Readers Question: Would a cap on house prices work?

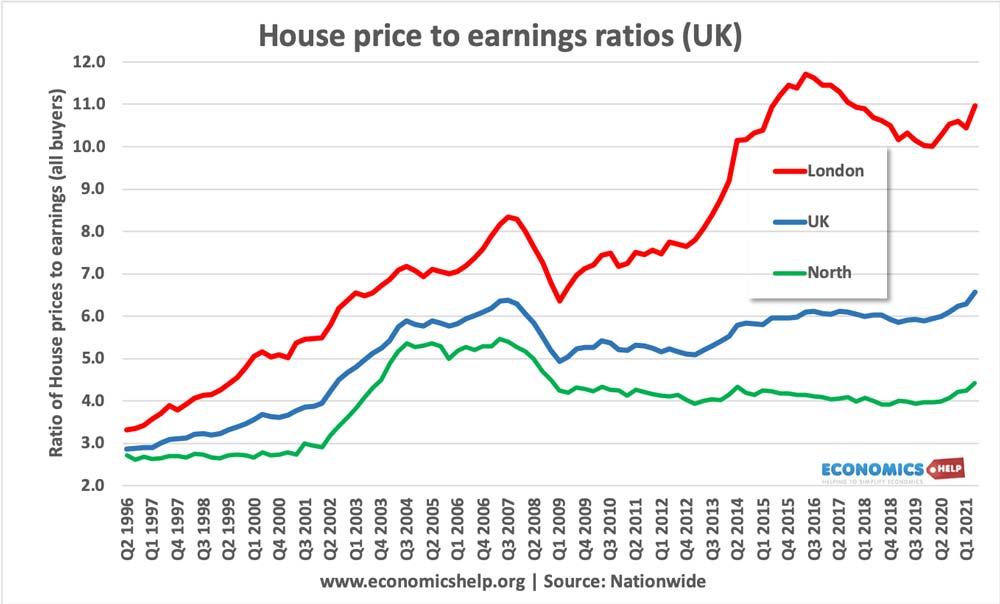

Despite the recession and credit crunch, UK house prices continue to rise. (See: Why are UK house prices so high?) This has caused record levels of house price to income multiples. For homebuyers in London, house prices are approaching a record seven times average earnings. Understandably many feel house prices are already too expensive, and there is a strong case for trying to limit future house price increases.

For example, the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors have suggested that the Bank of England impose a cap of 5% a year on house price growth. (Independent link)

Firstly, how would a house price cap work?

The Bank of England cannot influence supply in the short term. Therefore, they would have to influence demand through credit controls (e.g. limiting amount of mortgages) and possibly interest rates. Both have drawbacks and limitations.

1. Interest Rates

In theory, The Bank of England could use interest rates as a tool to influence house prices. A rise in interest rates, in the current climate, would inevitably cause an end to the house price growth as mortgages would become more expensive. Mortgage payments are a large % of disposable income, therefore any change in interest rates will have a significant impact on reducing housing affordability and housing demand.

However, the use of interest rates to control house prices has significant drawbacks.

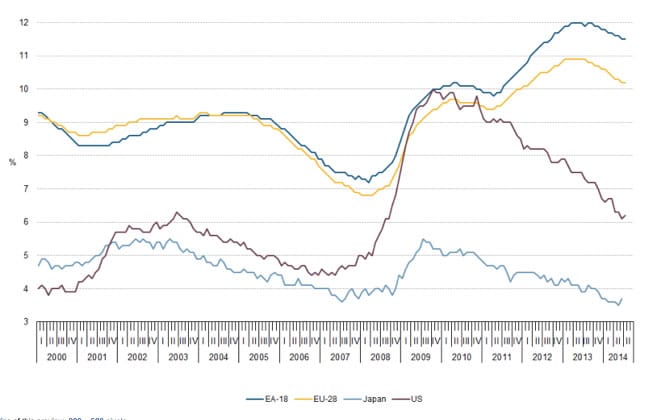

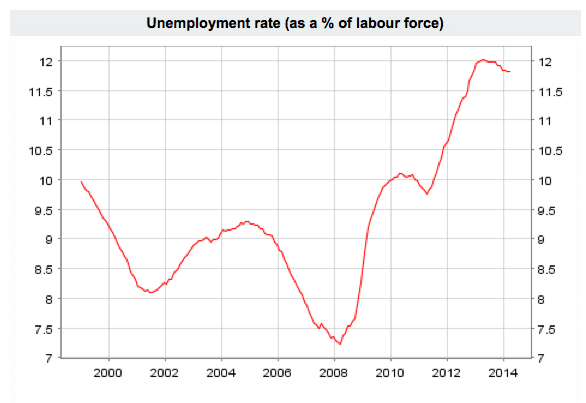

- The main aim of monetary policy is the control of inflation and economic growth. If the Bank is asked to also target house prices, it would mean the Bank of England are placed in a difficult position. To prevent house price rises in London, may require higher interest rates. But, at this stage in the economy cycle, a small increase in interest rates could sniff out the recovery. Interest rates can only achieve so much.

- Time lags. A change in interest rates will take time to feed through into the housing market. Ideally, the Bank of England would anticipate house price changes, but in practise this is difficult to do. Few would have predicted the strong rise in house prices in recent years. If the Bank did increase interest rates to affect demand for houses and mortgages, it could easily get it wrong. By, the time mortgage rates rose, house prices may be falling anyway.

2. Mortgage regulation

A more realistic option is for the Bank of England to adopt new regulation which makes mortgage lending scarcer. If house prices are rising too quickly, the Bank of England could introduce controls which limit the availability of mortgages. This could involve insisting on certain size of deposits or limiting the size of income multiples.