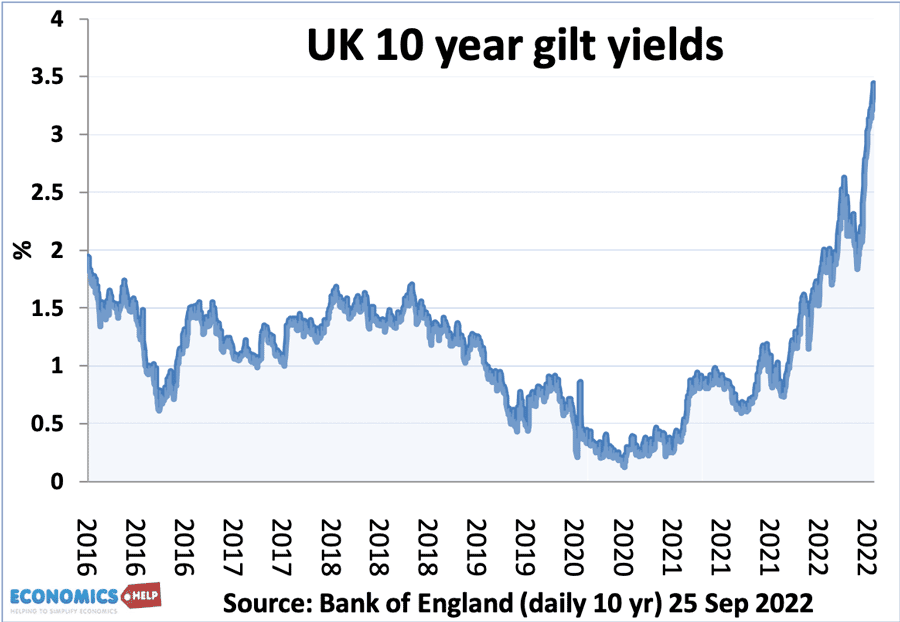

As the chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng was announcing his radical budget of energy bailout, and tax cuts for corporations and high-income earners, the markets took a dim view. Sterling fell and bond yields on government debt rose as investors sold UK bonds in response to the deteriorating outlook.

Uniquely for such a large change of fiscal policy, the government didn’t want the OBR publishing an independent forecast for the outcome of public finances, presumably because they will be so dire.

Former US Treasury secretary Lawrence Summers slammed the budget, arguing the Pound will likely fall below parity to the dollar.

“It makes me very sorry to say, but I think the U.K. is behaving a bit like an emerging market turning itself into a submerging market,” (Market Watch)

Usually, when governments announce big plans to increase borrowing, it leads to a rise in the value of the currency. This is because, higher borrowing, leads to higher interest rates, making the currency more attractive. However, the UK is experiencing the unwelcome combination of rising interest rates and a falling currency. This is indicative that markets are fearful of future UK economic growth, higher inflation and plans to deal with rising debt.

Prospects for growth remain very weak

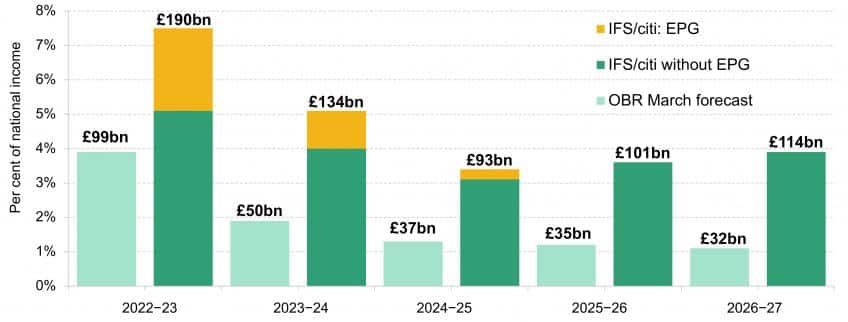

Combining the energy bailout with permanent tax cuts will drive up borrowing by £411 billion in the coming years, but the nature of the borrowing will do little to increase economic growth.

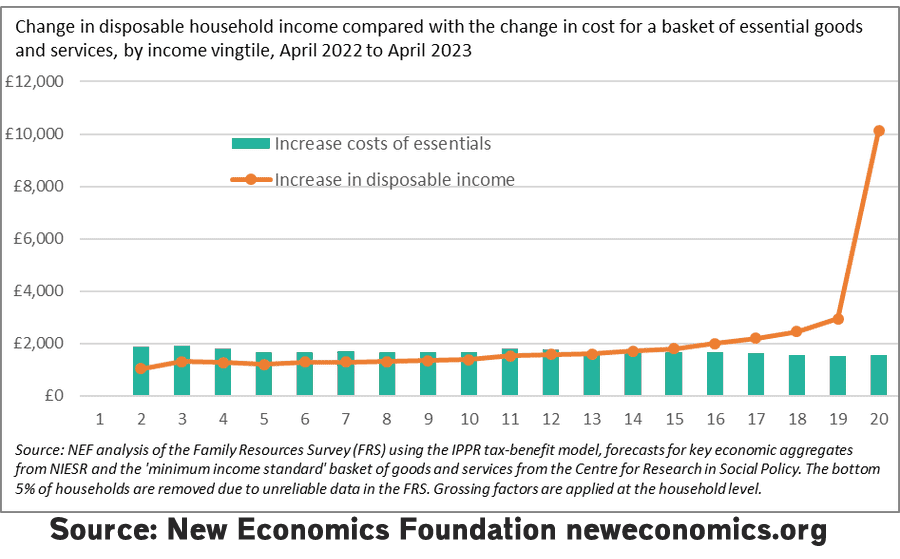

This shows that for low (and middle) income groups the rising cost of essentials is greater than the increase in disposable income from budget. It is only the top 20% of income earners which are seeing a rise in income greater than costs.

Therefore, the majority of households will not feel better off and continue to cut back spending.

By focusing tax cuts on high-income earners, the fiscal expansion is largely wasted. A lot of the tax cut will be saved.

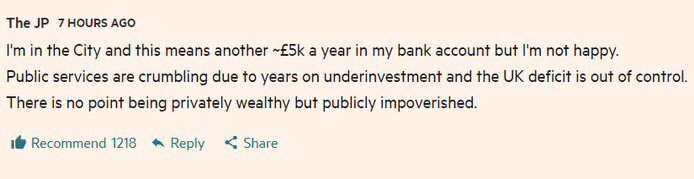

This comment is interesting as it highlights a perspective on personal wealth and public wealth. It is also interesting ‘An extra £5k in bank account’. That is also a key point, higher tax cuts for high-income earners are largely saved. (especially if you are pessimistic about the future)

Also, the expansionary effect of tax cuts will to a large extent be offset by higher interest rates. Markets are now pricing in interest rates of 5.5% or more – which will reduce demand, especially for the younger workers with large mortgages.

Some people talk about a ‘barber boom’ and an inflationary rise in demand, but despite the large rise in borrowing, the impact on demand may prove quite limited because there are so many conflicting pressures in the economy. As some observers have mentioned, it is like the UK is driving a car with one foot on the (fiscal) accelerator and one foot on the (monetary) brake.

Impact on long-term growth

More seriously is the issue of whether large tax cuts will cause a boost in economic growth and help make the borrowing more sustainable. Markets and most economists do not believe this to be the case. There is very limited productivity rises from cutting tax for high earners. There is no strong link between cutting corporation tax and prolonged higher levels of investment. (see: effect of tax cuts)

The real challenge to UK stagnant growth is poor productivity, low investment, demographic factors and low global growth and this cannot easily be solved by tax cuts (or indeed any government policy).

A better policy would have been to use fiscal expansion on investing in green energy, insulating home and improving basic infrastructure. This would at least have the benefit of helping to reduce future energy crisis and reduce dependence on foreign imports of energy.

Borrowing to Rise

Source IFS – Mini Budget response

As a result of the budget, borrowing for 2022/23 will now be £190bn rather than £99bn (and it could be worse if government revise spending upwards due to high inflation).

Importantly, even when the Energy Price Guarantee (EPF) expires, borrowing will be significantly higher because of tax cuts, rising interest payments. Also, there is no guarantee the energy price guarantee will not be more expensive if gas prices remain high.

So will there be a debt crisis?

Markets dislike the mini-budget because it is a serious deterioration of the UK’s position, big increases in borrowing, but no long-term benefit and real concerns about the future of inflation. Markets are currently expecting debt to grow on an unsustainable path, which will lead to the necessity of politically unpopular future tax rises, and spending cuts. However, that doesn’t mean (at least in foreseeable future) the UK will face a debt crisis as we see in emerging economies, such as Argentina. This is for a number of reasons.

1. Lender of Last Resort. The Bank of England acts as a lender of last resort to the government. If the gov’t could sell bonds, the Bank of England would buy, creating money if necessary. This helps to reduce liquidity issues, which plagued Euro countries in 2012.

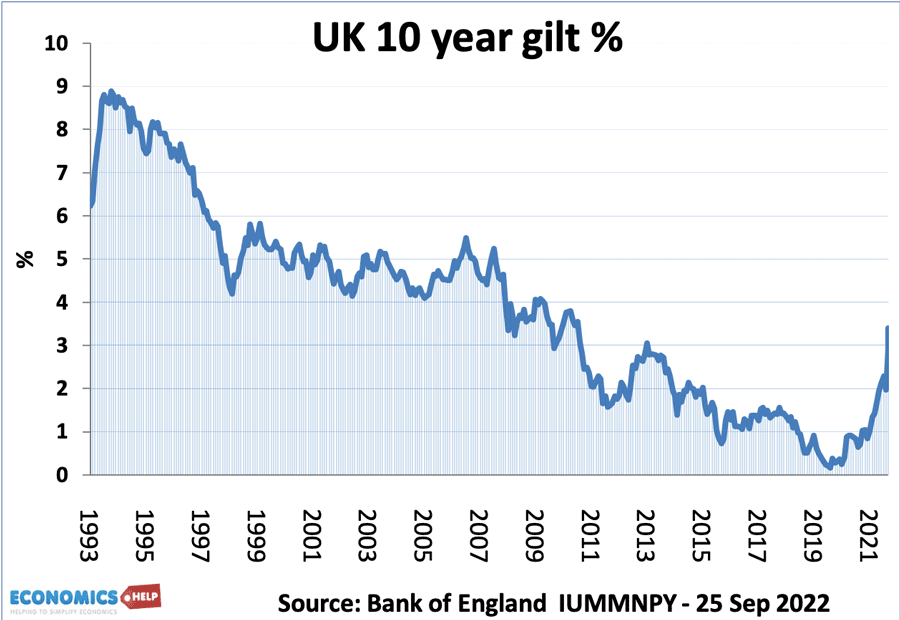

2. Bond yields still low by historical standards

Back in the early 1990s, 10 year gilt yields were in double figures. Gilt yields are on the way up (heading above 4% this morning), but they are still low by historical standards.

3. Debt maturity. The average debt maturity for UK gilts is 13 years. This is a long-time to maturity. This reduces the likelihood of an imminent crunch.

4. Global savings glut. One reason for low-interest rates in the past 15 years is a glut of global savings. This has led to relatively low global growth, but also strong demand for bonds. Although UK bonds are becoming less attractive than US bonds, there still is strong demand for sovereign debt, which will still be of some benefit to the UK, even if gilt yields need to be a little higher. Recently in August, there was still strong demand for UK Gilt sales, with bond issues 2.5 times oversubscribed.

5. UK external liabilities mostly denominated in Sterling. Most of UK’s net liabilities are denominated in Sterling, so a depreciation improves UK’s net investment position. This means a fall in the Pound does not cause a self-reinforcing cycle of deterioration in assets. (and therefore avoid currency crisis) Paul Krugman argued UK’s recent budget was terrible (Tax cut zombies attack UK / NY Times paywall), he didn’t see a currency crisis in UK.

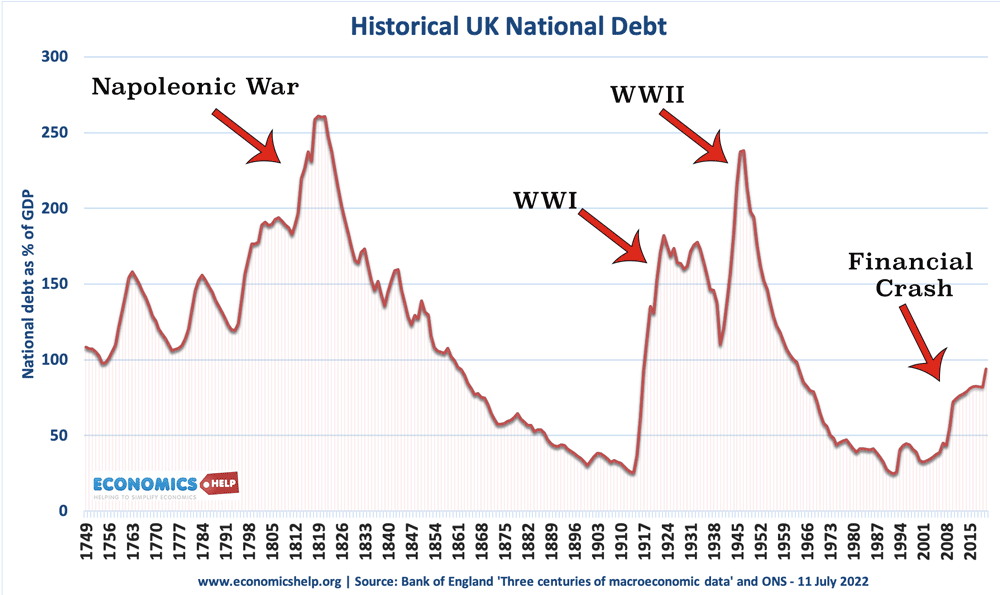

6. Debt still not high by historical standards

Whilst debt to GDP will rise to over 100% of GDP quite quickly. (and this is a rare occurrence for peacetime. The UK has had higher levels of debt in the past.

But – why growing debt does matter

1. Monetisation of debt is not possible with inflation over 10%. In the past 15 years, economists (especially of an MMT persuasion) state – that you can’t default when you have your own currency and issue debt in your own currency. However, this does have a limitation, if inflation is running at 10%, you can’t print money without causing a real inflationary problem. Already the Bank of England has begun quantitative tightening, selling bonds on the market, which increase interest rates.

In the Napoleonic War and First World War, the high UK debt did cause considerable inflation, which causes a ‘hidden default’ default through inflation. The government reduces the debt burden by reducing the real value of money and savings.

2. The inflationary impact of borrowing. The fiscal expansion is so big, it increases the potential for inflation, which will put more downward pressure on the Sterling and the need for compensating interest rate rises.

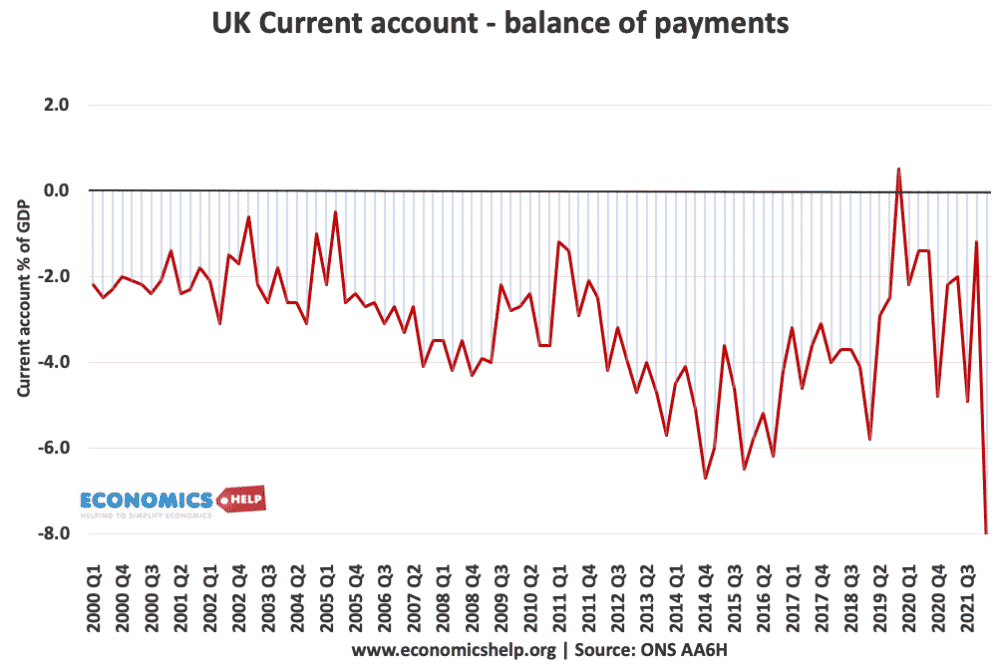

3. Level of debt is not everything. The UK required a bailout in the 1970s from the IMF. This was not just due to high borrowing, but also large current account deficit and sliding Sterling at a time when the government wished to target the exchange rate.

4. UK twin deficits

UK has a twin deficit with a current account deficit expected to rise this winter because of a rise in the value of energy imports this winter.

Demand for gas imports is very inelastic, so as their price rises, demand for other imports must fall driven by falling sterling and/or tighter monetary policy. The fiscal expansion keeps demand for imports up – putting more downward pressure on Sterling.

You don’t need a ‘Crisis’ to be a serious problem.

- Just because we might not have an actual default and collapse in sterling, doesn’t mean there isn’t a serious problem.

- The large rise in borrowing now (at a time of high inflation) will constrain future governments’ ability to spend.

- Are we getting the best value out of borrowing? Are tax cuts for high earners and corporations best for long-term growth when it could have been spent on insulation, green energy and reducing the need for energy imports?

- Despite the bailout there is still a risk of rising business failures because of rising interest rates and energy prices. An economic downturn this winter would worsen many of the government’s options.

Further reading