Secular stagnation is a term coined to describe a prolonged period of lower economic growth. Economists, such as Larry Summers have written on secular stagnation arguing the world has entered a period of substantially lower economic growth. He points to factors, such as ineffective monetary policy and weak demand for explaining the lower rates of economic growth. Other factors that may explain lower economic growth include a hangover from the credit crisis, but also supply side and demographic factors (e.g. ageing population).

Secular stagnation is related to the concept of a liquidity trap. The idea that in certain circumstances low interest rates are insufficient to boost demand because of structural issues.

An important debate is the extent to which this period of lower economic growth is due to temporary demand side factors – or whether this period of lower growth is due to underlying structural issues and is therefore likely to last for a considerable time.

What is secular stagnation?

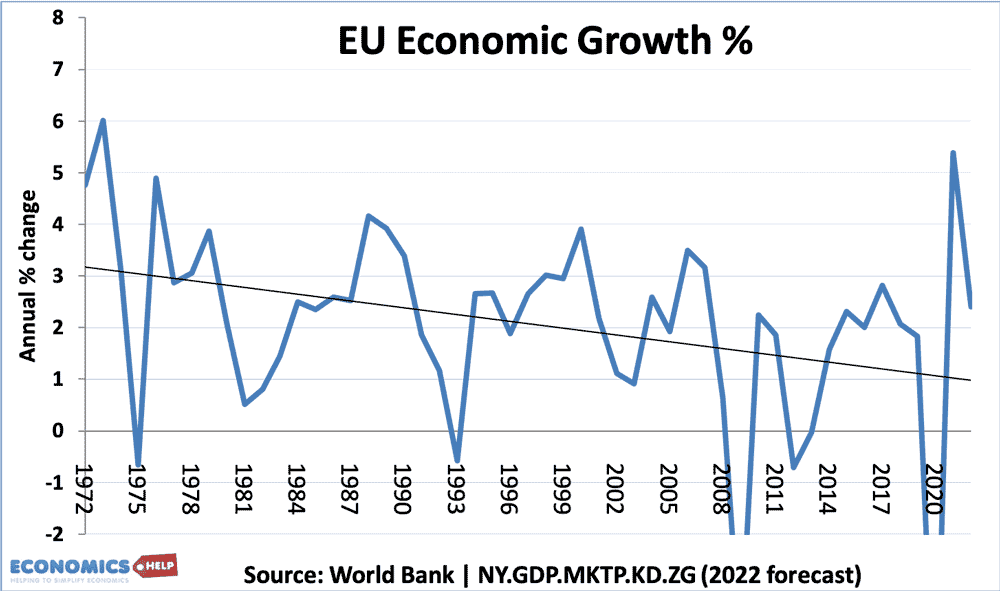

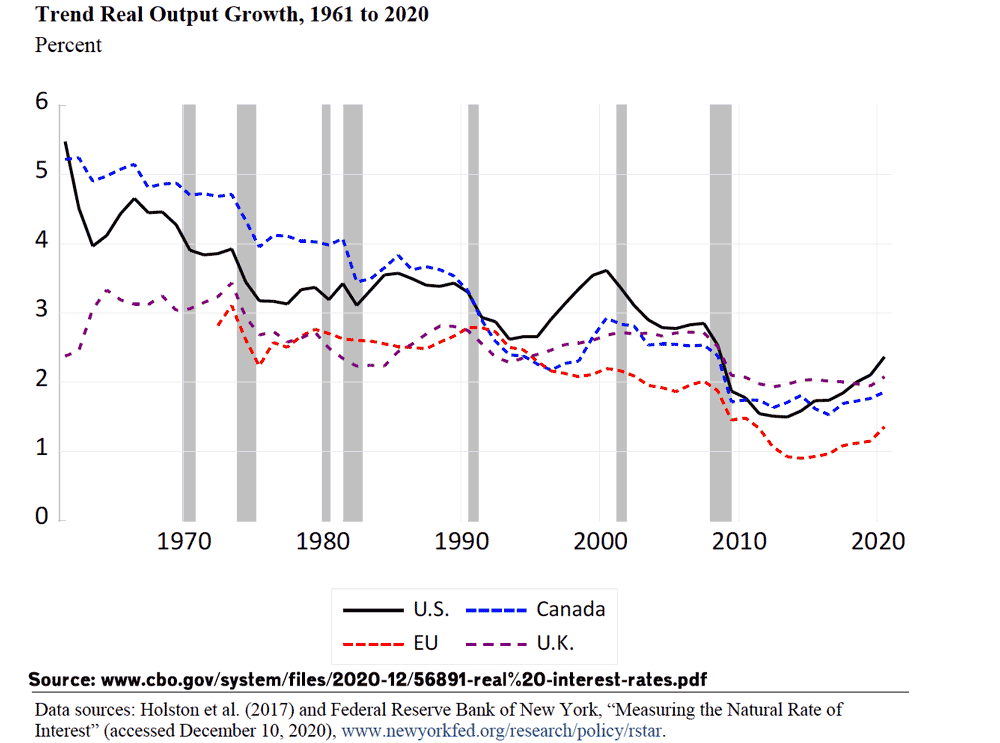

Primarily secular stagnation refers to lower rates of economic growth. In the past 50 years, we can see a downward trend in rates of economic growth in major economic blocks.

EU economic growth

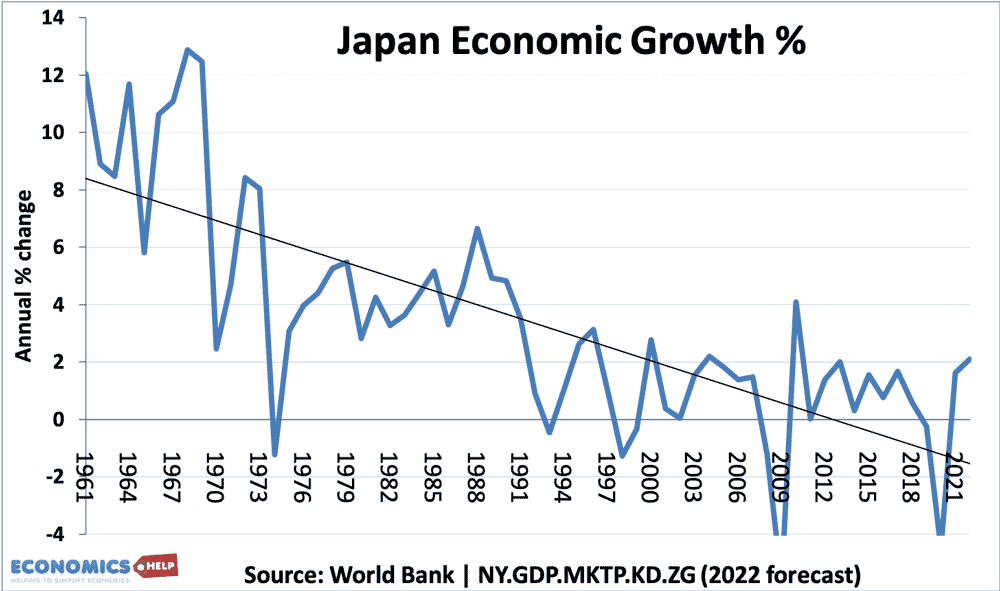

Japanese growth

Japan has seen the biggest drop in rates of economic growth – from the boom years of the 1960s, 70s and 80s, the economy has struggled with very low rates of growth since the mid 1990s.

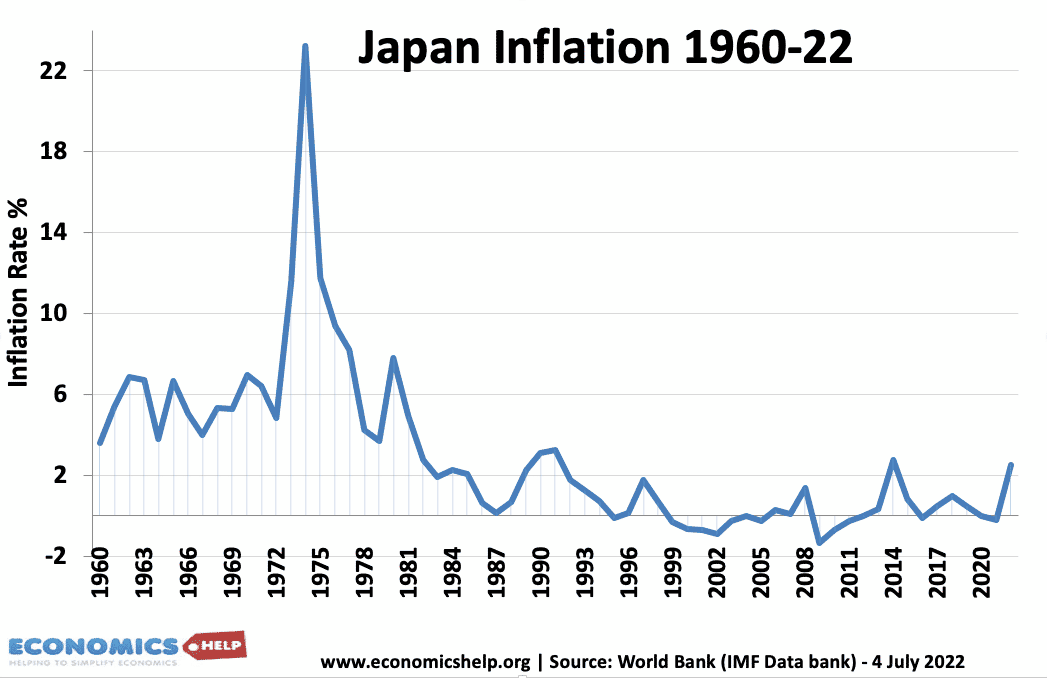

Japan inflation struggled to exceed 2% since the mid-1980s.

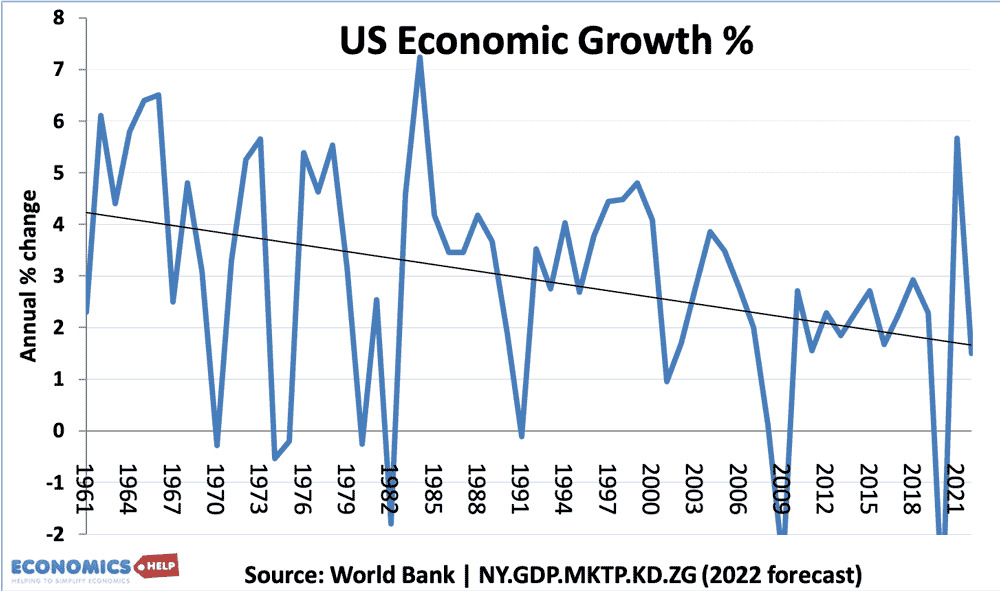

US growth

The downward trend is smallest for the US economy. The US economic recovery, post-2008, has been stronger than many other developed economies. But, still, there is a strong indication of a lower long-run trend of growth in the US.

Source: Business economics Vol 49. no. 2

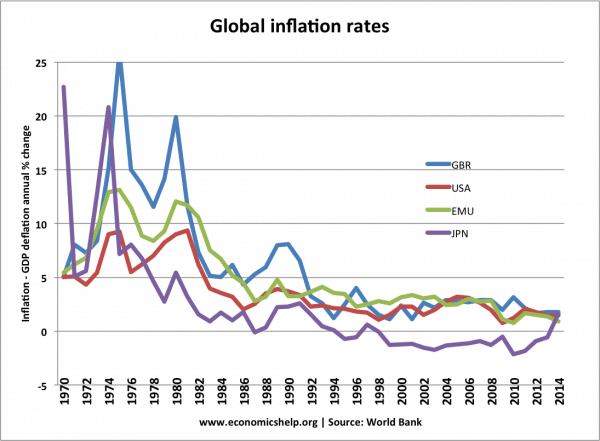

Lower rates of inflation

Another feature of secular stagnation has been disinflation – a falling rate of inflation – getting close to deflation. Deflation creates many problems, such as making monetary policy ineffective and increasing real interest rates.

What causes secular stagnation?

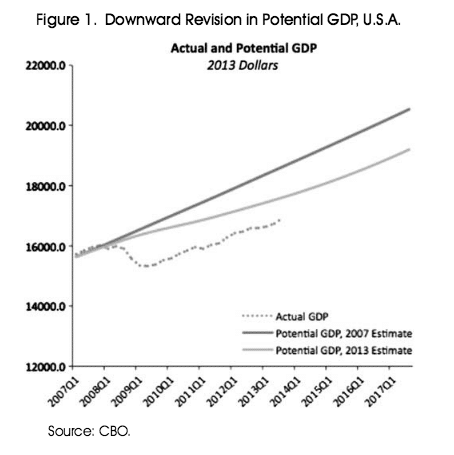

1. Financial crisis. The credit bubble and bust of 2008 was a big factor in precipitating a fall in economic growth. The bank losses have led to lower bank lending and lower investment. The financial crisis has also undermined business and consumer confidence making a normal recovery much weaker.

2. Lower capital investment. In recent years, we have seen lower levels of capital investment around the world. This fall in capital investment has been aggravated by:

- A fall in the price of commodities – reducing demand for capital investment in commodity production.

- Lower business confidence due to low rates of economic growth and financial concerns.

- Access to credit more limited due to previous bank losses.

- China has been enjoying an investment boom, but many fear they may now have over-reached and with over-supply, their investment cycle may swing into a downturn.

3. Problems in the Eurozone

In the post-war period, Europe experienced rapid rates of economic growth. But, in recent years, the Eurozone has slowed down considerably aggravated by the global downturn but also aspects of the Euro single currency.

- Internal devaluation. Without the possibility of exchange rate devaluations in the Euro, countries with higher inflation rates have been focusing on internal devaluation to restore competitiveness and reduce current account deficits. Internal devaluation, involves deflationary policies, lower wages and attempts to reduce prices – which invariably leads to lower aggregate demand and lower economic growth.

- Austerity to reduce budget deficits. Many Eurozone economies have faced pressure to reduce budget deficits because of EU rules on borrowing. This has led to fiscal tightening with little accommodation in monetary policy.

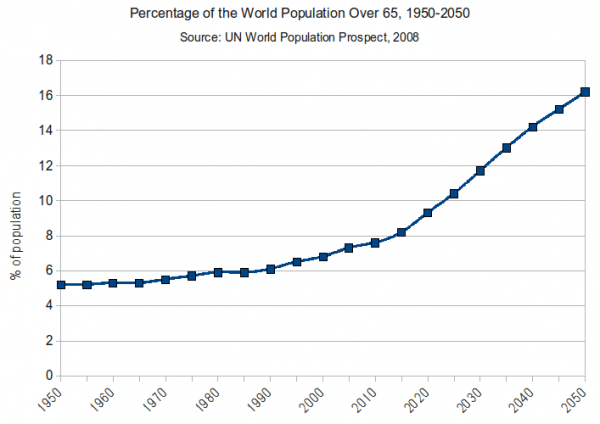

4. Demographic changes

Many developed countries are seeing a fall in the birth rate. Leading to an ageing population and a declining population. For example, the population of Japan is forecast to fall 25% from 127.8 million in 2005 to 95.2 million by 2050. This leads to a smaller workforce and lowers potential productive capacity. An ageing population also increases the dependency rate and may require higher taxes to meet pension and health care commitments. European countries, such as Italy and France are facing similar demographic changes. For example:

- The old age support ratio, the number of workers aged 20-64 relative to those aged over 65. is falling across the globe.

- In 1950, the ratio was 6.99 in Italy. In 2010 it was 3.00. By 2050, it is forecast to fall to 1.46. (Economist.com)

- (See also: problems of an ageing population)

- In the US, the percentage of the population over the age of 65 is forecast to rise from 15% in 2016 to 24% by 20160.

5. Diminished technological advancement

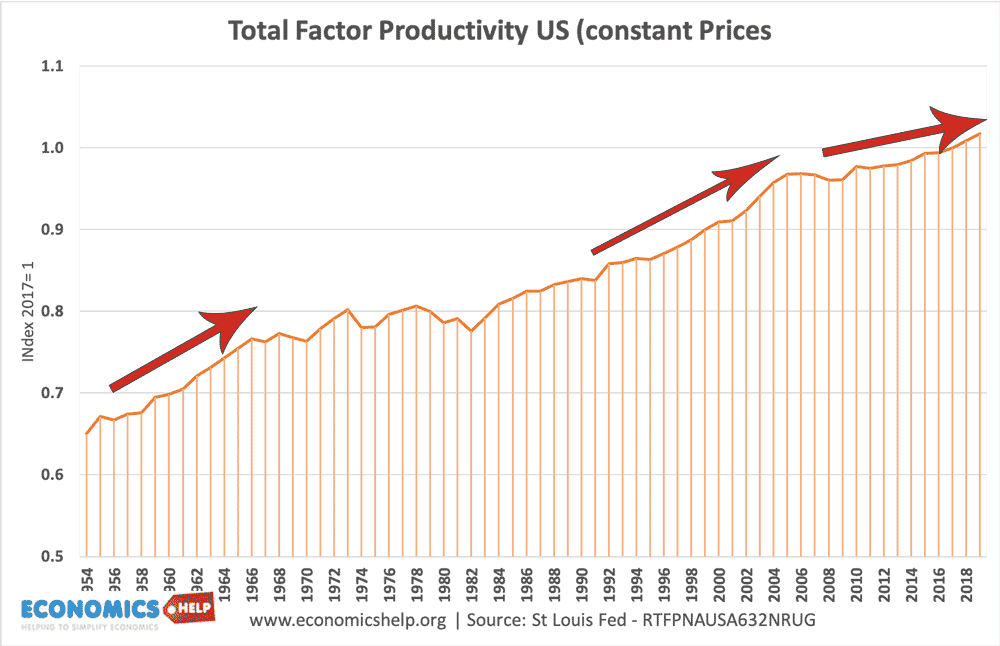

Some argue that we may be entering a period of limited technological advances which will limit the growth of productive capacity and potential GDP growth. This is controversial as others argue that people often underestimate potential technological improvements. The above graph shows total factor productivity in the US. It shows how productivity growth has been at a slower rate since mid 2000s than during 1950s or 1990s.

6. Deflationary Pressures

The experience of Japan in the 19990s and 00s suggests that once low inflation/deflation gets established in the economy, it can be difficult to budge. There is a concern that the Eurozone is likely to get stuck in a low inflation environment and this will curtail growth – especially since the ECB has proved to be very conservative in aiming for higher inflation / nominal GDP.

7. Hysteresis and negative multipliers

Hysteresis is a theory that what happens in the past has a strong influence over the future. In other words, a cycle of low growth and low investment creates an environment where low growth and low investment persists. For example, eight years after the start of the credit crunch, we should have escaped the financial crisis and temporary problems. But, the low growth and period of low-interest rates have persisted much longer than many expected. Hysteresis may be a factor in making the stagnation last longer.

8. Supply side

Others place the low growth on supply-side factors. For example, heavily regulated labour markets and high taxes. However, although there may be scope for supply-side improvements, it doesn’t explain the sharp drop in economic growth post-2008, given that hasn’t been a corresponding increase in taxes and regulation during this period.

How to overcome secular stagnation?

I will save this for a future post. But, in brief, possible policies include:

- Demand side policies – expansionary fiscal policy (but this is ultimately limited for dealing with supply-side factors)

- Unconventional monetary policy – Q.E.

- Change expectations by targeting higher inflation.

- Increase population, e.g. through immigration

- Supply-side policies – structural reform to promote investment and innovation.

Related

In the bad behavior of the global economy, it may also be due to causes of geopolitical strategies and shifting power sources economic zones during the boom of Japanese, European and USA, had no relevance as are the Brics and Southeast Asia, behold, another point of view that can determine which times of very low growth for economies that marked the guidelines in this sector come.

How about debt levels? Individual, business and government debt levels have grown year after year. And interest rates are currently on the floor, well the central bank one(s). The expansion of credit is once again strangling the economy. We have seem to have forgotten what productive lending is; there’s too much lent and too much is unproductive. Also the money supply is constricted, and merely expanded by private banks, often merely for inflating house prices.

Deleveraging was a factor immediately after the crisis, but I don’t believe it explains the continuing levels of low growth globally. In the longer run, underlying economic fundamentals and the supply-side needs to be improved, especially investment in innovation. Meanwhile in the short-run, a lot of issues source from lower inflation expectations and central bank’s losing credibility. This influences confidence and real interest rates. I would certainly support a rise in inflation targeting in the developed world, yet this will have no effect if credibility remains as it is. As Paul Krugman put it all the way back in 1998 “Credibly promise to be irresponsible”, such a ploy has finally been adopted by the BoJ, announcing their intentions to overshoot the inflation target of 2%. Maybe this is just the normal, in which case I would say that two factors are to blame, slow-down in innovation and ageing population.

Secular strangulation began in 1981, with the saturation in commercial bank deposit account innovation.

As professor Lester V. Chandler originally theorized in 1961, viz., that in the beginning: “a shift from demand to time/savings accounts involves a decrease in the demand for money balances, and that this shift will be reflected in an offsetting increase in the velocity of money”.

His conjecture was correct up until 1981 – up until the saturation of financial innovation for commercial bank deposit accounts.

I.e., the saturation of DD Vt according to Marshall D. Ketchum (Chicago School): It seems to be quite obvious that over time the “demand for money” cannot continue to shift to the left as people buildup their savings deposits; if it did, the time would come when there would be no demand for money at all”

definition

Secular stagnation is a term coined to describe a prolonged period of lower economic growth.Primarily secular stagnation refers to lower rates of economic growth.

What causes secular stagnation?

1. Financial crisis.

2.Lower capital investment.

3.Problems in the Eurozone

4.Demographic changes

5.Diminished technological advancement

6.Deflationary Pressures

7.Hysteresis and negative multipliers

8. Supply side