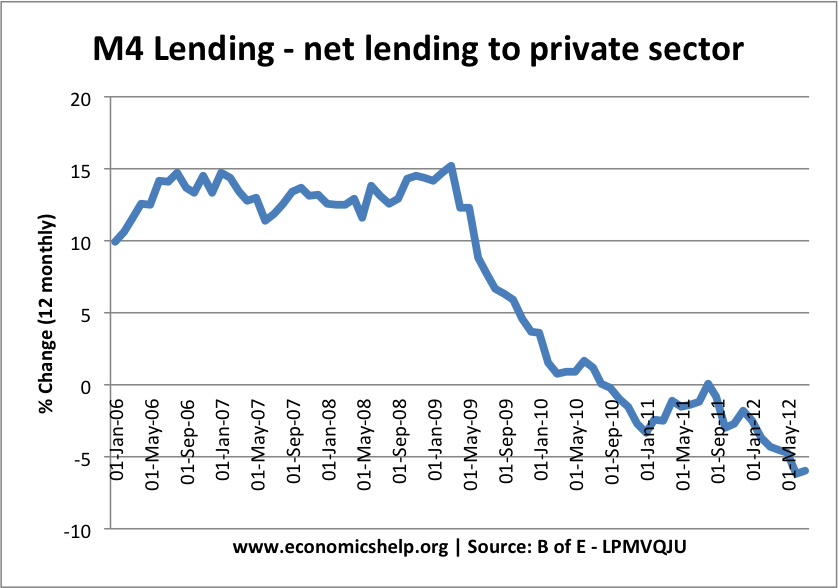

In a previous post, we saw how bank lending in the UK fell during the credit crunch, contributing to the length and depth of the recession. Because of this the Bank of England and Government have sought to try and increase bank lending – in order to help stimulate economic growth.

Fall in bank lending.

These are some of the different policies that have been tried.

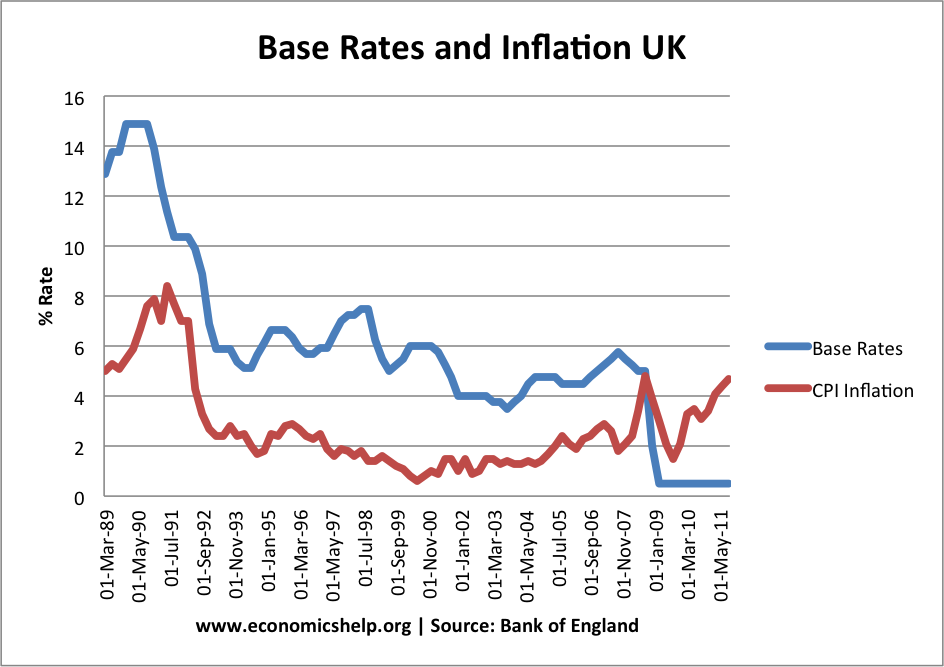

1. Cutting Interest Rates

In March 2009, the Bank of England cut interest rates to 0.5%. Lower interest rates makes borrowing cheaper. This should increase the demand for bank lending as firms and consumers are more willing to borrow rather than save. In normal circumstances, a cut in interest rates probably would increase bank lending.

However, in the credit crunch, lower interest rates were ineffective in increasing bank lending. Lower interest rates didn’t increase bank lending because:

- Although people may have wanted to borrow at low interest rates, banks didn’t want to lend. Banks were worried about the state of their balance sheets; they needed more liquidity. Because of the recession, they were also worried about making loans to firms who might not make a profit on the investment.

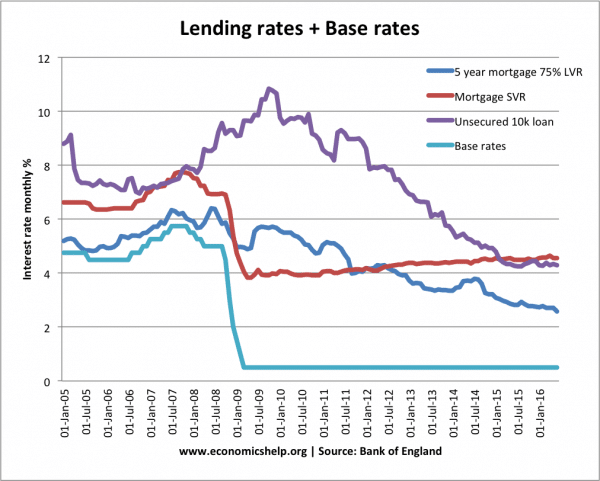

- Also, the cut in base rates were not always matched by a cut in the commercial interest rate charged by banks.

In other words, lower interest rates may increase demand, but they do not affect the supply.

2. Quantitative Easing

Quantitative easing is a general policy to try and increase the money supply and indirectly increase bank lending. The Bank of England created money electronically and used this money to buy securities, such as government bonds. They bought bonds from commercial banks. It was hoped that this policy of quantitative easing would:

- Increase the liquidity of banks (banks receive cash for the bonds). It was hoped this increase in liquidity banks had would encourage them to lend to the private sector.

- Lower interest rates on bonds, encouraging banks to lend. By buying bonds, interest rates on bonds go down – making other sources of investment more attractive.

However, quantitative easing was only a partial success. Despite £375bn of asset purchase by the Central Bank, bank lending didn’t increase like it was hoped. This was because banks preferred to hold onto their increased cash reserves and they tried to improve their bank balances. Because of the recession, banks were still reluctant to lend.

- More on quantitative easing

3. Funding for Lending Scheme (FLS)

The funding for lending scheme was launched in July 2012 to try and encourage banks to lend directly to the real economy (household consumers and firms). FLS works by

- Bank of England lends commercial banks funds at interest rates lower than market rates for an extended period.

- If commercial banks expand their lending, they get lower interest rates. However, if they reduce their lending, they have to pay higher interest rates.

- Because commercial banks find it cheaper and easier to borrow – this encourages them to lend to firms and consumers higher quantities and at lower interest rates.

Unlike quantitative easing, FLS is directly tied to banks lending. There is a new cheaper source of bank lending, and in theory this should help increase bank lending to firms and consumers. (More on FLS at Bank of England)

How Effective will FLS be?

- Demand and supply for bank lending will depend on other factors. The Bank of England cannot force commercial banks to lend. If they are risk averse due to the recession, they may not want to take advantage of the cheaper source of finance from the Bank of England.

- It depends on other factors affecting the cost of bank finance. For example, if there is a deterioration in the Eurozone crisis, the cost of bank lending from other sources will increase – offsetting the cheaper cost from the Bank of England.

- Like any policy, it is hard to say what would have happened, if it wasn’t introduced. For example, without Q.E. the UK recession may have been much worse.

4. Nationalisation and government control

In theory, the government have control over some of the major UK banks, effectively nationalised during the credit crunch. At the moment, the UK government take a hands off approach – preferring to let the nationalised banks manage themselves. However, the government could set strict targets for bank lending and take a much more interventionist approach.

There is a reluctance to pursue this policy, because of fear over ‘government failure’. The idea that government agencies may make poor decisions about lending to the wrong people, even lending too much – causing another lending boom and bust.

Politicians often speak about the need for these banks to lend more.

5. Relaxing Rules about liquidity and capital requirements.

Governments often set limits on the amount of capital banks must keep. This is to try and avoid banks becoming illiquid and running out of cash (such as happened in the credit crunch). However, requirements to keep 10% of assets in liquid capital can reduce the amount of funding they undertake. Recently, the FSA have reduced the capital ratios that banks must keep. To fulfil the Basel requirements on liquidity only sovereigns and cash were acceptable, but now banks can fill up to 10 per cent of the required buffer with anything the B of E has agreed to accept as collateral.

Basically, this means it’s easier to keep 10% in capital reserves, and therefore making it easier for banks to lend.

However, there is a danger that relaxing rules on liquidity means banks will become vulnerable to a future boom and bust in bank lending. Also, reducing liquidity requirements doesn’t change many other factors, such as the desire to improve bank balances.

6. National Loan Guarantee Scheme

In March 2012, the government announced a national loan guarantee scheme. In theory, this should make it easier for small firms to borrow money because the government is willing to underwrite the loans. This should make banks more willing to lend because they have less risk of losing the money.

More on national loan guarantee scheme at HM Treasury

7. Forward Guidance

A commitment by Central Bank to keep base rates low for a considerable time. The hope is that if commercial banks expect short term rates to remain low for a considerable time, this will help reduce long term lending rates. See: Forward guidance

Related

Hi Tejvan. This whole crisis-and-aftermath seems to have started with a sudden urge to delever.

When everyone wants to reduce their debt, efforts to increase bank lending are like spitting into the wind.

Arthurian,

Your phrase “spitting into the wind” is far too polite. I’d have referred to a different sort of liquid emanating from a different orifice.