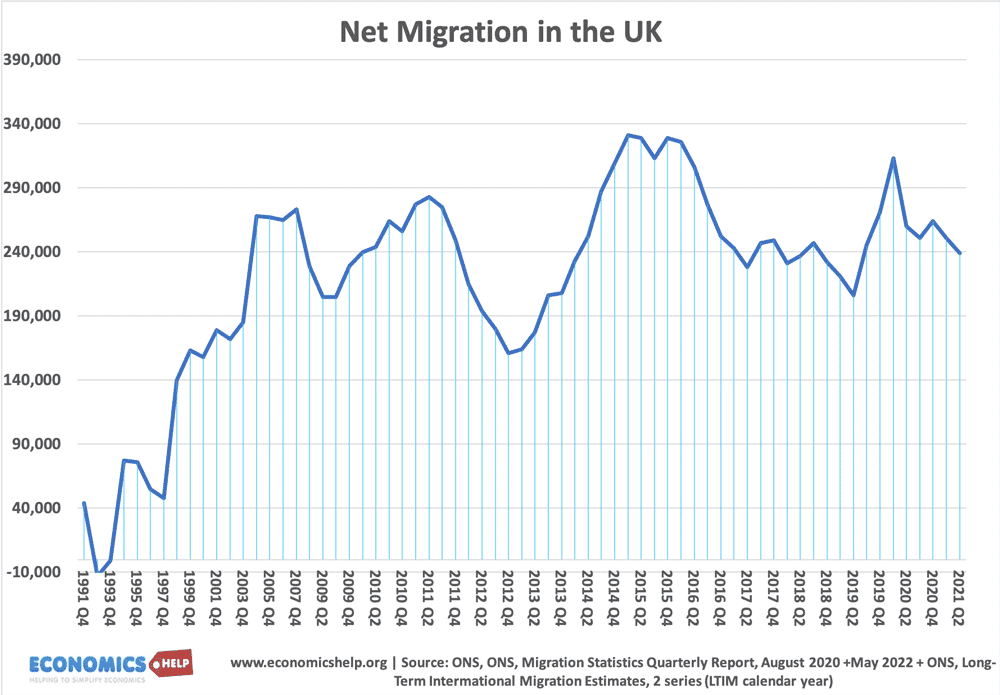

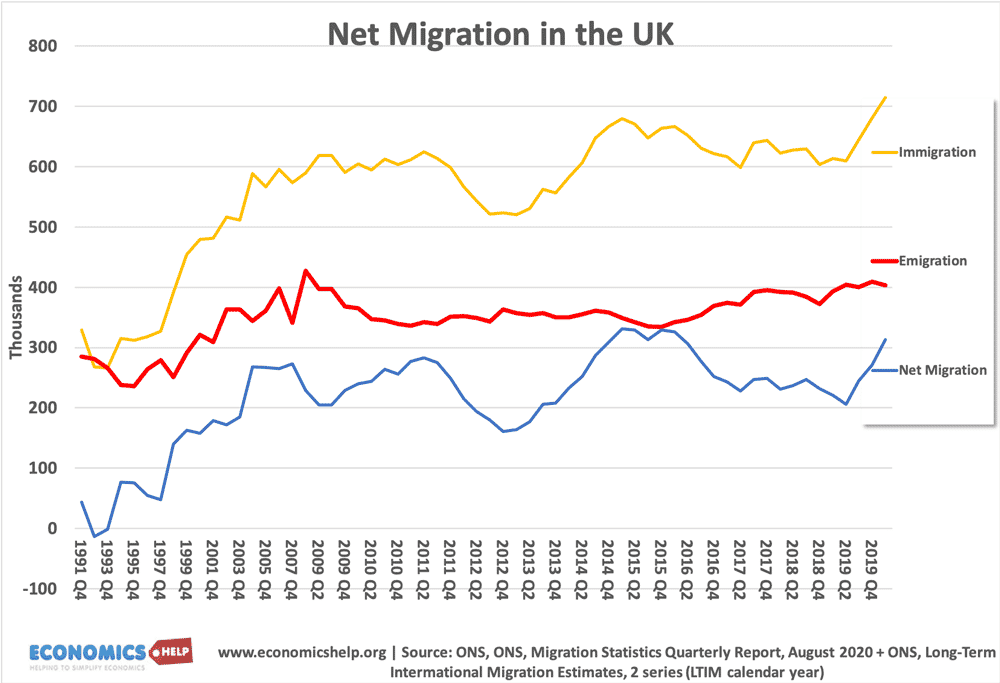

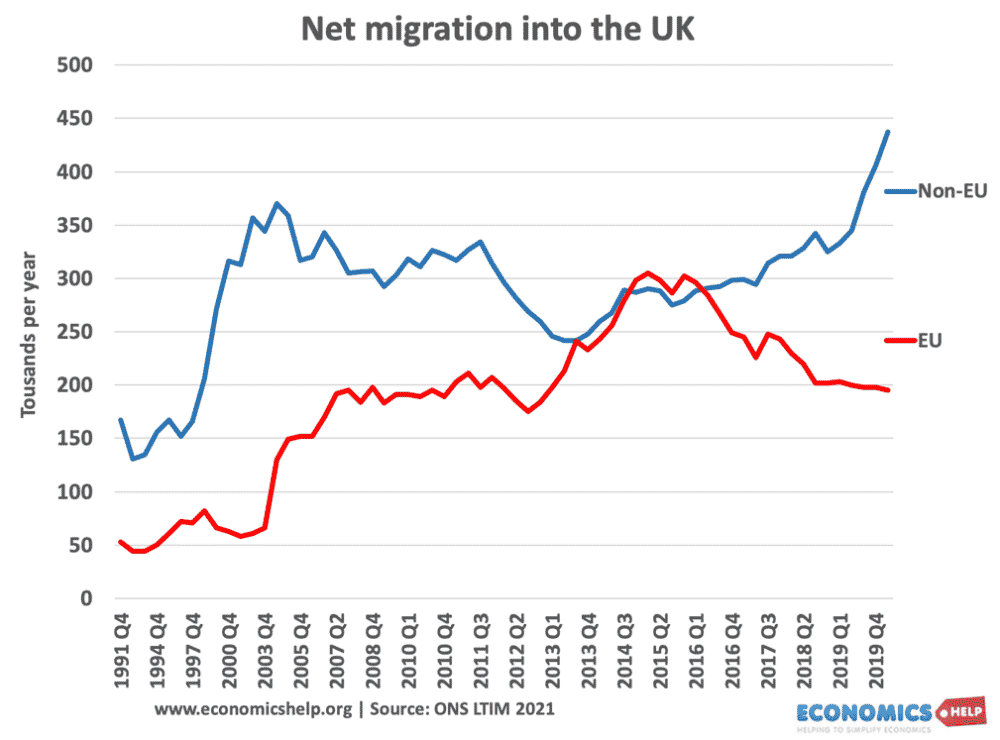

In the past two decades, the UK has experienced a steady flow of net migrants into the economy. The 2016 Brexit vote has led to a sharp fall in net EU migration, but to a large extent this has been offset by a rise in non-EU migration. This net migration has had a wide-ranging impact on the UK population, wages, productivity, economic growth and tax revenue. Does net migration benefit the UK economy?

- In 2021, Net long-term international migration was estimated to be +238,000 in 2016.

- In 2021 Q4, there were 18.766 applications for asylum.

- In 2019, there were 9.5 million people born outside the UK (estimated 14% of the UK’s population.) (5.8 million, non-EU, 3.6 million EU)

Inflows and Outflows

- In 2019, the top 6 countries for the source of migrants was India, Poland, Pakistan, Romania, Ireland.

EU vs Non-EU immigration

Traditionally non-EU immigrants are more likely to come for family reasons, whilst EU migration has been focused on work.

Impact of Net Immigration on UK Economy

1. Increase in Labour Force

Migrants are more likely to be of working age. The majority of migrants come for work or study (students) They may bring dependents, but generally net immigration leads to an increase in the labour force, a decline in the dependency ratio and increases the potential output capacity of the economy.

2. Increase in aggregate demand and Real GDP

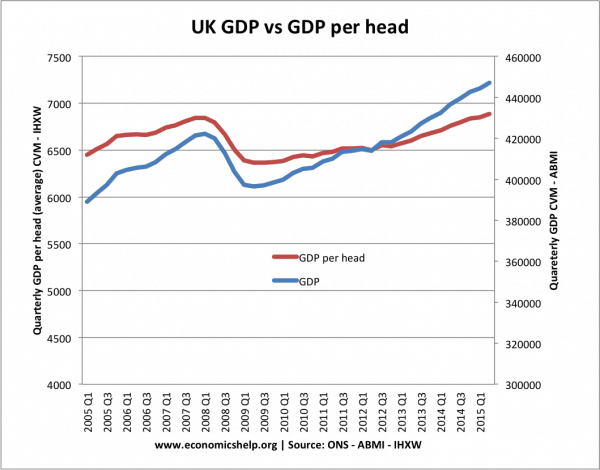

Net inflows of people also lead to an increase in aggregate demand. Migrants will increase the total spending within the economy. As well as increasing the supply of labour, there will be an increase in the demand for labour – relating to the increased spending within the economy. Ceteris paribus, net migration should lead to an increase in real GDP. The impact on real GDP per capita is less certain.

In fact, net migration can make economic growth look stronger than it is. In the period 2005-2015, UK real GDP has increased significantly faster than GDP per head. See GDP per capita for more info.

3. Labour Market Flexibility

Net migration could create a more flexible labour market. Migrants will be particularly attracted to move to the UK if they feel that there are job vacancies in particular areas. For example, during the mid-2000s, there was a large inflow of workers from Poland and other Eastern European economies – helping to meet the demand for semi-skilled jobs, such as builders and plumbers. The government has also sought to attract migrants from various countries to meet shortfalls in job vacancies in key public sector jobs, such as nursing.

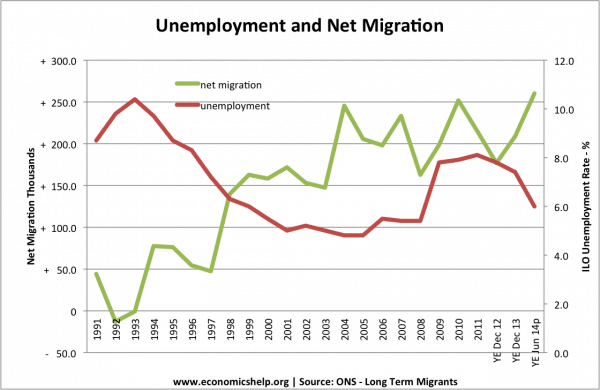

- In theory, a period of higher unemployment might discourage migrants (this has occurred in the case of Ireland). However, the UK aw continued net migration despite higher unemployment 2008-12. Since 2012, unemployment has fallen considerably and migration has remained fairly constant.

4. Positive impact on the dependency ratio

With an ageing population, the UK is forecast to see an increase in the dependency ratio. However, net migration helps to reduce the dependency ratio. Migrants are more likely to be a source of working-age people, and this helps to reduce the ratio of retired to working people. The Migration Observatory reports, that in 2019, 70% of the foreign born were aged 26-64, compared to 48% of the UK born (link). This younger population has benefits for the government’s budget. If migrants are of working age, they will pay income tax, VAT – but will not be claiming benefits.

5. Impact on particular sectors

An important reason for net migration is higher education. In 2019/20, according to Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) there were 556,625 international students (link), studying in the UK. These students may not show up in long-term migration trends. But, the short-term effects are quite important. The London Economic analysis estimate that students of 2018-19 contributed a net £25.9 billion to the UK economy (link – pdf). A very significant contribution. These payments also help to finance higher education for domestic students.

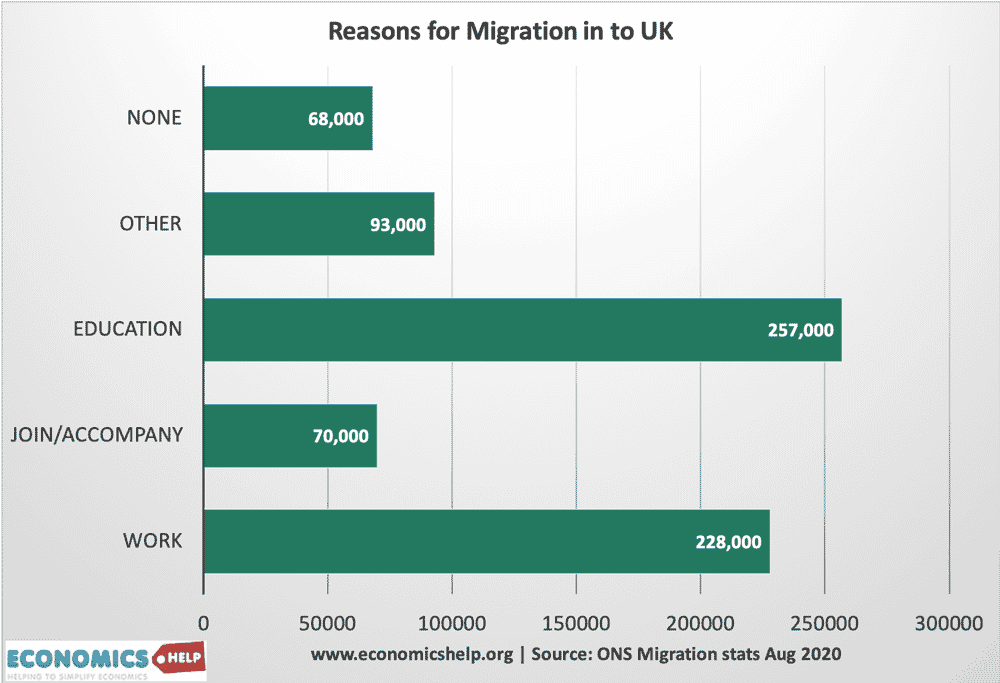

The latest ONS report suggests formal study is the biggest reason for net migration into the UK. See also: reasons for net migration into the UK

6. Social issues

Another issue felt keenly in the UK, is the concept that we are already ‘overcrowded’ In this case, a rapid increase in the population due to migration could lead to falling living standards. For example, the UK faces an acute housing shortage, but also an unwillingness to build on increasingly scarce green belt land. In many cities, it is difficult to build more roads because of limited space. The increased population could increase congestion and urban pollution. Therefore, the increase in real GDP has to be measured against these issues which affect the quality of life.

7. Economies of scale

Others may argue that concepts of ‘overcrowding’ are misplaced. In the nineteenth century, people were already worried about overcrowding. But higher population densities are in one sense more efficient and have a lower environmental impact. Other countries like Belgium have an even greater population density than the UK. Also, if migrants help to grow the economy, there will be more tax revenue to finance public infrastructure.

8. Welfare benefits

A popular idea is that immigrants are more likely to receive welfare benefits and social housing. The suggestion is that Britain’s generous welfare state provides an incentive for people to come from Eastern Europe and receive housing and welfare benefits. While immigrants can end up receiving benefits and social housing. A report by the University College of London, suggests that :

- However, despite the positive figures in the decade since the millennium, the study found that between 1995 and 2011, immigrants from non-EEA countries claimed more in benefits than they paid in taxes, mainly because they tended to have more children than native Britons.

In recent years, claiming unemployment benefits in the UK is quite strict – the claimant count measure of unemployment is much less than the labour force survey (see: Unemployment stats). People have to prove they are looking for work. Also, the criteria to be given an immigration visa from non-EU countries is increasingly strict. The migrant often have to show they have a degree of savings or an offer of a good job. The UCL report on immigration suggested that immigrants tend to be more highly skilled than native workers.

- In 2011, 32% of recent EEA immigrants and 43% of non-EEA immigrants had university degrees, compared with 21% of the British adult population.

Does Immigration Cause Unemployment?

No clear link between migration and unemployment. Net migration occurred with falling unemployment 1991-2005, but rising unemployment from 2008-12. The fall in unemployment since 2012 may have attracted more migrants coming to work.

A common question people often ask – is whether immigration causes unemployment? Migrants have often been blamed for ‘taking our jobs’ – especially in periods of high unemployment, and in local areas of above-average unemployment.

Firstly, net migration is compatible with low unemployment. Net migration helped the US population to increase drastically around the turn of the century, but this didn’t cause unemployment. Migrants bring both an increased supply of labour and higher demand for labour. In the 1990s, net migration was consistent with falling unemployment in the UK.

However, in periods of high unemployment, it may be much more difficult for migrants to find work. This may be exacerbated if the migrants have poor English, low skills and or suffer racial discrimination. In this case, net migration could add to the unemployment problem. However, the underlying cause of unemployment is not net migration, but the recession.

Another factor that determines the impact on unemployment is the skills and qualifications of immigrants. If migrants have low skills, they are more likely to experience structural unemployment. In the 1950s, immigration into the UK from the Caribbean was encouraged for manual labour (driving buses e.t.c.) to fill job vacancies. However, when the period of full employment ends, migrants may be more liable to be unemployed, if they lack the skills to find new work.

The impact on unemployment in the current crisis depends on the type and skills of workers who are migrating into the UK.

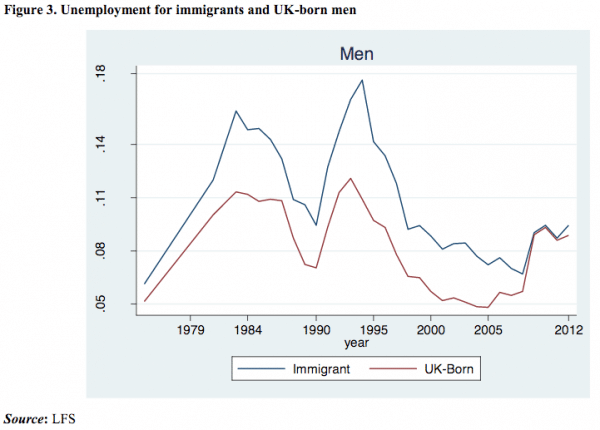

This shows that the unemployment rate for immigrants tends to be higher than for UK born workers. This gap is especially true during recessions. One reason put forward is that immigrants tend to be more likely to be working on short-term contracts, and so in a downturn are more likely to be laid off.

Does Immigration Push Down Wages?

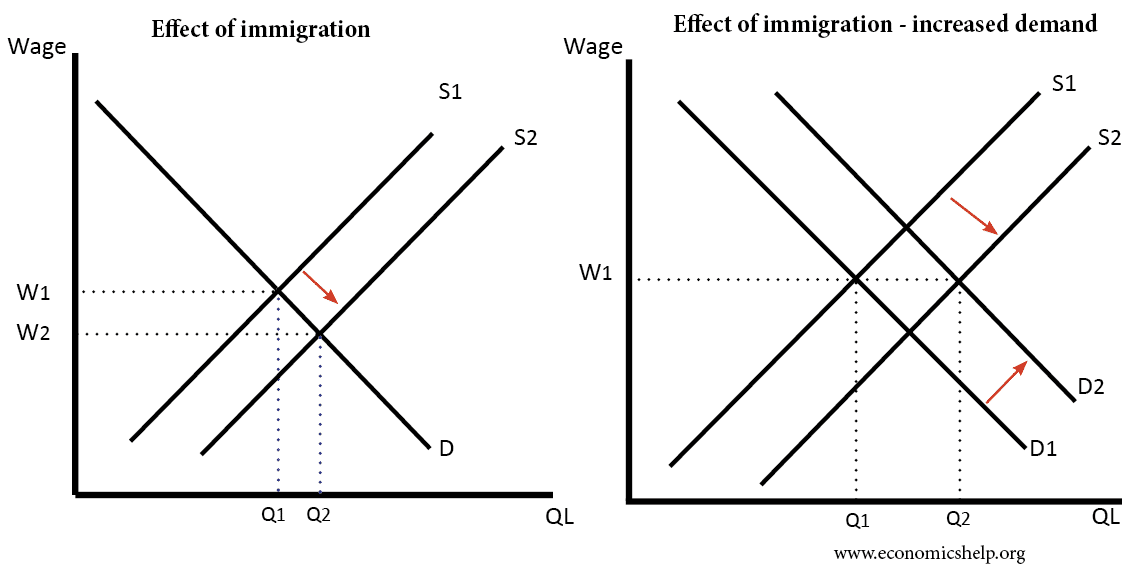

From one perspective an increase in the labour supply may push down wages. This is especially true if migrants are keen to accept lower wages (e.g. willing to bypass traditional union bargaining). However, again, net migration doesn’t have to push down wages. The massive immigration into the US, during the twentieth century, was consistent with rising real wages. Increased migration, will also affect demand for labour due to higher spending in the economy. Immigration increases labour supply – but also increased labour demand.

However, particular labour markets may notice lower wages if there is a concentration of immigrants willing to work. For example, if wages are high in a particular agricultural market, migration from a low-income country may lead to falling wages in these specific markets.

Also, some migrants may be more vulnerable and more willing to work in the black market (e.g. accept a wage below the equilibrium).

Further reading: Lump of labour fallacy – the fallacy that increased labour supply always pushes down wages.

Bank of England study on wages and immigration

A Bank of England found a rise in immigration had a tiny impact on overall wages – with a 10% increase in immigration – wages fall by 0.31%. However, the negative effect was greater for semi/unskilled workers in the service sector, with a 10% rise in immigration reducing wages the equivalent of 2%. B of E report. However, this explains only a small fraction of the real wage decline since 2007.

Video on Immigration

Evaluation of Immigration

The impact of net immigration depends on:

- The skills and qualifications of migrants. The UK is increasingly strict on allowing only skilled workers.

- How easy do migrant find it to assimilate in the destined country? E.g. in the 1950s and 1960s, migrants from the Indian sub-continent / Caribbean may have found it more difficult to find employment due to poor English / racial discrimination.

- It depends on the age profile of migrants. If a high % are young workers, then this can help reduce the dependency ratio – a crucial issue for the government budget.

- It depends on the current economic climate. In a recession, migrants will find it harder to gain employment.

- It depends on the type and skills of migrants. Migrants from Eastern Europe may be more flexible and return home if the economic situation deteriorates. Low skilled migrants are more likely to be structurally unemployed.

- Migrants can be a source of foreign income, e.g. tuition fees from foreign students. However, migrants may also send a substantial portion of their earnings to relatives abroad – reducing the wealth of UK.

- Can the Economy absorb a greater population? For example, what are the impact on public services, levels of congestion, and housing?

Impact of Immigration on housing

Positive net migration levels are a significant factor in increasing the number of households in the UK. Given limited housing supply (and difficulties of increasing supply), this is putting upward pressure on UK house prices and the price of renting.

Related

- Reasons for net migration into the UK

- Immigration and the black market

- Flexible labour markets and immigration

- Long-term migrants data at ONS

NOTE: EEA – European Economic Area – EU, plus EFTA countries Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein.

This site is appears to be less about objective economics and more about pushing pro-EU propaganda. For example, it quotes studies produced by UCL’s immigration research department (CReAM).

However, the author of this article appears to be unaware of the fact that CReAM’s studies have been discredited by a number of eminent statisticians (including UCL‘s own Emeritus Professor of Statistics). The criticisms are extremely serious.

Professor Mervyn Stone and others refer to the use of underlying crude assumptions, an all-embracing approach, the absence of sensitivity tests and the study being driven by a desire to prove a pre-determined conclusion.

He goes on to accuse Dustmann and Frattini of using questionable methods and having an inadequate understanding of the data, thereby significantly overstating their case. ‘’Small changes to large assumptions about the claimed benefits could make the supposed positive contribution of EU migrants disappear, and in fact turn negative.’’

The CReAM studies also totally ignore a number of costs arising from large-scale immigration. For example, they takes NO account of costs such as welfare benefits or social housing provided to displaced British workers. These costs run into billions and would almost certainly wipe out the modest gains asserted by Dustmann and Frattini.

There are other problems with this article. For example, using US migration flows in the early and middle 20th century as a comparator to 21st century Britain! But as this comment probably won’t even appear, I won’t waste time going over all the other issues.

But see http://creamcomments.blogspot.co.uk/2014/01/there-are-no-schoolboy-errors-in-our.html

The main conclusions appear robust

Terry, you claim that “The British cannot afford to buy in London, not even rent, it is too expensive. How come Muslims can take up residence in the Capital, where does their wealth come from, British social security payments?” Actually, lots of British people can afford to buy in London, and lots of Muslims (British or otherwise) can’t. Also I very much doubt that many people, British or otherwise, get rich from social security benefits. Where on earth did you get your statistics from?

Terry has no statistics or studies to support his assertions. He is regurgitating the Daily Mail and Express, who made it all up for people like Terry.

I don’t think Terry has ever been to London. If he had he’d know that, overwhelmingly, the people of London are not wealthy. He’d know they struggle to pay their mortgages, food bills, energy bills, local taxes, local parking, travel costs… like everyone else.

Terry would also know, if he’d ever been to London, that it’s the most cosmopolitan city in the world. The wealthiest people in London, apart from those who work in the City, and a few oil-rich Arabs in Knightsbridge, are Russian and Chinese businessmen who tend not to be Muslim.

Terry should also know that less than 5% of the UK population is Muslim, and that about 40% of the UK’s Muslims live in London – mostly in the poorest boroughs like Newham and Tower Hamlets.

But Terry doesn’t know any of this because the Terry’s of this world have their information and preferred narratives fabricated and assembled by the UK’s populist press, to suit the agenda of the non-dom, billionaire, tax-avoiding UK populist press owners.

Looking at longer GDP stats for the UK, there is no evidence that immigration has boosted or accelerated the growth of our economy. It appears that it simply proves that, on average, to succeed in work it doesnt matter where you come from or how skilled you are as most jobs don’t need a particularly high skill level.

If immigration was needed, we should see an acceleration in our GDP and a deceleration in the GDP of countries who’ve provided immigrants. There is no such effect. If supposedly highly skilled immigrants all left and were replaced by supposedly lazy Brits, I doubt we would spot any change, as the reverse process made no difference.

Louis Walker is rather harsh about this website, which I think is distinguished for its clarity, but is factually correct in noting the statistical criticisms by their professorial colleagues of the Dustmann/Frattini report (Immigrant Fiscal Contributions 2001-2011), particularly Mervyn Stone to which I would add the work of Robert Rowthorn (Emeritus Economics Professor at Cambridge) in his 2014 report. However the continued general acceptance of the fiscal contribution of immigration, notwithstanding that even Dustmann quantifies the cost of earlier non-EU immigration at £90 billion from 1995-2011, fails to address the the issue of the public expenditure shortfalls right across those areas where immigration should have required such expenditure to increase. The perverse effect of this shortfall is to increase the apparent fiscal contribution of immigrants, and indeed all inhabitants, by the simple expedient of not actually spending the contribution on those areas which need it.

Nowhere is this economic illiteracy more obvious than housing. The much quoted requirement to build 240,000 houses per annum is largely based on the forecast of household formation from the Department of Communities and Local Government with a 2012 base year and a principal population projection based on net immigration of 165,000 annually to 2031. At that level the DoCLG concludes that about 40% of household formation is due to immigration but, adjusted for their larger households, means that about 83,000 new houses annually are required solely to keep up with immigration. At £250,000 per unit that is over £20 billion annually that has to found to stand still. (Dustmann’s EU immigrant challenged contribution ran at just £2 billion annually) Last year net immigration was 300,000, 80% greater than the DoCLG projections. The cost of properly housing all in our nation is rising exponentially and is becoming impossible to resolve by any remotely conventional policies.

Half of my family is black. I am acutely aware of anti-immigration rhetoric but, as a member of a well known economics institution, even more aware of the economic dynamics transferring housing capital from many in my family to the wealthy. In his evidence to the Treasury Select Committee Steven Nickell of behalf of the OBR (minutes published 13.02.2015) said that the general consensus was that we could not say whether immigration was overall beneficial to the UK or not, a position which has remained academically unchanged for some time. (see CReAM 2012 Ian Preston and Migration Advisory Report July 2014 which concluded that the main beneficiaries were the migrants themselves and the owners of capital)

We must all draw our own conclusions as to why uncritical support of immigration by the owners of capital, exemplified by the CBI, continues to be the default position of broadcasters and most of the press who seemed to have suppressed the old journalistic maxim of ‘follow the money’. To find who is making money out of immigration is where to start questioning current received opinions as to who actually benefits.

One half of my family is black. I am acutely aware of anti-immigration rhetoric but I am even more aware of the long term transfer of housing capital

from working families to those who already own capital with immigration being a very significant agent, together with the ‘dampening of wages’ acknowledged by Steven Nickell in his evidence for the OBR to the Treasury Select Committee. He took the view that the “general consensus was that immigration may be a little bit good or a little bit bad but that the evidence is not fantastically strong either way”. This position is entirely consistent with all academic studies, including CReAM in 2012 (Ian Preston’s report on economic effects of immigration on UK) and David Metcalf’s

Migration Advisory Committee July 2014 report on unskilled migration which drew the conclusion that the principal gainers were the migrants and the owners of capital.

We must all draw our own conclusions as to why the uncritical support of immigration by the owners of capital in the UK, exemplified by the CBI, continues to be the default position of broadcasting and most newspapers.

Informative and fairly unbiased. Louis most of the data was from ONS it seemed? It could be argued your comment is purely from an anti-EU standpoint.

Thanks for the information, especially highlighting the fact that so much migration into the UK is to do with study, which brings millions of pounds into the economy. I am interested to know if there is any way to calculate how much money has come into the UK due to rich migrants fleeing war zones in the Middle East. My local neighbourhood has seen a noticeable influx of rich Iraqis and later rich Syrians over the last 15 years so I often wonder how much the UK profits from these wars. Also, I recently read an article about how instability in Turkey was leading rich Turks to invest in more property in London, and in many cases they were thinking of sending their children to university in London. I think the UK is seen as a safe bet in times of global instability.

Queries on Grubb:

Stone and Rowthorn are outliers in terms of researchers, their views are not definitive.

A fiscal spend that does not take place is not then a fiscal spend?

The £20bn you estimate is not provided free to immigrants, they pay for their accommodation and so it does not ‘have to be found’.

If you were correct then Sir Nickells’ conclusion would not stand, but most do economists accept that the surprising thing about immigration seems to be how little it affects unemployment or the per capita income of incumbents. For example, as with David Card’s research and that of NIESR.

A major benefit ignored here is the OBR’s estimate of significant government debt ratio reduction to 2060 as total GDP grows even if per capita stays broadly the same.

Query on Ross: If GDP per capita remains constant, what is the point of any immigration? If doesn’t benefit the incumbents, and the incumbents are so strongly opposed to it, why have any at all since it only allows benefits the elite? I thought income inequality was thought to be a serious problem, if not THE problem?

Any estimate on debt ratio reduction to 2060 would seem likely to be purely speculative, and based on the ONS projection of a UK population of over 100 million by 2114. It’s hard to imagine what that would look like – hardly a “green and pleasant” land – with the majority of any benefits that accrue disappearing offshore.

Roger: Immigration greatly benefits immigrants at no cost to incumbents- surly that matters? But I accept that immigration is a social issue even if it is not an economic one.

The OBR forecast is out to 2060 ie. not that speculative for the foreseeable future

Great article, I’ve been thinking about this subject all day today, especially that the new EU referendum has just been announced for 23rd of June.

I’m an immigrant from Eastern Europe, and I’m proud that I came to the UK and serve this nation with my skills and talent. However, whoever says that immigrants are damaging the economy or that are pulling down wages, I must say they are fairly stupid (sorry). I’m a highly skilled automotive paint sprayer, and I earn just over 40K a year (yes, that’s £20/hour).

Now £40K for a paint sprayer is a colossal sum, even for a native worker, the average paint sprayer earns around £25K-£28K a year. So I’m obviously not pulling down wages, but the opposite: I’m motivating other people to work harder and earn more. The matter of fact here is that I, just like hundreds of thousands of other highly skilled immigrants, am not providing value to the nation by offering cheap labour, but instead, by offering talent, ambition, motivation, unique skills and extremely fast work. Something that hundreds of companies wouldn’t get, if it wasn’t for us.

And we also spend a lot of money and pour it back into the economy to “make the engine turn” – me and my wife are injecting more than £2.7K every month back into the system (well, we are humans as well we go to the pub, we go to restaurants, we eat fish and chips, we drive our car, we pay our rent and bills, etc.), plus we pay hundreds of pounds of taxes, and we never ever claimed benefits.

Just look at the US: it accepted millions of immigrants that literally built the country from scratch, and they are still accepting immigrants that are driving innovation and creating companies over companies, and using their talent to boost the economy and the country is booming with companies that can compete on a global scale because they have access to great talent and great people.

I’m telling you my friends, a country that would close the door to immigrants, will also close the door to innovation, unique talent, and would be a lot less competitive on the global market. Hopefully, the UK won’t be that country 🙂

All the best,

Fery

I agree with your comment, I’m a native but understand and agree that many skilled hard working people bring innovation and creative progression as a nation. Unfortunately there is a balance on both ends of hard working. One may work hard to gain at others expense then you have hard workers who work hard for a better future for everyone.

I agree with you , one part of immigrants help boost UK’s economy,they are hard working and pay tax,but there are other part of immigrants who came to UK to claim benefits.

Overall, looking at GDP growth for last 50 years, immigration demonstrably has no effect on economic growth.

well detailed report, in 1999 to 2009 immigrants have done significant contribution to increase the economy of the eastern part of England. those immigrants were students from Africa, offered cheap skilled and non skilled labor to numbers of high tech industries in east England,also pay school fees, taxes , spend a lot of money in restaurant, supermarket, shopping mall and majority of the never ever claimed benefits,it is not true that majority of migrants claimed more benefit than paying taxes as spelled out by Prof Christian Dustman

I am interested in having a copy of Professor Christian Dustman’s report supporting his assertion that majority of immigrants claim more benefit than paying taxes.

Productivity in the UK has barely grown since the late 90s because of underinvestment in industry.

Capital has been routed to infrastructure to support a larger population: roads, hospitals, schools in particular.

Historical investments in infrastructure, both public and private, after allowing for depreciation/obsolescence represent over £1million/head.

Only looking at income, benefits, and tax contributions misses the balance sheet impact of too fast growth.

Once productivity/head falls too far behind the UK’s competitors in high-tech industries it will be very hard to attract future investment in order to catch-up

What I find more interesting is that the Remain Campaign seemed to provide solid statistical analysis as to how immigration improves the UK economy where the Leave campaign have barraged comments about without any backup, clearly targeting those who either do not wish to view the facts or do not have the basic skills to understand them.

This is not the only website which has positive analysis for immigration and we are not the only country to prove the benefits of it.

The Leave immigration agenda was a clear scapegoating mechanism designed to do one thing – get the uneducated and xenophobes to vote leave. Farage has been using this as the basis of his campaign since the beginning of his leadership within UKIP.

Statistics also show that it is UK natives that are the cause of NHS waiting lists (the young and elderly). The fact that we have a shortage of nurses and doctors that these posts are being filled by immigrants speed that some of them are valuable to our economy and struggling health system

Nice report. It will be interesting to see how attractive the labor market remains and impacts the longer term migration trends once the dust settles from brexit. Migration for education will likely remain strong, but the trend for where these graduates will move for work is more open for change.

Speaking of “lump of labor”, it would be more informative to have the break-downs by industries, occupations, skill levels within those (not all nuclear physicists are equally skilled, not all janitors are equally skilled, not all computer software developers are equally skilled, not all police detectives are equally skilled…), education levels (years completed?) academic performance…

Of course, collecting such detailed statistics would not be quick, cheap, nor easy.

I study immigration as a process, types of immigration and opportunities in different countries of Europe. Thanks for the helpful article.

Good work thanks for sharing

thank you for all your efforts in editing the articles.