It’s not been a good week for the UK economy with the Bank of England downgrading economic growth and upgrading inflation forecasts. We’re heading for stagflation, the worst of both worlds. If you wanted more bad news, the Bank of England warned that productivity growth may actually be even worse than the pretty dismal statistics over recent years.

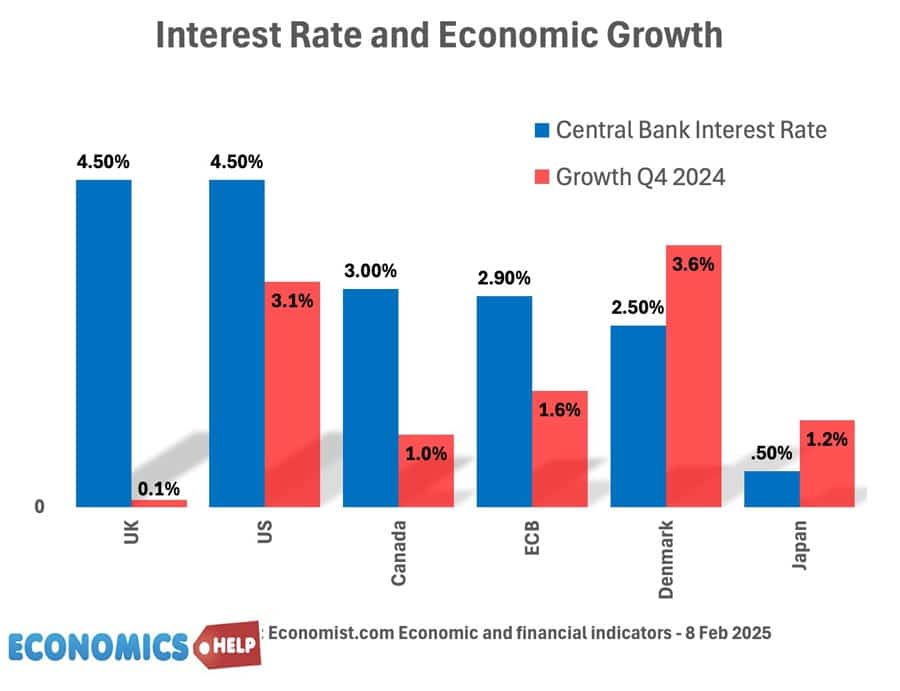

The Bank is not helping by keeping the tightest monetary policy in the G7. UK rates are still an anomaly at 4.5% – the highest interest rate but the lowest rate of growth. There are also signs firms are cutting back on hiring new workers over concerns over upcoming tax and higher minimum wages.

The economy in 2025 seems to be a continuation of the past 15 years. There has been some increase in real GDP, but if we take into account growing population, real GDP per capita is still below 2019 levels and this is the big concern, where is economic growth going to come from?

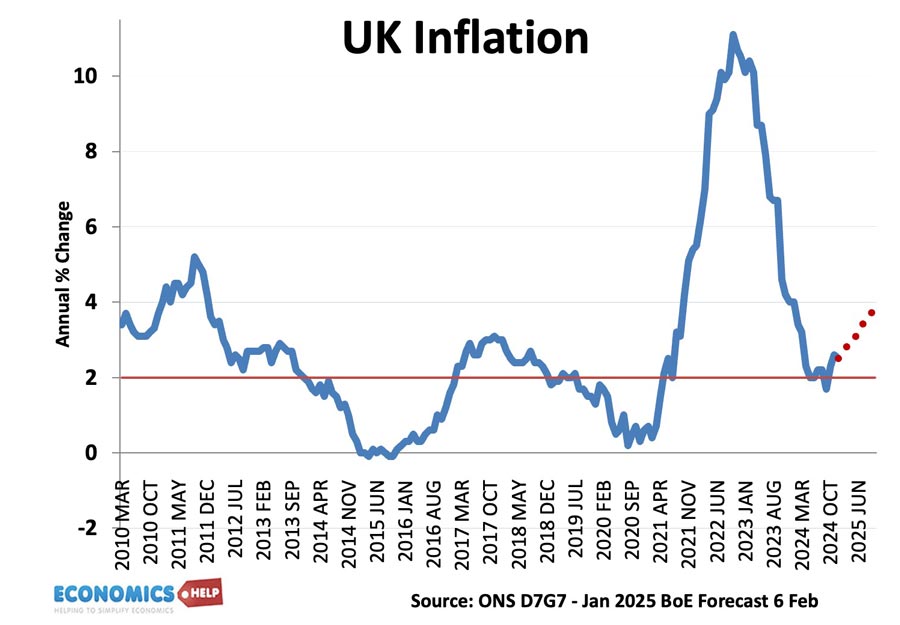

Inflation

On inflation, the headline rate has come down close to the target, but unfortunately, it is not forecast to stay there. Underlying core inflation is still higher and a further rise in gas prices are going to cause more inflation. And this is the worst kind of inflation – higher costs, but not related to rising wages. This will severely impact living standards, especially for lower income households who pay a higher share of income on energy. It will also come at a bad time for pensioners who lost winter fuel allowance. The one consolation is that it is nothing as bad as the 11% of 2022, and the Bank predict, or perhaps hope, it won’t have any second round effects. This means that when energy prices rise, firms often take the opportunity to increase other prices at the same time.

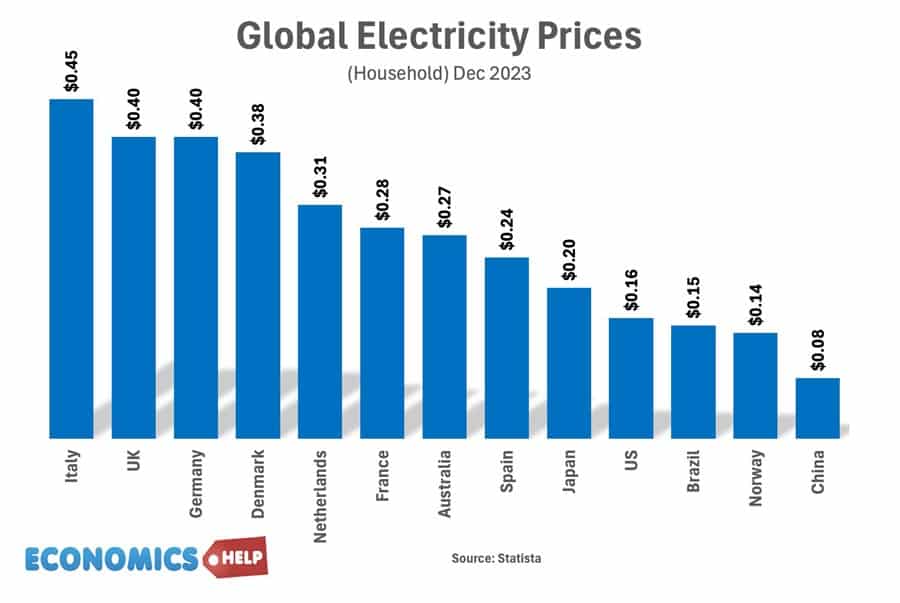

A big problem for the UK economy is our continued dependence on gas prices. We are vulnerable to a rise in prices because electricty is still determined essentially by market gas prices. Something is wrong with energy policy, given the UK has the highest electricity prices in Europe, and this has harmed an already weak industrial sector.

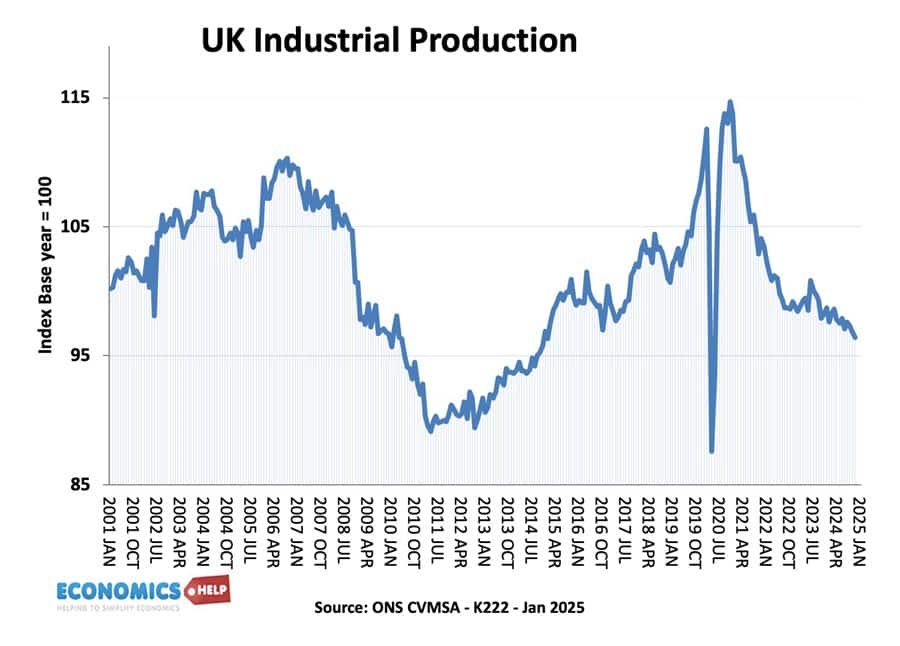

And if we look at UK industrial production it has seen a sharp fall since 2021 and is now lower, even than before the credit crisis, the deindustrialisation of the UK economy continues. Many of the problems of the UK economy are due to past decisions storing up problems. One of the key factors affecting growth and productivity is investment. But, on this metric, the UK has seen poor levels of investment. Total investment as a share of GDP is just 18% and this reflects both low private investment and low public sector investment. It is not helped by the fact that when the UK does invest, it tends to be more expensive and gives relatively poor returns.

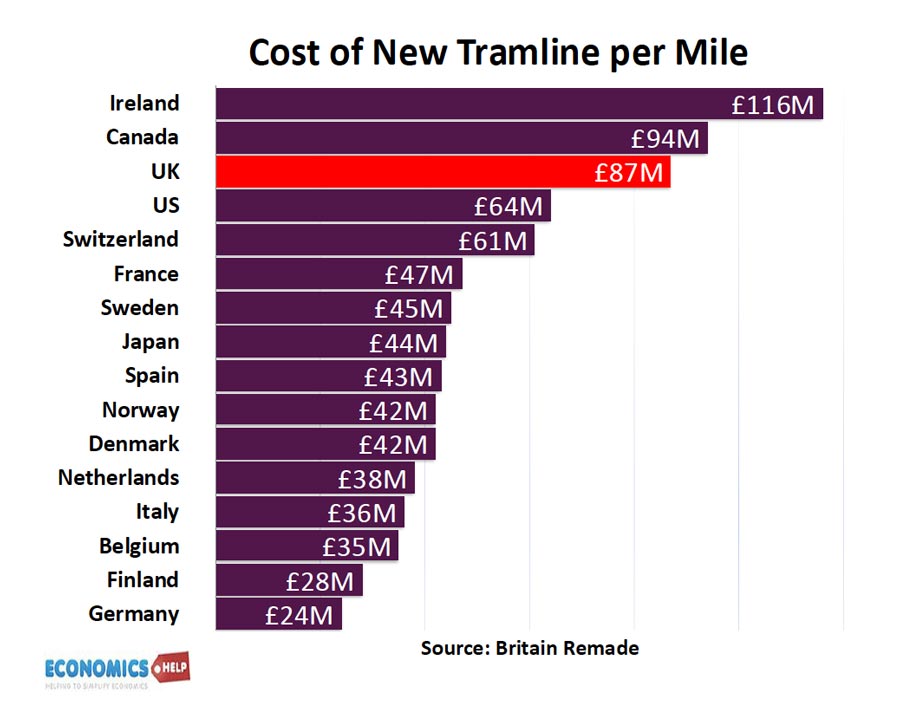

For example, the cost of building new tram lines is significantly higher in the UK than in comparable European countries such as Spain. The result is many northern cities and towns are hemmed in by poor transport infrastructure. The government have announced some increase in public investment, but at less than 2.5% of GDP its not particularly a game changer. They are hoping that approving projects like building reservoirs, nuclear power, Heathrow expansion and loosening planning legislation may help increase growth in the coming years. This is a positive step but will take time to come to fruition.

Poverty

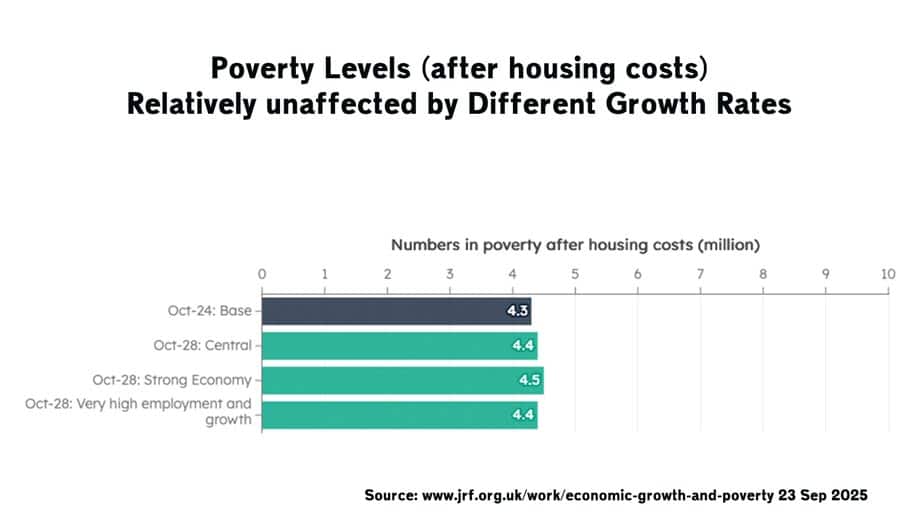

But, even if the government were to be successful and increases the rate of economic growth marginally, it may not do that much, if anything to move the dial on a sense of poor living standards. As the Joseph Rowntree report, even if we did magically get strong economic growth, it will do little to reduce the number of people living in poverty after housing costs. The reason for this is economic growth can further increase rents and house prices, yet fail to trickle down to the poorest. In the past decade economic growth has had only limited impact in increasing incomes of the poorest households. Benefits have frequently been increased at a slower rate than wages in recent years.

Housing Costs

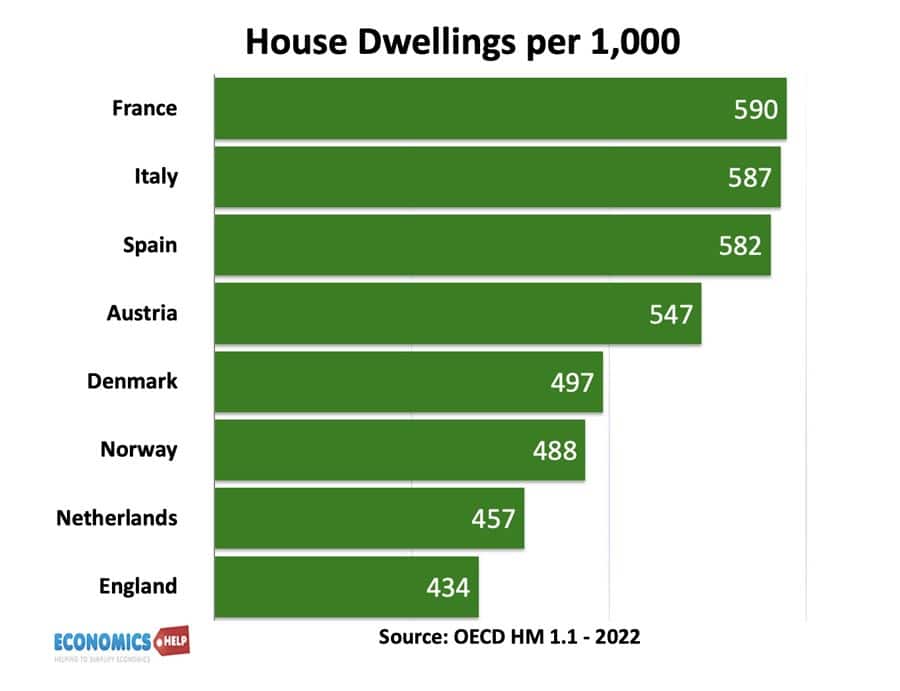

When economists talk about the economy, we tend to gravitate towards GDP, but for average households, it is more can we afford basic living costs, and so whatever happens to growth, the housing market is a continued weight on living standards. The UK has fewer housing stock per 1,000 people than European counterparts. Average house prices are eight times income, worse in higher growth areas like London. The rented market is also struggling. The rise in house prices has contributed to rising wealth inequality and this is forecast to get worse in the coming years. One reason house prices have continued to remain high despite cost of living crisis is that prices are being propped up by wealth and investors to keep housing of reach for many.

Minimum Wage

One bright spot for the economy is rise in minimum wage, which has gone a long way to increase incomes for those who are are the lowest paid. It is one reason for the decline in income inequality since 1999. But, combined with rise in national insurance contributions to take effect in April, business feel hemmed in by rising labour costs. Combined with threats of trade war and low confidence, hiring rates have been hit, and unemployment is forecast to rise. Ironically, the rise in national insurance further exaggerates tax distortions, with a higher cost for being employed rather than self-employed.

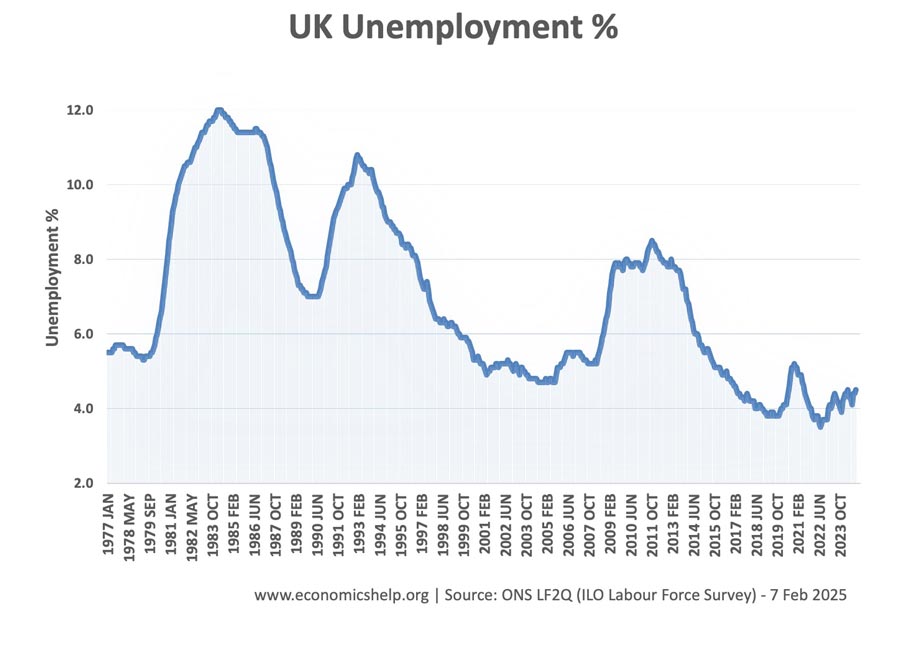

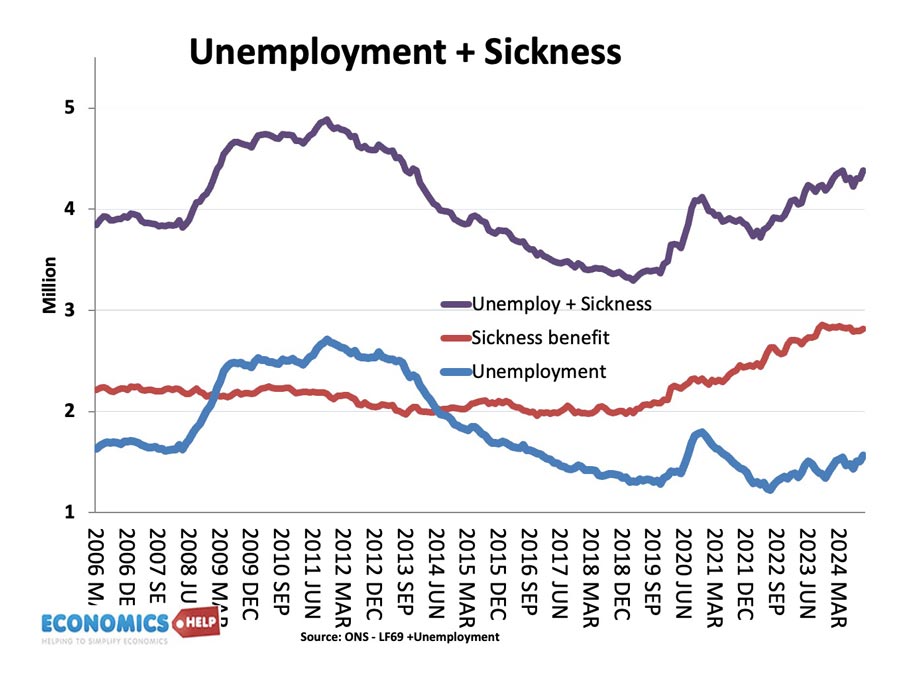

You could say a bright spot for the economy is the unemployment rate. The underlying unemployment rate has fallen considerably compared to the 1980s, and is now just 4.5%. However many such as Policy in Practise claim that the strict benefit regime has created a structural incentive for people out of work to move from unemployment to sickness benefit, where there is no work sanction, plus higher benefits. If we combine numbers of sickness benefits and unemployed, then this combined measure has increased by 1 million since 2018.

Amidst all the gloom of the UK economy, the government may take solace from the fact that Mr Trump seemed to suggest the UK may be in a better position to avoid tariffs than the rest of Europe. But, to be excited by a special Trump exemption on tariffs would be to miss the point. Trump’s tariff policy is very unpredictable, the only certainty is that growing trade tensions will harm growth for all countries, where trade is still important. In fact, the threat of a more unpredictable US, makes the UK look more isolated since it is now outside the EU. The Brexit trade deal is less than satisfactory and has hit UK goods exports, though services have done much better.

Two-Speed Economy

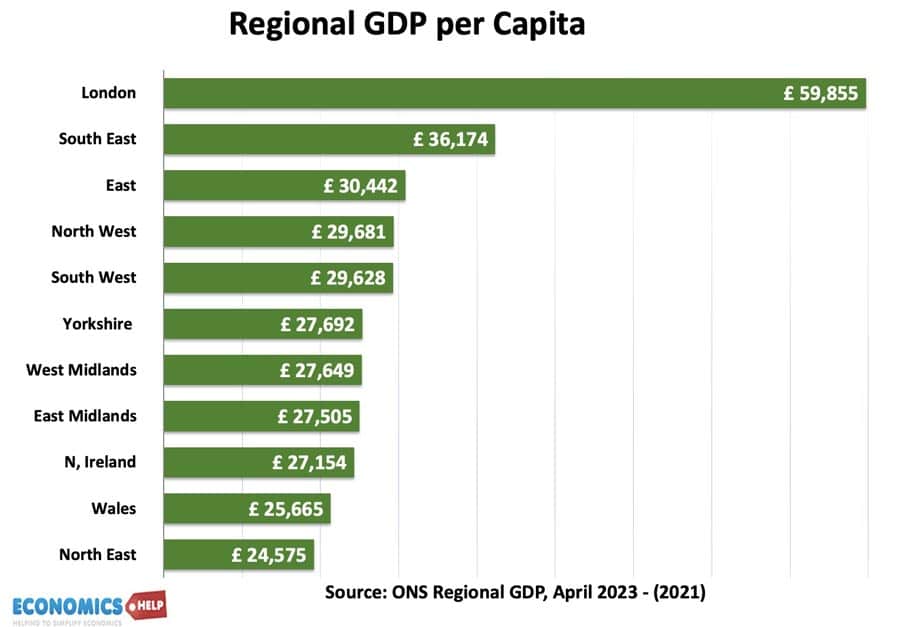

In fact, the UK’s reliance on the service sector, and especially finance continues to grow and one issue is that this tends to be focused around London. The UK is a two speed economy – London and the rest of the country. Outside London 42% of graduates fail to get a graduate job. For all the talk of levelling up, the economy struggles to devolve economic opportunities to areas outside London. London still attracts the bulk of investment. The result is large regional inequality. But, for those who live in London, many face rents as a high share of income, with average rents over £2,000 a month. Whilst the UK’s population has increased in recent decades, home building has not.

Long-Term Debt

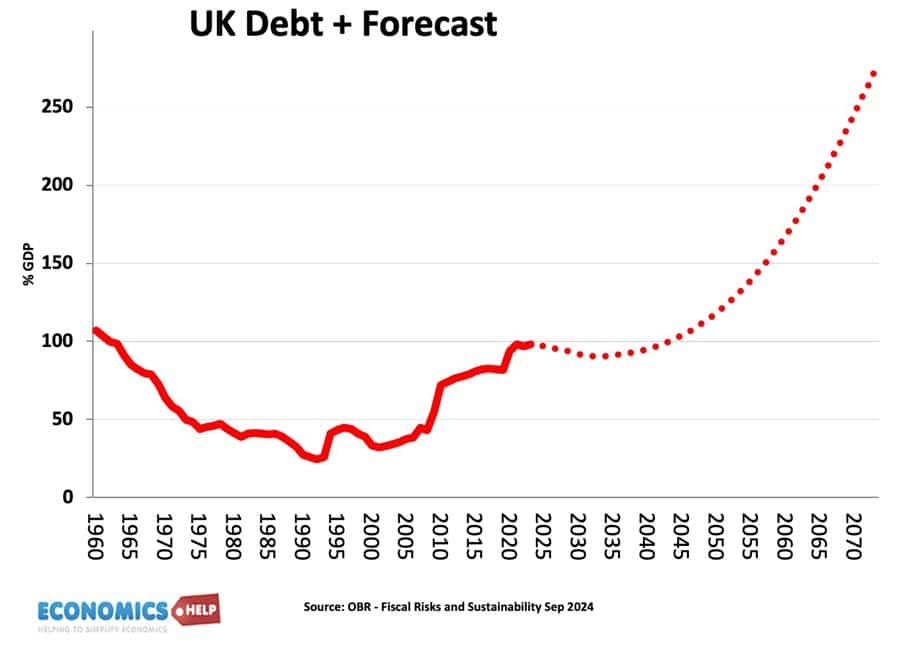

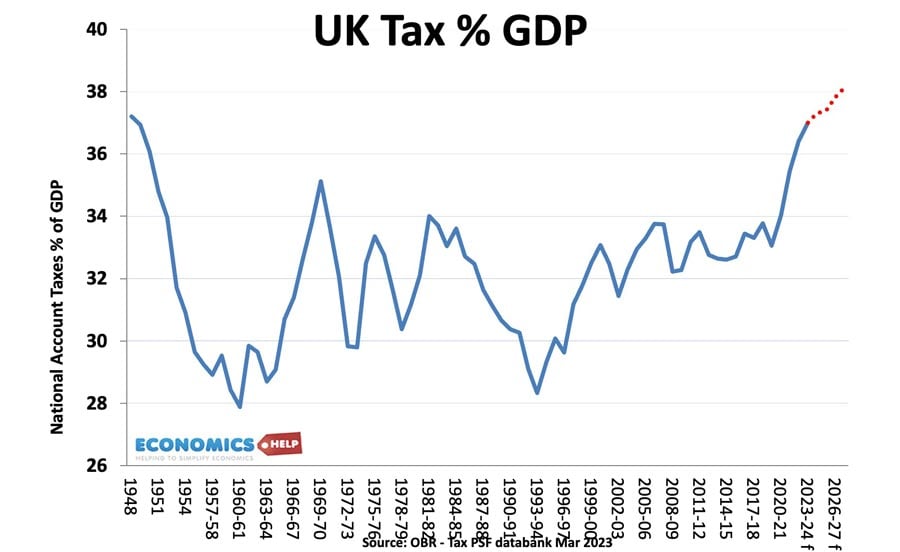

Another problem is that the government are running a budget which assumes growth will pick up, and if the dismal growth forecasts materialise, it could force further austerity measures, which of course, will only further worsen demand in the economy. The bigger long-term problem is that the government faces unwelcome demographic changes.Despite high migration, the UK is still an ageing society, the share of people over 65 will continue to grow in the coming years. This will make a tight fiscal situation worse. OBR forecasts suggest public sector debt is going to rise sharply without any major change to policy. One option is to further increase tax rates, to levels seen in Scandinavian countries.

But, taxes are already at a record share of GDP, and there is little appetite for higher taxes. Denmark and Scandinavia have higher taxes, but a sense public services give a good return. In the UK, the past 15 years have left many holes in public spending, with enforced austerity for many departments. This is a real fall in spending power, which has contributed to a build of problems from hospital waiting lists, to potholes and delays with the criminal justice system. Faced with growing social care bills, local authorities are facing bankruptcy. As a short-term solution, the government will allow council taxes to rise up to 25%

Positive look?

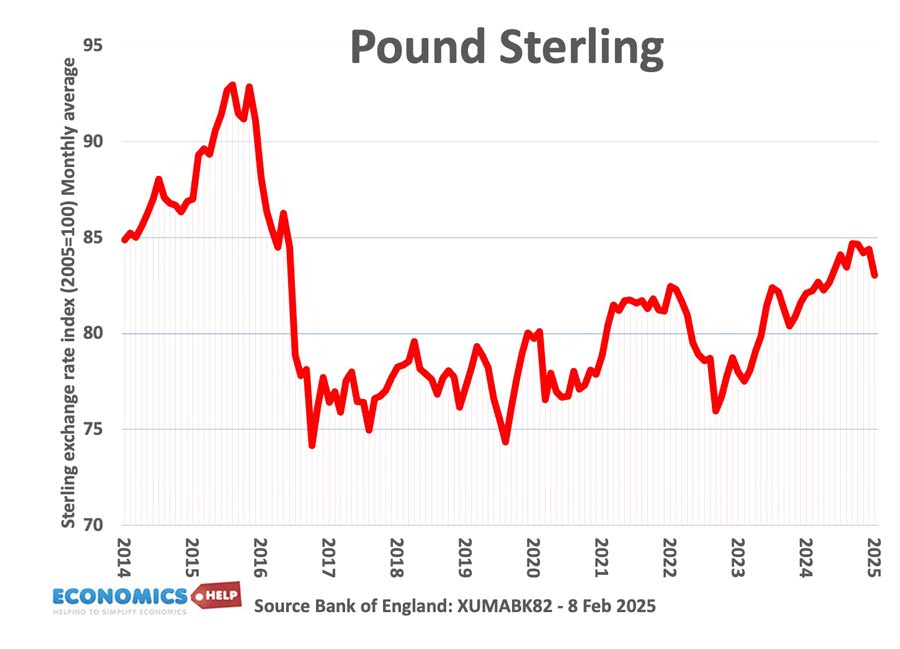

Given seeming unrelenting bad news, is there a danger of focusing too much on negativity. For example, there are many headlines about the weakness of the Pound, but it is 10% higher than the 2016 low. It’s hardly a crash in the Pound, though its relative strength is due to the relatively high interest rates.

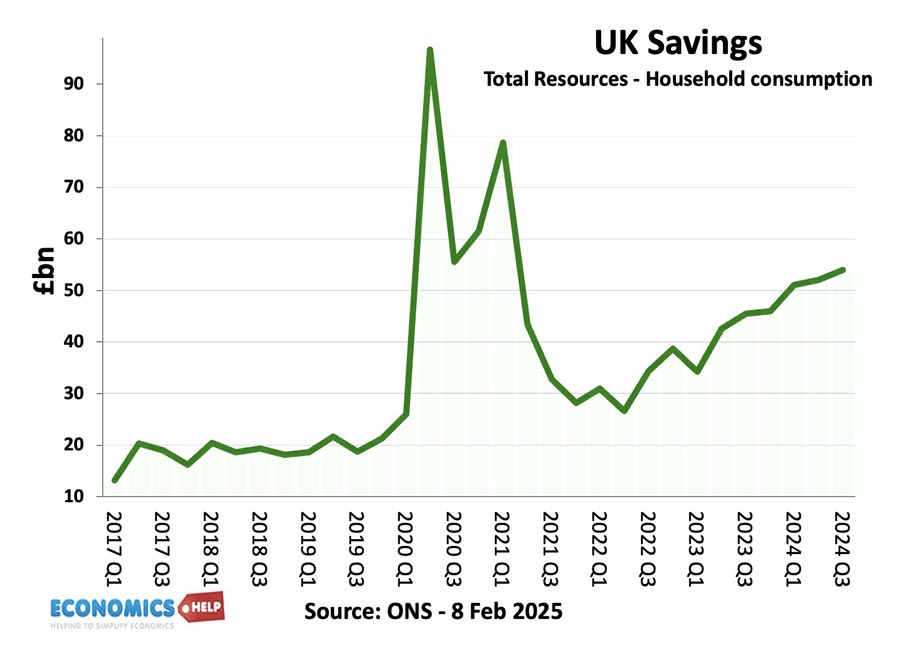

But, there are positive aspects to the economy. Firstly, low consumption and investment is at least partly due to low confidence. Saving rates have increased, which means in theory, there is room for higher spending and higher investment when more optimism returns. Arguably, the Bank of England should have done more to take advantage of this situation by cutting interest rates further.

Was it Great in the Past?

Secondly, when we say the economy is very bad, was there ever a golden period of the UK economy when everything was great? In the early 1980s, housing was cheap compared to income, but unemployment was over 3 million and consistently high. In the early 1990s, we experienced inflation of 9% and interest rates of 15%, which caused a massive period of home repossessions and deep recession. The 1960s were a period of strong economic growth and rising living standards, but their average living standards were relatively worse. In 1957, Harold McMillion told the nation “You’ve never had it so good.” But since then average GDP per capita has risen over 300%. It would be a mistake to think living standards are three times better, but they aren’t worse. Ironically one period of the highest level of real wage frowth was the 1970s, but it was also a time when UK inequality was at its lowest in history. But, the 1970s, also had very real economic problems. Inflation of over 20%, deep seated industrial disputes and a balance of payments crisis, which requried an IMF bailout. And if you went back to the 1930s, you would have very real economic hardship, no benefits, mass unemployment and poverty on a level not imaginable today. But, the bigger picture is that there is undeniable frustration. Things could be better and a sense of economic growth no longer leads to better living standards, and in both short and long-term there are reasons to be pessimistic that growth will return and lead to a meaningful increase in living standards we got used to in recent years. A big problem for UK is regional divide with London increasingly dominating the economy in a way you don’t see in other countries. This video looks at the London problem from both the perspective of the UK and ordinary Londoners.

Related

https://www.ft.com/content/8d3c8f8b-ea5b-46a9-b0d6-4f119081e506