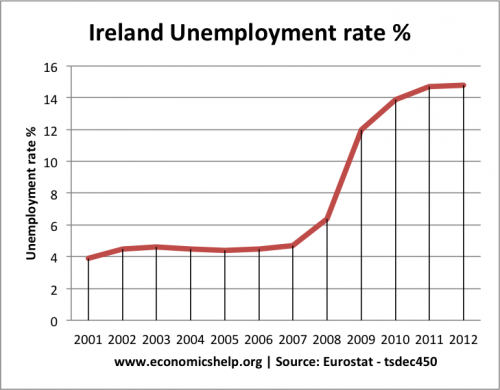

Since the crash, Ireland has recently gained many plaudits in the EU, for sticking to austerity measures, despite the depth of the recession. It is true the Irish have been ‘resilient’ – Large-scale unemployment and lost output have led to surprisingly little social conflict. But, the recovery is very weak relative to the lost output. Unemployment remains very high (12.8%) and it would be higher, were it not for emigration. Since 2008, 400,000 people have left (from a population of 4.5 million) and many of these are graduates. (Ireland’s rebound is European mirage at NYT)

Brief history

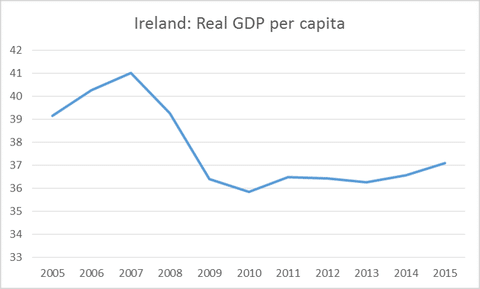

During the period 1995-2007, the Irish economy experienced rapid economic growth. The growth was one of fastest rates in the EU and Ireland became dubbed the ‘Celtic Tiger’. After being one of the poorest European countries in the early 1980s, by 2008, Ireland had become one of the top 10 richest countries in the OECD. During this period, the Irish economy benefited from strong inward investment from foreign multinationals attracted to Ireland by a low corporation tax and pool of skilled labour. Major multinationals, such as Microsoft and Google still operate from Ireland. Ireland also attracted major pharmaceutical firms, such as Pfizer and Glaxo Smith Kline. The presence of major multinationals has meant GNP has been lower than GDP because of the significant transfer payments of company profit back to the original country. GNP is GDP minus net profit transfers.

This period of economic expansion also encouraged a major boom in the construction sector. By 2008, construction accounted for 25% of Irish GDP and 20% of Irish jobs. An estimated 700,000 new homes were built in the last decade of the boom. The construction boom was financed by rapid growth in bank lending. The major Irish banks took on increased risk and increased credit lending on the back of optimism over the continued growth of the Irish economy.

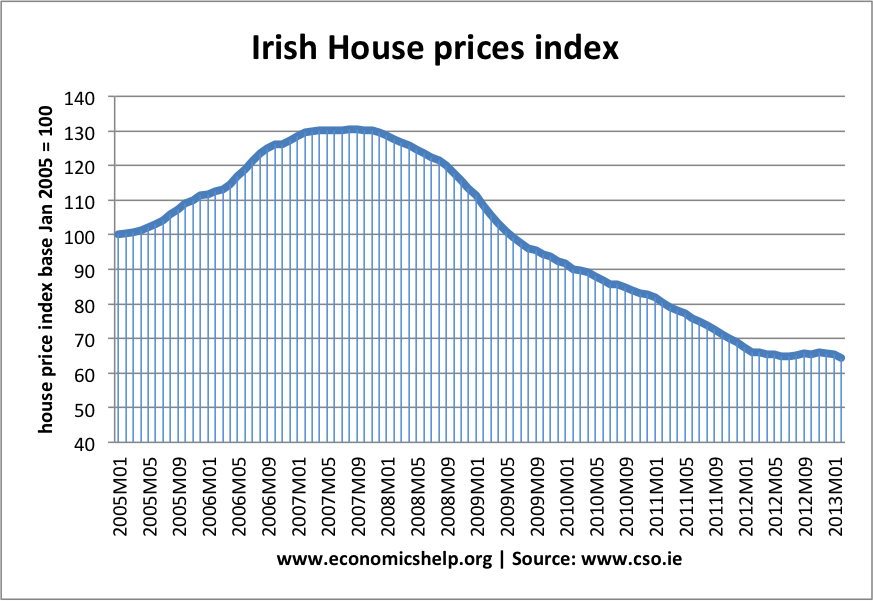

The global credit crunch of 2007/08 hit the Irish economy, housing and finance sector particularly hard. Major Irish banks saw huge losses due to their exposure to sub-prime mortgage defaults in the US. The tightening of credit led to a dramatic change in property prices. After rising over 300% since 1996, Irish property prices fell drastically. More worryingly, the boom in house building has left a vacancy rate of over 15% – meaning prices are likely to be depressed for a considerable time.

Source: CSO

By 2013, property prices in Ireland were over 50% lower than their peak in early 2008. It is one of the biggest property crashes in the world and has had a severe impact on the economy. Falling prices left households with lower wealth, contributing to a fall in consumer spending precipitating the recession of 2008. Economic growth was -1.7% in 2008 and -7.1% in 2009.

More seriously, the property collapse left Irish banks exposed to even greater losses. Repossessions rates rose, but because house prices had fallen, banks lost significant sums. Bank lending to property developers had grown to such an extent, that it equalled the sum of all retail deposits. Combined with losses from the credit crunch, by 2010, major Irish banks faced default.

In 2008, the Irish government agreed to recapitalise the major Irish banks Allied Irish Bank (AIB), Bank of Ireland (BoI) and Anglo Irish Bank. However, by 2010, even this was insufficient, and the Irish government required an IMF-EU bailout to ensure the banks didn’t go bankrupt.

By August 2011 the total funding for the major Irish banks from the ECB and the Irish Central Bank came to about €150 billion.

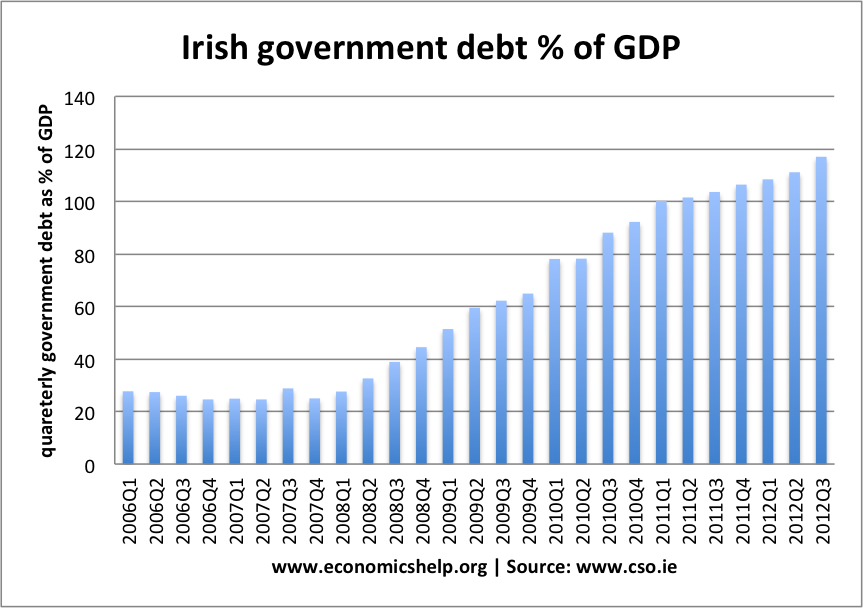

Irish Government debt

Source: cso.ie

At the start of the crisis in 2008, Irish government debt was very low at around 25% of GDP. However, the recession and financial bailout saw a very rapid deterioration in the countries finances.

Firstly, the recession saw a precipitous fall in tax revenue – especially from property taxes which dried up in the recession. Secondly, the government spending on unemployment benefits increased as unemployment rose. Thirdly, in 2010, Irish net borrowing was a record 35% of GDP because of the banking bailout. These factors combined to cause government debt to rise to over 100% of GDP by 2011 Q1. Debt is now nudging towards 120% of GDP.

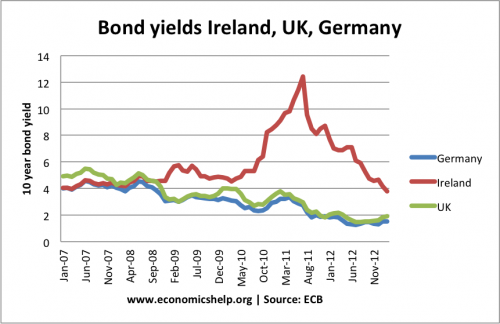

Irish bond yields rose rapidly because markets were concerned about the growth in sovereign debt. But, also, being in the Euro was a disadvantage because Ireland had no Central Bank who could print money to reduce fears over liquidity. With Irish bond yields reaching a dangerously high level of 7%, the government sought a bailout deal with the EU.

Irish austerity package

As part of the government bailout from the EU, Ireland was made to embark on a highly controversial package of austerity measures. The EU argued these austerity measures were necessary to reduce record budget deficits and improve the nation’s finances. Over successive budgets, the governments stuck rigidly to austerity policies, increasing tax rates (e.g. VAT to 22.5%) and implementing spending cuts on both capital and current expenditure. Ireland has been praised, by the EU, for its ability to stick to deficit reduction targets and implement strict austerity measures.

Double dip recession

However, combined with a loss of confidence, the austerity measures played a role in contributing to a double-dip recession. Throughout 2011 and 2012, the Irish economy has struggled to achieve a normal rate of economic growth. In 2012, economic growth was measured at +0.9%, though technically, Ireland went back into recession in the last half of 2012 with very small negative growth in the last two quarters (though this may be revised upwards later) Irish GDP

The austerity packages have been controversial because:

- Many have argued the costs of the financial mistakes and bank bailouts have been unfairly borne by ordinary people who have seen a decline in living standards.

- Economists have argued that in a recession, the austerity measures have been counter-productive because of a large negative multiplier. EU austerity and fiscal multiplier.

- Others are more supportive, arguing that Ireland had no real alternative and is proving a good example of how austerity can work in the long-term.

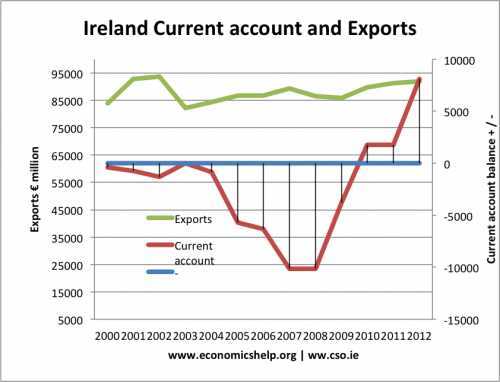

Irish current account

By 2008, the Irish current account deficit reached 5% of GDP. This has moved into a surplus by 2011. However, it has been achieved by lower imports as much as increased exports.

Ireland and the Euro

Since joining the EU, the Irish economy has done very well – helped by EU grants and trade within the EU. This made Ireland eager to join the Euro. Until 2007, the Euro seemed to help the Irish economic boom. However, since 2007, membership of the single currency has created more challenges for Ireland. Unable to devalue, they had to rely on internal devaluation to restore competitiveness and reduce current account deficit.

Without an independent Central Bank, they have seen very high bond yields, putting more pressure on fiscal consolidation at an inappropriate time.

Forecast for Irish economy

There are still reasons to be positive about the Irish economy. The economy is relatively diversified with a strong agricultural and mining sector. Despite its small size, Ireland has many major multinational companies based in Ireland providing the basis of a modern economy. The prolonged decline in real wages has helped restore Irish competitiveness and should see rising domestic demand in due course.

However, others are more pessimistic. The unemployment rate of over 14% is a signal failure and represents wasted resources and lost potential output. The unemployment crisis has seen a reversal of the recent population growth as migration has slowed and the unemployed look for jobs outside of Europe. Furthermore, the continued austerity measures have significantly weakened demand, meaning normal economic growth is failing to materialise. Furthermore, membership of the Euro has left Ireland is in a straight-jacket with little room for fiscal or monetary freedom to pursue economic growth and lower unemployment. The limitations of Euro membership mean that Ireland could face future deflationary pressures – even when current crisis is over. Also, the debt overhang from the financial and property collapse could take several years to overcome, with some predicting property prices will continue to fall another 20%.

Related