In 1957, the British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan proclaimed to the electorate “You’ve never had it so good”. And he had a point, full employment, a growing economy, debt falling rapidly, record house building, rising wages, universal health care and a growing sense of optimism that things would keep getting better. But, can you imagine a politician trying to say the same thing today? We live in an era of performative misery. An economy that has stopped growing, falling real wages, a housing crisis and record homelessness, 7 million on waiting whilst the nation’s health deteriorates.

But, do we overestimate how bad things are now and how far we have come?

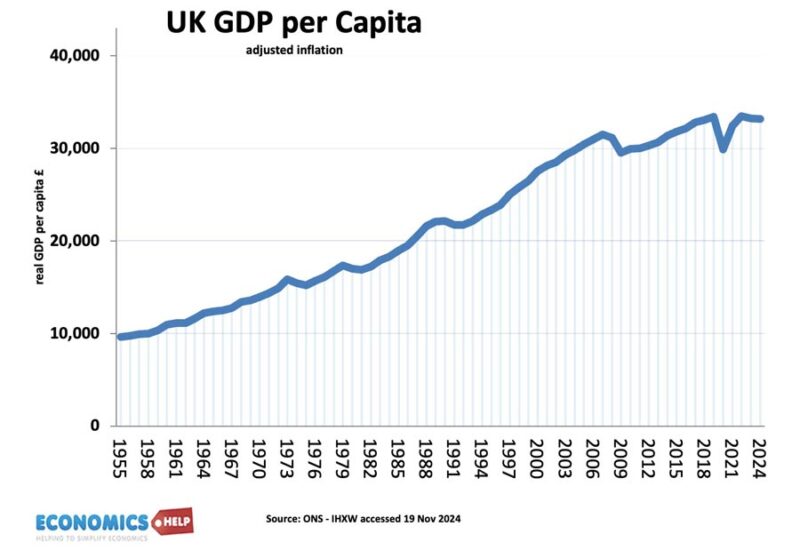

If we look at economic statistics there is no doubt, real GDP per capita is over 300% higher than 1955.

That means, in theory, average incomes should be three times higher than the golden age of the 1950s. In 1960, Parliament reported an average weekly wage of £14 2s. 1d for a 48 hour week. In today’s money that is an annual salary worth £14,290 in today’s money. By comparison, the average salary in 2024 is £36,000.

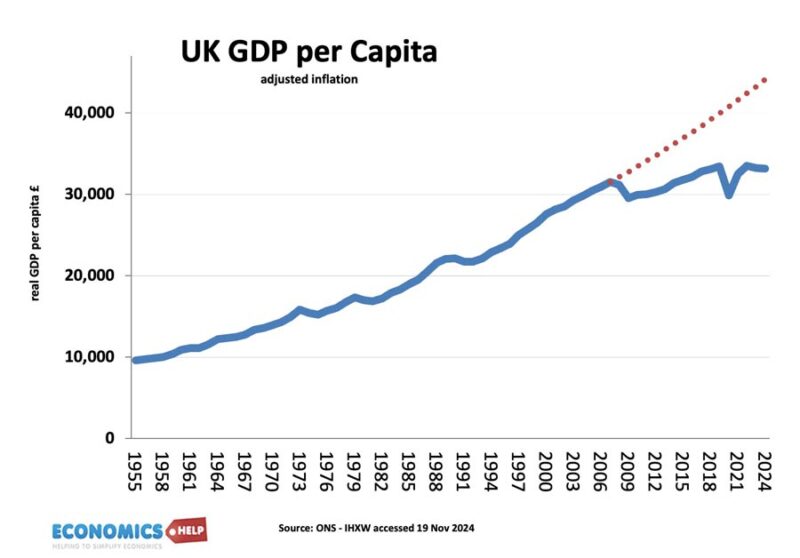

Yet, if we drill in closer, we see an interesting development. In 2007, the UK lost its past growth rate. If the economy had kept growing at its post-war rate of 2% a year. The average person would be £11,000 better off. In the 1950s, there were still living memories of the great depression, real poverty, no benefits, mass unemployment, even memories of the workhouse, the ultimate fear of the working poor. By contrast to this era, people felt rich compared to their parent’s generation. But today, there is greater focus on the fact this growth which we took for granted is now grinding to a halt.

Comparison to others

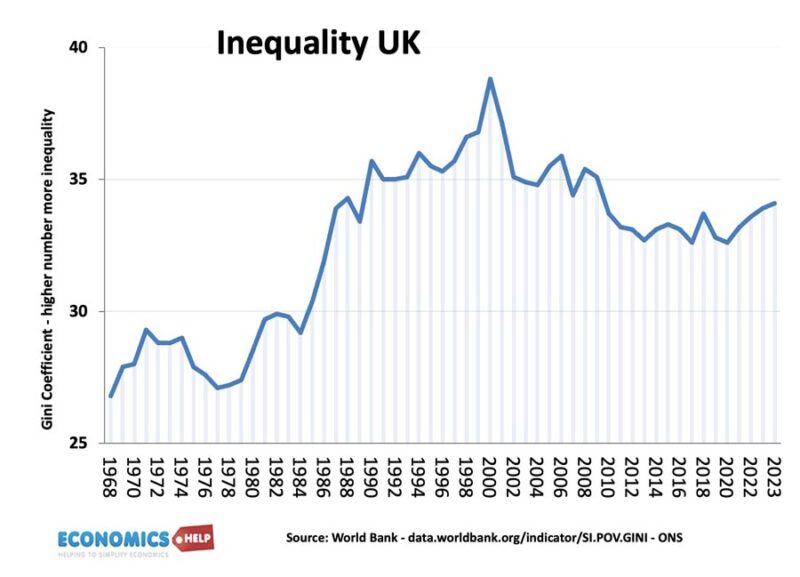

Our sense of well-being is often determined by how do we feel compared to other people? If we are struggling to pay rent, whilst the wealthy get richer it makes our relative poverty seem worse.

Certainly, since the 1960s, inequality has sharply increased. It was primarily the Thatcher era of the 80s, which saw growing income inequality. And this has been entrenched by rising wealth inequality, especially with regard to housing. Going back to the 1950s and 60s, there was still a legacy from the war effort, where we were all in it together. The sense of national crisis led to a very progressive taxation system, with high marginal tax rates on income and wealth. In recent years, austerity has led to a squeeze on benefits for low-income groups, leading to some of the highest poverty levels on record. However, poverty is still a relative thing. The idea that the 1950s was an era of universal prosperity is deeply misleading. Even in the 60s, The UK still had significant levels of slum housing and real poverty. Many households still didn’t have central heating but struggled to make ends meet and stay warm. Life was a struggle, especially given that many households usually only had one wage coming in, but more children. It is more expensive to bring up children today, but we are having fewer of them. Housing was relatively more cheap in the 60s, but there was still a homelessness problem. In the late 60s, Ken Loach’s film “Cathy Come Home” was a fictionalised account of the homelessness faced by young people and the shocking reality of how young woman could have their children taken away because of economic misfortune.

Labour Saving Devices

One of the biggest economic revolutions of the past century was labour-saving devices for households. It is estimated that the humble washing machines have done as much to boost productivity as the internet. Even in the 1970s, many women would take their laundry to a public washroom. Several hours a day needed to be dedicated to tasks such as laundry, shopping and household cleaning. The rise of labour-saving devices we take for granted, but it has freed up hours of unpaid work, and this has been a big factor in increasing female participation rates in the labour market. In 1951, female participation in the labour market was just 39% today it is 72%. Bear in mind, that this unpaid work was not counted in GDP, but was real drudgery. Nowadays, we don’t even have to go shopping. I often get my groceries and shopping delivered to the door, it is effectively more time that I can spend earning $10 an hour posting videos to YouTube…

More products – better quality of life?

Also, today we have a much greater choice of products than in the past. Until 1982, there were only 3 tv channels in the UK. And Most of it was rubbish. You couldn’t watch YouTube videos on how to mend a broken watch. Even in the mid-1980s. I remember watching the snooker on my grandmother’s black and white 13” tv screen, which took minutes to turn on. Today, we have access to just about anything you could be interested in. Perhaps the problem is more a surfeit of information and a deluge of social media that is affecting people’s mental health.

But, whilst this atomistic existence of the social media age might boost productivity, is the modern internet age losing its sense of community? Even if I do go to Tesco, I use self-checkout scanner and don’t really talk to anyone. At least the washerwomen had a sense of community that is perhaps being lost today. Certainly, work patterns are shifting. The traditional work class jobs like mining, shipbuilding all fostered a sense of close-knit community, which is missing in the zero-hour contract, deliveroo economy. Certainly, for many former mine towns, the closure of industries which once dominated a town led to a fracturing of community, a rise in social problems and less sense of pride in work. The kind of community spirit that cannot easily be measured in monetary terms.

Who wants to be a miner?

But, even with this – is it a mistake to romanticise the old working-class jobs like steel workers and coal miners? The reality of coal mining is that it was dirty, dangerous, hard work and left miners with ill health. If you had to choose between a career working in a call centre and a career working as a coal miner, which job would young people choose? In 1950, there were 700,000 people employed in the coal industry is it such a bad thing this is no longer the case?

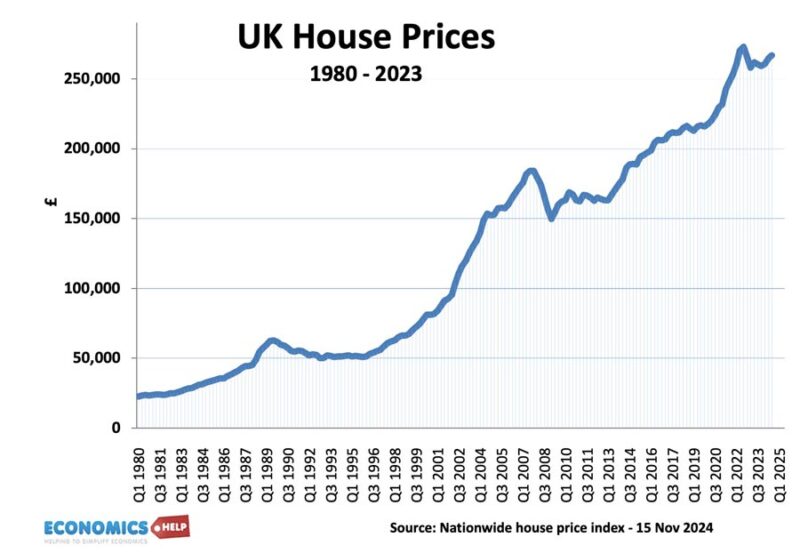

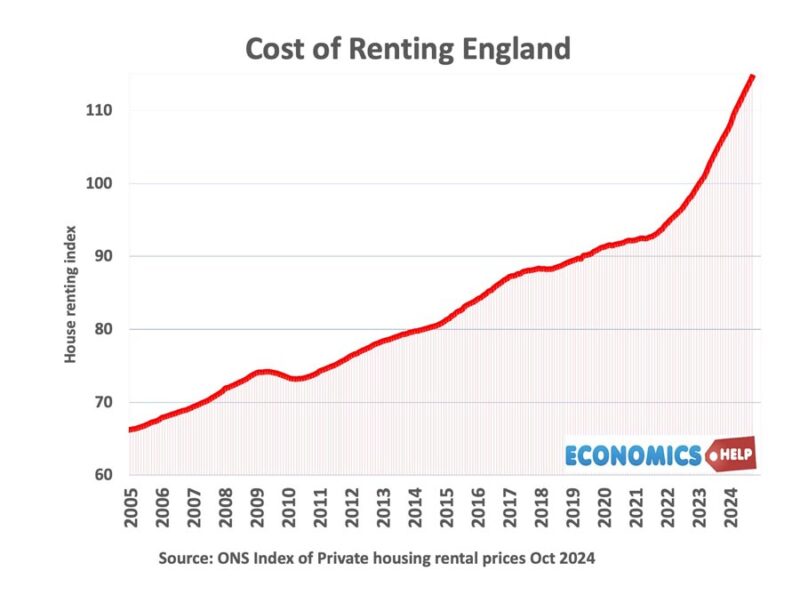

Housing Market

One of the biggest failures of the modern economy is the housing market. In many ways, young people are facing a much tougher situation than their parents. For much of the post-war period, house prices were 3-4 times incomes – in other words affordable. Even workers on modest salaries could afford to put down a deposit and get a mortgage.

Household budgets may have been tight, but the ability to buy your own house is a huge economic, social and psychological bonus. The problem for young people and some old people is that the housing market is now out of reach. House prices eight times income is unrealistic unless you are really high earner or your parents can help you out. The alternative is to spend a very high share of your income and rent. And it is not just the negative impact on living standards but also the perceived unfairness. Buying a house is increasingly down to whether your parents have wealth themselves. The home-buying meritocracy of the past has been lost. The situation is even more grim for low-income groups who used to have greater access to council houses but recently have become more scarce.

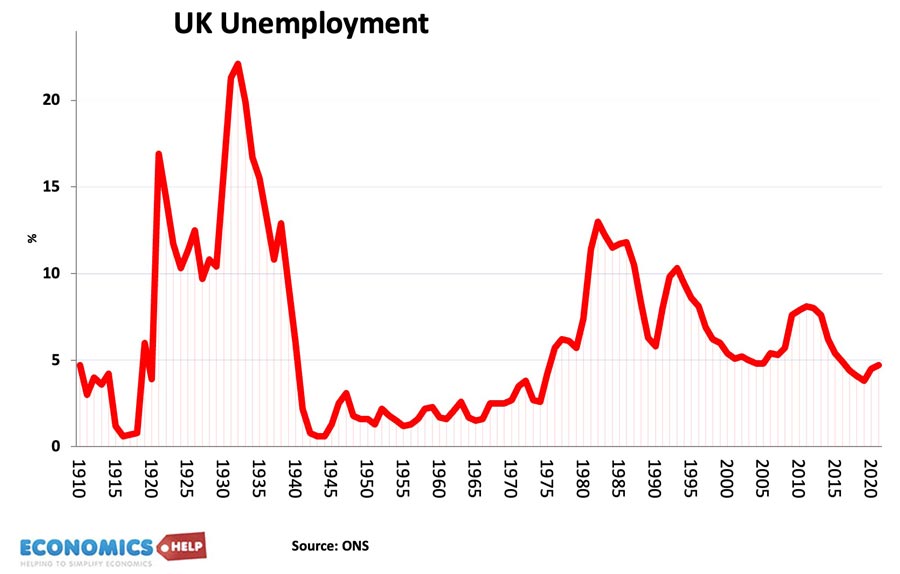

Low Unemployment

A big benefit of the current economic climate is low unemployment. Jobs may be low-paid, insecure and even part-time, but in the past, we have had periods of mass unemployment which is devastating for those affected. Unemployment is psychologically the greatest economic cost to those affected. Unemployment was worst in the 1930s, when it reached real crisis levels But, for much of the 1980s and early 90s, it was also close to 10%. Full employment is an achievement which gets relatively little mention, but the past periods of high unemployment were a major downside.

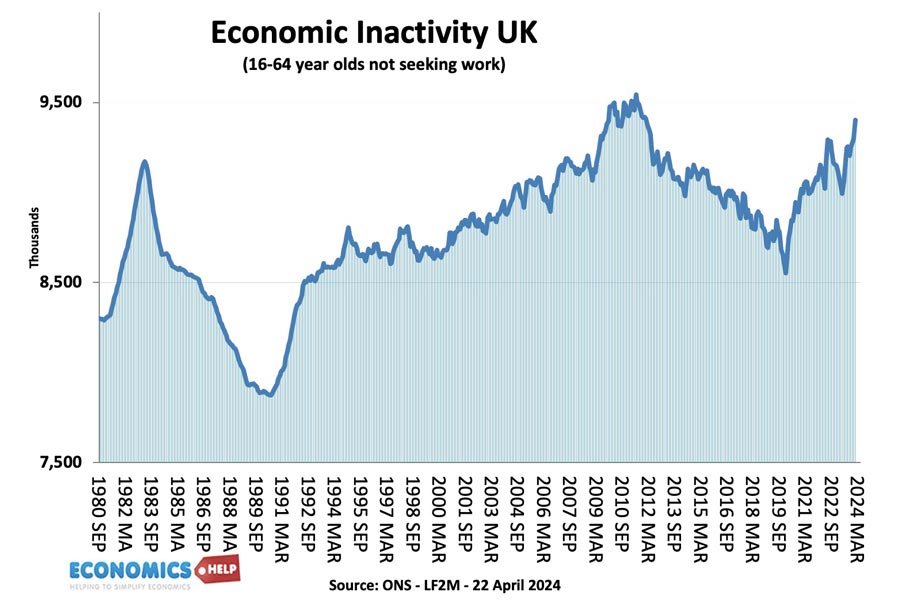

Inactivity

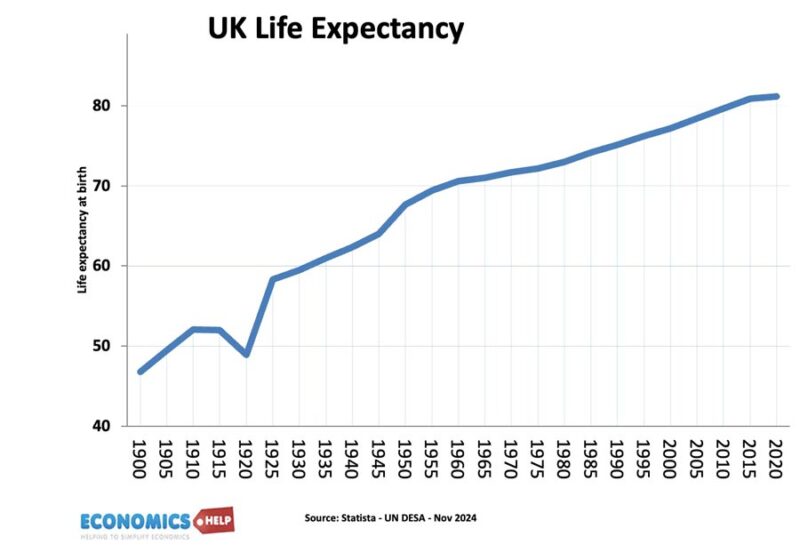

The modern-day problem is not so much unemployment as growing inactivity. In particular, there has been a worrying rise in long-term sickness, especially since Covid. However, recent problems aside, a really big boon of the past five decades has been an increase in life expectancy. In the UK it has risen from 67 in 1950 to 82 in 2020. This is a remarkable achievement a reflection of better health care, better treatments, better nutrition and reduced child mortality rates. An indicator of how the nation’s health has improved is the dramatic fall in infant mortality from 29.1 deaths per 1,000 in 1952 to just 3.4 today.

Life Expectancy

Yet, this increase in life expectancy has ironically created a headache for government finances. Combined with a precipitous drop in birth rates, all western societies are facing an ageing population, which is giving governments more difficult choices. In the post-war period, the government could spend more on health care and education due to economic growth and declining spending on defence. Not only were real wages rising, but public wealth was increasing with more schools, hospitals and doctors. Yet, government finances are now increasingly constrained by these demographic pressures. There is a real sense that not only is income stagnating, but the public sphere is struggling, with a fraying at the edges, longer waiting lists and shortage of money. This public sector decline explains the sense things are getting worse.

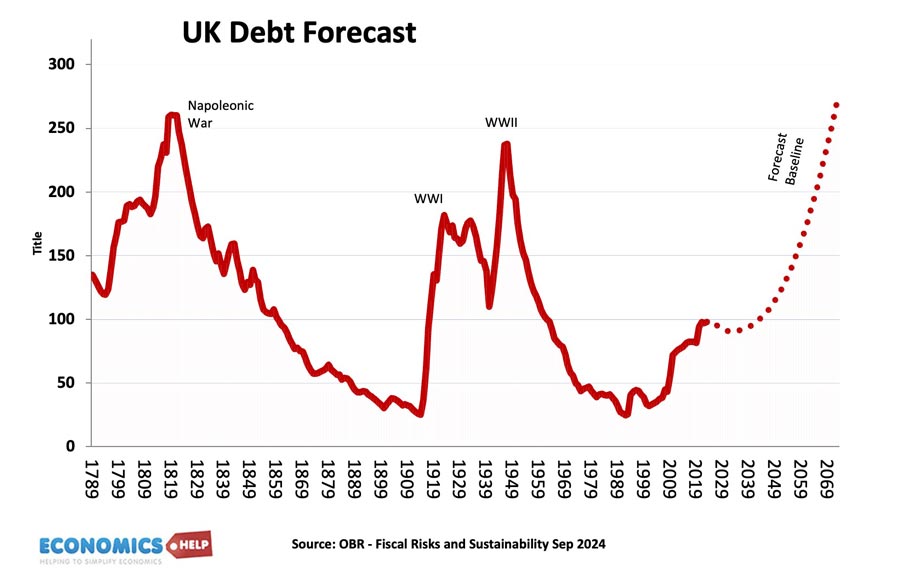

The change in fortunes can be seen by the trajectory of national debt. Peaking at 240% of GDP in the late 1940s, it fell steadily until the early 1990s. But has since risen and is forecast to keep rising because of demographic pressures.

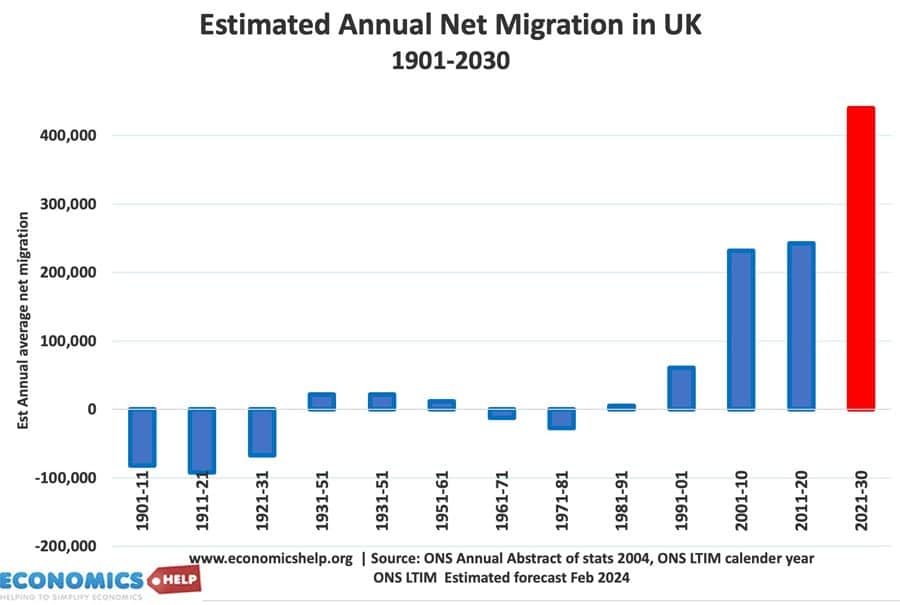

Partly due to the ageing population, immigration patterns have changed. Despite high levels of migration from the Commonwealth in the 50s and 60s, net migration was close to zero because many native-borns were leaving the country, often to Australia and Canada. The past few decades have seen a sharp rise in net migration rates, which has put upward pressure on housing costs even if some forms of net migration benefit the Treasury.

Environment

When we think of 1950s, we tend to think of bucolic countryside scenes but in 1952, London suffered from the Great Smog of London which saw the deaths of 12,000 people and many more suffering long-term health issues. The Clean Air Act of 1956 meant coal could no longer be burnt in cities and this went a long way to improving air quality. In the 1950s and 60s, coal was still king, and most of the rail network was powered by steam until the mid-1960s. But, the steady decline of coal means UK C02 Emissions have been declining, though there are still issues with more invisible pollution such as ammonia and nitrogen dioxides. Human-made pollution is estimated to kill between 28,000 and 36,000 people every year.

Health and Safety Gone Mad

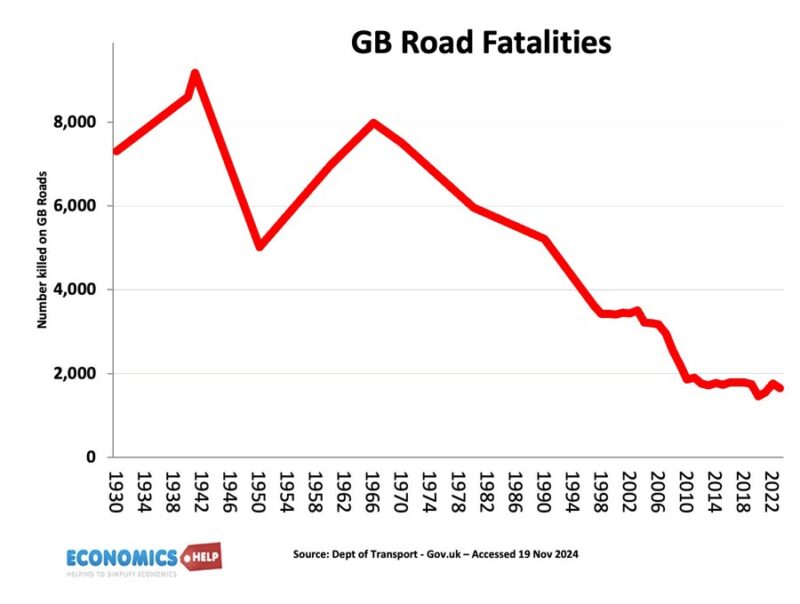

The 1960s could be seen as a golden era for driving. Empty roads, and new faster roads without the innumeral speed cameras, road humps and congestion we see today. But, even in 1961, 69% of households still did not have access to car. Today, that is just 22%, with car travel becoming the dominant form of transport and within reach of most people. Yet, despite a 600% rise in road travel since the mid 1950s, road fatalities have fallen sharply.

From a peacetime peak of 8,000 fatalities in 1966 to just 1,645 in 2023. Seat belts, speed limits, better car design have all played a role in reducing fatalities. It is a quiet boon of recent decades. There is much disquiet at new 20mph zones, but they will reduce fatality rates further. Slightly less good is the rising cost of public transport, with buses and trains seeing above-inflation increases. And despite growing transport bottlenecks the UK has definitely found it more difficult to build things. The flagship HS2 is symbolic of the very high cost and lengthy delays of building infrastructure today. Victorian navies built miles of railway every month. We spend years on just planning procedures. Whilst seat-belt legislation has a clear benefit, legislation to protect rare bats, cost an estimated £100m just for a custom built bat tunnel – no wonder HS2 ran over budget making it more difficult to ever build things again.

Education

In the post-war period, university education was the preserve of a small cross section of society. Usually male and high-income families. In 1952, just 23,000 women were at university. Today, it is 1.63 million women. The rise in student numbers has given much greater opportunities for young people that were previously closed. But, it has come at a cost literally – the cost of tuition fees, which was once virtually free are now £9,535. Unsurprisingly the average student debt in England has risen from barely nothing to £45,000. It means graduates face a marginal tax rate of 50% for any income over the basic rate, a high tax burden if you’re trying to save for an average deposit of £47,000. Whilst university education have gained increased prominence is it at the expense of vocational skills.

So are things better than in the past? Yes, on balance they probably are. And if you don’t believe me ask my Yorkshire grandfather. “Son when I was a lad we used to dream of living in a house… 16 hours a day down pit, and paying mine owner for privilege…”

Sources

A good summary of the changes over the last 60 or so years. Many improvements though certainly at the expense of a loss of sense of community. Can’t agree with the comment about television shows being better these days. The comedy shows of the 60s and 70s are classics – indeed I’ve lost interest in watching TV these days.

Of course the 16 hours down pit ended before WW1, thanks to, I believe, Lloyd George & Churchill and the Liberal Government of the day.

On the fil you refer to Cathy Come Home as a Ken Burns film. Should be Ken Loach. Enjoyed the very informative film – thank you.