The OBR has recently made a prediction that UK national debt could soar from the current 100% of GDP to 320% within 50 years. This bleak assessment is made with regard to factors such as demographic pressures, requiring higher spending on welfare and health care, plus recent geopolitical events and rising energy prices. In 2009, national debt was just 35% of GDP, so what explains the sharp rise in debt, and will this trend continue?

Video version

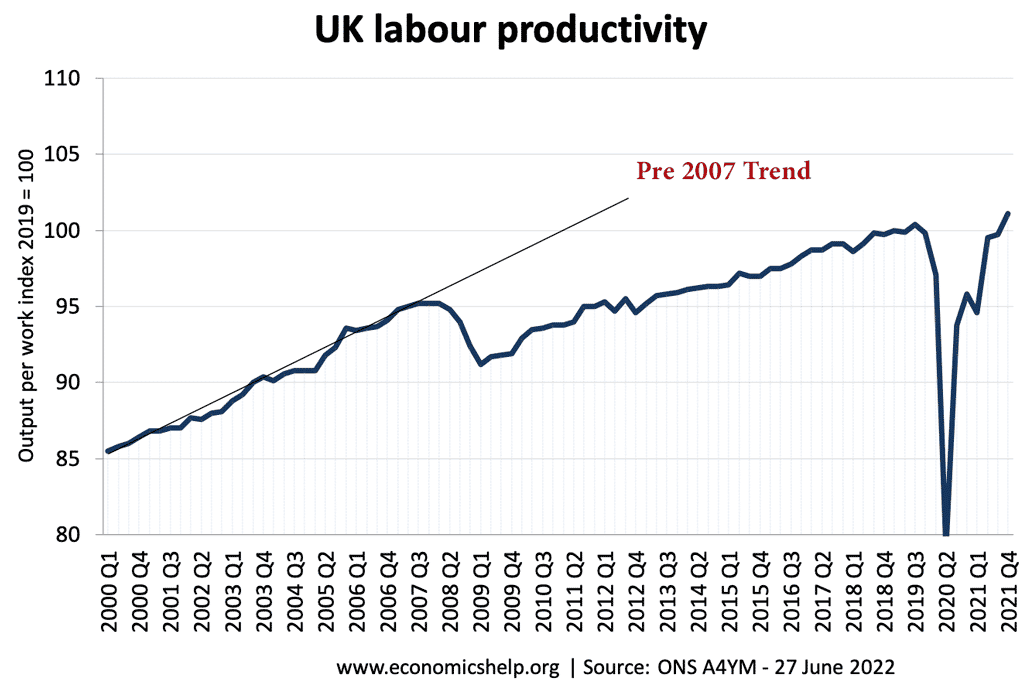

The most worrying trend of the UK economy is stagnant productivity, which has meant the growth rate has slowed down sharply since the post-war boom period. With lower growth, the government is not getting the same boost to tax revenues, that it used to enjoy. The reduction in debt during the post-war boom was not because of spending cuts and fiscal austerity, it was because we enjoyed a long period of economic expansion which enabled higher tax receipts – without raising tax rates. The very real concern is that the recent poor growth performance is a sign of secular stagnation and permanently lower growth rates.

In addition to falling productivity, the impact of Brexit is increasingly being felt with a fall in potential export growth with the EU. The OBR calculated the cost of Brexit to the nation’s finances to be in the region of £40bn. (OBR)

At the same time, many traditional tax sources are coming under pressure. In 2021/23 fuel duty revenues raised £26 billion. But a switch to electric cars and a decarbonising economy will see these tax revenues fall away quite sharply. Other revenue sources, such as corporation tax, alcohol and tobacco taxes are also falling as a share of total tax revenue, placing more strain on the politically unpopular VAT, and income taxes. The surge in energy prices which could see prices double over the winter will also leave the government wishing to offer some fiscal support in the form of tax cuts or grants.

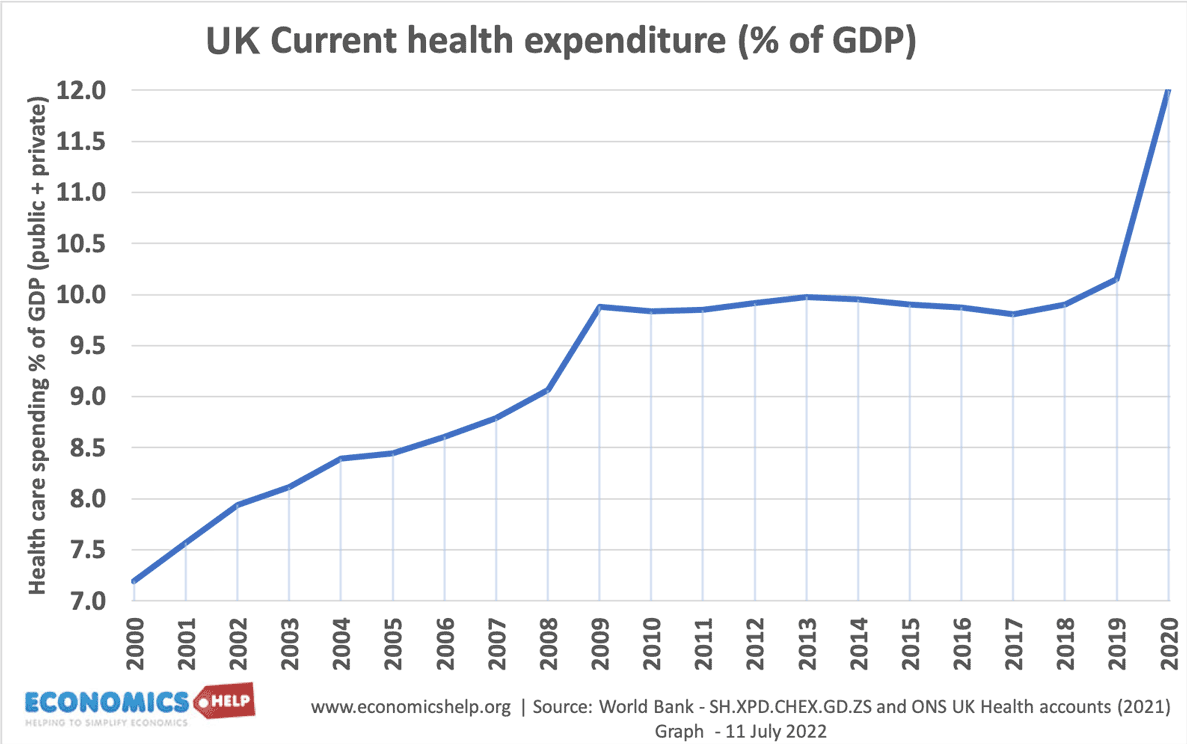

Perhaps more concerning than falling tax revenues, is the big increase in demand for public spending. Demand for Health care spending, like many western economies, is growing faster than inflation and economic growth, taking an ever-increasing share of national income. This is due to both more medical treatments (often expensive) and an ageing population, which requires more health care, than a younger population. Despite inflation-busting increases in health spending, the UK is still seeing record waiting lists and a national health service which is visibly under strain. All this was worsened by the recent Covid pandemic and the growth of long covid.

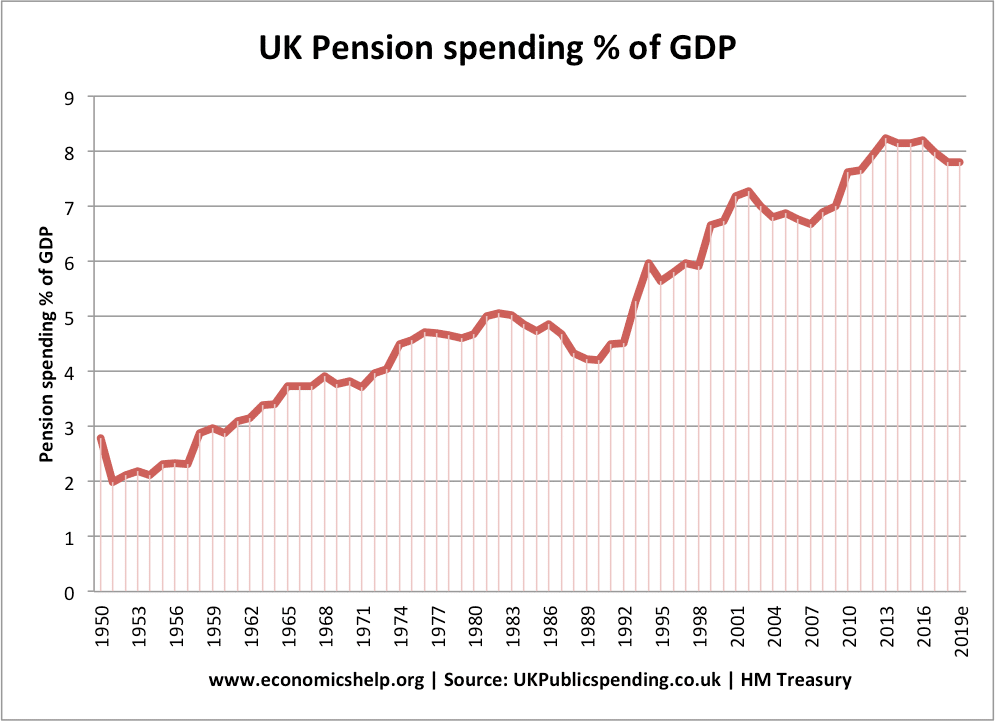

An ageing population also places more demand on pension spending. Pensioners are a strong political force (they are more likely to vote) so the triple lock mechanism for pensioners combined with more old people, is seeing big growth in spending.

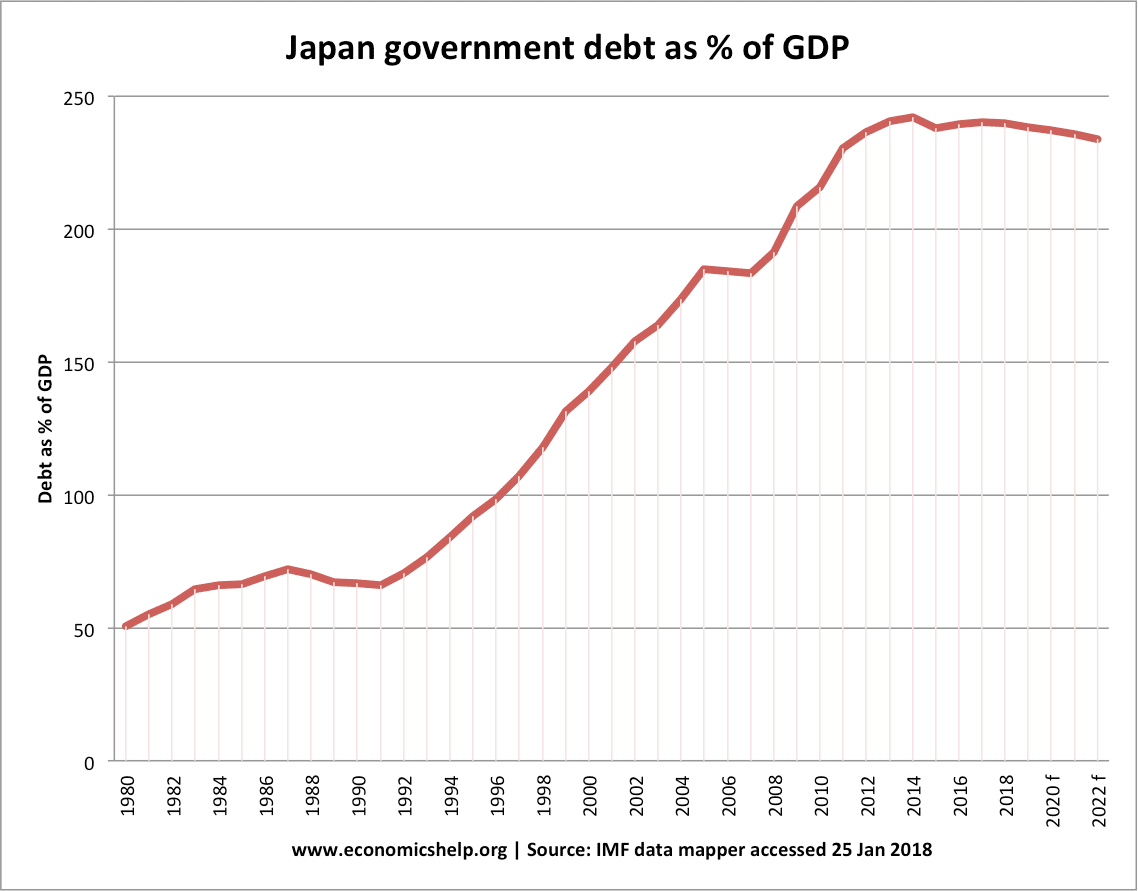

To get an idea of the pressures the UK face, it is worth looking at Japanese debt. Japan underwent an ageing population earlier than Europe, and from the mid-1980s, saw a fall in productivity growth and the post-war miracle was replaced by anaemic growth and deflationary pressures. Japan’s national debt soared to 240% of GDP, largely due to similar demographic pressures, the western world now faces. Interestingly the debt remained quite manageable because with the high level of domestic savings, there was strong demand for buying bonds and interest rates have remained very low in Japan.

The OBR also raise the recent geopolitical events as a sign that defence spending may rise as quite a few recent Tory leadership hopefuls have promised. In the post-war period, higher health spending was largely accommodated by cuts to defence spending, but if this is reversed, it will cause more budgetary pressures.

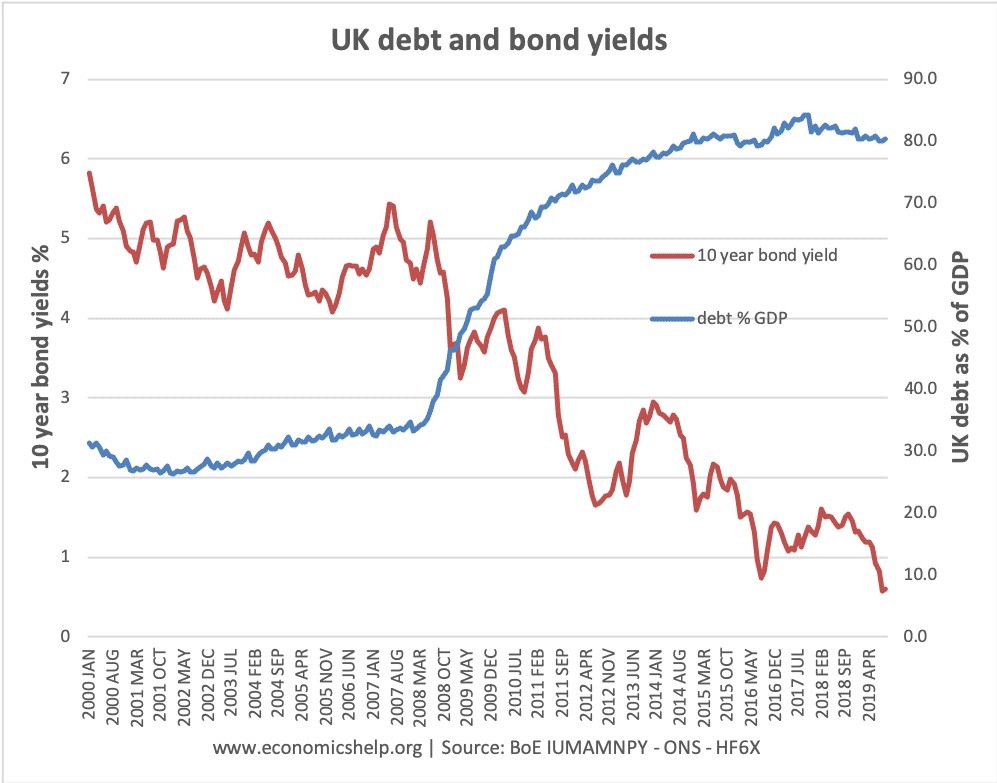

It is not possible to mention national debt without the politics of the issue. The OBR was set up in 2010 by the new Conservative/Lib Dem government who won the 2010 election largely on a platform of fiscal responsibility, after the high budget deficits of the 2009/10 years under Labour. Fears over debt dominated the 2010 election and it led to a period of austerity as spending was cut in the proceeding years. Over 12 years later, fiscal austerity has waned in importance, to be replaced with a more populist period of promising higher spending and tax cuts. Especially during the Covid Pandemic generous government support to individuals and businesses proved quite popular. Also, the fears of 2010 that higher debt would be unsustainable and lead to higher interest rates now appear rather quaint. (It was never good economics – see article from 2012 – why is austerity politically popular?) Debt rose, but interest rates fell, highlighting that higher government borrowing is quite manageable in a period of low-interest rates and low growth.

The point is that tackling the projection of national debt will prove politically very difficult. We could replace fuel duty with electronic road pricing, but the last time it was suggested under the last Labour government, it was soon withdrawn after public pressure. The main problem is that in recent years, the tax burden has increased very significantly, but we don’t have much to show for it. Whilst taxes are higher, there is a sense of underspending on public services, public sector pay and public sector investment. Any future government will face huge pressures to keep public spending rising, whilst at the same time, trying to promise tax cuts.

The OBR prediction is very much dependent on so many factors. We could see important technological breakthroughs (e.g. Nuclear fission, more renewables) which lead to cheap energy and not relying on imports. If we get a return to post-war growth levels averaging 2.5%, it would make it much easier for the government to start reducing debt to GDP. Also, demographic pressures have slightly been reduced by a falling birth rate (fewer people in schools) and a decline in life expectancy (fewer pensions and health care)

Further reading

Interesting video, my debts went up whilst I was watching because the interest rate hikes were not keeping up with income.