Back in February 2007, I wrote an essay – Evaluate the effectiveness of the MPC in controlling inflation.

The last line was:

MPC have done a good job so far. However the real test may come when there is a rise in structural inflation or global instability.

Given the knowledge of the past five years, how should we update this post,?

1. Central Banks should target inflation and growth

In 2007, I wrote The MPC are responsible for setting interest rates and determining UK monetary policy. They seek to keep inflation close to the government’s target of CPI 2% +/-1 %

But, we should start by adding the full remit of the MPC. In their Monetary policy framework, the Bank of England state, their full responsibility is to:

The Bank’s monetary policy objective is to deliver price stability – low inflation – and, subject to that, to support the Government’s economic objectives including those for growth and employment.

By contrast, the ECB seem to give less importance to economic growth, and seem primarily concerned with low inflation.

“The primary objective of the ECB’s monetary policy is to maintain price stability. The ECB aims at inflation rates of below, but close to, 2% over the medium term.”

From: ECB Monetary Policy

A valid criticism of the ECB during the economic crisis has been the fact they have placed too much emphasis on targeting low inflation. For example, the ECB increased interest rates in 2011, even though the European economy was entering a double dip recession. The ECB have been unwilling / unable to consider more unorthodox monetary tools to boost economic growth.

From a narrow perspective of keeping inflation close to the target, the ECB have been quite successful. Eurozone inflation is currently 1.7% and is below the target. However, this period has been very disappointing in terms of economic growth. The EU has entered into a double dip recession. If the ECB had given greater importance to economic recovery and willing to tolerate higher short term cost-push inflation, the EU could conceivably have avoided the double dip recession and done more to reduce the record levels of EU unemployment.

- In evaluation, you could argue that even if the ECB had kept interest rates close to zero, that alone may not have been enough to avoid a double dip recession anyway. However, base rates should not be the only tool that Central Banks consider. Also, the fact that the ECB have been so strident in targeting low inflation, does send signals to European business that policy is more likely to be contractionary.

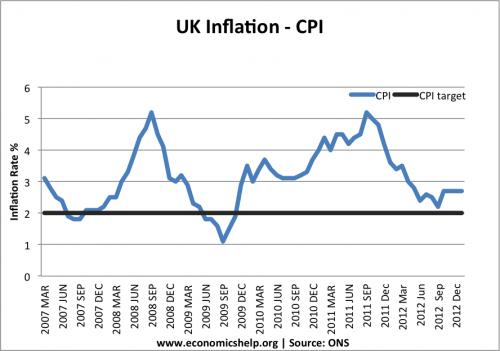

By contrast, the Bank of England has tolerated much higher headline inflation rates.

From the narrow perspective of keeping inflation within target, the Bank of England has frequently missed the target of CPI 2% +/-1. This failure to keep inflation low has also been magnified by the fact that there has been low nominal wage growth. It means that the high inflation rate has led to falling living standards of both those in work, and those on benefits.

However, given the uniquely challenging circumstances of the past five years, it is fair to defend this choice. It made no sense to use interest rates to reduce inflation when the economy was struggling in a prolonged economic stagnation. Firstly this inflation was primarily cost-push. It was due to the effects of devaluation, rising raw material prices and higher taxes. There is also evidence that prices were sticky downwards; the fall in demand didn’t lead to the fall in prices we might have expected.

But, the fact that wage growth was very low, showed there was no underlying demand pull inflation. To religiously keep inflation close to 2%, would have required a potentially very sharp contraction. Given the prolonged recession, you could argue the Bank of England have been too timid in targeting economic recovery. E.g. direct lending to business may have been more successful.

In evaluation, you could argue this might involve the Bank of England extending its original remit, and it would require the government to play a greater role.

2. Limitations of Traditional Monetary Policy

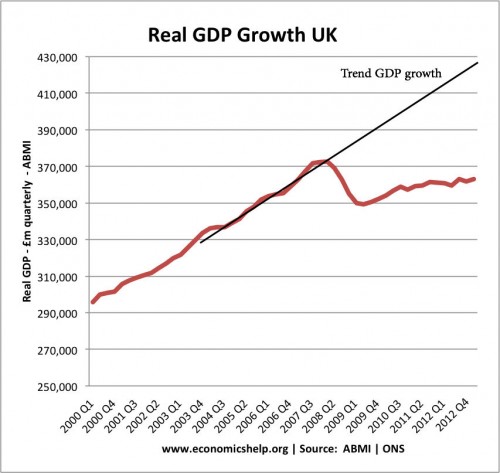

The other lessons of the past five years is the limitations of traditional monetary policy. In normal circumstances a cut in base interest rates from 5% to 0.5% would ensure economic recovery. However, in the great recession, cutting bank base rates has been insufficient.

Firstly, commercial bank rates haven’t fallen to match base rates. This has been a particular problem in the Eurozone with bank rates in Spain and Greece, higher than before the crisis. See bank rates and base rates

In the aftermath of the credit crisis, liquidity shortages have meant the supply of credit has constrained lending, investment and growth. In other words reducing the cost of borrowing is insufficient to boost demand, if the supply of credit isn’t there.

3. Quantitative easing ineffective.

It is still hard to quantify the effect of Quantitative easing. It is largely an untried policy. But, the experience of the UK is disappointing.

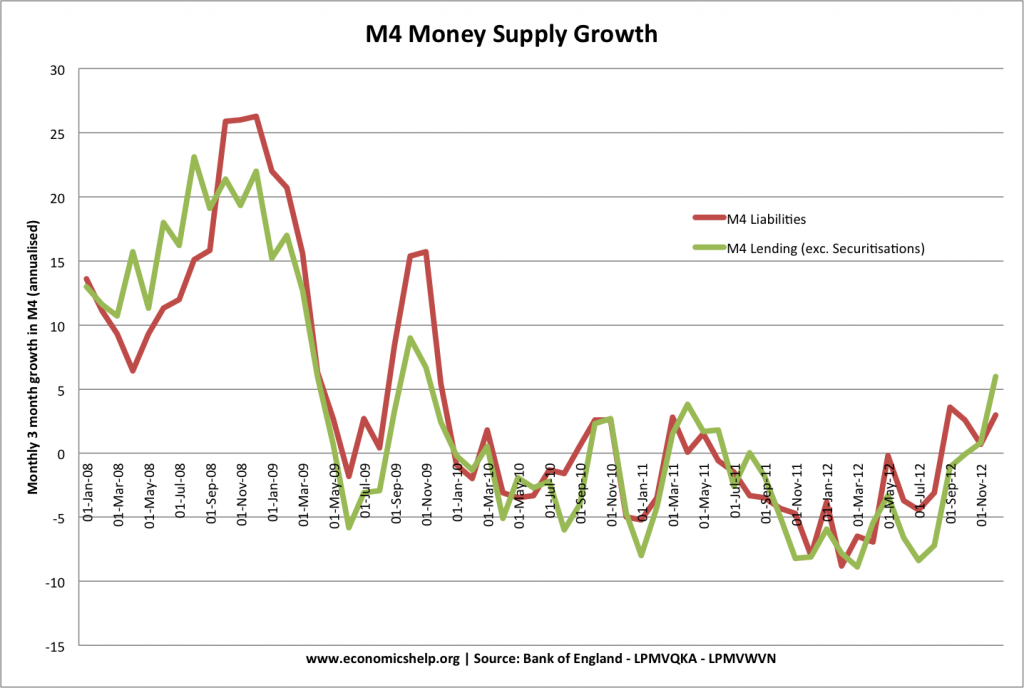

Despite creating over £300bn of extra money, quantitative easing failed to translate into higher broad money supply growth. Quantitative easing largely swelled the reserves of commercial banks, but didn’t translate into higher bank lending. However, in evaluation, without quantitative easing, the recession may have been even deeper.

Figures for money supply M4 give a broader understanding of economic activity than headline inflation rates. Though little attention has been given to M4.

4. Role of Lender of last resort

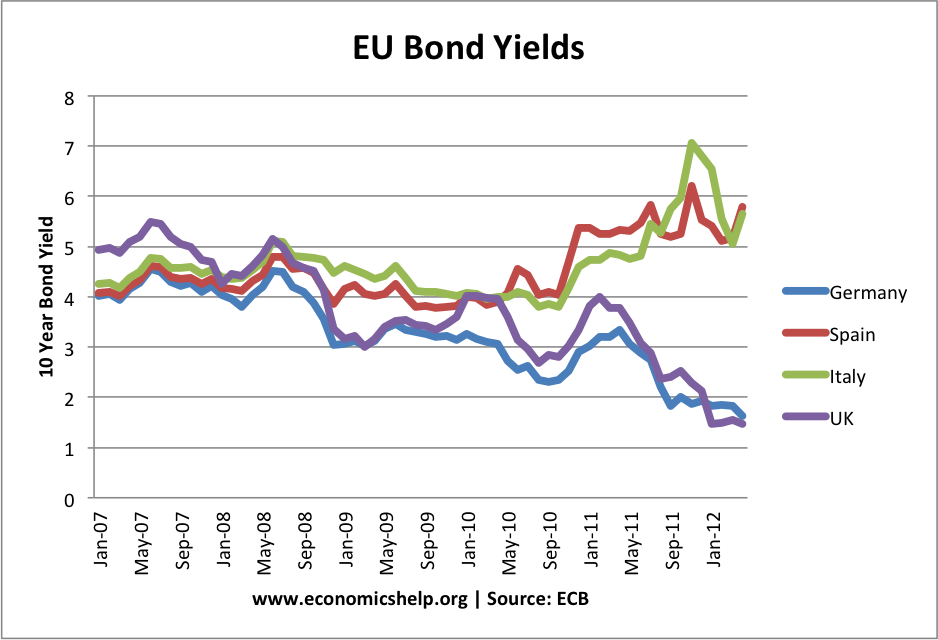

Before the crisis, Central Banks didn’t need to intervene in the Bond market. However, the crisis has shown the importance of Central Bank intervention to avoid panic rises in bond yields – and the subsequent panic to cut budget deficits.

In late 2012, the ECB finally agreed to undertake whatever it takes to save the Euro. This brought down bond yields in the peripheral countries. But, it raises the question, why did they wait two years? If the ECB had been willing to intervene earlier, they could have prevented the rapid rise in bond yields. They could have reduced an unnecessary interest rate burden for governments which made deficit reduction more difficult. Most importantly, without the panic rise in bond yields, Eurozone economies would have faced less pressure to instigate harsh austerity measures which have reduced demand and economic growth. In this regard, the Bank of England showed the benefits of an independent Central Bank. The crisis also showed the inertia that the ECB can have when faced with a crisis.

5. Inflation targeting too narrow

Back in 2007, it was possible to look at headline economic statistics and come to the conclusion everything was fine. Inflation was low, economic growth positive. No sign of an economic boom and bust. However, there was an unsustainable in bank lending, and asset prices. This shows that it is insufficient to look at inflation. Financial instability can undo all the work of monetary policy.

In evaluation, Central Banks couldn’t have prevented the financial bubble and housing bubble through interest rate policy alone. The boom and crisis showed that interest rates are limited for dealing with the much wider range of economic and financial problems. To prevent the financial bubble would have required a wider range of financial instruments and policies.

Conclusion

The past five years have been very challenging for any Central banker. Given deep recession and cost-push inflation, Policy makers have faced a very unwelcome trade off. However, from the crisis, the most important to lessons to learn would be:

- The limitation of inflation targeting.

- The importance of Central Banks considering economic growth and unemployment.

- The insufficiency of using interest rates to control overall macro-economic stability

- The role of the financial sector in influencing macroeconomic stability.

- The importance that a Central Bank has in acting as lender of last resort and willingness to intervene in bond markets, if necessary.

Related

Industrial production is down and consumption is suffering because families are not spending. The nations’s administrators have to listen to the specialists in the economic crisis who know how to deal with the many problems linked to the economic crisis. They need the assistance of specialists like those from the Orlando Bisegna Index who are very familiar with the problems of unemployment, lack of family purchasin power, and public finances and have solved these problems for counties in financial distress and gotten them out of debt and default.

Section 4 above conflates the problems facing the ECB with the problems facing the central bank of a country that issues its own currency. They’re actually very different.

For example having the ECB support the bonds of periphery countries is a risk for core country creditors: given the lack of competitiveness of periphery countries, periphery countries might just default.

Also there is some rhyme and reason behind periphery austerity: the aim is to get periphery costs down. And that medicine IS WORKING. It’s working far more slowly than we’d like, and at horrendous social cost. But that’s common currencies for you: common currencies have advantages and disadvantages.

It is an interesting quirk in the system that whilst capitalist economics promotes competition in every market as a route to efficiency, central banks operate under pure monopolies. This was discussed when I attended a prominent debate involving Stephen D. King – a leading bristish economist. You can see more here;

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jj33b_8MnU0