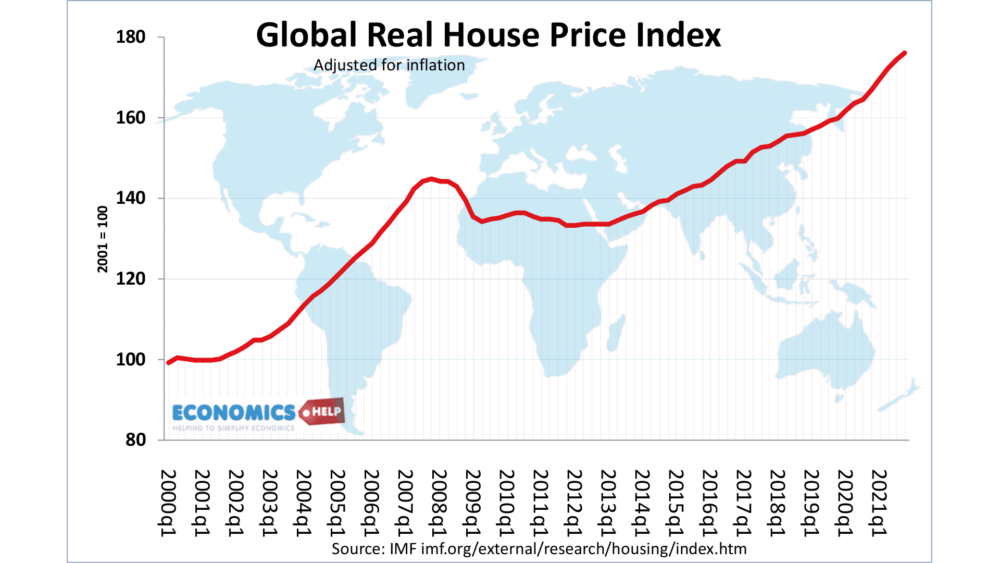

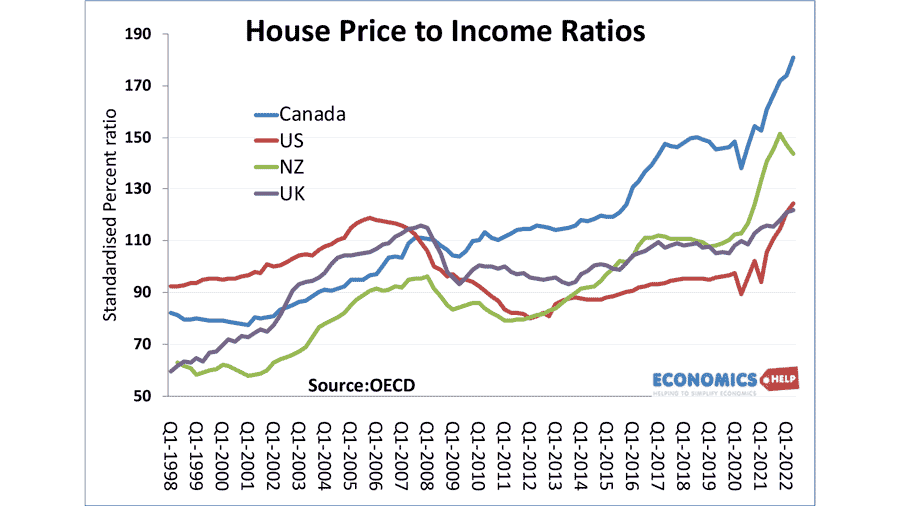

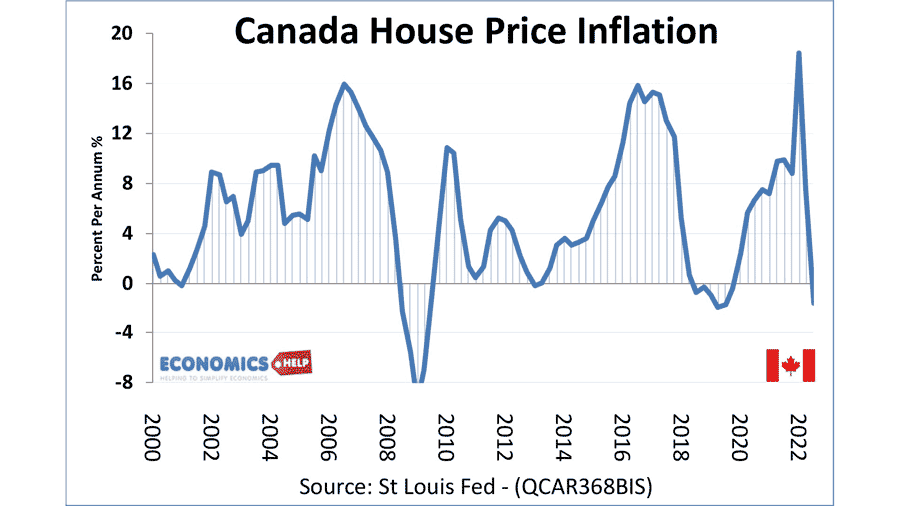

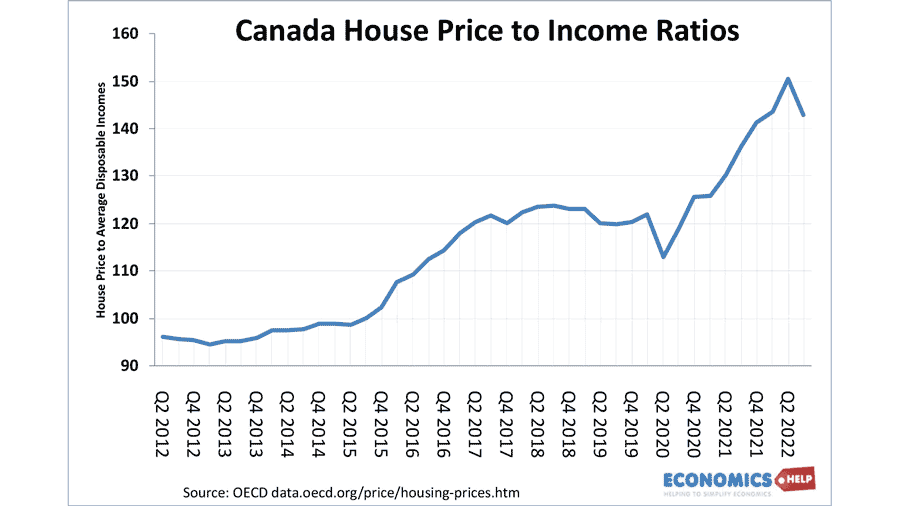

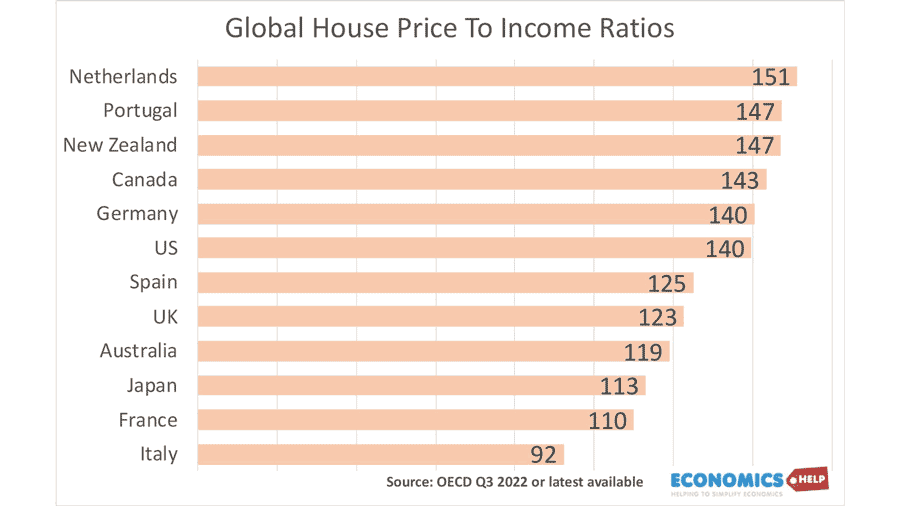

The past couple of years have seen a surge in house prices around the world. This has pushed house price-to-income ratios to record levels – in many cases, outstripping the last boom of 2007.

This is a major warning signal prices are unsustainable and in recent months, prices have started to fall rapidly, with at least 10 countries now entering a period of falling prices.

Countries with the biggest housing booms like Canada, US, UK and New Zealand are now seeing the biggest falls.

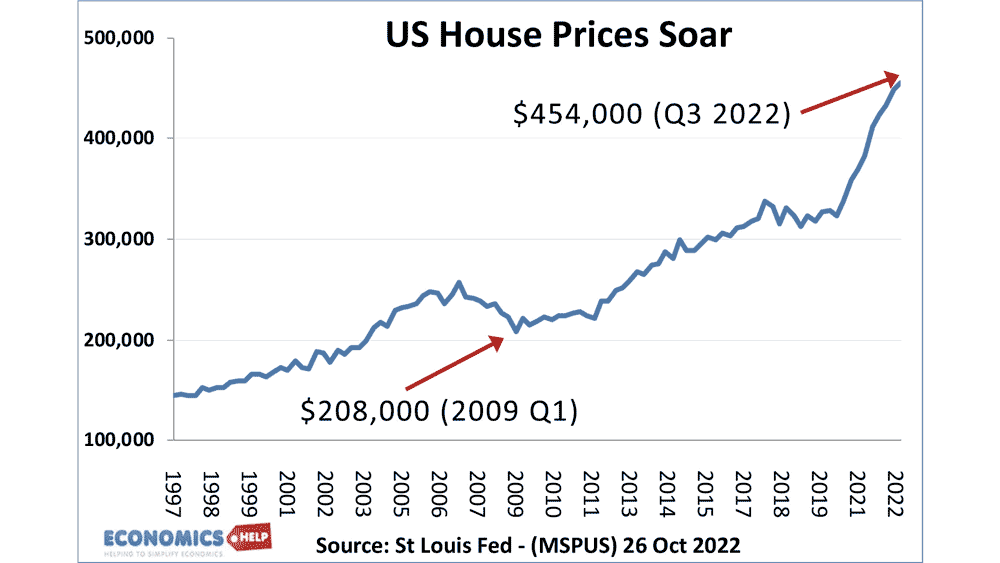

US Housing market

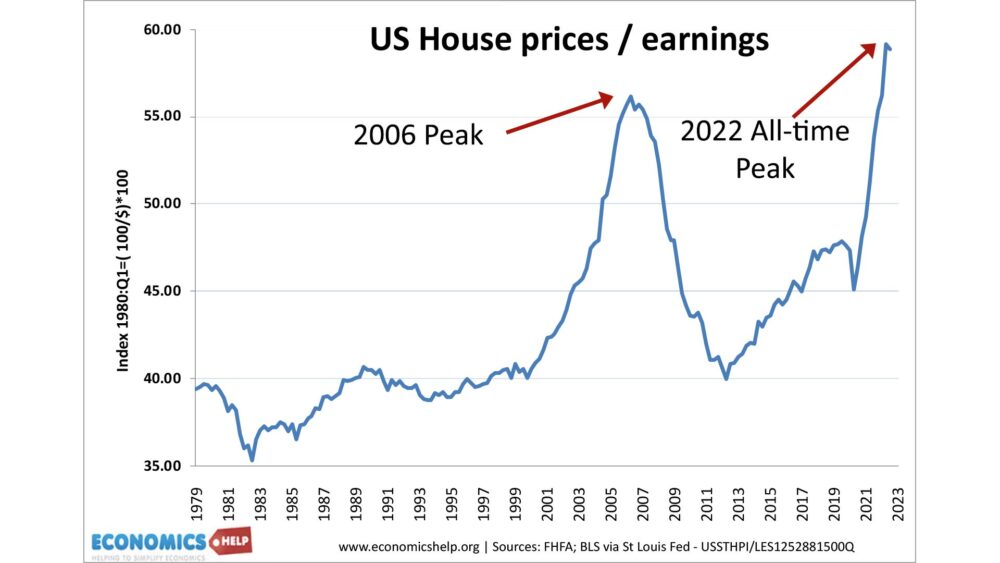

After recovering from the last housing crash in 2008, US house prices have soared, causing a record rise in house price-to-income ratios.

The US market is now more unaffordable than in 2006. It is a similar story in Canada, which has seen one the fastest house price growth in the world.

Yet, both north American countries are now seeing how quickly a housing market can go from boom to bust.

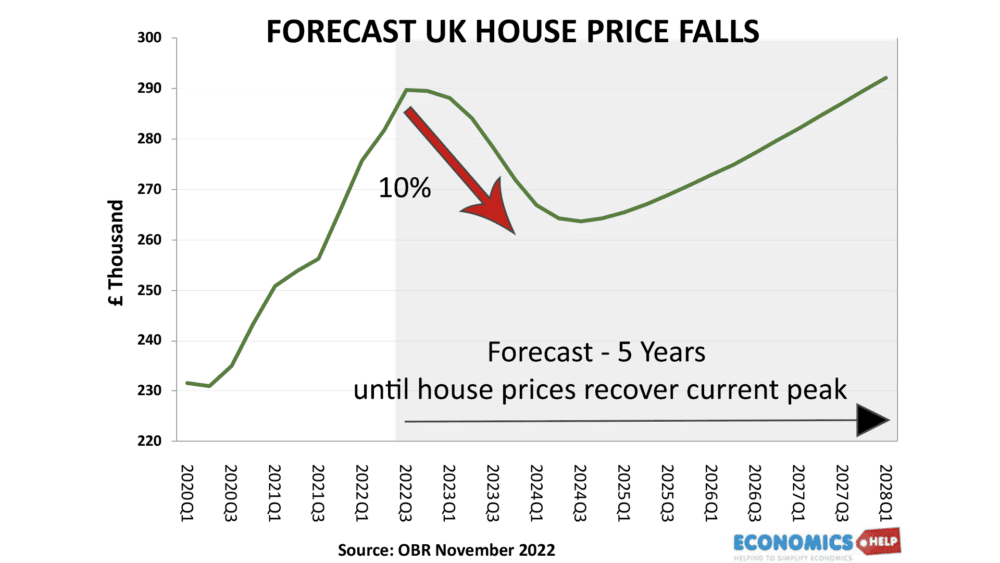

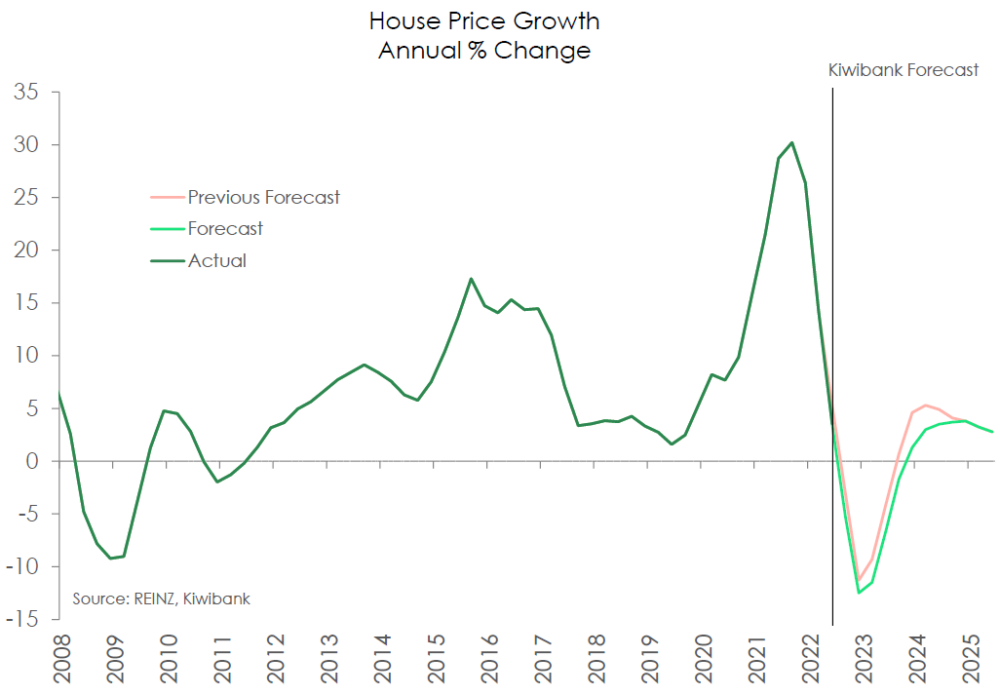

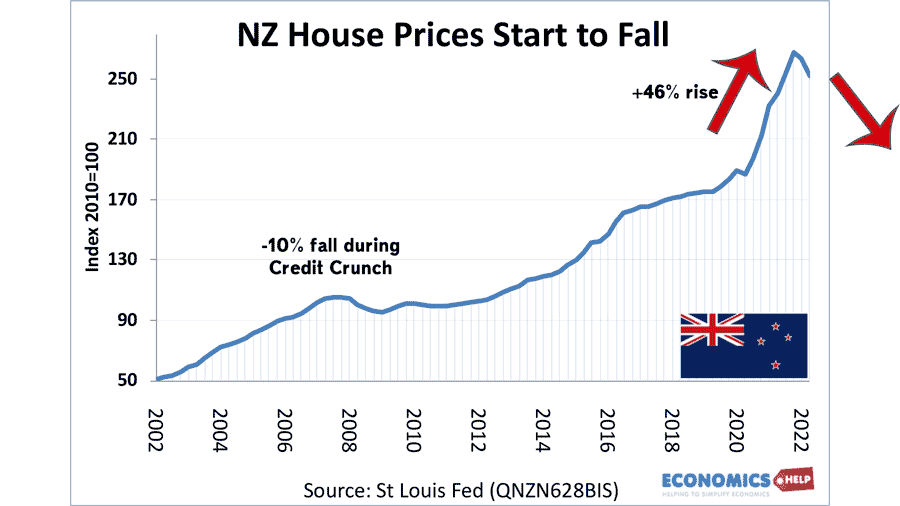

Experts predict prices could fall between 3 and 15% next year in Canada and US, with some saying even these predictions are conservative. In the UK it is a similar story, with some experts predicting in the region of 10%. In New Zealand Goldman Sachs predicted a decline of 20-25% from peak to trough. Experts are often reluctant to predict price falls until they actually see prices falling. No one likes to go out on a limb for fear of being wrong. It is better to be wrong in a crowd than right on your own.

How did we end up in the same cycle – 15 years after the last devastating crash?

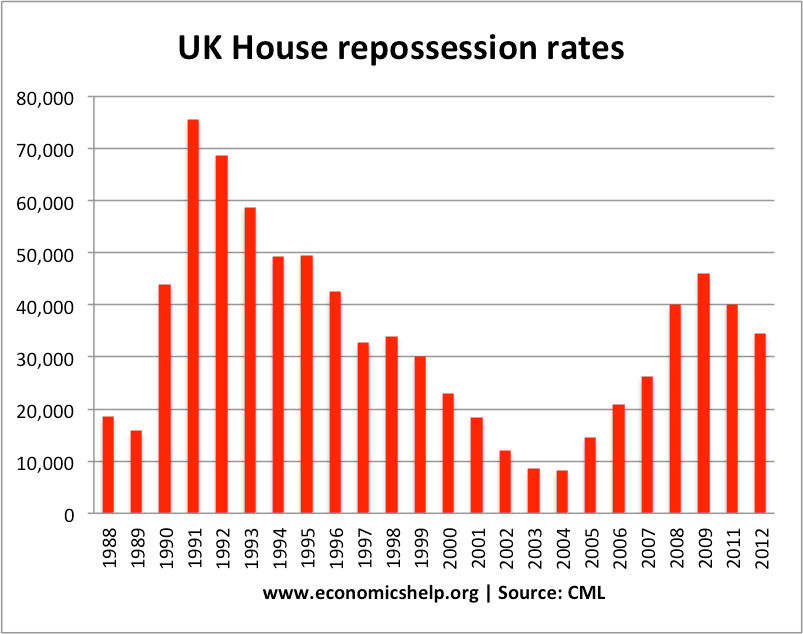

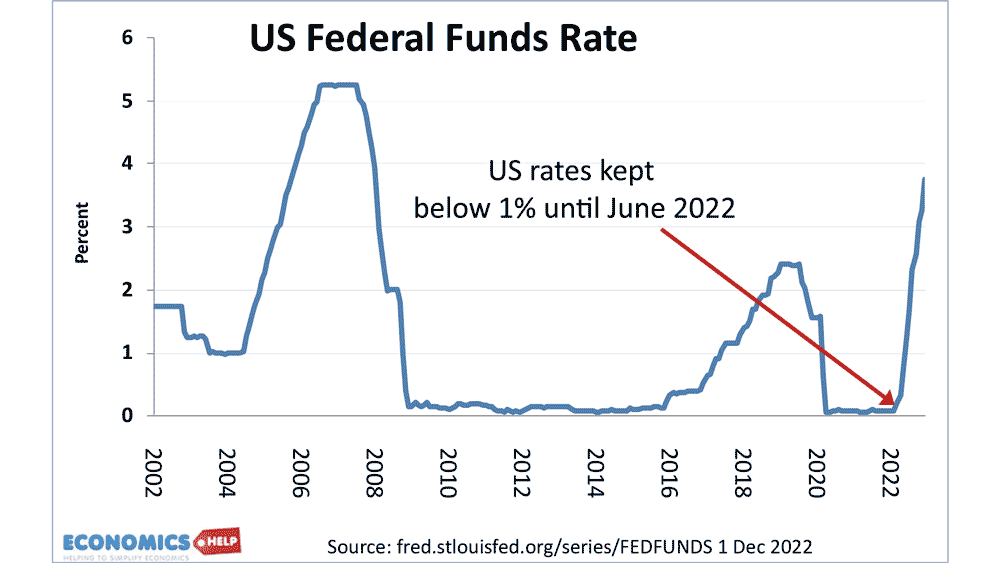

Back in 2006/07, mortgage defaults in the US caused a wave of bank losses, leading to a global credit crunch, deep recession and falling house prices. In response to the depth of this recession, Central Banks around the world cut interest rates close to zero. An unprecedented and radical move.

Now, these ultra low-interest rates and quantitative easing did little to promote a return to strong economic growth. Growth has generally been sluggish, But, by trying to prop up consumer spending, it supercharged housing markets. There was a perfect storm of factors, which pushed up house prices. These factors were very cheap mortgages, poor returns on stocks and bonds and a shortage of supply in many advanced industrial countries. Then in 2020, Covid lockdowns caused an unexpected rise in demand, as people spending more time at home, wanted a better place to live. In the US prices rose 40% in the space to two years, a surge in prices that is reflected across the globe.

Rising interest rates

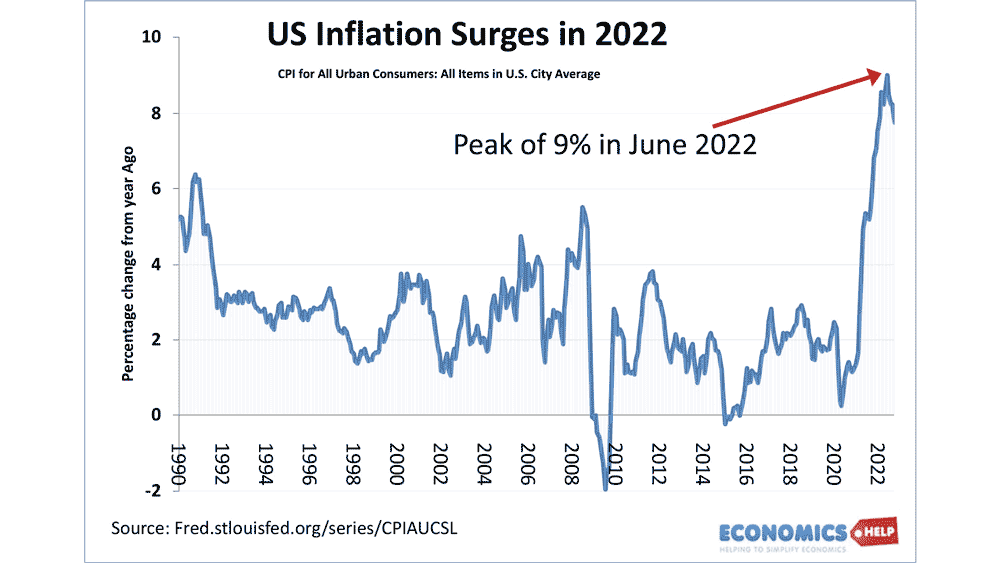

However, this confluence of positive factors suddenly changed in 2022. Unusually high inflation has caused Central Banks to raise interest rates rapidly. For homeowners and investors used to 12 years of very low-interest rates, this is a real shock that changes the dynamics of buying a house.

Suppose a householder could pay $2,000 a month mortgage payment at 3% interest rates – they could get a mortgage for $420,000

With interest rates rising to 7%, they could only borrow $285,000.

Understandably, this sharp rise in interest rates will reduce demand for buying a house. From both first-time buyers and buy to let investors.

In the 2010s, buying a house was one of the best forms of investment. It was cheap to get a mortgage, rentable income was good, and rising house prices all made it attractive for investors to buy. But now, buy-to-let is no longer profitable, with rentable income not being much more than mortgage payments. The main boon for investors has been rising prices, but now prices are forecast to fall it becomes a good time to sell.

Not all countries have been caught out in the 2010s housing boom.

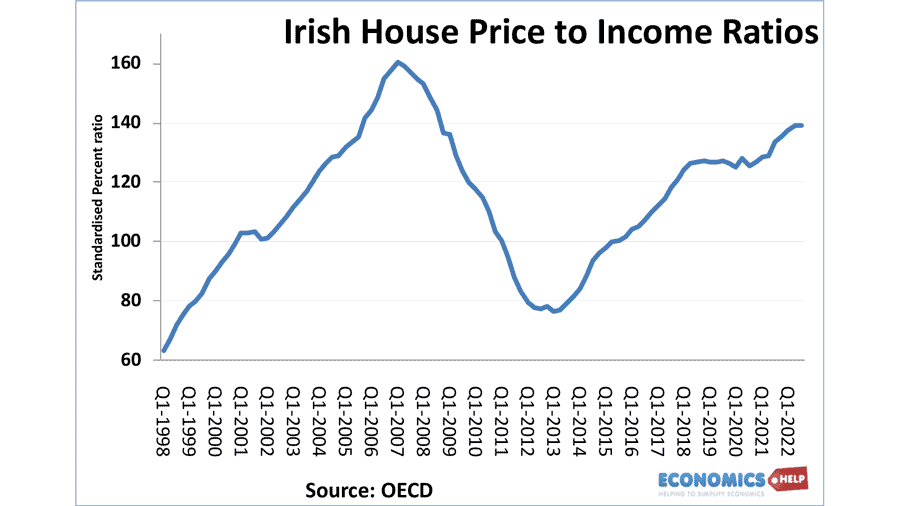

Interestingly, some of those most badly affected by the last housing boom and bust have a more moderated market. Ireland’s price-to-income ratio is still below the last peak. Spain also has moderate household debt to GDP.

Per sq metres, Ireland has one of the cheapest housing in Europe, compared to Czech and Slovakia where it is the most expensive.

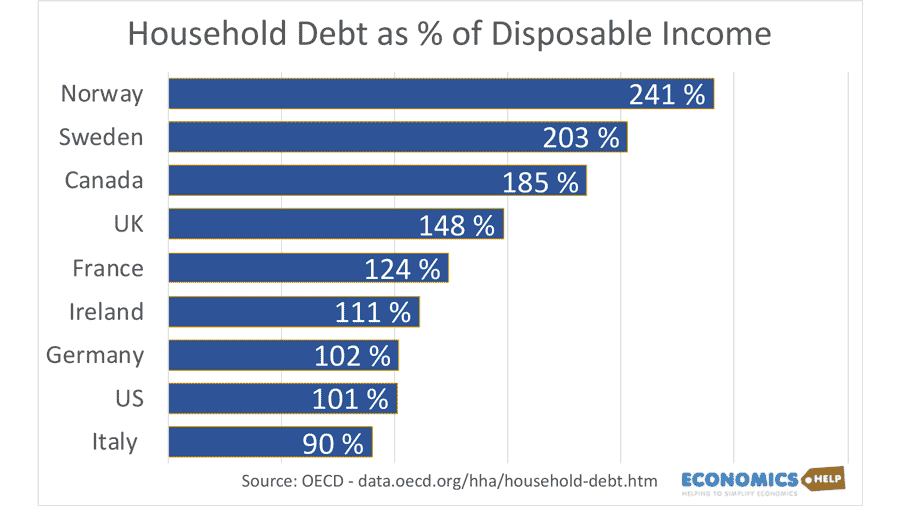

It is ironically Canada, Australia and Nordic – countries who avoided the worst of the last housing bubble, have become more susceptible to this one.

Sweden’s central-bank boss has likened the level of household debt in Sweden to “sitting on top of a volcano”

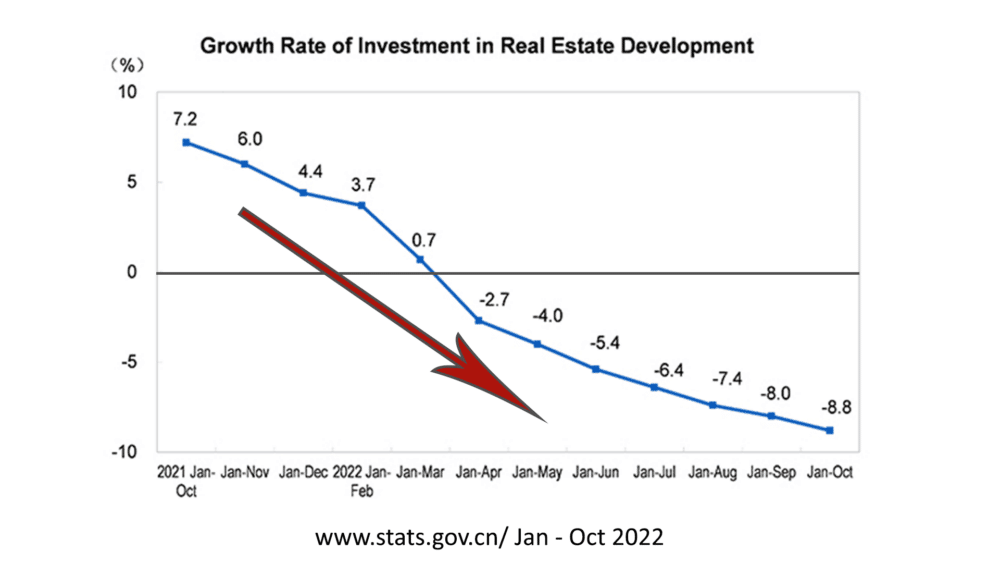

The Chinese bubble

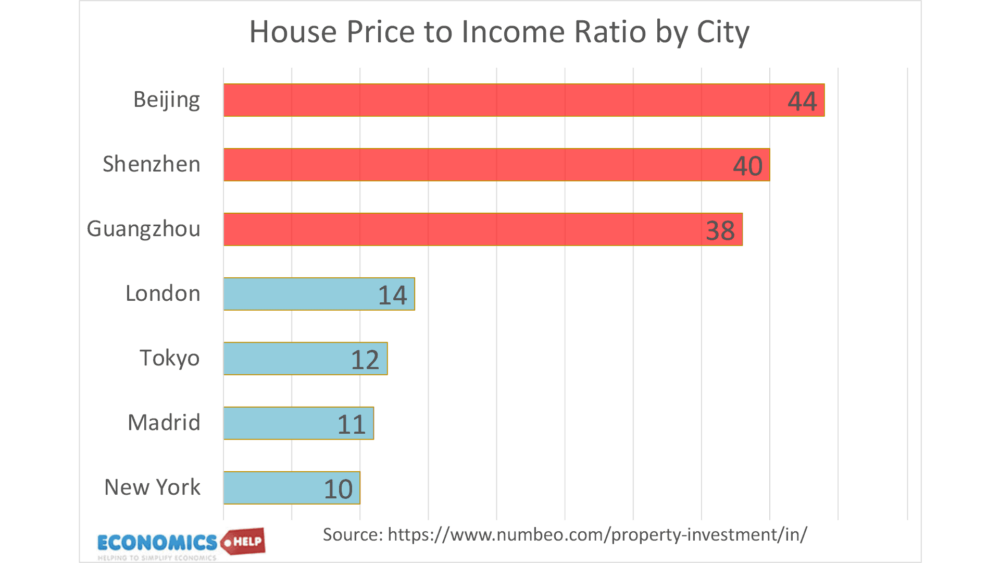

One of the countries most at risk of a property bubble is China. China saw a 378% rise in house prices in the past 16 years. If we think London house price-to-income ratios are absurd at 14 times income, just think of Beijing where it is 44.

The problem in China is different to elsewhere. There was a boom in not just buying but building too. In a bid to raise finance to fund more buildings, property developers sold houses, they haven’t finished buying. Understandably Chinese mortgage payers have got fed up with paying for a house they can’t live in. This caused a mortgage strike and the property market went into crisis with the biggest homebuilder running short of funds.

Combined with covid lockdowns, the Chinese property market is under severe pressure, with demand and prices falling

In some ways, this housing price collapse will not be as devastating as in 2008. There are not as many sub-prime mortgages sold, banks are not as exposed to mortgage defaults, and they have better capital buffers. But, falling prices invariably cause serious economic costs. Falling prices reduce wealth, confidence and therefore willingness to spend. Housing accounts for $250trn of wealth – compared to $90 for stock markets. (Economist.com) Combined with high inflation, consumer confidence has already sunk to low levels. And falling prices will also cause a decline in home building a key sector of economic activity and reduce geographical flexibility

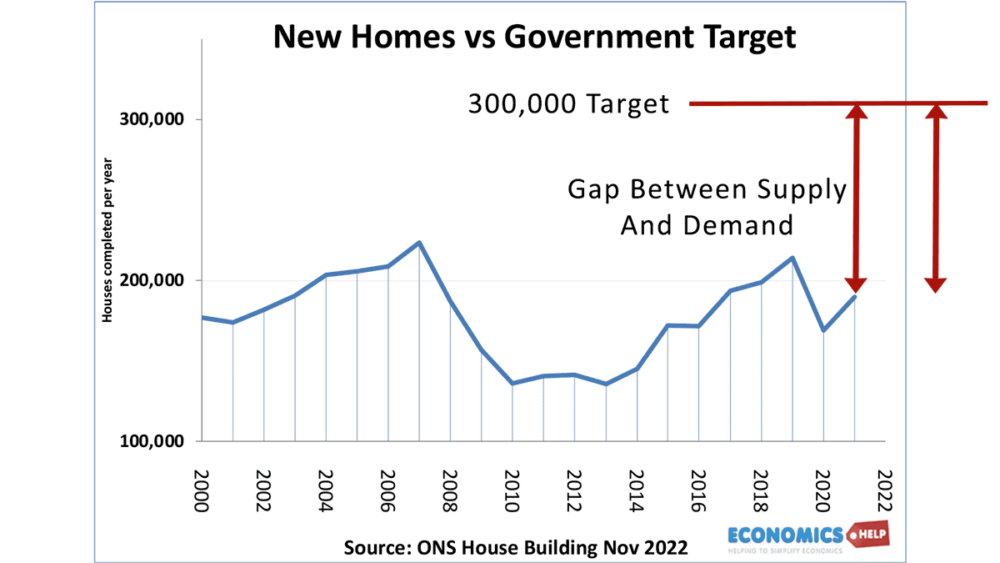

The extent to which prices fall will depend partly on the available supply. For example, the UK has record house price to earnings ratios, but for a considerable time has failed to increase supply in relation to demand. The UK has the lowest housing stocks of any European country, a feature which will limit price falls, and increase very long-term prices. Nevertheless, the OBR still predict 10% fall in 2023.

By contrast, a country like New Zealand has seen a surge in prices, but also growth in housebuilding.

2023 will see a dramatic drop in demand, as higher supply still comes onto the market. This is the recipe for a large fall in prices.

This graph for US housing supply shows how a surplus of housing on the market is growing to put downward pressure on prices. Though not quite as severe as the 2008 crash, it is getting close.

The Final graph shows the most expensive housing markets with the ratio of house prices to disposable income. The Netherlands most expensive, and Canada and New Zealand are not far behind.

Further Reading

- OBR Predict fall in House prices in 2023

- How did we end up with a broken housing market?

- UK Housing Market in 2023

External links

- IMF Global House Price

- OECD Housing Prices

- Global Housing Prices – Economist.com

- A Global Housing Slump is coming – at Economist.com

I would be interested in information on the Scottish housing market.