Cost-push inflation is caused by higher costs of production, such as rising oil prices, higher nominal wages, and increased commodity prices. To reduce this kind of inflation, the government can pursue deflationary monetary policy and/or supply side policies. But, in truth, it is difficult to reduce cost-push inflation because higher interest rates are likely to cause a bigger problem of recession, and supply side policies, even if successful, will take a considerable time to take effect.

Policies to reduce cost-push inflation

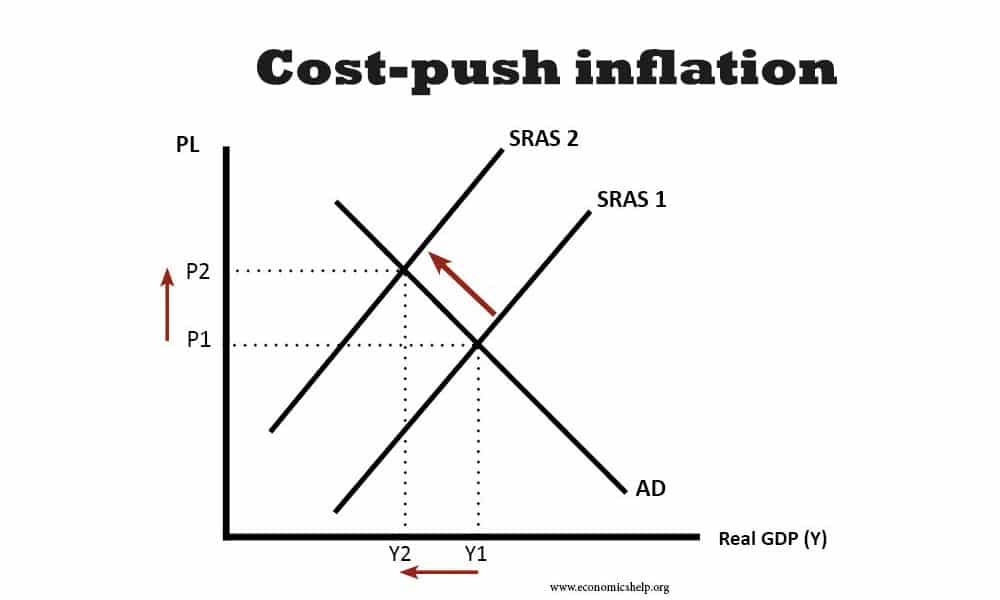

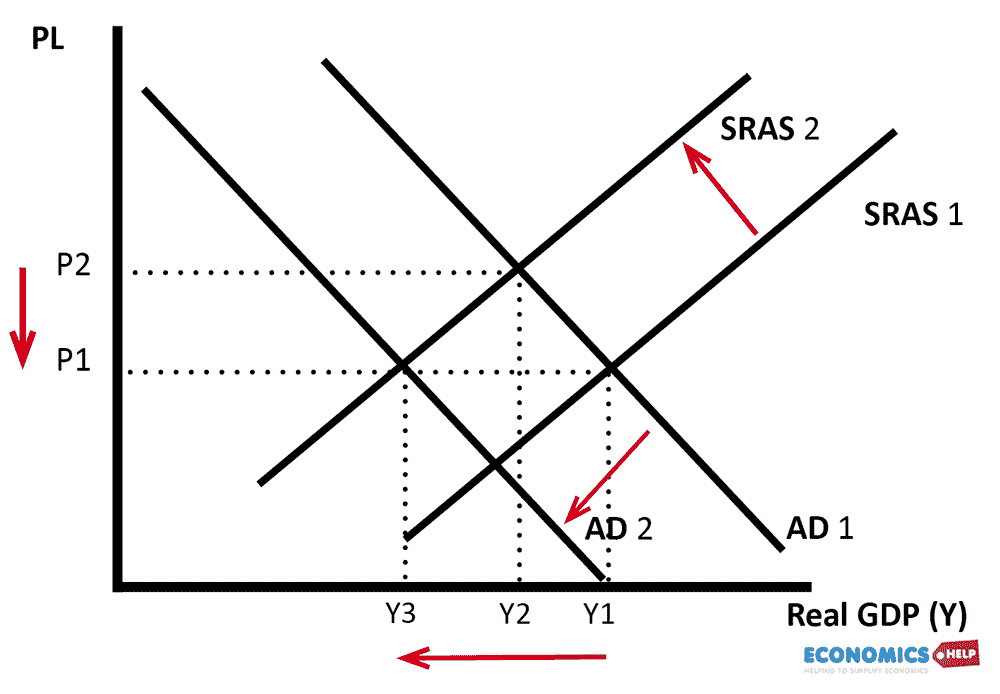

Cost-push inflation can be represented by the short-run aggregate supply curve shifting to the left. This highlights the difficulty policymakers face – it is not just higher inflation, but also lower economic growth. Inflation can be reduced by raising interest rates. Higher interest rates increase the cost of borrowing and discourage consumer spending and investment. Higher rates will also tend to cause appreciation in the exchange rate – reducing the price of imported goods. All this will reduce inflation, but also reduce economic activity and lead to economic growth.

The diagram shows how demand-side policies to reduce cost-push inflation can cause an even more serious issue of recession (which will also cause a rise in unemployment.)

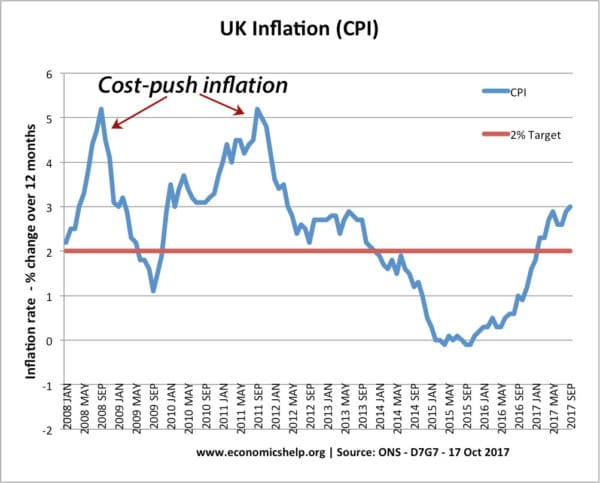

This is why when there is cost-push inflation, Central Banks usually take the decision to allow inflation to remain high, expecting the cost-push inflation will remain temporary and not permanent.

For example, in the post-2009 period, the UK had a few experiences of cost-push inflation (higher oil prices, devaluation of Pound increasing import prices). However, the Bank of England decided not to increase interest rates and leave inflation to its own devices.

Interest rates were cut in March 2009 to 0.5% and remained at 0.5% through the 2012 cost push inflation.

Cost-plus inflation + demand-pull inflation

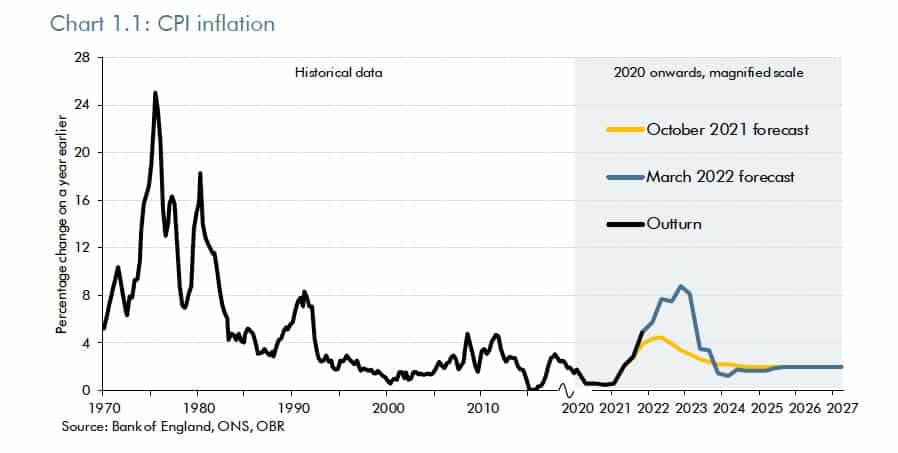

In 2021/22 there is a combination of both cost-push inflation and some demand-pull inflation. The demand-pull inflation is from strong economic recovery from the end of Covid lockdowns. With inflation forecast to rise to 8%, the Bank of England will increase interest rates to deal with the demand-side cause of inflation. In the US, the Federal Reserve has hinted at modest interest rate rises to perhaps 2% by 2023 – due to high inflation and a tightening labour market.

Supply-side policies to reduce cost-push inflation

Given the limitations of demand-side policies in reducing cost-push inflation are there any effective supply-side policies to reduce cost-push inflation?

Firstly, it is important to look at what is causing the cost-push inflation. For example, in 2022, cost-push inflation is caused by

- Rising energy prices (shortage of oil/gas) exacerbated by Ukraine war.

- Rising shipping costs due to congestion at ports and lockdowns in China

- Rising commodity prices

- Bottlenecks in global supply chains due to unexpected demand following end of Covid lockdowns

- Tightening labour market and some nominal wage inflation.

1. More flexible energy policies

A key driver of cost-push inflation is a rise in oil/gas prices. As a key commodity, higher oil prices have knock-on effects on other consumer prices. One solution is to have stockpiles of oil that can be released during times of crisis. For example, in March 2022, President Biden ordered the use of oil from America’s strategic reserve (1 million barrels a day). This increase in supply will help to limit the price increases of oil, though it still represents a very small share of total oil demand. For example, Russia currently exports 5 million barrels of crude oil a day. (Link)

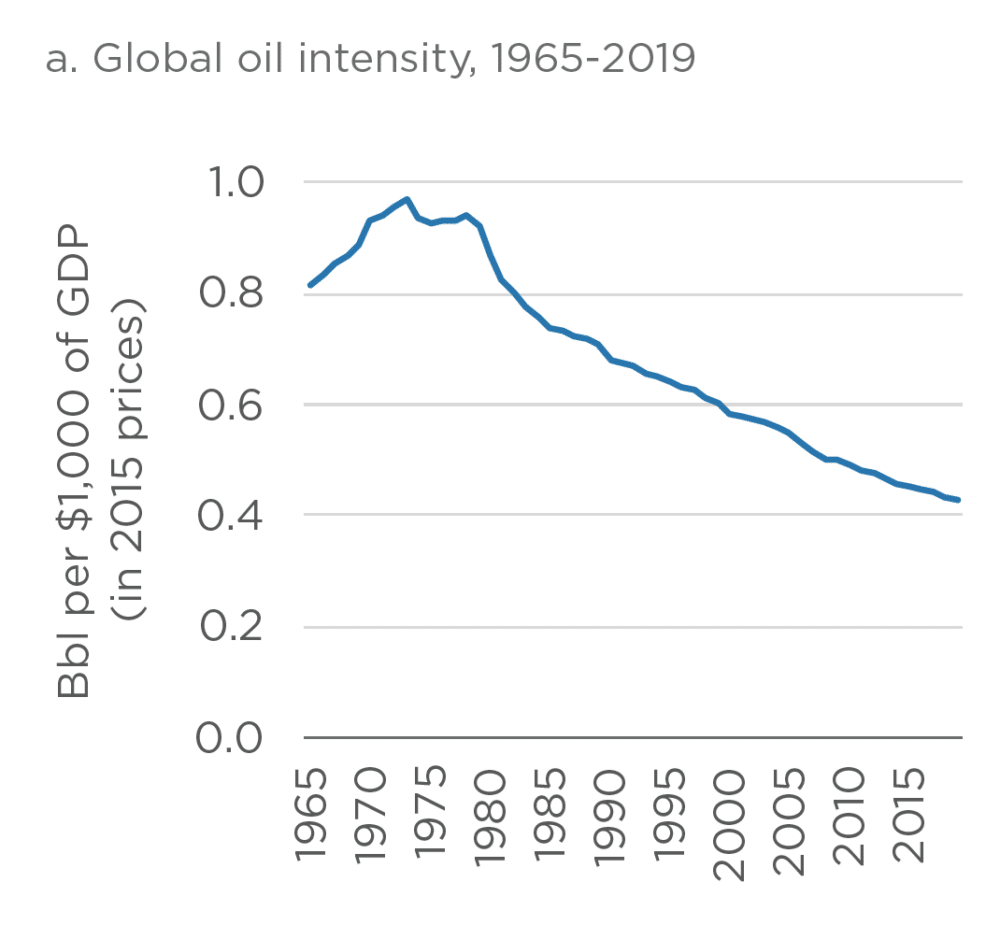

In the longer term, investing in alternative sources of energy, that are less dependent on imports of fossil fuels. For example, governments and energy companies could invest in wind power, solar power, hydrogen power and geothermal energy. This greater diversification of energy sources will help to reduce the reliance of the economy on oil. This will obviously take a long-time, but it is worth observing, that the inflationary impact of higher oil prices is much less than in the 1970s. (see: how much oil affects inflation)

This shows the decline in the importance of oil meaning a rise in oil prices have less significant effects on inflation than previously.

2. Reducing transport bottlenecks

In 2022, the great bottleneck has been shipping. This is primarily managed by the private sector, so there is only so much a government can do. Building or encouraging more shipping capacity could help in the long-term, but by the time it is built, the temporary bottlenecks will probably have been solved. Still there are some transport bottlenecks the government can reduce by investing in road, rail and freight, but the impact on inflation will be very minimal.

3. Price cap on monopolies

One policy floated during high inflation is imposing price caps on firms with excessive monopoly power. The argument is that when there are supply shortages, monopolies can use their market power to increase prices and exacerbate the situation. Government price controls, could, in theory, limit price increases. Price controls have pros and cons. The main problem is that if prices are artificially reduced by government price controls, it can lead to shortages and rationing. During the Second World War, price controls were effective in reducing the inflation rate, but they had to be accompanied by rationing that may not be acceptable in peacetime.

4. Government intervention.

If a key component of cost-push inflation is rising energy bills, the government could decide to absorb price increases. For example, in France the nationalised energy companies have been instructed to limit price increases to 4%, causing a €8.4bn (£7bn) financial hit to French energy company EDF (link). By contrast in the UK, OFGEM have allowed prices to rise 54% reflecting market forces. As a result, French inflation will be lower than UK inflation. It is quite an effective policy for preventing cost-push inflation, though it leads to lower profits/loss for energy companies in the short term.

5. Reduced power of trade unions

In the 1970s and early 80s, rising wages were a factor behind cost-push inflation (and also behind demand-pull inflation). Policies to reduce trade union power and end inflation wage increases could tackle this cause of inflation. In 2022, there is a very different labour market. Union power is very limited and so there is little scope for reducing wage inflation by reducing union power.

Video

Further reading

Improve immigration policies to address staffing shortages and rising wages.

This was so helpful and equally interesting…..Thanks much.

I think with could as well reduce cost-push inflation by; encouranging home based production especially when it comes to foodstuff….