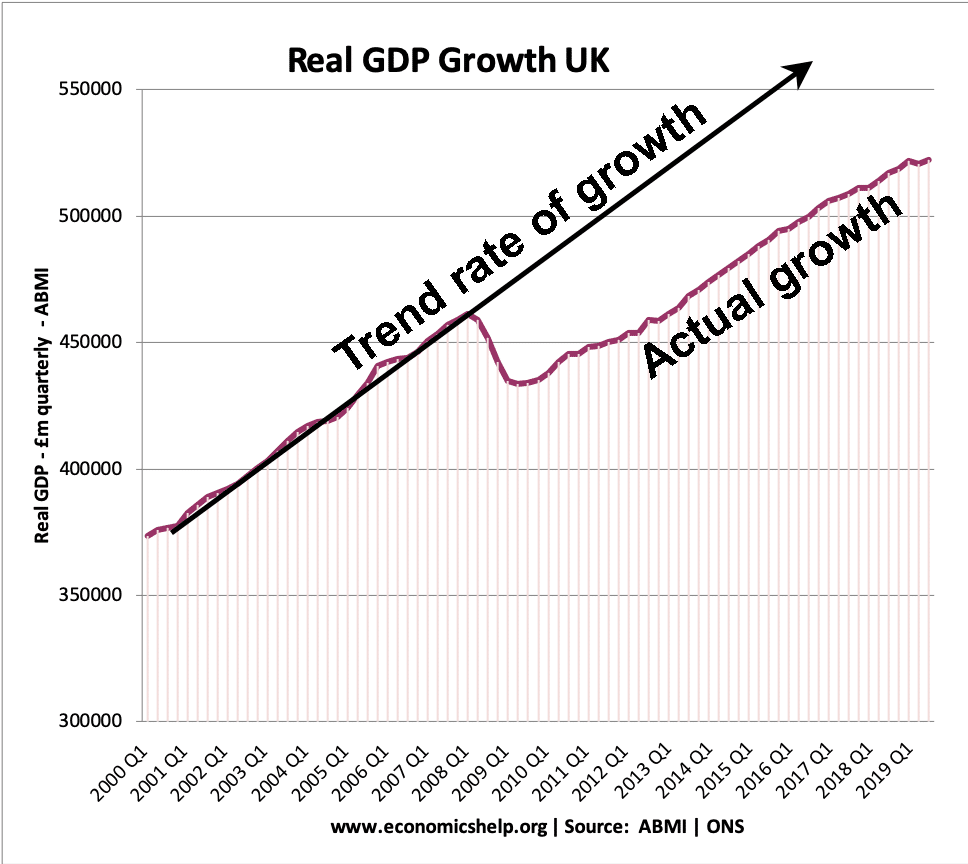

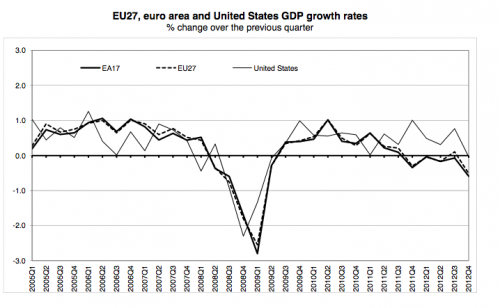

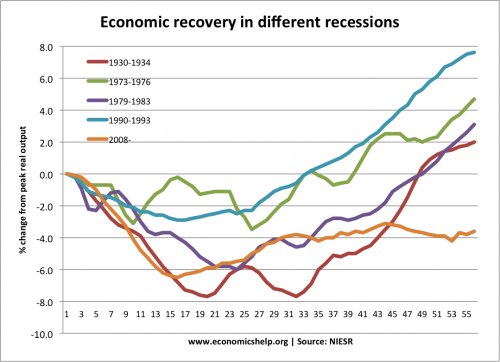

The post 2008 recession has seen the longest decline in real GDP on record. 55 months after the peak output of 2008, the UK economy is still 4% below it’s peak. By contrast, in the same time frame during the early 1930s, the economy had recovered to be more than 2% higher than the 1930 peak.

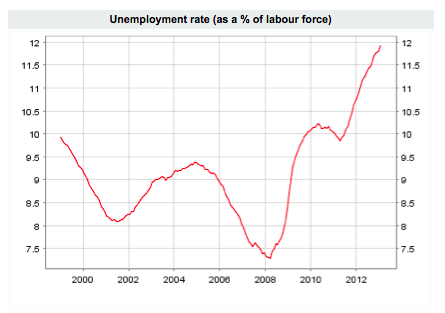

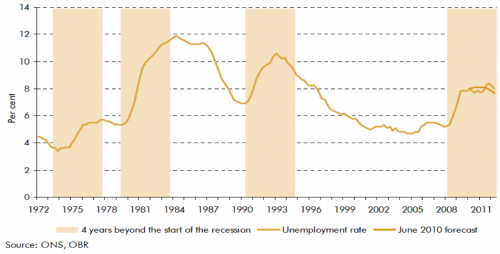

The 2008-13 recession is longer lasting than even the great depression. Yet, curiously the 2008 recession has seen one of the least damaging rises in unemployment.

Firstly, a look at the percentage change in real GDP since peak output (just before when the recession started)

For the first 15 months, the decline in real GDP is comparable to the great depression of the 1930s. The great depression shows a bigger fall in GDP (-8.0%) from peak. But, after 33 months, the economy recovered quite strongly in the early 1930s. The experience in 2008-13 shows a rare continued stagnation.

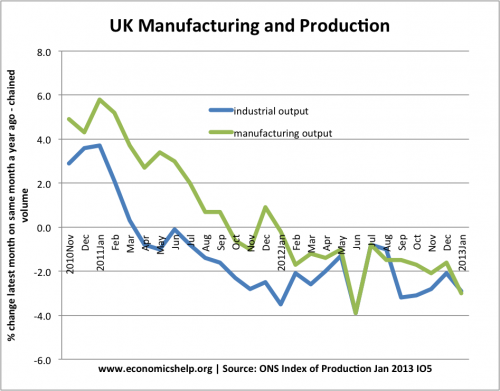

Unemployment in different recessions

This shows that the rise in unemployment has been relatively muted during the 2008 recession. In 2008-12, There has been a surprising growth in private sector employment – despite weak private sector investment and spending.

See: reasons to explain the UK unemployment mystery

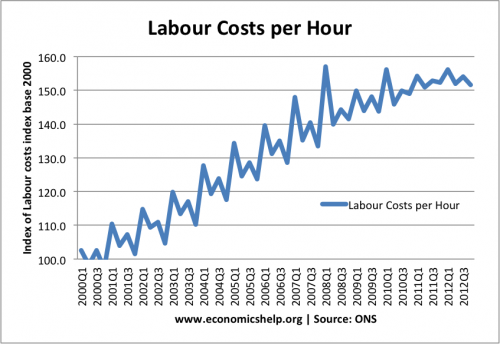

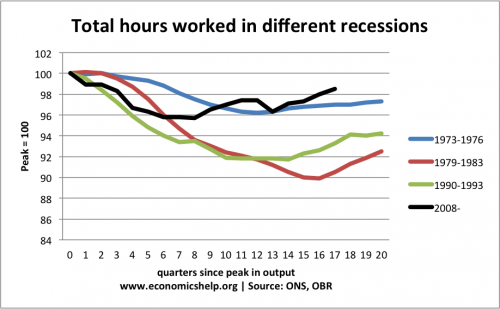

Hours worked in different recessions

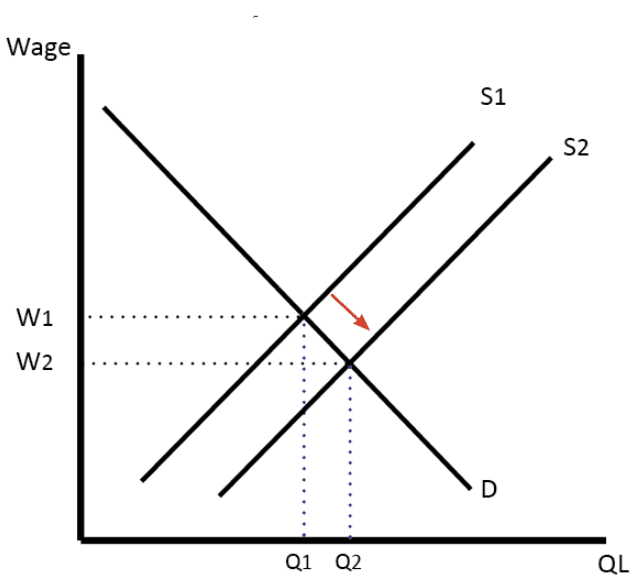

This shows that 17 quarters after the peak GDP, employment levels have fared better in 2008 than in other recessions. A rising population may be one factor, but the muted rise in unemployment suggests that the labour market in 2008-13 has proved more resilient and more flexible than many might have expected.