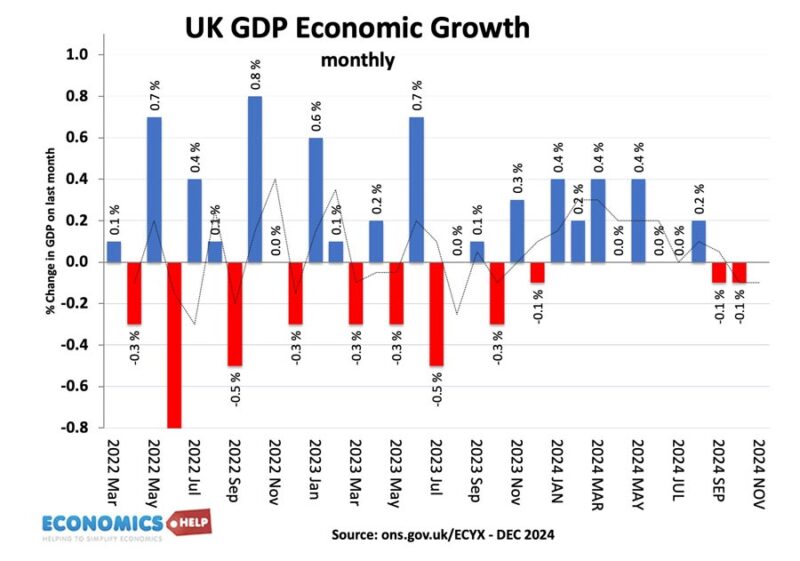

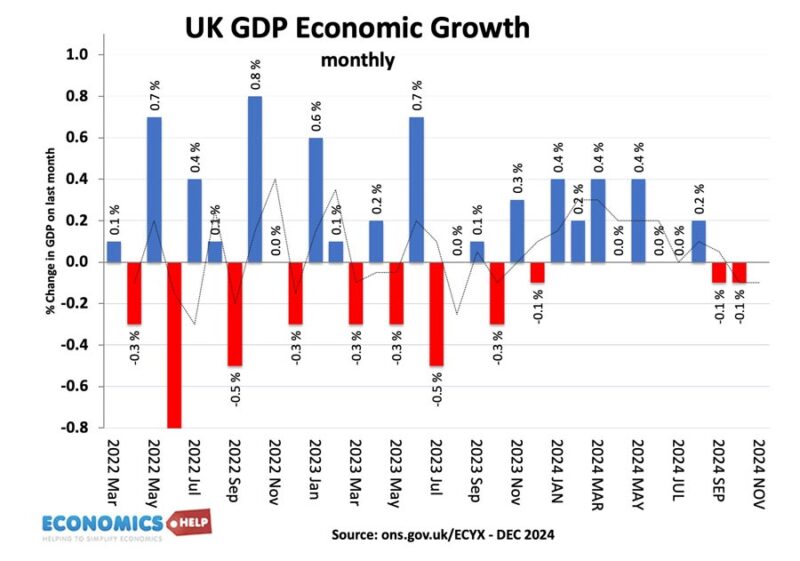

There’s been no honeymoon for the new Labour government. Since the election in July, UK growth has continued its long-term trend of barely existing. Recent data disappointed analysts with output falling in the last two months.

Monthly data is noisy, but it comes amidst business warning of a weaker labour market, with higher national insurance, and rising labour costs leading to a fall in job vacancies. The weaker growth has been attributed to concerns about the budget. It wasn’t helped by talks of budget black holes and need to make painful choices. It’s not surprising business and households are somewhat gloomy. It is too early to talk of a recession, but despite higher government spending, the OECD has already reduced its growth forecast for the UK for 2025 from 1.1 to 0.9%. Rachel Reeves is finding that wanting economic growth and achieving economic growth can be two entirely different things.

But, beneath the surface, of stagnant GDP growth, there are several worrying factors, which make the hope of strong economic recovery look increasingly pessimistic

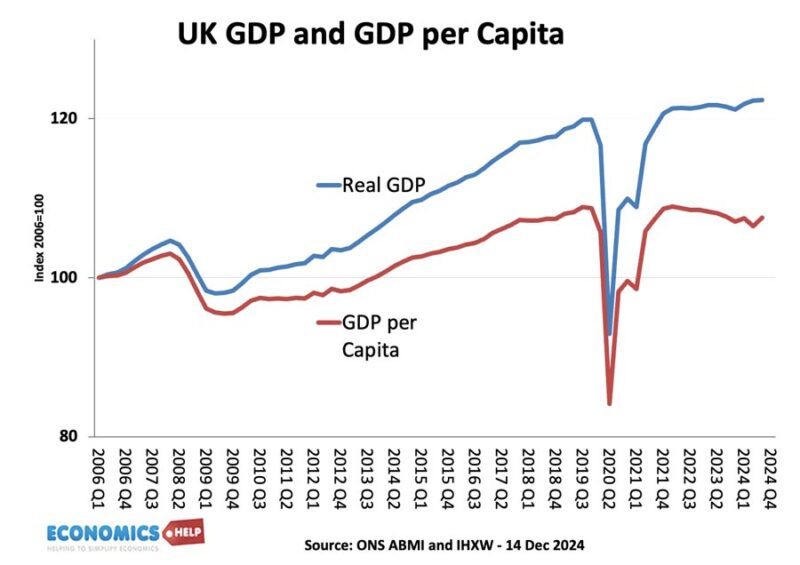

Firstly, GDP stats have been massaged by rising population, mostly due to high levels of net migration. Real GDP per capita has barely increased since 2007 and is still below the 2019 peak.

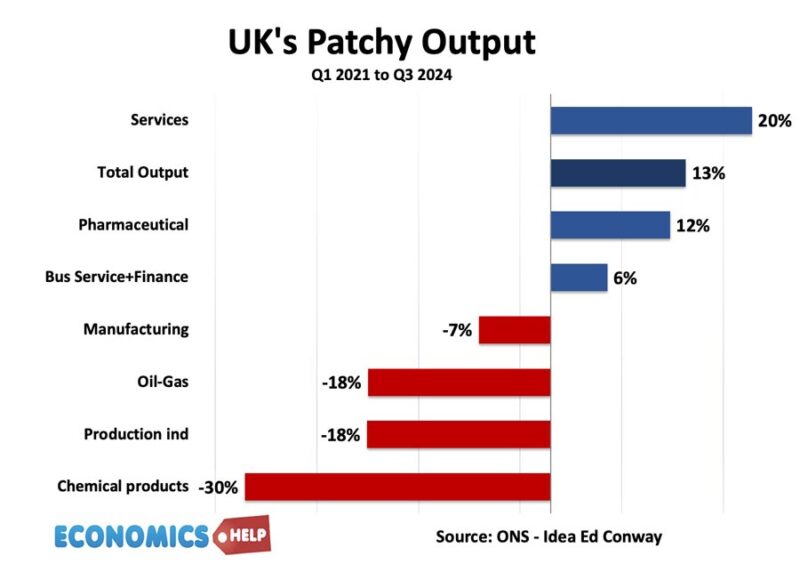

Secondly, if we look at the GDP figures beneath, we can see that some industries are in a clear decline. It doesn’t get much press, but the UK chemical industry is the UK’s top manufacturing exporter with £29bn of exports. In 2021, it employed a quarter of a million people and revenues of £75bn. But, since 2021, output has fallen 37%. Industrial and manufacturing output is also falling, it’s a new era of de-industrialisation. The difficulties in the steel and car industry are well documented. UK car production in 2024 is nearly half the peak in 2017, with exports of cars particularly affected. This decline in manufacturing makes the UK economy increasingly reliant on financial services and London service sector. But if anything the UK’s London-centric economy is more of problem than a benefit. In recent years, the FT report how the UK is becoming even more London Centric. 30 years ago, half of the top paying jobs were in London, now it is 75%. The UK is the only western G7 country where jobs are becoming more concentrated in the dominant region.

Most graduate jobs are still based in London, but rising rents has priced out many of the workers, the London economy needs. In the US and Europe, high paid workers have options other than capital city, But, London’s economy continues to dwarf the rest of the country.

Finance

Recently Rachel Reeves was in Brussels, asking for special treatment for the City of London. A strategy which given the UK’s recent Brexit history seems likely to get poor response from the EU, but it is the over-reliance on London finance, that is more of a long-term problem. Yet, desperate for growth, the chancellor is looking to relax regulations on city firms to be able to take more risks. The last time a Labour chancellor took a light-touch approach to financial regulation it ended up with with a big taxpayer bailout for the banks. The UK depends on jobs in London for income tax revenue. The top 1% of earners are now paying 29% of all income tax revenue, but relying ever more on finance for growth has drawbacks. The IMF produced a report that warned a large financial sector can have a negative effect on the economy when private credit is greater than 100% of GDP. In the UK, it is 160%, with only 18% of bank lending going to productive industries, the rest being mortgage debt and lending to the finance sector. And this is another concern about the state of the economy, a lack of lending to private firms, which is behind the falling investment levels in the UK. A more promising approach are the policies to encourage UK pension funds to invest in the UK stock market and regional banks focused on lending to business and infrastructure.

Deindustrialisation

One factor, behind the industrial decline is the fact UK electricity has become the most expensive in Europe. Modern industry is heavily based on electricity. Modern steel factories no longer burn coal, but use electricity. Massive data centres need reliable power sources. The government has an ambitious plan to invest in new energy sources. But, even if successful, years of under-investment in the national grid means it will be difficult to connect to where it is needed. Even housing construction in London has been delayed due to lack of electric connection.

Labour Productivity

The second underlying problem facing the UK economy is the backbone of the economy – labour productivity. This is a well known story – that since 2008, Labour productivity has gone from growing at 2% to growing at 0.5%. If this doesn’t improve, UK growth will always be constrained. Even if you boost demand by tax cuts and government spending, if productivity doesn’t rise, the boost in demand will just cause inflation. Even now, despite low growth, inflation is a bit stickier than policy makers would like. There is nervousness about cutting rates when the majority of goods are still rising faster than 2%. In 2025, homeowners will face even higher inflation rates as many remortgage from ultra-low mortgage deals of 5 years ago. Renters, face little let up in the cost of living crisis. Rents have risen 25% since 2021. And this is a really big problem. Even if the economy manages to grow and real incomes rise, they will be eaten into by housing costs. The Joseph Rowntree predicts that adjusted for housing costs, average household incomes could be £700 less than 2019, £700 less than 2024. The OBR is the most optimistic forecaster for the UK economy with growth of 2% pencilled in for 2025 and 1.6% for 2026. However, whilst respectable, once we take into account population growth and housing costs, it’s easy to understand gloomy predictions of living standards.

The third problem is that a lot of the government’s programme is based on increasing growth. They are relying on growth to avoid any more tax rises. They are hoping for growth to be able to improve public services. If growth doesn’t materialise, it will lead to more awkward choices in 2 or 3 years time. The problem is that demographic factors are set to really work against them. With an ageing population, we are set for much higher spending on pensions and health care, and that is just to stay still let alone get on top of problems like reducing waiting lists and preventative health measures to improve the worrying rise in sickness rates. And that brings us to another long-term problem of the UK economy. A rise in sickness rates and rise in inactivity. People leaving the labour market. Despite a slowdown in labour market, firms in many sectors still struggle to fill vacancies. The government want to build 1.5 million homes, which is a good target given the long-term shortage of housing, but do we have the builders necessary to build them?

If that sounds grim, unfortunately, the global outlook offers little source of consolation. If anything weak growth in Europe and higher tariffs from the US will mean global factors will hurt rather than help the UK economy.

Positive shoots of recovery

However, at Economic Help, we always like to look on the bright side of life, are there any optimistic shoots of recovery to hang on to. Firstly, although growth is very weak, it is too early to talk of recession. Growth of 1-2% for the next two years is better than nothing. If there is growth, it may see continued improvement in consumer and business confidence. Secondly, there is likelihood of some interest rate cuts next year, which will ease pressure on households and encourage investment.

Secondly, as mentioned before, UK households have actually been building up large reserves of savings. In other words, there is potential to spend more when they feel confident to. I’ve been saying this for a year, so there is no guarantee it will materialise, but some households at least have more of a buffer than usual.

Thirdly, last year was another record year for reducing battery costs. Batteries are increasingly important in consumer goods, transport and in future power supply. Technological improvements are consistently better than many people’s expectations. Solar, batteries, renewables are all getting better and cheaper and will continue to do so. This is the kind of thing which can improve productivity in the economy. Of course, the benefits is slightly reduced because they are not made in the UK, but imported from China. But, lower battery costs will at least offset the expected rise in food prices.

Fourthly, is the gloom around the new government and economy slightly overstated? Unemployment is low, growth should be positive next year and thanks to the minimum wage, low paid workers will see another pay rise in 2025. The media and youtube do have incentives to exagerates negative stories. I get the feeling some of the media are enjoying have a Labour government to blame everything on.

Conclusion

I’m not sure how convincing this optimism sounds, and the basic premise of a virtually stagnant economy does still hold. Very low growth is not enough to see material improvements in living standards, especially because the housing crisis sees no sign of abating. Will house prices continue to rise in 2025 or is there a chance they could fall? This video goes into more detail.

https://www.hse.gov.uk/chemicals/sectors.htm

https://positivemoney.org/update/how-is-bank-lending-shaping-uk-economy/

https://www.ft.com/content/1d1792fd-c6a0-48a6-8ec0-d49d6d1b27d2