Readers Question. We hear much about the “pensions time bomb”, as people tend to live longer and there is a bulge as “baby boomers” reach retirement age. We also hear much about the need to save for retirement. Saving *money* may mean people have more money in retirement but surely the real problem is to ensure there is more output; money is worth only what it can buy. Is there a risk that money saving will simply reduce current output and so reduce the income and incentives needed to ensure we have the investment that will enable us to increase output over time?

It is easy to see how it makes sense for an individual to save for retirement but at the national level, it may be counter-productive.

Basically, is there a concern that higher savings for pensions will lead to lower economic output?

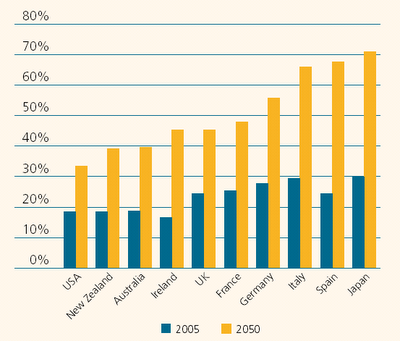

Forecast for Dependency Rates

Source: Dept for work and Pensions

Firstly, western economies do face a pension time bomb. Dependency rates are forecast to rise (though the UK is unlikely to be as badly affected as other countries, such as Spain, Italy and Japan.) An ageing population means state pensions will take up a bigger % of GDP. Higher savings would help with the private sector pension deficit and provide more funds for pensions. But, would higher savings lead to lower growth?

Would an increase in Savings help or hinder the future pension requirements?

A higher saving rate does not have to lead to lower economic growth. In the post-war period, Germany and Japan had a relatively high savings rate compared to the UK, but their economic growth rate was better. Savings can finance not just future pensions, but can also finance present investment. For example, if you save more money in the bank (for your pension) the bank is able to lend more out to firms who wish to increase their capital investment. Therefore, this saving can help improve long-term growth, and also provides a source of income for your future retirement.

In the past, people have often felt economies like the UK and US have neglected savings and focused too much on consumer-led growth. If saving rates are low and consumer spending high, we arguably get an unbalanced economy – often causing a current account deficit as higher spending sucks in more imports.

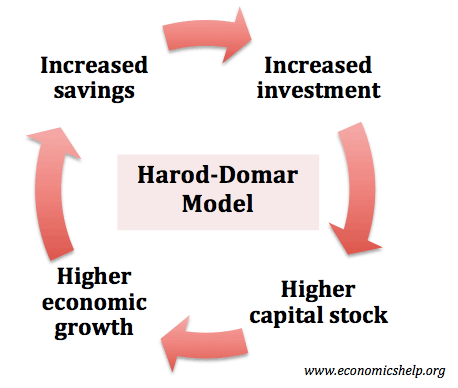

Importance of saving in Harrod-Domar model of growth

Some economic models of economic growth, such as Harrod-Domar model, place a lot of emphasis on increasing saving rates as a means to increase the rate of economic growth

Potential problem of a sharp rise in savings

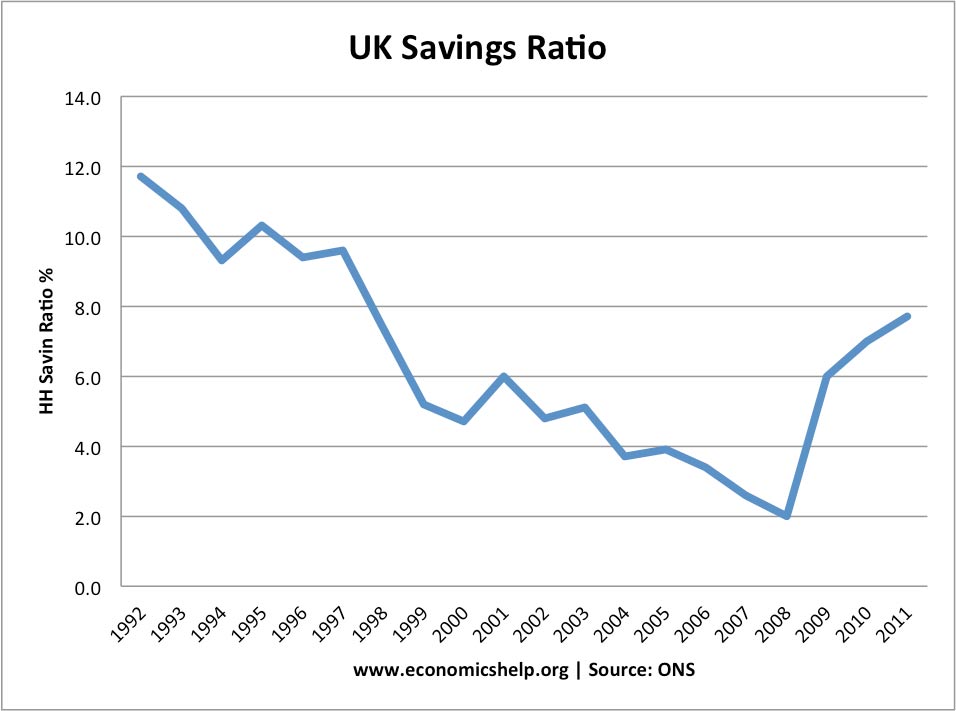

If we look at the recent UK savings ratio, there is a clear trend of running down the savings ratio during the period of economic growth from 1992 to 2007.

In 2008, the recession led to a sharp rise in the savings ratio from 2% to 8%. This rapid rise in savings contributed to the fall in consumer spending and the depth of the recession. From a macroeconomic perspective, a rapid rise in saving can cause a fall in output, which makes everyone worse off.

Interestingly, Keynes described this a ‘paradox of thrift’ – it may make sense to save personally, but if everyone does it at once – it can cause a recession. However, this paradox of thrift is more concerned with the short-run effect of a sharp rise in the savings ratio. If a country has a higher level of savings over the long-term this can still be compatible with higher investment and higher output.

Pensions and Value of Stock Market

The recession and poor performance of the stock market have meant that many private pensions have been downgraded. People’s pensions are worth less because of falling asset prices.

State Pensions and Tax Revenue

The biggest concern over pensions is related to government provision – of not just pensions, but related health care costs. As the population ages, government spending commitments increase. The government does not save to pay state pensions. It is financed from current income. Therefore, the ability to pay state pensions does depend on economic output and tax revenues. If output falls and tax revenues fall, the state pensions will become a much bigger % of the government’s income – and it will become harder to pay.

A higher long-term saving ratio shouldn’t conflict with lower output. Though there is still a balance to be struck. In the short and medium term, the UK needs to increase aggregate demand; an increase in savings may harm this.

Related