Reader’s Question: Why Does Inflation Make it Easier for Governments to pay back the debt?

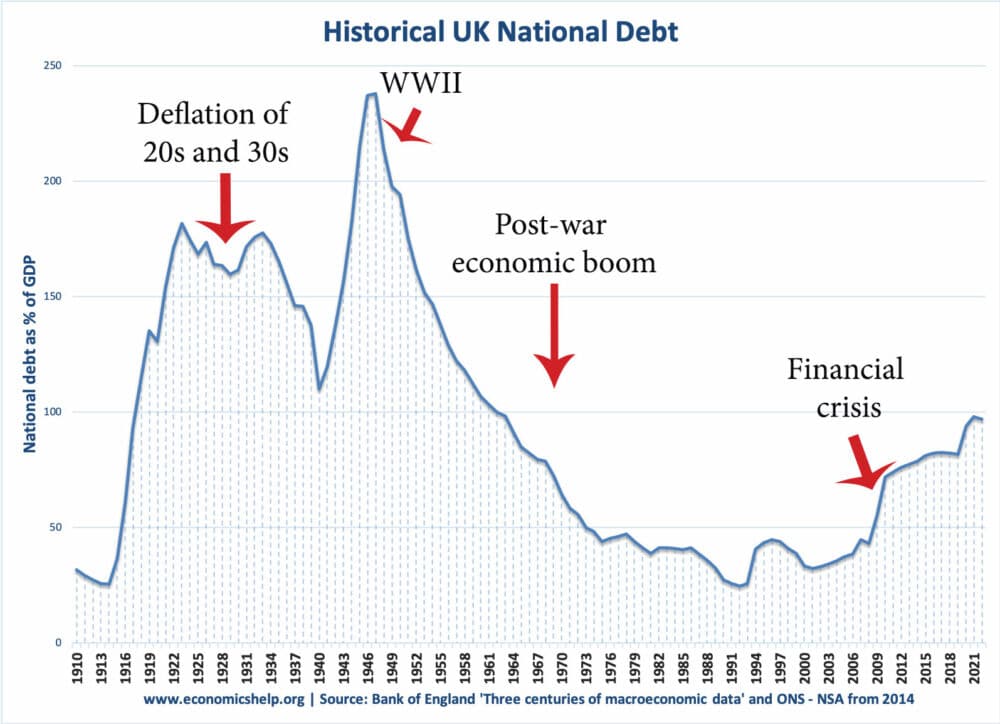

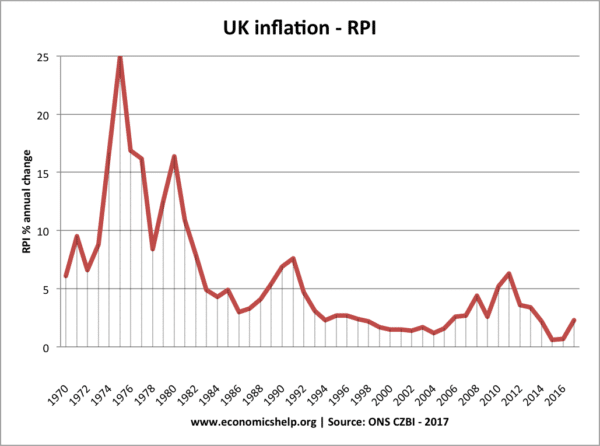

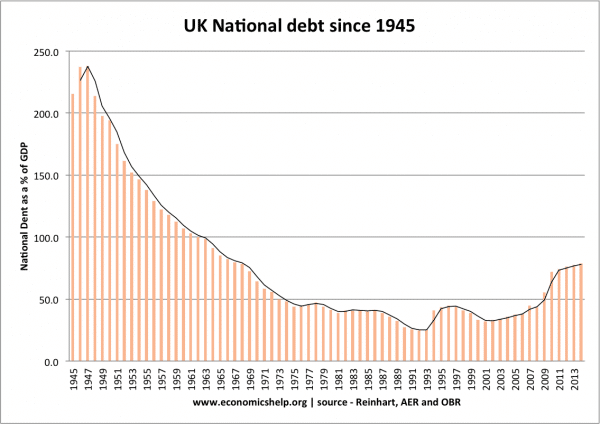

The big fall in national debt as % of GDP occurred during relatively high inflation periods of 50s, 60s, and 70s. The 1920s and 30s were a period of deflation and high debt.

There are a few reasons inflation makes it easier for a government to pay its debt, especially when inflation is higher than expected. In summary:

- Higher inflation increases nominal tax revenues (if prices are higher, the government will collect more VAT, workers pay more income tax)

- Higher inflation reduces the real value of debt, bondholders on fixed interest rates will see a fall in the real value of their bonds and it becomes easier for the government to pay back these bonds.

- Higher inflation can enable the government to freeze income tax thresholds so more workers pay higher tax rates – it becomes a way to increase tax revenues without increasing tax rates.

Why inflation can benefit the government at the expense of bondholders

- Let’s assume an economy has 0% inflation, and people expect inflation to remain at 0%.

- Then let us assume the government needs to borrow £2bn by selling 30-year bonds worth £1,000 to the private sector. To attract people to buy bonds, the government may offer an interest rate of 2% a year.

- The government will then have to pay back the full amount of the bonds £1,000, plus the annual interest payments on these bonds (£20 a year at 2%).

- The investors who buy the bonds will make a profit. The bond yield (2%) is above the inflation rate. They get back their bonds plus the interest.

- However, suppose, unexpectedly there was inflation of 10%. This reduces the value of money. As prices go up because of inflation, £1,000 would buy a lower quantity of goods and services.

- Because of inflation, the government would get more tax revenue as wages and prices increase (e.g. if prices go up 10%, the government’s VAT receipts will increase 10%)Therefore, inflation helps government automatically get more tax revenue.

- However, bondholders lose out. The government still only have to pay back £1,000. But, inflation has reduced the value of that £1,000 bond (real value is now £900.) The inflation rate (10%) is higher than the interest rate (2%) on the bond, so they are losing the real value of their savings.

- Inflation means that repaying bondholders requires a smaller % of the government’s total tax revenue – so it is easier for government to pay back the original debt they borrowed.

The Government (borrower) is better off, bondholders (savers) are worse off as a result of inflation.

Evaluation (index-linked bonds)

Because of this risk, some bondholders will buy index-linked bonds. This means that if inflation increases, the maturity value and interest rate on the bond automatically increases in line with inflation – to protect the real value of the bond. In this case, the government doesn’t benefit from inflation because it ends up paying higher interest payments and it can’t devalue the debt through inflation.

Inflation and benefits

In 2022, the UK has forecast inflation to peak at 6.2%, which will lead to a sharp rise in nominal tax receipts. However, the government has increased benefits and public sector pay at a lower rate of inflation. In April 2022 inflation-linked benefits and tax credits will rise by 3.1 per cent – this 3.1% was decided from the (CPI) inflation rate back in September 2021.

Therefore, public sector workers and benefit recipients will see a real fall in income – their benefits will rise 3.1%, but inflation could be as high as 6.2%. In this case, the government budget position will improve by raising benefits at a slower rate than inflation.

Debt is only improved by the conscious decision to raise benefits and wages at a lower rate than inflation.

Inflation and bracket creep

Another way government finances can benefit from inflation is to keep the income tax threshold fixed. For example, the basic rate of income tax (20%) starts at £12,501. There is a 40% tax rate at £50,000 and 50% tax rate at £150,000. Inflation will mean nominal wages increase and more workers will start to pay income tax at higher rates. Therefore, the government effectively increase average tax rates – even though it appears the tax rate stays the same.

Long Term Implications of inflation on bonds

If people buy bonds expecting low inflation, but then lose their real value of savings because of high inflation, they will become reluctant to buy bonds because they know inflation can reduce the value of bondholders’ savings.

If bondholders fear the government may cause inflation, then they will want higher bond yields to compensate for the risk of losing money through inflation. Therefore the prospect of high inflation can make it more difficult for the government to borrow.

Note: bondholders may not expect zero inflation, what damages bondholders is unexpected inflation.

Example Post War Britain

In the 1930s, inflation was very low. This is one reason why people were willing to buy UK government bonds at low-interest rates (in the 1950s, the national debt increased to over 230% of GDP). In the post-war period, the debt burden was to some extent reduced by the effects of inflation which made it easier for government to meet its repayments.

In the 1970s, unexpected inflation (from oil price shock) helped to reduce the government’s debt burden in various countries such as US.

The fall in UK national debt as a % of GDP in the post-war period was partly accelerated by inflation – reducing the real burden of debt. Though debt also fell due to a prolonged period of economic growth and rising tax revenues.

Economic Growth and Government Debt

Another issue is that if the government reflate the economy (e.g. pursue quantitative easing) this may also stimulate economic activity as well as inflation. Higher GDP is a key factor in helping government gain more tax revenues to pay back debt.

Bondholders may be nervous of an economy that is predicted to have deflation and negative economic growth. Although the real value bonds can increase with deflation, they may fear the economy is stagnating too much and so the government will struggle to meet its debt.

Further reading

1. Why will wages increase with inflation?

2. “If prices increase, VAT receipts will also increase”. This is based on the assumption that the demand remains the same. However, with increase in prices, demand will fall. Am i right?

Because inflation is essentially new money in the economy the prices goes up, but companies can payhigher salaries (and employees need more money to buy the same stuff so they demand it). Nominal prices goes up, but people can still afford the same. The difference is that government gets more taxes and can easily repai debts (and at the same time people with debts can more easily repay them with higher salaries and therefore afford to buy more).

Don’t forget to mention that, although governments can pay back debt more easily, the value of all savings in the country is devaluated by the amount of inflation.

If there is 10% inflation and your grandma has 1000£ in the bank, it is now able to purchase 900£ worth of goods. She essentially lost some of her savings in the process.

Debtors in general (not only governments) are better off since the value of the nominal debt they contracted just went down 10%.

And when have you ever seen companies raise wages based solely on inflation or interest rates? For myself, never. 50 years worth of never. Prices go up. Government receipts go down because the economy is supressed by inflationary pressures. People do not buy more, tax receipts go down, money loses its value, and the end result is the slowing of everything due to rising costs and devaluation of the money used. This is a load of hooey.

Exactly, sb. I don’t think any of these assumptions that are put into the models are realistic. People may demand more wages from their employers, but with costs going up in general [overheads, utilities etc.], I don’t think the employers are in much of a position [especially smaller ones] to oblige.

And if interest rates continue to rise, then mortgage payments/loans become dearer, and you have possible stagflationery effects. As you note, people tend to buy less in such a scenario, they don’t just remain at the same level of consumption, so the economy [as a whole] should therefore contract.

I get that debt becomes ‘cheaper’ because the nominal value was set at a specific time, and that value has decreased with inflation. But I cannot clearly see this argument of why wages should go up during inflationary times, when employers themselves are having difficulties and being squeezed.

Also you need to see the timing of debt, since as mentioned above, if you have an interest rate hike then spreading that across the economy means that payments on the principal have actually risen. So it depends.

Is the cost of debt influenced by the previous inflation rate (year t-1) or by inflation rate today (year t) or inflation rate in the coming year (t+1)?

cost of the debt is influenced by the timing of the debt, if it was at t-1, then cost of nominal debt will apply. if the inflation rate is expected to increase in t+1 then the cost of debt/capital will likewise increase the real cost of debt through the new inflation rate in the t+1 period.

generally, higher the inflation rate, the cheaper the debt,as debt/1+r (nominal rate inclusive of inflation rate) will bring cost debt, hence benfecial for debtors.

if inflation is 10%, and remains so, for say 5 years, then if the bond is a 30 year bond, what then?

Thank you for your very interesting and well written article.

As a life long saver l can only see the dire consequences from what appears to be uncontrolled inflation. Currently this is running at around 8% and rising (who knows where this is going as we appear to be going from one crisis to another). Just for reference the uk tries to maintain an inflation rate of around 2%. The base rate is currently 0.75% (April 2022) and the Bank of England appears unable or unwilling to raise this more than around 1% (the base rate being the main tool used to control inflation) . From this l can only assume the BOE and the government is going to let the market decide on how far inflation goes. On a personal level I have a number of ns&i bonds paying around 0.5% which are due to mature in 2024. Just for reference l am just a normal working guy and saved a bit to supplement my state pension assuming this comes to fruition.

I know l am going to take a massive hit then again l guess many other people are in a similar boat. As with any crisis l realise their will be winners and losers. Unfortunately it always appear that it goes mainly one way and the inequality gets even greater.

Hopefully things aren’t as bleak as l think they’ll be.

I would be really interested to hear what others think?

I’d like to

It seems clear that the inflation hike is being driven by the government as they are the key beneficiary. They could easily slash fuel duty whilst the Ukraine / Russia issue is in play and inflation would go away but they choose not to. The government is using inflation to recoup COVID debt.

Increasing interest rates just punishes the working class. It won’t be long before people start realising what the government is doing. Don’t let MPs set interest rates – have we learnt nothing from history. The Bank of England should be calling on MPs to reduce inflation by reducing the cost of fuel.

Just a really minor technical comment. If inflation is now 10%, the index rises from 100 to 110. Should the nominal £1,000 now be worth £909 in real terms today? (£1,000/1.10) and not £900?

Yes. I was doing a more broad explanation of 10%

The debt reducing aspect of inflation has been totally(deliberately?) ignored in the current cost of living crisis. It is bound to be introduced by economists sooner rather than later. IFS (Paul Johnson), where are you?