Readers Question: How important is the budget deficit?

The budget deficit is the annual amount the government borrow. The government usually financed the budget deficit by selling bonds to the private sector

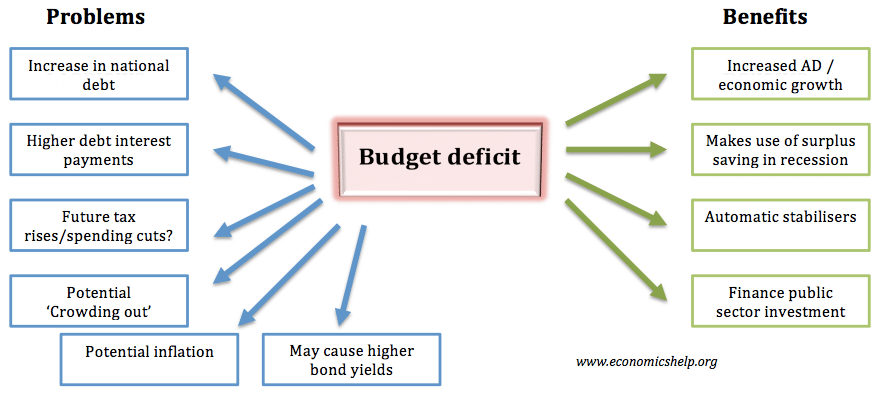

To libertarian and free-market economists, budget deficits are liable to cause significant economic problems – crowding out of the private sector, higher interest rates, future tax rises and even potential for inflation. However, Keynesian economists are more sanguine arguing that in an economic downturn, a budget deficit plays an important role in stabilising economic growth and limiting the rise in unemployment.

Budget deficits have potential economic costs, but it depends on the economic climate, the exchange rate system, interest rates and the reason for government borrowing.

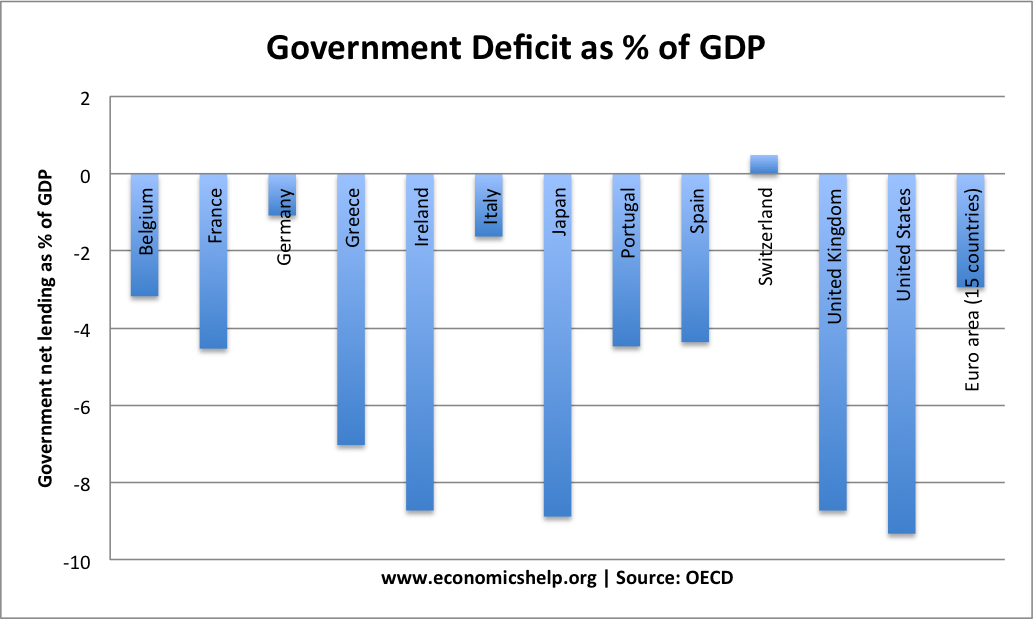

OECD – Budget deficits 2012

The most useful way of measuring the size of the budget deficit is as a % of GDP. The graph below shows that in 2012, there was a large variance in the size of budget deficits. The biggest deficits occurred in Ireland, Japan, UK, and US – with budget deficits of over 8% of GDP.

Potential benefits and costs of a budget deficit

Reasons to be concerned about a budget deficit

- Need to cut spending in the future. Higher deficits are not sustainable forever. Reducing a budget deficit can be problematic. If a country has a deficit that increases too quickly, the government may be forced to adapt policies aimed at a sharp deficit reduction. These ‘austerity measures’ can cause a fall in aggregate demand. For example, during 2012-16, many countries in the Eurozone sought to reduce their budget deficit to comply with EU rules. This deficit reduction caused lower growth, recession and unemployment.

- Increasing national debt. A budget deficit increases the level of public sector debt. Large deficits will cause national debt as a % of GDP to increase.

- Opportunity cost of debt interest payments. A higher deficit will also lead to a higher % of national income being spent on debt interest payments.

- Crowding out. One way of thinking about a budget deficit is that if the government is borrowing from the private sector, the private sector has lower funds to spend and invest. The government is, therefore ‘crowding out’ the private sector – and some economists will argue government spending is liable to be more inefficient than the private sector.

- Potential rise in bond yields. Countries with large deficits may struggle to attract sufficient investors to buy bonds. If this happens, bond yields will rise causing the deficit to be more expensive to finance.

- Potential inflation. There is a fear that budget deficits could be inflationary. For example, if a country like the UK was struggling to attract sufficient investors to buy UK bonds, the Central Bank could effectively print money and buy bonds. However, unless the economy is in a liquidity trap, printing money will cause inflation, and reduce the value of savings, including government bonds. It is worth pointing out, that in developed economies – inflation from printing money resulting from a budget deficit is quite rare.

- Confidence effects. High levels of government borrowing may adversely affect confidence as consumers and firms fear future tax rises or higher interest rates.

Evaluation

There is no simple answer to whether a budget deficit is helpful or harmful because it depends on quite a few factors.

1. It depends on when the deficit occurs. Basic Keynesian analysis suggests that a rise in the budget deficit during a recession is a good thing. In a recession, private sector spending falls and saving rises – leading to unused resources. Government borrowing is a way of utilising these unused savings and ‘kickstarting’ the economy. The deficit spending can help promote higher growth, which will enable higher tax revenues and the deficit will fall over time. If you try to balance the budget in a recession, you can make the recession deeper. Austerity can be self-defeating.

However, if the deficit occurs during a period of strong economic growth, then the government deficit will be crowding out the private sector. Government borrowing will reduce private sector investment and spending, and you could argue that government spending is more inefficient than the private sector. One example is India. In 2012, the Indian economy was growing quickly, but the budget deficit was 5.5% of GDP. In this economic circumstance, India would be advised to be reducing the budget deficit

2. It depends on why you are borrowing. If the government borrowed to invest in improving infrastructure, it might be able to overcome market failure and improve the productive capacity of the economy. The return from public sector investment may be greater than the cost of borrowing, and so in the long-term the economy benefits from government borrowing and investment (like a firm borrowing to invest in a new factory). However, if the government borrows and misspends the money or spends it on transfer payments, there may be a very limited increase in productive capacity.

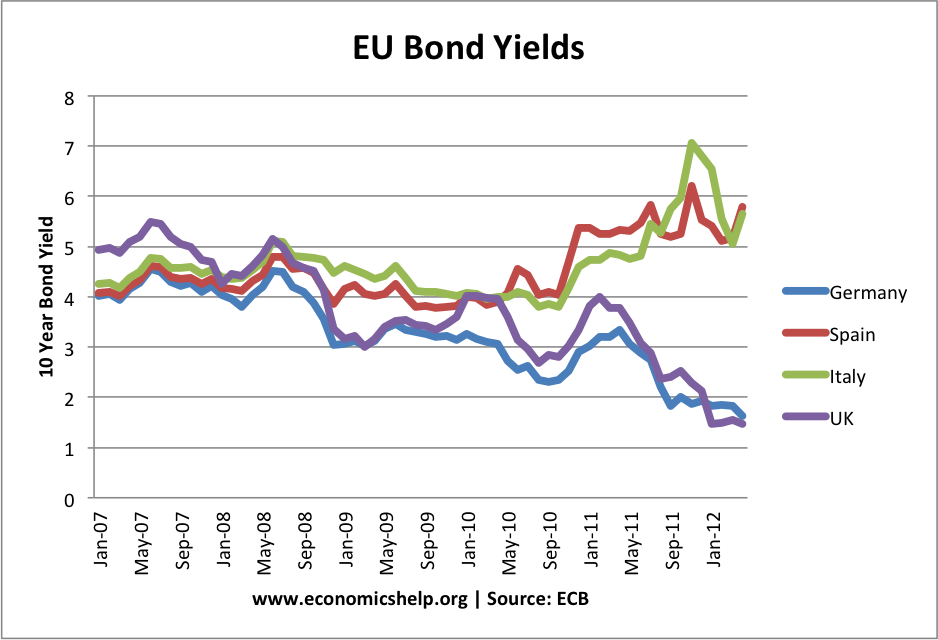

3. It depends on the cost of borrowing

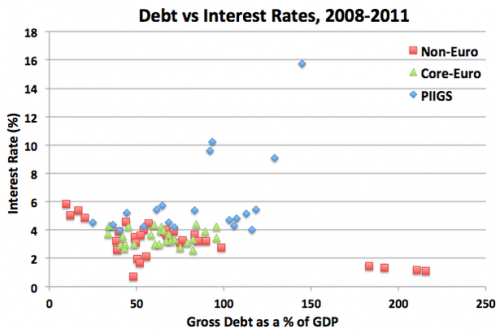

In certain circumstances, the cost of government borrowing falls. In a recession/liquidity trap, the private sector often wants to buy government bonds because they like the ‘security’ of buying safe government assets. This causes a fall in bond yields and makes the cost of borrowing lower. This becomes a better time to borrow money because it’s cheaper and reflects there is high demand for buying government debt. In 2012, countries with large budget deficits – UK, US and Japan – also had very low bond yields, suggesting that the market had strong demand for buying bonds (low bond yields were also helped by the policy of quantitative easing) The fall in government bond yields also shows the private sector don’t want to invest in private sector projects, and therefore in the absence of private sector investment and spending, the government needs to fill in the gap.

In the case of the Eurozone, borrowing has been much more difficult. Bond yields have increased, despite lower budget deficits. This is because it is more difficult to borrow within the framework of a single currency. There is no Central Bank to act as the lender of last resort and there were liquidity fears over the PIIGS countries. This caused bond yields to rise rapidly. Because of the nature of the Eurozone, budget deficits have become more problematic. Eurozone economies have greater pressure to keep low budget deficits. Otherwise, they are more likely to see rising bond yields. If they weren’t in the Euro and had an independent Central Bank, the deficit would be less problematic than it is.

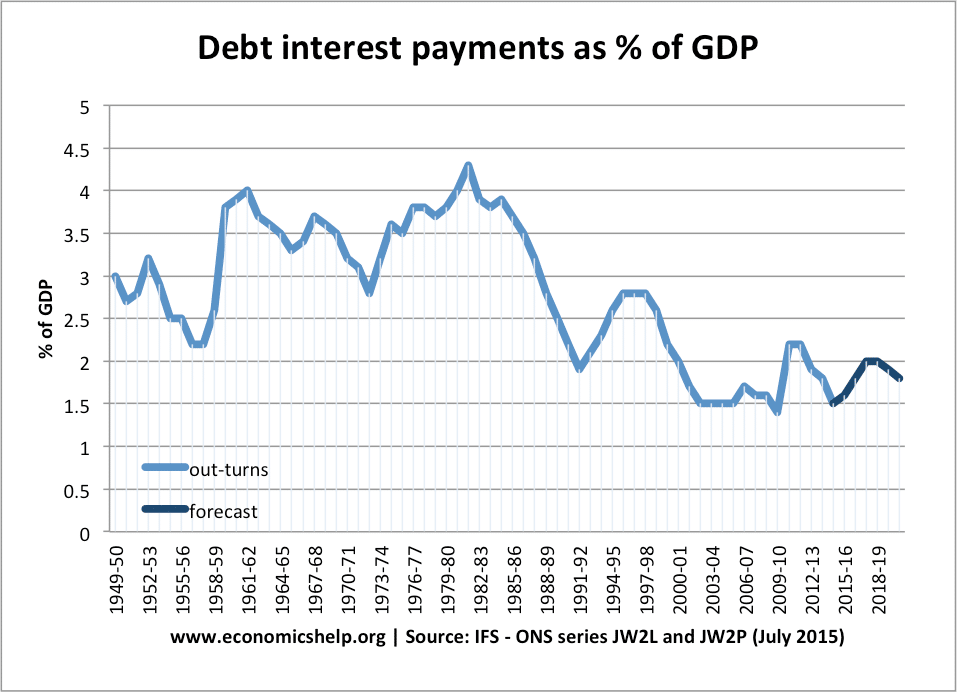

Cost of UK debt interest payments

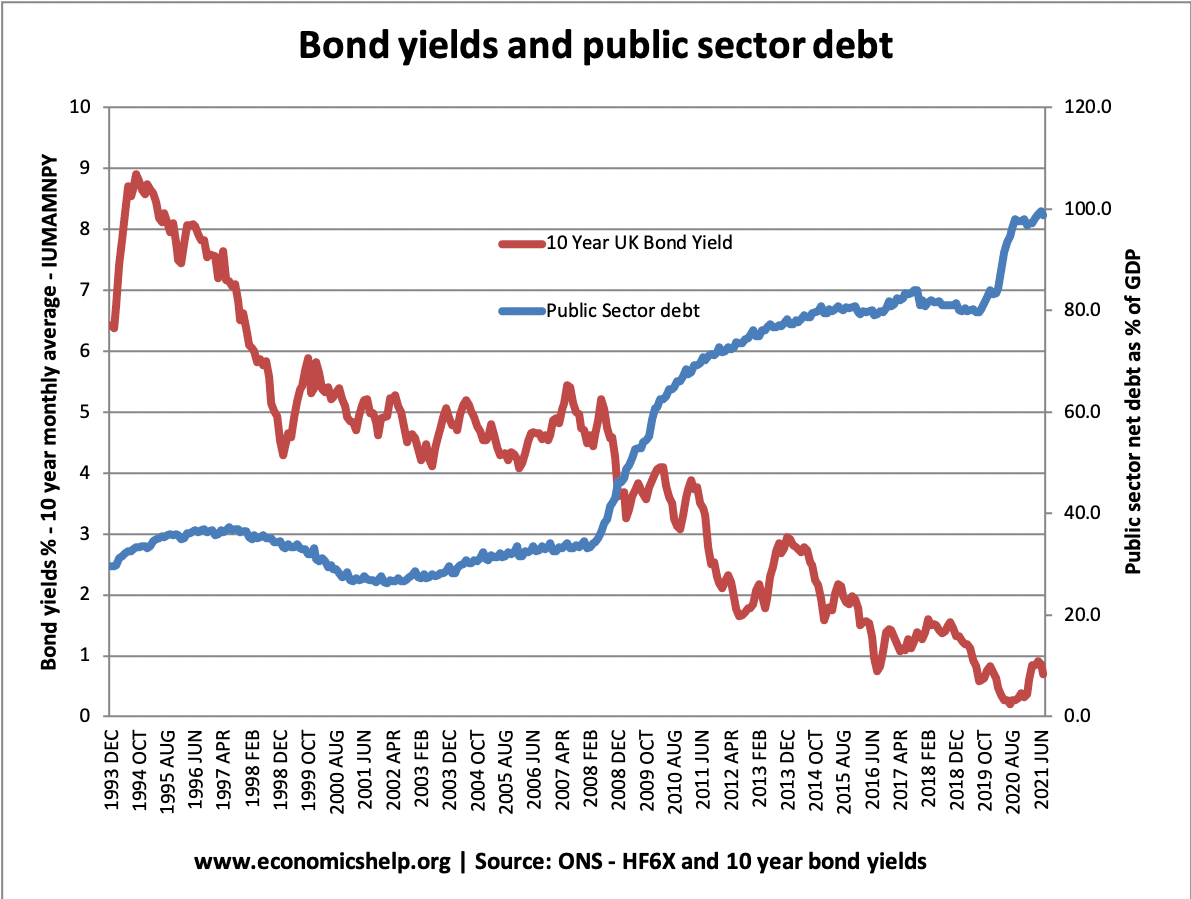

This shows that the very high budget deficit of 2009-10 didn’t cause debt interest payments to be significantly above long-term average.

4. It depends on the future prospects for economic growth

A big issue for the importance of a budget deficit, is what are the economic prospects for the economy? If one economy is predicted to have a stagnating economy, debt to GDP is likely to continue to rise. If another economy is forecast to have strong growth – 2 or 3%, this will automatically cause rising tax revenues and falling government spending on unemployment benefits. Markets will worry about a budget deficit much more, if they feel that the economy is likely to stagnate and unable to grow. Low growth prospects are one of the major concerns over several Eurozone economies.

Conclusion – does the budget deficit matter?

Yes, the budget deficit matters. But, there is no simple answer. It is reasonable to suggest that over the course of the economic cycle, governments should seek to get close to balancing the structural deficit. However, there can be good reasons to run a deficit – at least in the short term. – For example, if the government wishes to fund public investment which offers a decent rate of return. Also in a recession, a budget deficit can play an important role in managing aggregate demand. In a recession, the traditional fears of a budget deficit – inflation, interest rates, crowding out – often just don’t occur. But, government spending financed by borrowing from the private sector can return the economy to full employment quicker.

When does the deficit become too big?

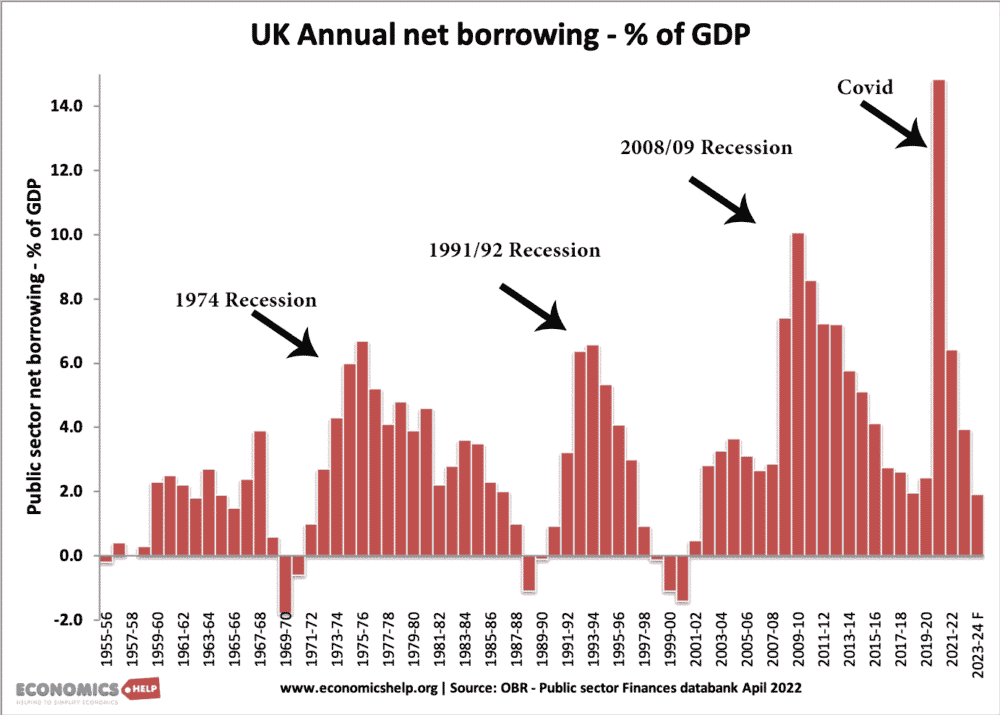

There is no easy answer to this. For example, in 2010-11, the UK deficit was over 11% of GDP – yet interest rates fell in this period. There was no fiscal crisis. Yet in 1976, with lower borrowing, the UK was forced to borrow from the IMF – because the Pound was also coming under pressure.

During the Covid Pandemic, borrowing hit 14.8% of GDP, yet there was no debt crisis.

Higher debt, coincided with falling bond yields.

Related

Learning alot

I learned more about both budget deficit and surplus. Thanks alot

thanks a lot for clear explanation. i just i want to know if the comments given also applies to institutions of higher learning,

Very well noted salient. I still can’t make out much reason for especially developing countries like my own Zambia, which despite having abundant mineral resources, with successive govts boasting of hiring the most competent economic advisers still finds itself over head and ears into unsustainable debt. This is despite having previously fallen out of the trap severally. Lesson well served from this account.