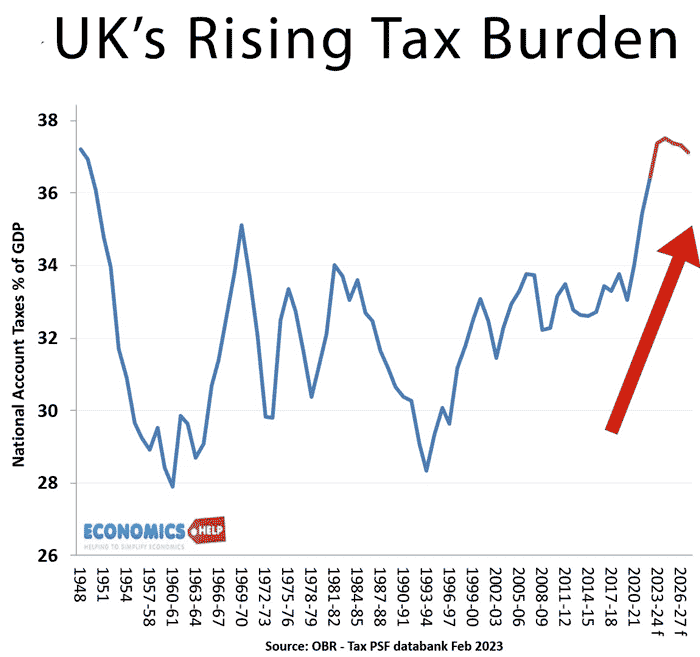

The UK tax burden has increased to the highest level since 1948. In the past three decades, the burden has risen from 28% to 37% of GDP and will continue to rise with the typical household expected to pay an extra £650 a year from April. However, whilst in 1948, the government were setting up the NHS and welfare state, 2023 has seen record waiting lists and public services under great pressure. Why have we ended up with higher tax but deteriorating public services? Is it bad luck, bad management or bad decisions?

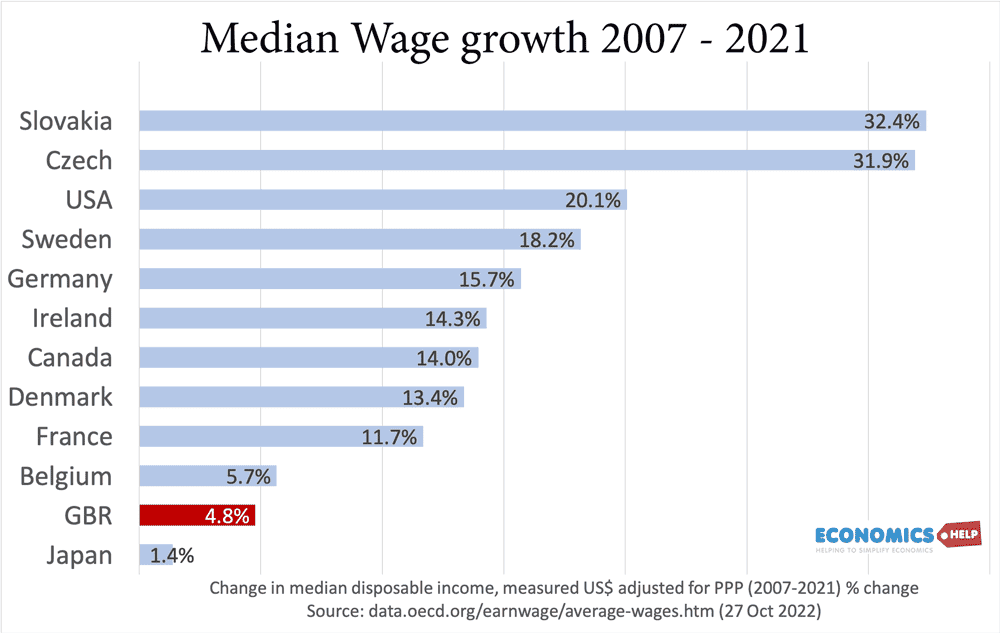

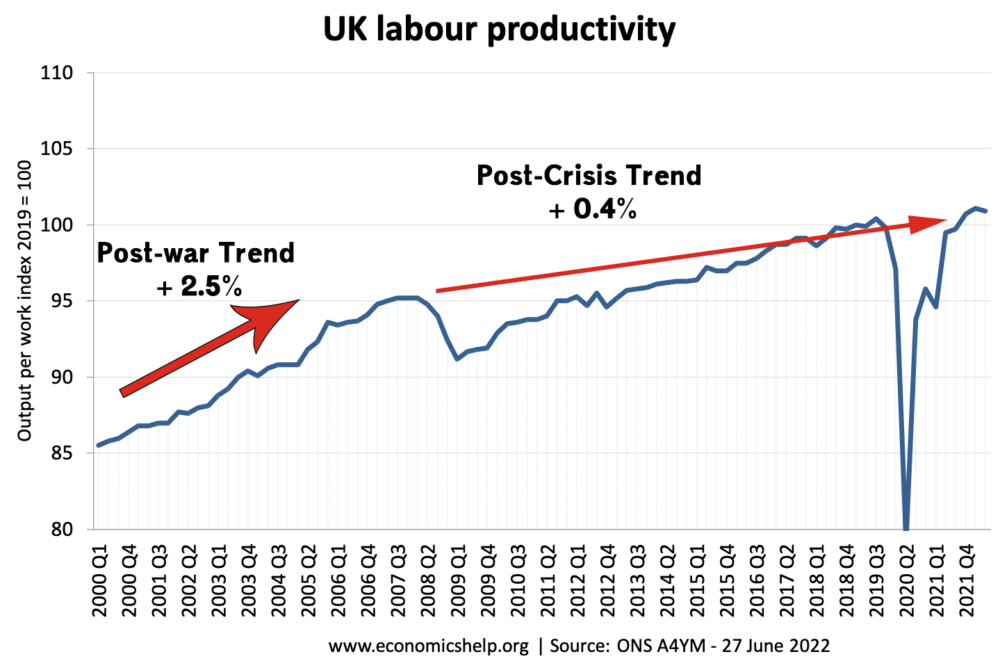

In the post-war period, the UK was growing at an average of 2.5%. Not spectacular by international standards, but enough to enable growing public spending. But, in 2007, that started to change, the UK experienced a sharp fall in economic growth, and since 2016, has performed much worse than our main competitors.

This anaemic growth means that the government receives much less tax than expected. The FT report how if UK growth had been maintained at pre-crisis levels, the average person would be a staggering £10,600 a year better off. Forecasts for 2023 and beyond remain pessimistic.

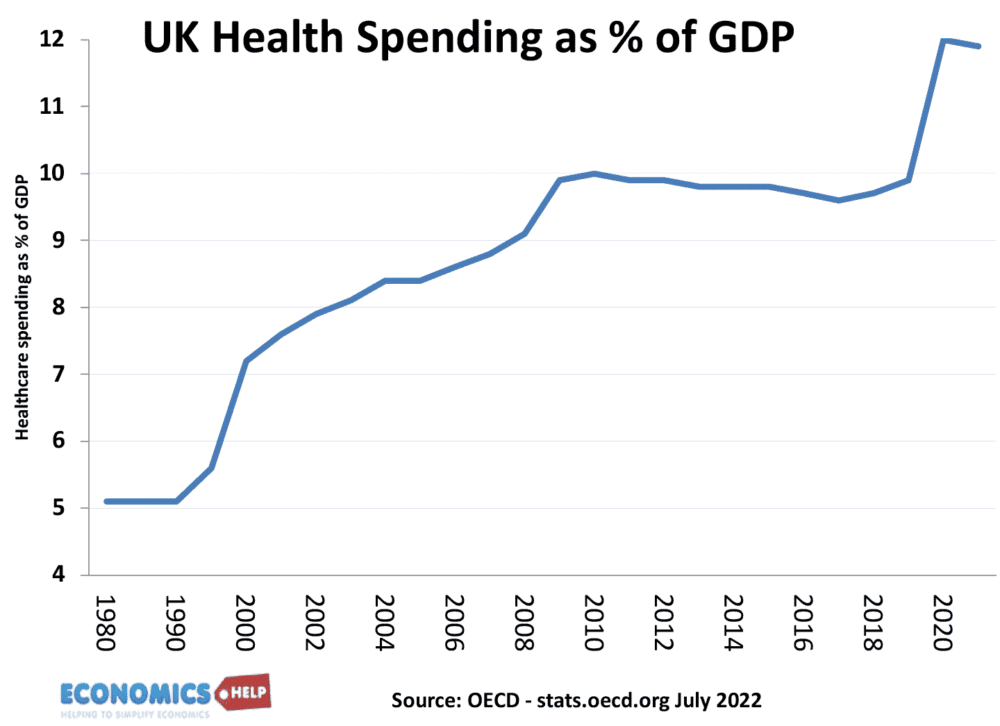

However, whilst tax revenues have fallen, our demand for health care continues to rise – an ageing population, the effects of covid, a rise in long-term sickness and new expensive treatments. This rise in health care is on top of a growing pension bill, which has soared in recent years. High house prices and rents have also caused more pressure on housing benefit.

To fill this fundamental funding shortfall, the government has tried to trim other budgets. The austerity years of 2010-16 saw falls in many government departments such as education and public sector investment. Capital spending on the NHS declined and is low by international standards. It also led to public sector pay falling behind the private sector.

With nurses seeing a 10% fall in real incomes and 20% less than private pay. However, trimming at the edges placed more long-term pressures on the system. The impact of Covid, combined with long-term funding cuts, stretched the system to breaking point, leading to a rise in waiting lists. It has also caused slower growth in life-expectancy than expected.

The big question is why is economic growth much slower? Firstly, the UK has seen a decline in previously strong industries. In the 1980s, the UK received a tax bonanza from north sea oil. Adjusted for inflation the government received around £18bn a year. The government also received a one-off bonus from privatisation. But, unlike say Norway this was not invested in public sector investment or a sovereign wealth fund, but was used to cut the tax burden. While there was talk of an ‘economic miracle’ in the 1980s, there was a considerable amount of good fortune, that would prove temporary.

In recent years, oil revenues have declined as North Sea operations have gone past their peak output, the decline has also affected GDP. The boon of privatisation receipts have also declined to a trickle. Furthermore, the 2007 credit crunch particularly affected the UK finance industry, which is a major contributor of tax revenues, since it had so many high earners. Post-2007, the UK economy has definitely struggled with a relative decline of its major industries oil, finance and continued weakness in manufacturing. Other reasons include the austerity of the 2010s. There is a link between austerity and lower growth. Cuts in government spending, where not replaced by a booming private sector. In the 2010s, the pessimism of austerity, contributed to lower growth, lower investment and confidence.

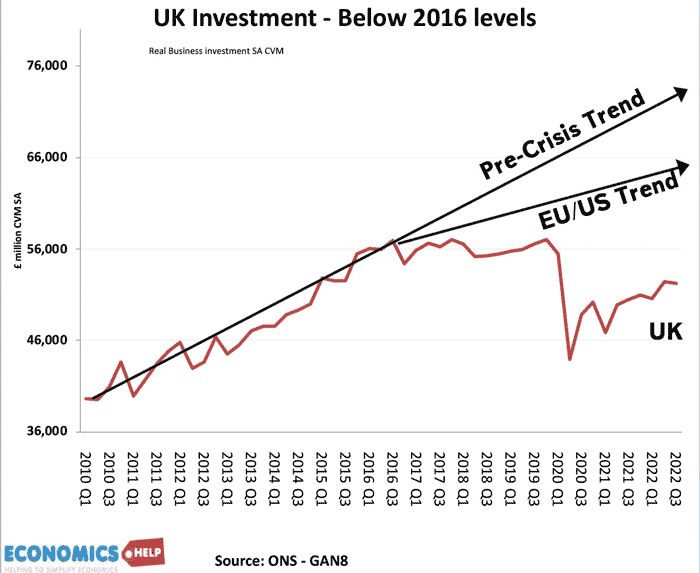

The real problems started in 2016. Firstly, the uncertainties of Brexit, changing trade rules and covid, hit business investment very hard. Whilst other countries recovered, the UK didn’t. In 2021 the UK left the single market and was replaced with a ‘hard Brexit’ which has disrupted trade much more than many businesses ever expected. The new custom rules, regulations and costs of trade have hit small and medium-sized businesses in particular. It is not just the higher barriers to trade, but the sense of constant change and uncertainty. Critics argue government policy has been prone to flip-flopping – a situation which reached a peak in the September budget of Truss and Kwarteng. The radical budget of tax cuts for the rich was rejected by the public, but perhaps more importantly rejected by the markets. Interest rates soared as the UK’s government’s borrowing suddenly looked much less appealing. Though nearly all of the budget has been reversed, it is not without damage to the UK’s reputation and has made the government tread a more cautious path in limiting the amount of borrowing. The rise in interest rates is a key reason why the government have had to increase taxes, despite the political costs.

But, it’s not just short-term problems, Other long-term problems include the UK’s planning systems, which make it easy to block or at least delay the building of housing and investment projects. It means there is a shortage of housing and office space in key regions of economic development, such as London, Cambridge and Oxford. Projects like HS2 and the expansion of Heathrow airport are symbolic of UK investment projects. They take so long to get permission and agreement that costs tend to escalate and in the end, become scaled back or cancelled. We could contrast this with France and European countries, which generally have quicker planning schemes and can get big projects built quicker.

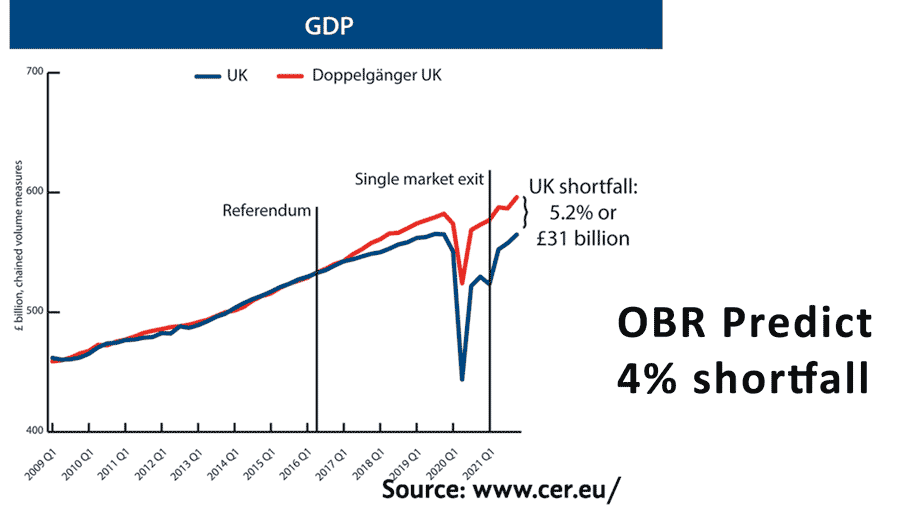

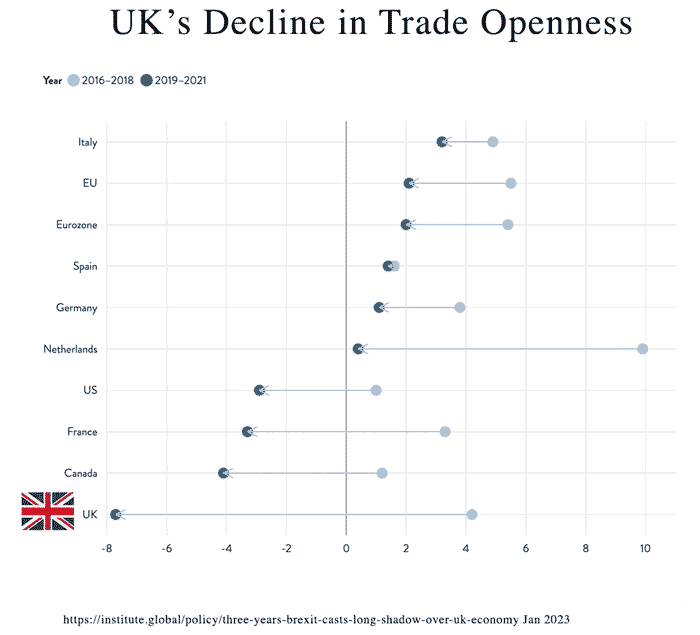

The OBR forecast the UK has lost 4% of its GDP from the impact of Brexit. The Centre for Economic Reform, claim it is closer to 5.5% loss compared to comparable countries. The impact of Brexit can clearly be seen in the shock to business investment in 2016, which has never recovered. This is a unique decline of a key factor determining long-term economic growth. The Brexit devaluation has also led to higher import prices, and cost-push inflation and exacerbated the rise in oil and gas prices during 2022. The UK used to be an economy reliant on free trade and an open economy. But, Brexit marks a fundamental shift with the OBR stating there has been a 15% fall in export/import penetration, which reflects how barriers to trade with our nearest trading partner have not been replaced with trade from non-EU countries like Australia.

Labour market

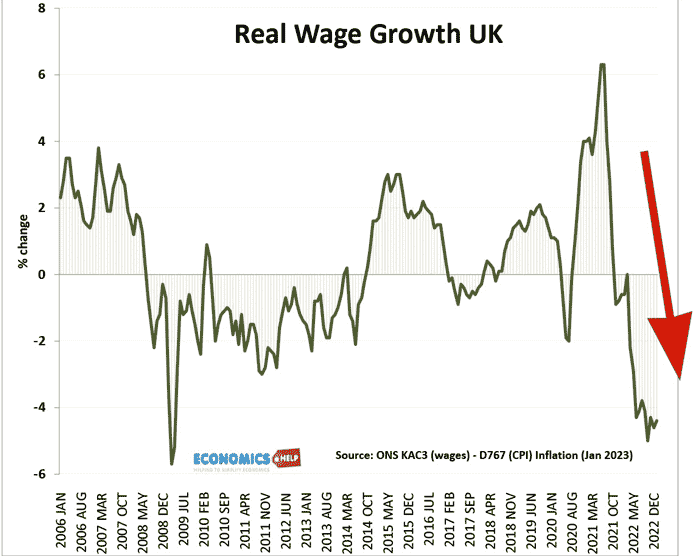

On top of all these problems, there are structural problems with the UK labour market. It is a curious mix of labour shortages and falling real wages. Textbook economics suggests that labour shortages should push up wages. But this has not happened yet. With inflation at 10% and very low productivity growth, workers have seen the biggest fall in real wages for decades.

This decline in real incomes has been magnified for public sector workers. Another area of concern in the labour market is the decline in labour participation rates. This is particularly an issue for older workers, who are increasingly leaving the labour market due to rising ill health and plans for early retirement. With the UK, like other western economies facing an ageing population, this is a concern for the future, with fewer young workers with the necessary qualifications to fill labour vacancies. The impact of labour shortages is another friction for business and discouragement to expansion.

Productivity

The impact of all these factors has been to cause record low levels of productivity growth – output per worker. Productivity growth has fallen across the world, but the UK’s record has been worse. In the short-term, the UK will also struggle to adjust to the end of ultra-low interest rates. For 13 years we have got used to interest rates close to zero.

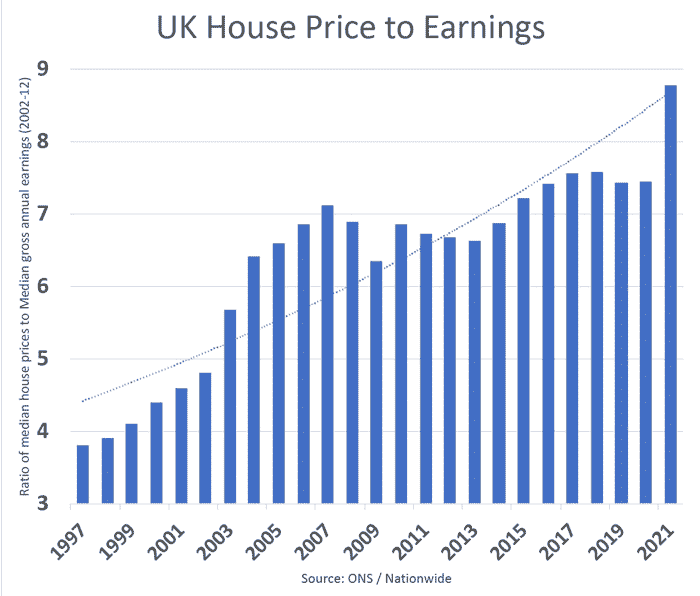

This was a key factor in pushing house price-to-income ratios to record levels, but the arrival of unexpectedly high inflation has caused a sharp rise in rates, which are causing mortgage payments as a % of income to get close to levels last since before 1991 and 2007 house price crash. The higher interest rates will catch many people out, especially when they have to get a new fixed-rate deal and find out how much costs have increased. It is expected to cause a significant fall in house prices, which will only add to negative pressures on the UK economy.

Good News?

Looking for better news, there has been a substantial fall in oil and gas prices since last summer. This is important for the UK because gas is by far the most important source of heating for households. Lower gas prices will help reduce inflation and also the cost to the government as energy price guarantees are cheaper than predicted. It is one reason borrowing has come in at a lower level than expected this year. If inflation falls rapidly to 2% as some predict (or perhaps hope), it will enable a reduction in interest rates and will end the period of falling real wages. However, whilst these temporary factors will be welcome, they do not start to address the long-term issues facing the UK economy. It is not just Brexit and Covid and oil price shocks, it goes back to the 1980s and the decline in the industrial sector and reliance on oil and finance.

Massively misleading visualisations – not starting scale at 0 leads to an distorted perception of how large increases are in the overall scale of things. A classic trick for biased editorial, or perhaps just really bad examples of how to visualise data in a sensible way.

I cannot believe taxes are higher now than in the 1940s. This misleading data is expressing taxes as % of GDP, so the phenomenom is explained by a real decline in GDP. Consider, we were still repaying war debt in 2006; and, in 1970s personal income tax was up to 80% and corporation tax 60% – both much higher than current marginal rates.

The UK economy is in free fall and will continue unless employment in non value adding services such as Civil Service, Local Authority, irrelevant non front line positions in Social Services, NHS etc. are eradicated.

Means Testing is drastically needed for all Child related payments and responsibilities returned to the shoulders of individuals and not on those obstaining from parenthood who shoulder a disproportionate tax burden, this includes free childcare and family allowances that should have been stopped years ago. There is no such thing as Child Poverty in the UK today as allowances, are if anything over generous and if such exists to the extent currently continually spouted by the Media etc. it is due to neglect and should be dealt with as such, with clothing and food voucher instead of cash payments that are obviously being misused.

To climb out of the bureaucratic nightmare we need the sort of people who do not choose to take bureaucratic jobs. An example for the NHS: take out the hospital trust CEOs and replace them with someone who has run a private hospital. NHS England should be run on the lines of a multiunit business such as Tesco. Tesco has more stores than the NHS has hospitals, yet anomalies such as unusually high neonatal deaths would be picked up and acted on much more effectively at Tesco.