower growth, like the 2010s? Arguably This is the wrong question to ask. The best question to ask is how we can achieve sufficient economic growth to reduce debt. After the First World War, the UK government imposed austerity on public spending and combined with overvalued exchange rate. It caused high unemployment and deflation. Public debt only fell slowly despite spending cuts and primary budget surpluses. After the Second World War, debt was even higher, but rather than panic and cut spending, the government invested in health, housing and a welfare state. The strong growth of the post-war period, enabled debt to fall dramatically over the next few decades.

The Truss debacle definitely affects Labour’s thinking. Their worst nightmare is being tarnished with the same brush of economic incompetence. But, it is important not to draw the wrong lessons from the mini-budget. At the time of the Truss budget, inflation was 10% and interest rates were rising sharply. The £100bn splurge of borrowing for tax cuts were inflationary, unfunded and very badly timed. It was reckless, bordering on the crazy. But, although the present government inherited terrible public finances, the economy is now very different. Inflation has fallen below 2% and interest rates are set to fall. This decline in inflation is real lifeline for the chancellor.

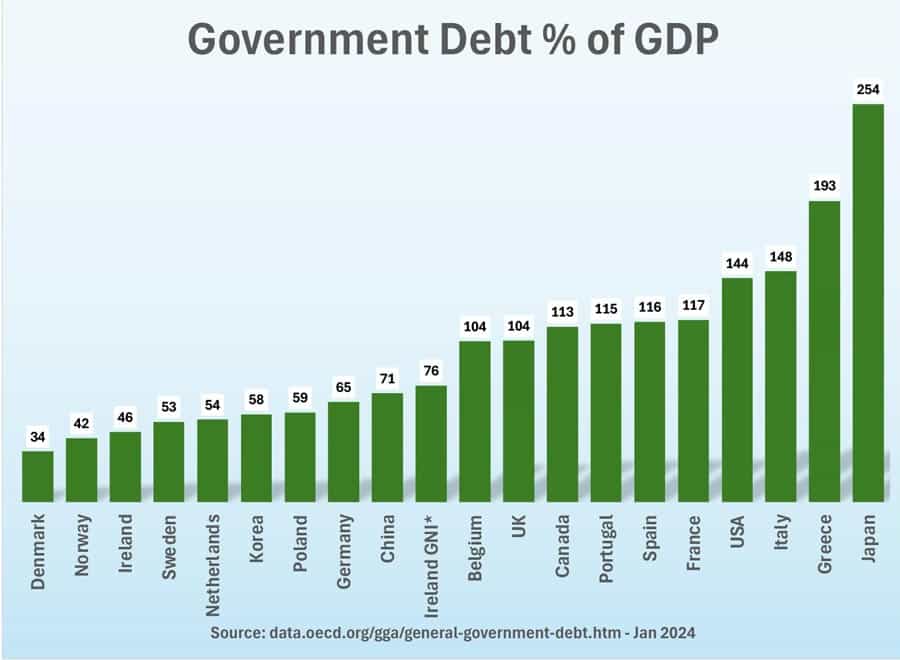

Also, debt as a share of GDP only tells part of the story. Japan has a debt of 250% of GDP but bond yields of less than 1%. High debt is not necessarily the end of the world. From 1997 to 2022, the average Argentinian government debt to GDP ratio was 68.42%. but they have seen five defaults in the past 60 years.

Public Sector Net Worth PSNW

It also depends on which debt measure you use. An interesting concept is public sector net worth PSNW. This attempts to look at both liabilities and assets. For example, if you borrowed to fund pension benefits, the public sector net worth would fall because you add liabilities but don’t get assets. This borrowing is more unsustainable. If you borrow to fund investment, public sector net worth could increase because the assets and potential future tax revenue is greater. This is why not all fund managers worry about borrowing for investment. Investment in capital stock increases the future capacity of the economy. That means future tax revenue to pay debt interest payments.

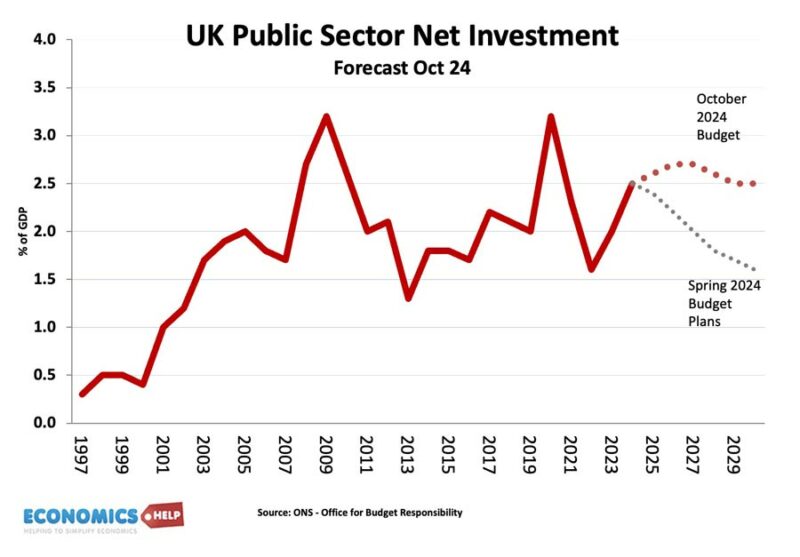

Is Britain Broke

If we go back to the question is Britain broke? The real problem is a lack of capital investment. Since 1990, UK investment has been 3 percentage points below the OECD average – a gap of £25bn a year. A report by EY put the UK’s capital gap in the region of £1.6tn. Yet public sector investment is expected to continue falling to just 1.7% of GDP in the next five years. Yet, under current fiscal rules, investments that increase illiquid assets like houses and schools do not show up, so chancellors wanting to meet debt targets have an incentive to cut investment, even though this has damaged the long-term potential.

If the UK invested in housing, power generation and transport, this would improve the long-term prospects of the economy. The OBR claim a permanent 1% increase in public investment increases potential output 0.5% in five years and 2% after 10 years. The return from investment is greater than borrowing costs. The real mistake of UK policy in recent decades has been short-termism. Worrying about the reaction of bond market, political giveaways and ignoring the decline in long-term capital stock.

A better question is can the UK afford not to invest? Under-investment can be expensive as we saw with high energy prices causing pain for businesses and households. Even something as simple as not fixing potholes can cost £14bn in repairs, accidents, and time wasted. Austerity can be expensive.

UK can never go broke

Another perspective on UK finances is from the MMT school of thought that the UK can never go broke because it has its own currency and the Bank of England has the ability to create as much money as it wants and fund government spending directly or through some kind of money creation or reformed QE. This is true to some extent, the government can increase the supply of money. In the 2010s, a large part of debt was being financed by the Bank of England. But, if there is a magic money tree it can also give the unwanted gift of inflation too. If the government started to finance its current budget through money creation you would start to see inflation, and it would end up being a default by stealth. In the 2010s, inflation was unusually low and there was scope for increasing money supply without inflation, but the return of inflation, made it less feasible. Basically inflation is a constraint on borrowing and money creation.

The government are likely to reform budget rules to allow more borrowing for investment but try to fund current spending through current receipts. This has a certain logic. But, it does mean that we face the prospect of austerity in some government departments. The problem is the government accepted previous unsustainable NI cuts, and ruled out major tax rises, meaning they have to scrabble around for tax revenue from inheritance tax, and capital gains, which are tricky to raise large sums.

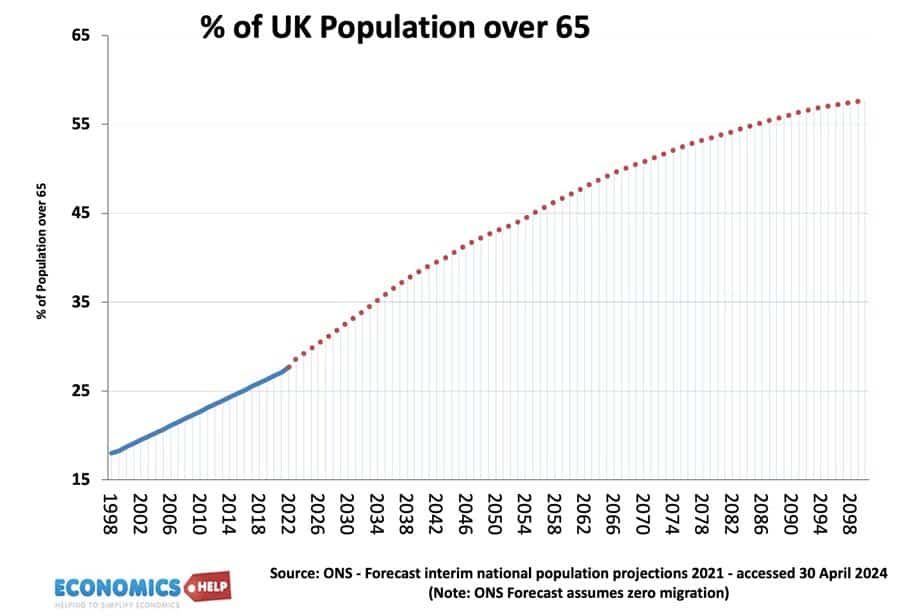

The government do inherit a bad fiscal situation. The last budget assumed real cuts in departmental spending. No wonder Ministers are starting to panic. In 2010, there may have been some fat left to trim, but today there isn’t. Many unprotected departments have seen big cuts in the past 14 years. Housing, education, justice, prison. The crumbling legal system needs a big injection of cash. The health care system has near-record waiting lists, but demand is expected only to grow in the coming years due to the ageing population, greater expectations and more treatments available. As a share of GDP, health care will continue to consume more resources and we can no longer accommodate this by cutting defense.

Ageing

The population is also ageing which will cause more pension spending. Amidst the furore over winter fuel payments, which saved only a very small £1.5bn, due to the triple lock pension benefits are forecast to rise 4.1% compared to working-age benefits, which will rise only 1.7%. But, as society ages, the budget position worsens. Even the post-Brexit immigration is less helpful to finances than it used to be.

Recently I made a post about the reasons to be slightly more optimstic about UK economy. There are signs that some things may improve, but even the most optimistic growth forecast by the OBR are fairly muted 1.5% a year possibly 1.8% a year. Whilst this is better than stagnation. For households, they are unlikely to see much increase in real disposable income. Housing costs keep rising and real wage growth is limited.

It is a mistake to cut back on investment to meet fiscal targets. This kind of austerity has damaged the UK’s long-term growth prospects and it would be a mistake to keep repeating the same blunders. But, the unwelcome reality is that even though the economy marginally improves, public finances are in a bad situation. The need for public spending keeps rising faster than tax revenues. Therefore, many will feel the continuation of austerity in both stagnating real incomes and in the provision of public services and working age benefits.

Is there an alternative? Yes. In the long-term, investment, planning reforms and pro-growth policies can increase growth giving chancellors more fiscal headway. In the short-term, if we want bigger state to meet the growing demands of an ageing population, higher taxes will also be needed.

With all this austerity, how can you justify a more optimstic outlook? These are arguments for optimism, even if some are not particularly convincing and rather hopeful.

Did not the average Brit face austerity in the late 1940s, what with widespread food and energy (coal mainly) rationing? The Atlee government panicked over the £sterling US$ exchange rate and tried to boost exports at the expense of the domestic economy. Yes, it worked in reducing the debt but please do not ignore the widespread pain imposed by the Labour government on the population.