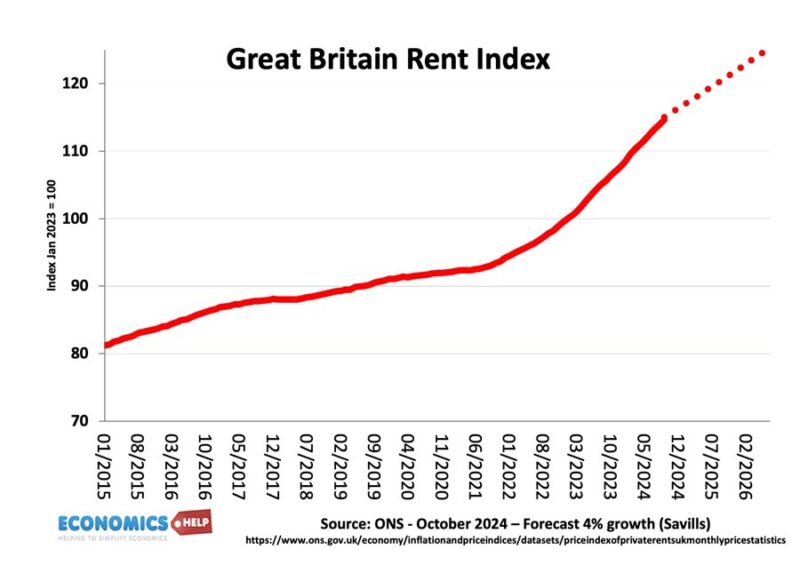

Over the past 35 years, rents have risen faster than inflation. But, even as rents reach record levels, they are forecast to keep growing.

The latest surveys show a continued mismatch between rental demand and rental supply meaning another year of inflation-busting rent rises. The problem is we have such a mismatch of supply and demand, that rents are increasingly determined by what tenants can afford. We have this unwelcome dynamic where even if wages rise, housing costs eat into any gains, leaving workers no better off.

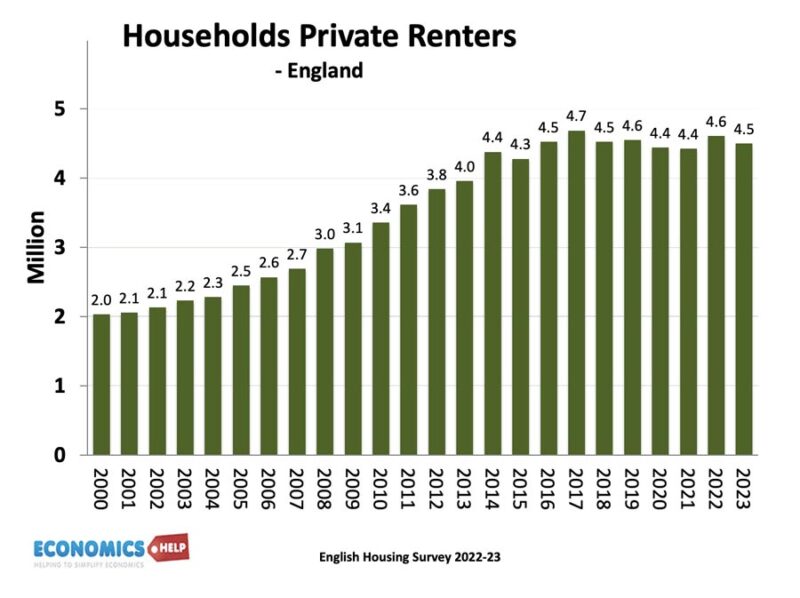

In 2000, there were just 2 million households in the private rented sector, today it is more than double at 4.6 million. Renting is now more common than buying and its expense is hitting both living standards and holding back economic growth.

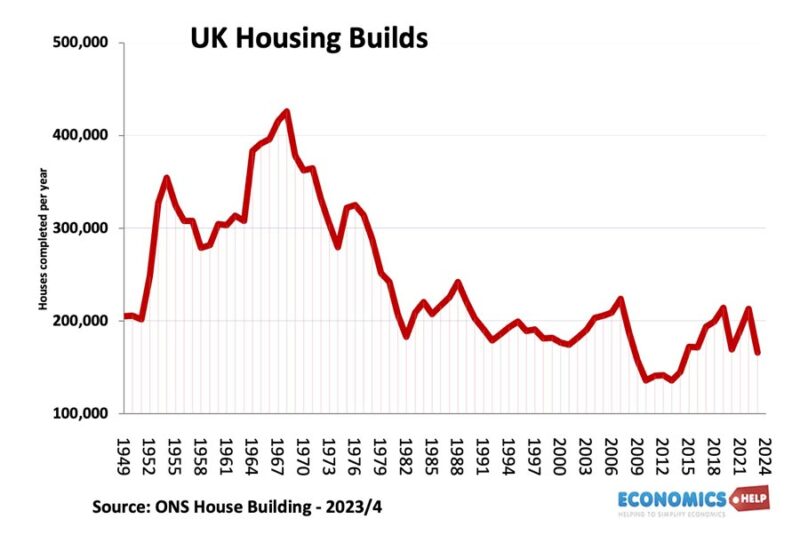

There are some solutions, we’ll look at. But it wasn’t always like this. After the war, the UK housing stock was broken, there were still many slums and some households faced paying rent equivalent to over 40% of their income. Yet, the post-war period saw something of a housing miracle.

Homebuilding rates increased and for the first time, there was mass building of cheap but still relatively good housing. By the 1960s, the UK was building over 400,000 new homes a year. Working people had access to cheap housing with rents as low as 8% of disposable income, the private rented sector went into decline.

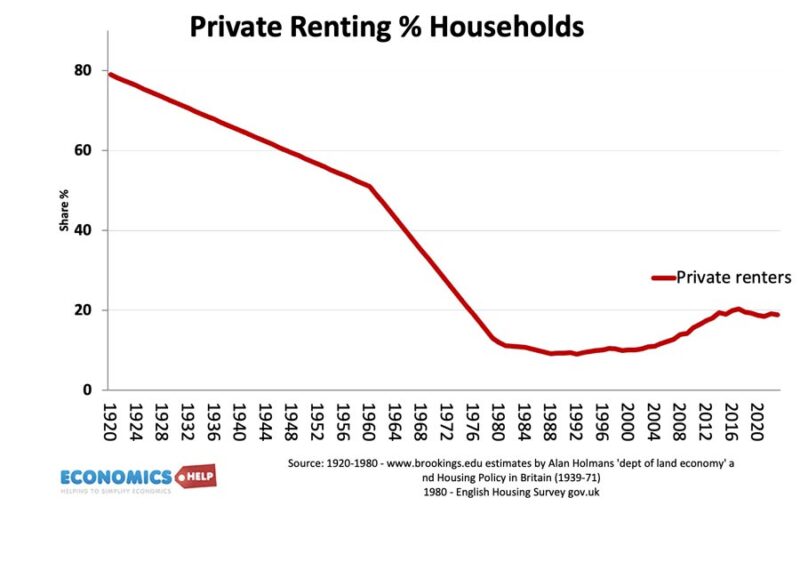

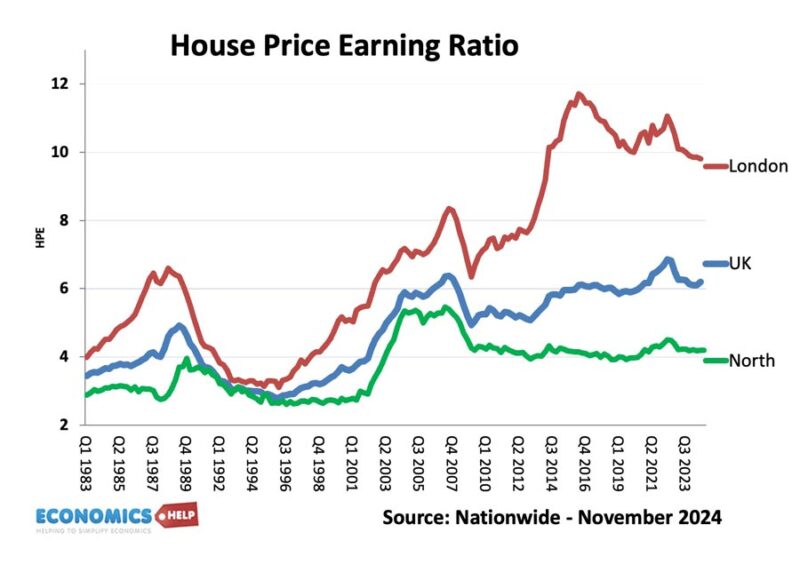

The next big change in the housing market was a surge in homebuying. After the war house price-to-income ratios were close to 7 times income. But, by the 1970s, smaller cheaper housing and rising real wages enabled more people to buy. House prices were affordable. Rising homeownership rates were then supercharged by changes to mortgage lending. Once highly regulated and restricted, the liberalisation of mortgages opened up a greater possibility for working people to buy a house. It was a grim time for private landlords, low rents, affordable houses. Many sold houses cheaply which were bough up by local councils to increase the council stocks. The share of private rented had fallen from 80% in 1920 to 9% in 1982

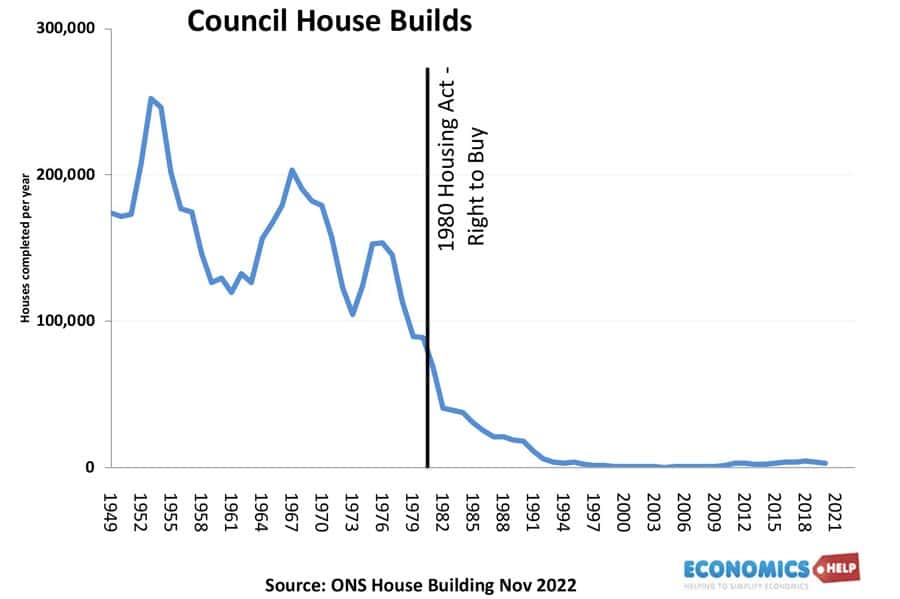

However, whilst the housing market was making great progress, in the 1980s, there was a big reversal. Firstly, the council building went into decline. Tenants were allowed to buy council houses at a discount, but, crucially, funds were not reinvested into new housing stock. As house prices soared during the 1980s, the stock of council houses fell, even as the population continued to grow. Housing was left to the private sector. Except it wasn’t a free market, because extensive planning rules and regulations meant developers struggled to build houses where demand was greatest.

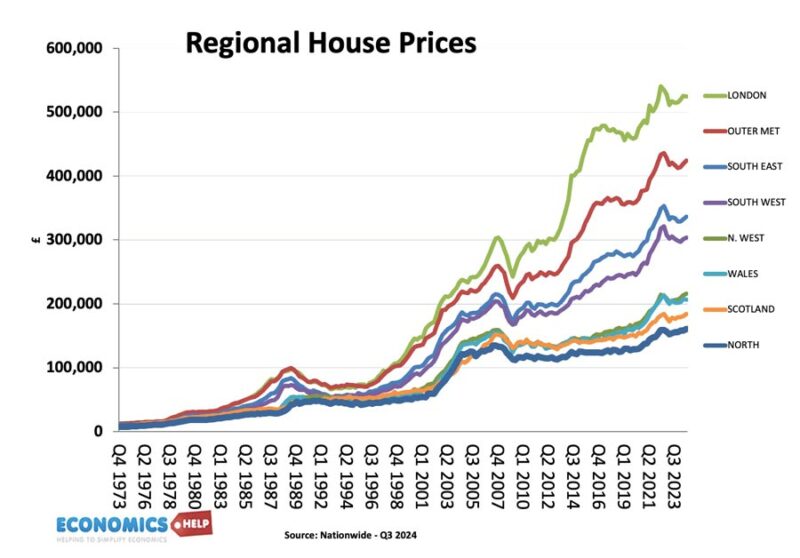

In the early 1980s, regional differences in house prices were really quite small. But, as demand rose in prosperous areas, house prices increasingly diverged. Average house prices in the north were £161,000. In London, they were over half a million. This divergence can be seen in the the ratio of house prices to income – reaching 12 in London – despite higher salaries.

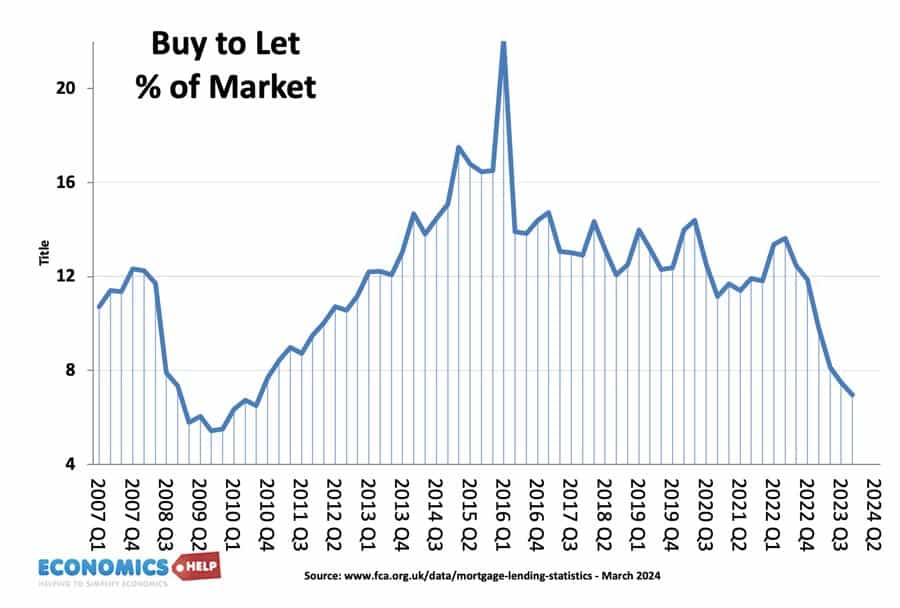

Starting from the early 1990s, there was a boom in the buy-to-let sector, helped by banks encouraging specific buy-to-let mortgages and relatively lenient tax and regulations.

As house prices rose and the population grew, many found themselves moving into the private rented sector, not by choice, but by necessity. Between 1980 and 2008, house prices soared 730%. But, the big crash of 2008 saw another major change. Freaked out by collapsing mortgage markets, the government introduced more strict lending rules, which made it harder to buy for the average household. But, with interest rates very low and an increase in money supply, banks were still lending to buy to let landlords. The Buy to Let share of the market soared – 2016 was the peak for buy to let. House prices were rising faster than inflation and the return from renting was better than keeping money in the bank at rock-bottom interest rates.

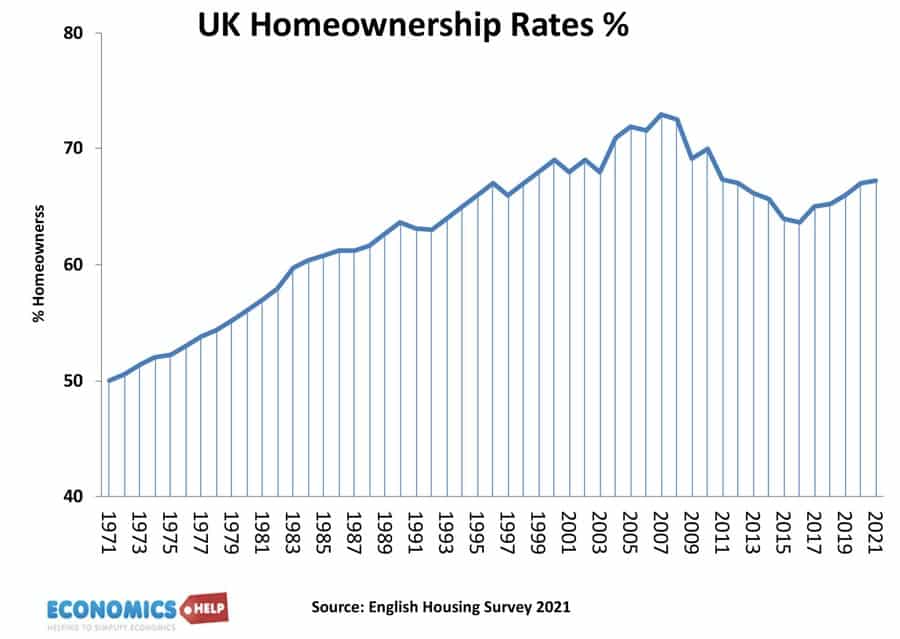

Home ownership rates

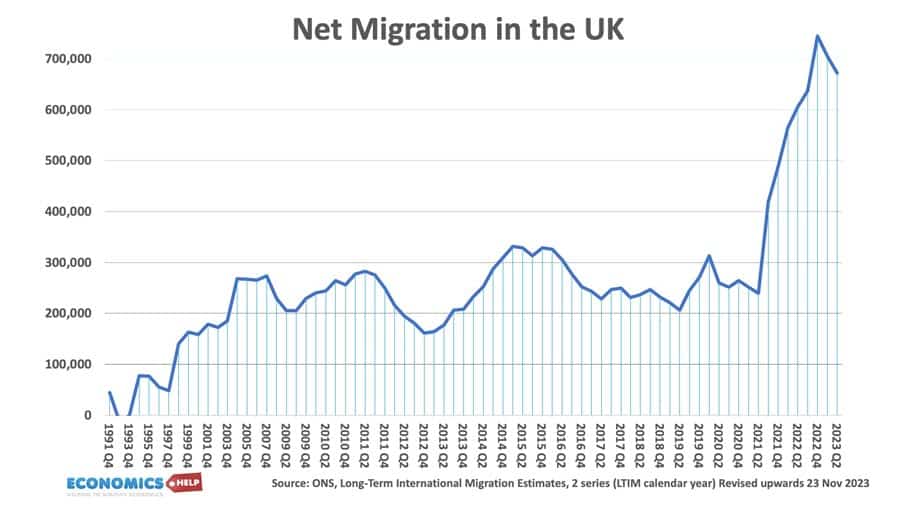

The problem is that as buy-to-let boomed the great homeownership dream of the UK was unwinding, buy-to-let investors were crowding out working families – homeownership rates were falling, especially for young people. The Conservative government began changing tax breaks for buy to let investors and introducing new regulations, which increased costs. At the same time, the population continued to rise, due largely to net migration. Rather than addressing the problem of supply, especially in the rented sector, there were a few sticking plaster policies such as help to buy, which gave first-time buyers help to get bigger mortgages, further inflation demand and prices.

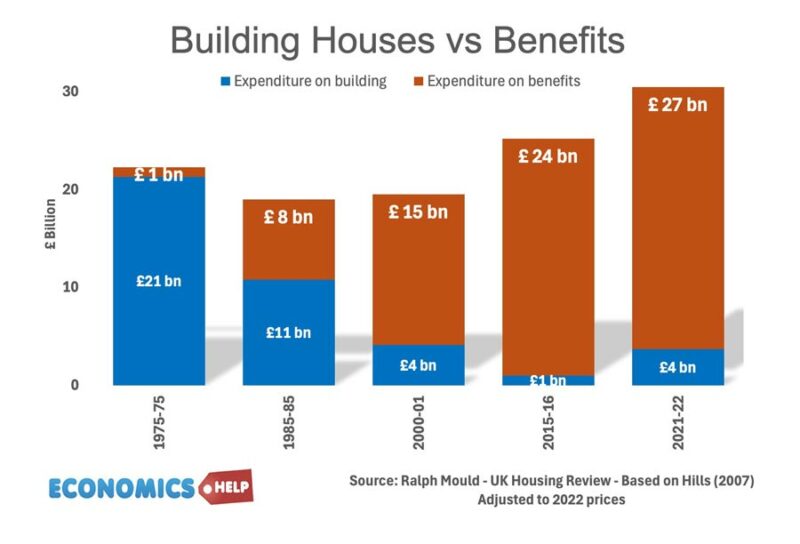

Higher benefit spending

Ironically, the rise in the cost of renting was leading to higher spending on benefits. If there is one graphs that highlights the absurdity of the UK housing market, it is the fact that in the 1970s, the government spent 95% of its funds on building houses and 5% on benefits. By 2022, it was spending 12% on building and £27bn on housing benefits. In fact, the government was so worried about the housing benefit bill, it has been capped, especially for households with more than two children. But, taking away benefits without any other policy has left many in dire straights. The UK has seen a rise in homelessness defined as temporary accommodation. This of course is expensive for local councils.

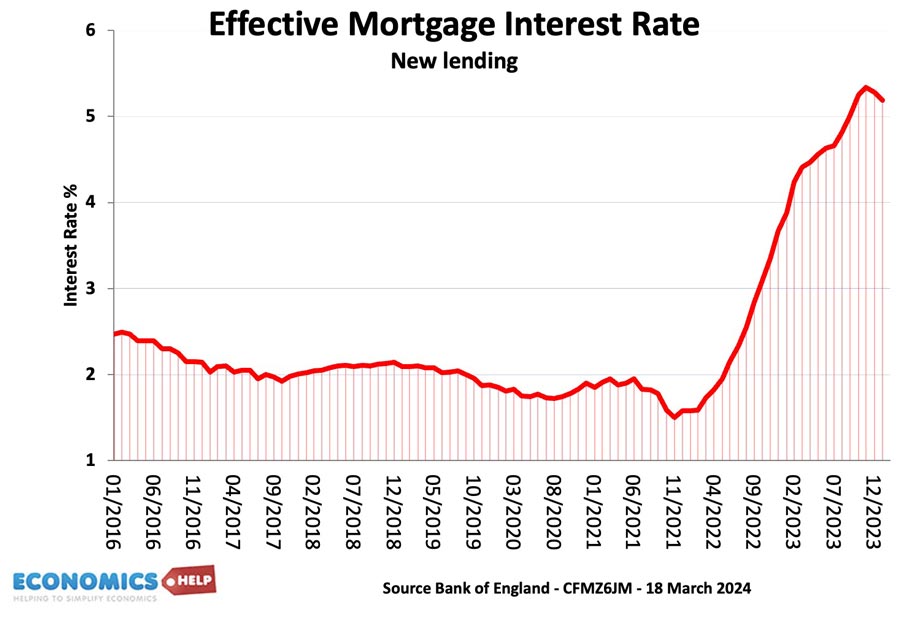

Interest Rates

But, it was the rise in interest rates in 2022, which really exacerbated the problems of the buy to let sector. The rate of return has fallen as mortgage costs rise. Even record rents have been insufficient to prevent a growing number of landlords promising to leave the sector. Landlords have been further discouraged by new legislation such as section 21 no-fault evictions and the introduction of minimum energy standards by 2030. With only 45% of private properties currently meeting the standards, many landlords may prefer to sell rather than meet upgrades, estimated to be in the region of £21 billion. Landlords selling is not helpful, when demand keeps rising. On top of that the new extra stamp duty levy for second homes is another cost for both private and corporate investors buying housing to rent.

How to Improve Rental Sector?

This is why the market is working against renters but what can be done to change the narrative?

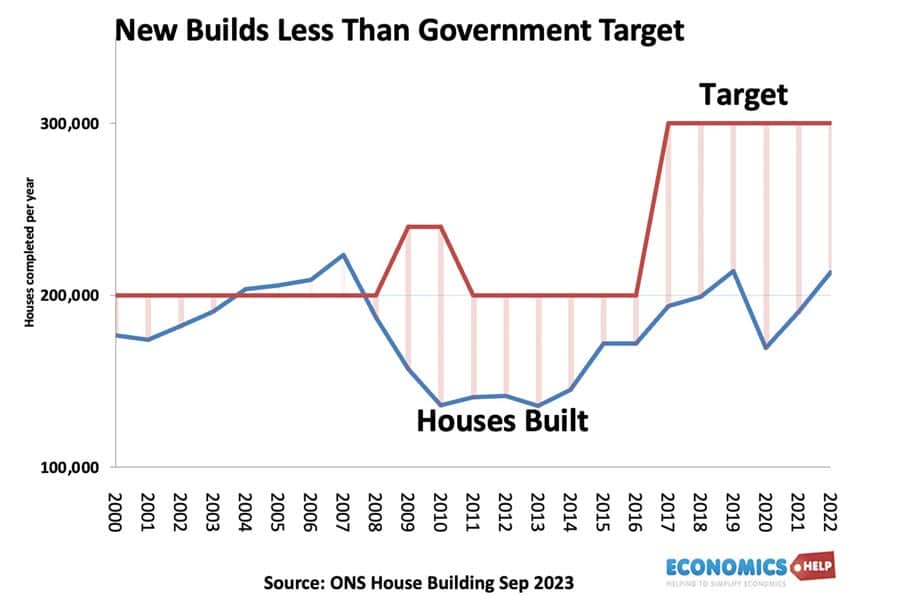

The first step the government are taking seriously is trying to build more houses. The target of 1.5 million in the next 5 years, is admirable but also a little pie in the sky. Despite changes to planning rules, the private sector will struggle to build for three reasons. Firstly, there is a relative shortage of skilled workers. Construction was heavily reliant on EU workers who have now left following Brexit. Secondly, construction costs have risen significantly since Covid, reducing profit margins. Thirdly, private firms are not in the business of meeting government supply targets, they are in the business of maximising profits, which may well mean limiting the supply of new houses. Why would they want to reduce prices?

No quick fix

But, even if a lot of houses are built, there is no magic bullet to making housing suddenly affordable. Studies suggest 1% rise in supply means house prices are around 1-1.5% less than otherwise. It means that building more houses, whilst a step in the right direction is not going to improve affordability. Build to rent is a good idea, but not currently a game changer.

Rent Controls?

What about rent controls, which have been floated as a solution to rising rents. There are different types of rent controls, but generally create winners and losers. Some tenants might get lower rent or at least smaller rent rises. But, given the propensity of landlords to leave the market, rent caps, will only accelerate the trend. Rent controls, which reduce the profitability of renting will reduce supply, meaning other tenants lose out from lack of choice. It will mean even longer queues and pressure to get properties which come on the market. Sweden has had rent controls for 100 years. Lucky tenants can get rent-controlled properties, where rents are set by collective bargaining and nationwide rules. The problem is that there is a nine-year waiting list to get into this subsidised market. Those who miss out face an entirely different rental market, where prices are much higher. In 2022, Scotland imposed a temporary rent cap to deal with the cost of living crisis, but the Scottish Property Federation claim it led to a loss of £700m of investment in the private rented sector. Also it led to a big jump in rents in between contracts.

Rent controls have to be combined with increasing supply. In the 1970s, many local councils were taking advantage of low housing prices to buy properties off private landlords to bring housing quickly into the council owned sector. This was very effective in boosting council available properties. But, given property prices today and low funds local government it is not realistic.

High Migration

High immigration has definitely exacerbated the rentral crisis because recent migrants are much more likely to be in the private rented sector. The scale of new households in recent years is a major factor behind rise in demand. Promises to reduce immigration have often fallen as flat as promises to build more housing. But, a substantial drop in net migration would give the housing market some more breathing room. Although ironically, if you wanted to increase building of new homes, visas for construction workers are needed.

A final point is that renters are traditionally less politically influential than homeowners. Government policy in the past four decades has often prioritised homeownership as the ultimate goal, but given the current situation, private renters are a much bigger voting block and without big change will see living standards continue to be damaged by the housing crisis.

In the short-term, the easiest way to reduce the real crisis of affordability would be to increase housing benefits in line with rental inflation – even if the prospect of government subsidies to private landlords may not be welcome.

Related

Sources:

From 1989 to 2023 annual rent inflation averaged around 3.71% in the UK

From 1989 to 2023 rent inflation has beaten general inflation by around 0.91% annually

In the last 10 years from 2013 to 2023, average rents have increased by around £569 (or 121%)

If rents increased by an average of 3.71% over the next 25 years, rents would be around 140% more than they are today