- UK bond yields are the rate of interest received by those holding Government bonds.

- Governments sell bonds (also called gilts) via the Debt Management Office to fund their budget deficits. Bonds are a way for the government to borrow – a bit like the government taking out a loan.

- Government bonds are frequently traded on bond markets. Therefore, their market price may be quite different to the original price set by the government.

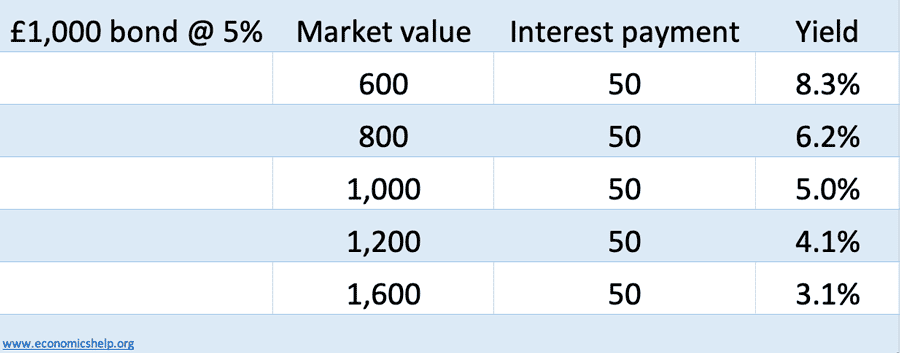

Example of why bond yield changes

A government may sell a 10-year, £1,000 bond at 5% interest. This means every year the government will pay £50 to the holder of this bond.

- If demand for government bonds rose, this £1,000 bond would increase in price as investors pushed up the market price.

- But, the government still pay £50 a year interest until maturity. If the market price of the bond rises to say £2,000, the interest rate (yield) is now 2.5% (50/2,000)

- Therefore higher demand for bonds leads to lower bond yields.

- Conversely, if people sell bonds, this pushes up the bond yield (e.g. what happened in UK September 2022)

How a change in price of a bond changes the effective yield

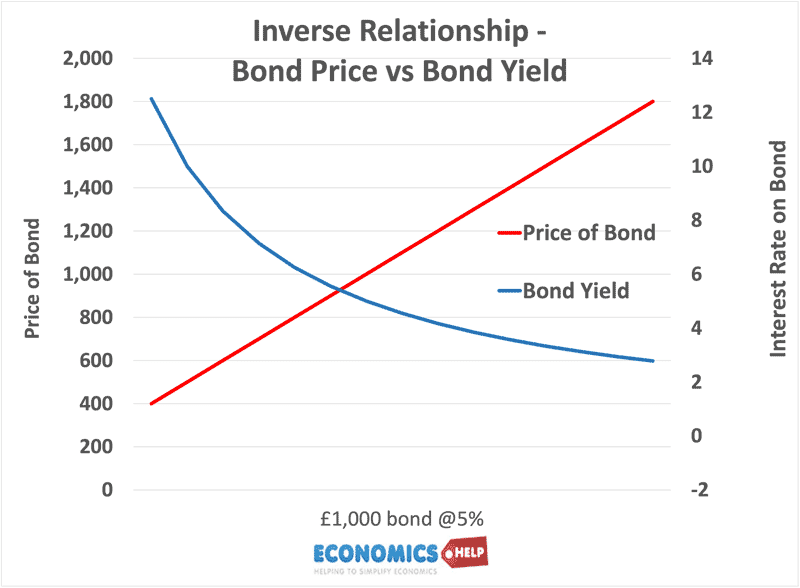

The law of the bond market

- As bond value rises, interest yield falls

- As bond value falls, interest yield rises

Video summary

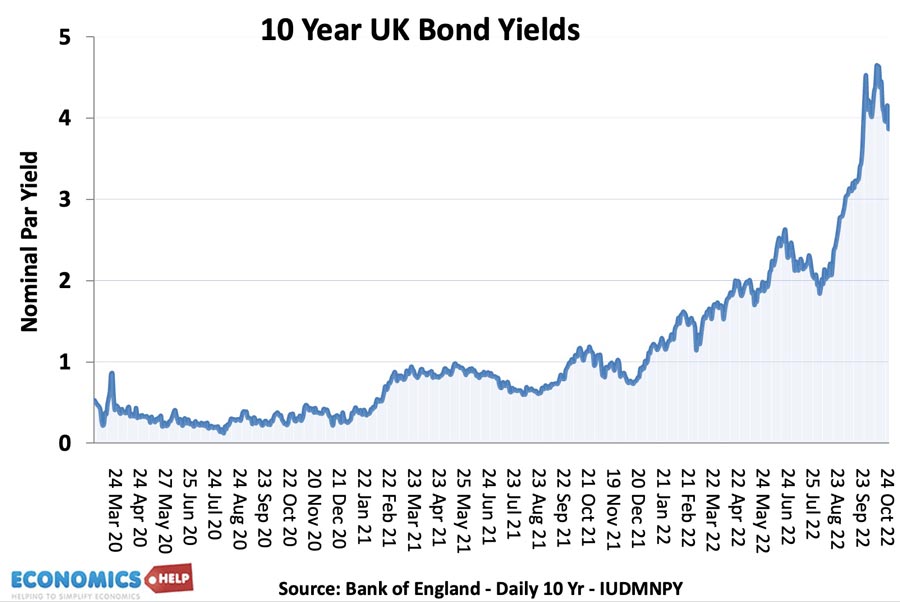

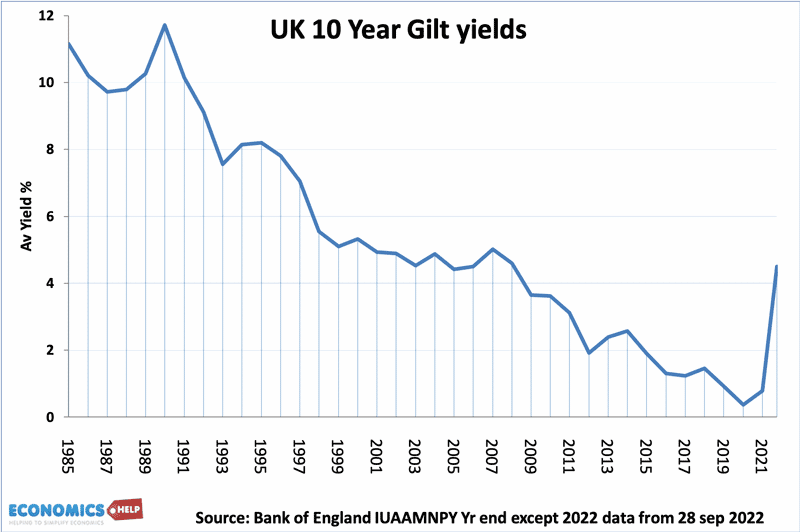

Recent UK Bond Yields

Source: Bank of England – 10-year bond yields

What is the importance of bond yields?

- Cost of Government Debt. If bond yields fall then the government can issue debt at low-interest rates. This makes it cheaper for the government to borrow. The UK spent around £45bn on interest payments in 2011/12 and £83bn in 2022. If bond yields were higher, this interest rate cost would be much greater.

Example. In 2022, UK debt is £2,347bn.

- If the average bond yield is 3.75%, annual interest is £88bn.

- If average bond yield rose to 5.5%, the net annual debt interest payments would be £129bn.

That is an extra £41billion – just from higher bond yields. It is worth noting that if bond yields rise, it will take longer for the average bond yield to rise because government debt is issued on a rolling pattern. i.e. Government debt is financed by bonds sold over the past 30 years.

- How Much Can a Government Borrow? If interest rates are low, this is an indication markets are willing to buy government debt. Therefore, the government can borrow more. If bond yields rise sharply, this indicates the private sector no longer wish to buy government bonds, and therefore the government will face much greater pressure to reduce borrowing soon.

- Forecast of future growth and inflation. Low bond yields may indicate an unwillingness to invest in private sector investment and reflect low growth.

- Future Inflation. Bond Yield curves can indicate future inflation trends. (see below)

- Rising bond yields may cause stock market falls. If bond yields rise, investors may prefer to sell stocks and buy bonds which give better yield.

- Corporate bonds. It is not just governments who sell bonds, companies do too. Corporate bonds are a way for firms to raise finance and fund investment. If bond yields rise, firms find it more expensive to borrow and invest.

- Crowding out. If government bond yields rise significantly. It will make government bonds more attractive and investors will lend government money, rather than lending to firms. This is known as financial crowding out.

Why did bond yields surge in September 2022?

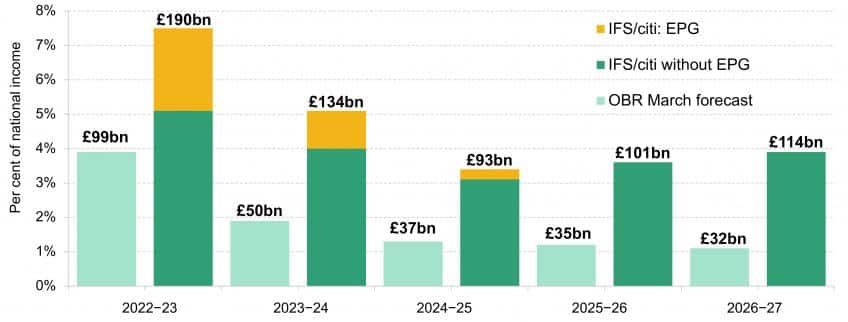

In the UK, Sept 2022, inflation was running at 10% and the economy at risk of recession. The government announced a huge fiscal expansion (involving tax cuts for high earners and an energy price guarantee) which saw the budget deficit soar.

The IFS believed the budget meant the UK debt was on an unsustainable path. Also the fiscal expansion alone was likely to raise inflation. Markets saw UK debt as riskier and investors sold on expectations of higher inflation, higher interest rates. See: Truss Economics – Will tax cuts save the UK economy?

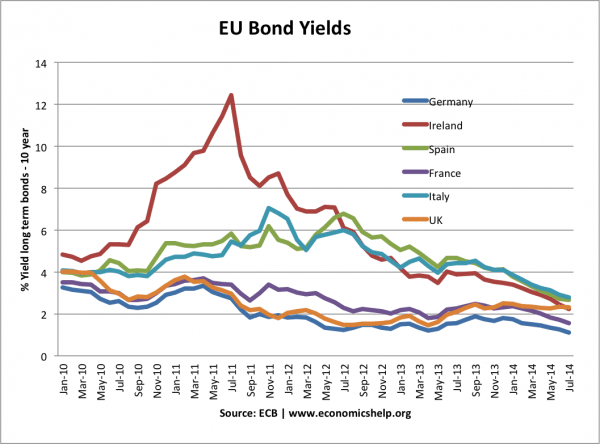

2011/12 – Why UK bond Yields fell and Italy bonds rose

Around 2010-12, in some Eurozone economies, bond yields rose very rapidly because of fears over government debt. The UK had very high annual borrowing (2011/12 annual deficit – nearly 10% of GDP). Yet in the UK , bond yields have fell. This was because:

- Increase in savings rates in the UK. Higher private sector savings have increased demand for secure assets such as government bonds

- Poor returns in the private sector. The double dip recession made investing in the private sector less attractive. Investors would rather have the security of government bonds with low-interest rates than riskier shares and private sector investment.

- Quantitative Easing. The policy of Q.E. and the purchase of government bonds by the Bank of England has helped keep bond yields low.

- A big reason UK yields were low is that they were not in the Eurozone, but have their own currency and can create more money if necessary. There are no fears of a liquidity crisis in the UK because the Bank of England can always print money if necessary.

- Until 2012, Eurozone economies didn’t have a Central Bank willing to do this – so have been more susceptible to investor concerns.

See also: Factors that determine bond yields

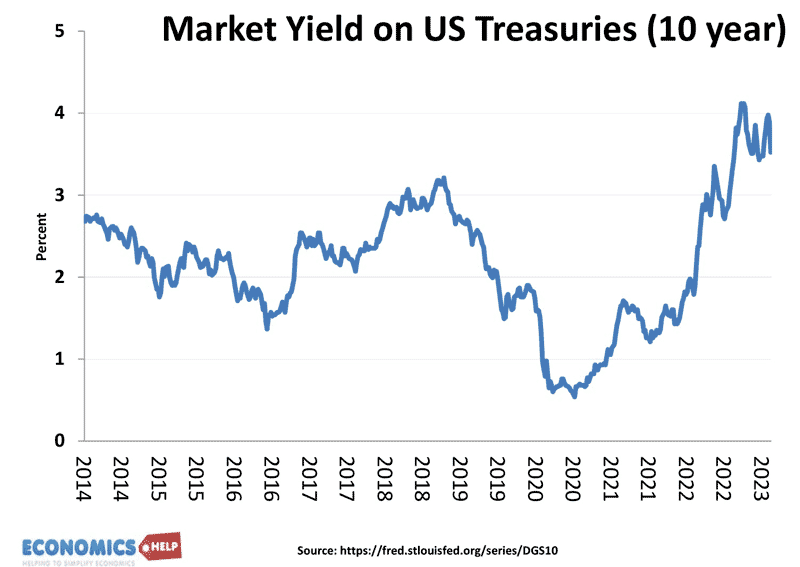

US bonds

US bonds rose from 2020 to 2023 due to higher interest rates as the economy grew strongly and inflation rose. Interest rate rose causing a fall in the price of bonds. This caused several US banks to have unrealised losses on their assets and was a major factor behind the failure of Silicon Valley Bank. Are we heading towards new credit crunch?

History of UK bonds since 1984

This shows the bond yield on 10-year government bonds since 1993.

Higher bond yields in the early 1990s were a reflection of higher inflation rates. Investors needed a higher yield to compensate for inflation eroding the value of savings. As inflation and interest rates fell in the 1990s and 2000s, so did bond yields.

Importance of bond yields

“I used to think if there was reincarnation, I wanted to come back as the President or the Pope or a .400 baseball hitter. But now I want to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everyone.”

– James Carville, Bill Clinton campaign strategist

The bond market is often quite quiet and not much happening, but sometimes the bond market can destabilise a government and force it to change its policy.

Examples of when the Bond market changed government policy

The austerity of 2011. After the great financial crisis of 2008/09, European economies went into recession. Budget deficits rose and investors started to see southern European bonds as risky. In the Euro (at that time) the ECB was unwilling to intervene and provide liquidity for individual countries. Therefore, bond yields surged in countries like Greece, Spain, Ireland and Portugal. As a result, there was pressure on these countries to reduce government spending, and reduce budget deficits to (partly appease the bond market) This led to a deeper recession. The crisis ended in 2012 when new ECB chief Mario Draghi promised to buy bonds and ‘do whatever it takes.

The fear of the bond market was one rationale for UK austerity under Cameron and Osborne. Other economists argue the fear was misplaced because in a time of low inflation, markets were quite relaxed about government borrowing.

UK mini-budget of September 2022. As well as an energy price guarantee, the government introduced £45 billion of unfunded tax cuts at a time of high inflation. Markets were spooked because the rise in debt was very large and they had no confidence it was sustainable in the long-term. (more detail here). It led to a sell-off of gilts (bonds), and rising interest rates and the government were forced to u-turn on cutting the 45p tax rate and more pressure to cut spending. The Bank of England also intervened buying £65bn worth of gilts.

Carter / Reagan. In 1976, long-term bond yields were 8%. By the end of Carter’s administration, they had risen to 12% – meaning their value fell by a third. Markets blamed Carter on failure to reduce government spending and inflation. High-interest rates and inflation were a factor in Carter losing the 1980 election. It lay a framework for the philosophy of cutting government spending. Though Reagan increased the budget deficit by tax cuts and higher military spending. NY Times “What the bond market wants from President Reagan”

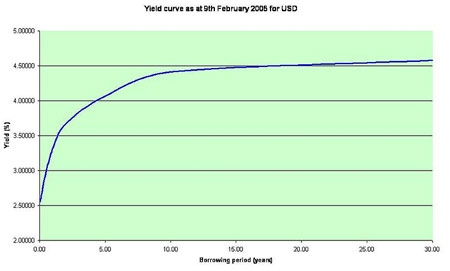

Bond Yield Curves

These show the interest rates for bonds of different maturities. Usually, bond yields on short-term debt (1 year or less) are low. Bond yields on longer-term debt (20,30 years) are higher. This is to reflect increased risk and likelihood of inflation in the long-term.

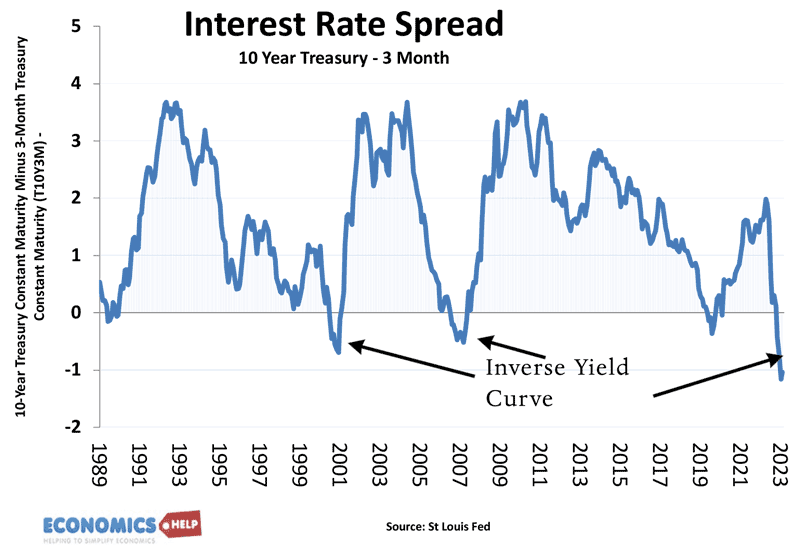

Interest Rate Spread

- The spread is the difference between the yield on a long-term bond and a short-term bond.

- For example, if a 30-year bond pays 5.00% while a 1-year bond pays 3.55%, the spread is 1.45%.

Inverted Yield Curve

Usually, bond yields on long-term bonds are higher than short-term bonds. This is because investors want risk premium of holding for long-time. However, in rare cases, the yield on long-term bonds can become less than short-term bonds. This is usually because Central Banks have increased interest rates to reduce inflation, but markets predict this will cause a recession, falling inflation and lower interest rates in the long-term.

An inverted yield curve is often a predictor of a recession as it was in 19990, 2001 and 2006.

Related

There seems to be a major error in the first section. A L1000 10 year bond at 5% will pay L500 of interest before maturity at which point you’ll get L1000 of principal back for a total of L1500 of disbursements. If it was prices at L2000, the effective rate would be notably negative, not 2.5%

If only bond math were that simple.

W – it’s not an error at all, it’s simply a different calculation of yield to the one you offer.

Under Current/Running Yield, which is presented here, the maths are exactly as simple as Tejvan presents. On the other hand, you’re referring to Redemption Yield or YTM. Arguably the latter is a more realistic estimate of returns *if* you hold the bond to maturity (which you’d be unlikely to do in the entirely theoretical case presented).

There’s a good article concerning the maths over at Monevator:

http://monevator.com/how-to-calculate-bond-yields/

Either way, not an error.

Thanks. Now I understand it.