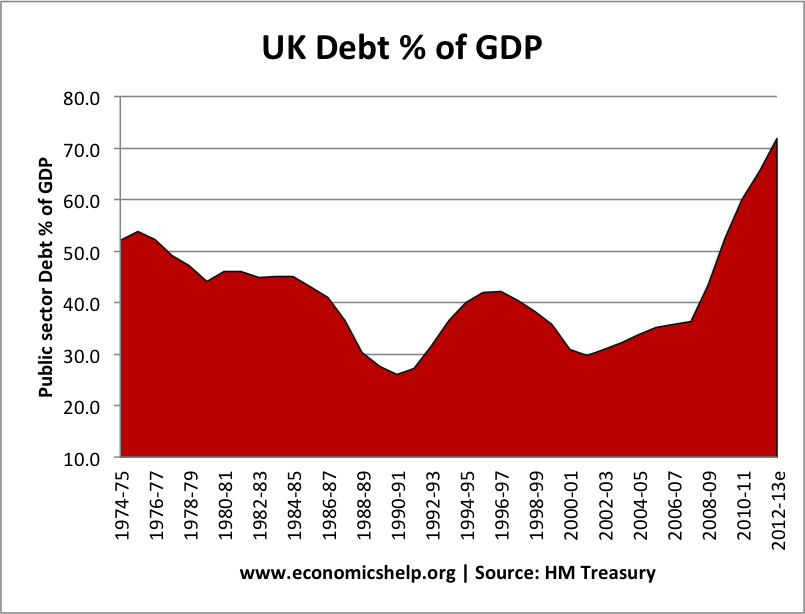

Readers Question: The government keeps claiming that their harsh (but very necessary) austerity policies are working and that they have reduced the national debt by 24%, yet your graphs seem to totally disprove this claim. If anything, your graphs seem to show that the national debt is continuing to rise quite steeply, despite the government’s austerity policies, primarily because tax revenues are down and welfare payments are up because of the rising unemployment across the country (caused as far as I can see by the government’s austerity policies). Is the government painting a misleadingly and unfounded rosy picture to prove their policies are working, or am I failing to read your graphs correctly?

The government is correct to say that the budget deficit (Annual borrowing) has fallen by 25% since the peak of 2009-10.

This means the national debt (total amount government owe) has increased at a slower rate than it might have done. But, it is still increasing rapidly.

(see difference between deficit and debt – if confused)

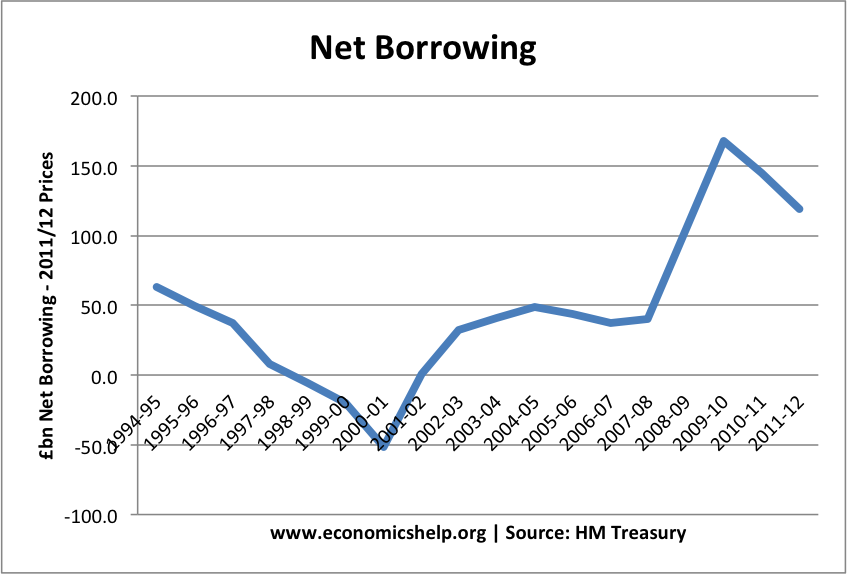

Annual UK Budget Deficit

| 2009-10 | £167.4bn |

| 2010-11 | £145.1bn |

| 2011-12 | £119.3bn |

| 2012-13 | £127.3bn |

Although the annual budget deficit has fallen 25%, the budget deficit is still close to £127bn so national debt (the total amount) has kept rising. For national debt to GDP ratio to fall, we would need an annual budget deficit lower than the increase in real GDP. E.g. if GDP growth was 3% and annual borrowing 2% of GDP, the debt to GDP ratio would fall.

In a previous post, I looked at:

To summarise it was largely achieved by:

- Planned cuts in public sector investment

- The expiration of tax cuts.

- Small cuts in other areas of public spending.

However, what the government didn’t expect or tell us was the extent to which these austerity measures have been responsible for a fall in economic growth – causing the double dip recession.

This double dip recession has also been a major factor in explaining why the deficit has not fallen by as much as the government expected

Recent research has suggested that ill-timed austerity measures will actually increase the national debt – because austerity causes negative growth and a corresponding fall in tax revenues.

In other words, the UK’s austerity measures have had a disappointing impact on reducing budget deficit, but have come at the cost of lower economic growth. This is because they pursued austerity in a deeply depressed economy.

The unfortunate aspect of this is that when borrowing falls less than expected because of austerity policies – many argue what we need is just more austerity! – This is the tragedy being played out in Europe.

Have the Government misled us about Borrowing and Debt?

The government claimed there was an urgent need to cut the deficit. I believe this was incorrect.

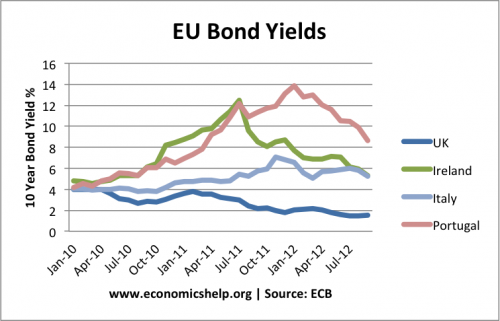

- Since the start of the Euro fiscal crisis in 2010, UK bond yields have fallen; this is because there is strong demand to buy UK government bonds. The UK is not comparable to a country in the Eurozone where markets fear a liquidity crisis. The government repeatedly suggested there was a danger we could end up like Greece or Spain – but I don’t accept that is a good comparison. Outside the Eurozone, the UK has the flexibility to pursue quantitative easing and buy bonds if necessary. It is very different to being in a permanently fixed exchange rate with no independent monetary policy. The UK is not a Greece in the making.

- The government were wrong to claim from 2010. the primary economic objective should be to reduce the budget deficit. Their primary objective should have been to promote a sustained economic recovery and reduce unemployment (and this should still be their objective). If the government had pursued growth; it would have become much easier to reduce the long-term debt burden. By focusing on deficit reduction before the economy has recovered, there has been a big cost in terms of lower growth, and a very disappointing actual fall in borrowing levels.

- The government failed to recognise the time to reduce a deficit is in a boom and not in a recession.

This is not to say debt levels can be completely ignored. The government is partially correct to say the long-term structural debt needed a change of policies. But, there are much less painful measures to reduce long-term structural deficit, than investment cuts which have an immediate impact on reducing spending and consumer confidence. There are alternative ways to tackle long-term spending commitments and structural debt – in a way which doesn’t cause a prolonged recession.

Related

- The biggest lie in UK politics? – Should we worry about debt?