Readers Question: What caused the massive decrease in the debt to GDP ratio for the UK following World War II?

It is a good question to ask. In the past few years, many European policymakers have felt that rising debt levels needed panic levels of austerity/spending cuts. But, that didn’t happen in the UK in the post-war period.

Summary

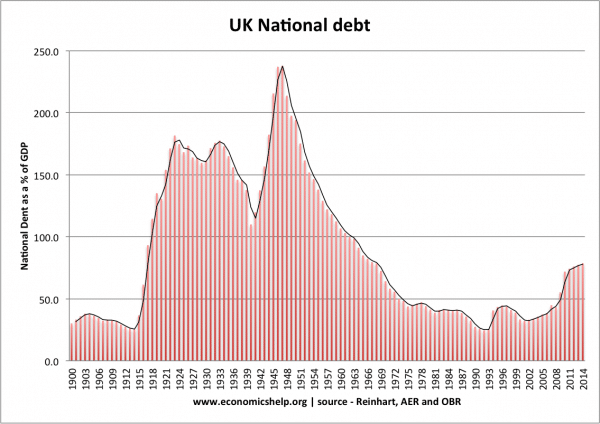

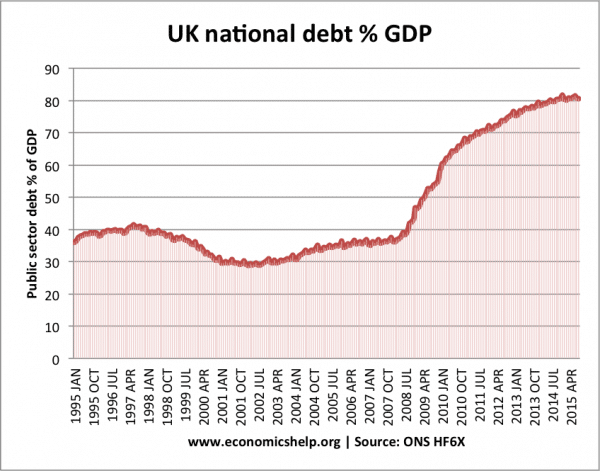

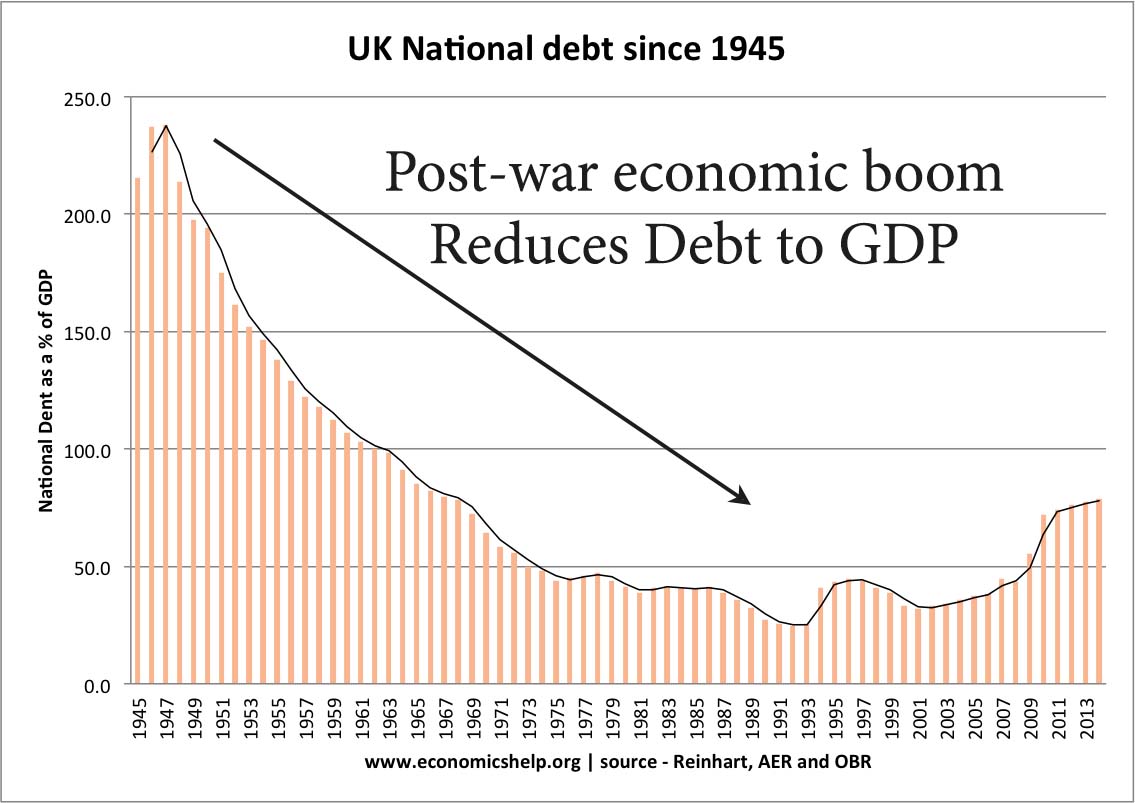

UK national debt peaked in the late 1940s at over 230% of GDP. From the early 1950s to early 1990s, we see a consistent decrease in the debt to GDP ratio. Using the above measure of national debt, UK debt as a % of GDP reached a low of 32% in 1993. (1) At the start of the global credit crunch in 2007, public sector debt was 38% of GDP.

ONS Datasets | Long run fiscal indicators PSA5A at ONS

In the past eight years, debt has increased to 80% of GDP but is beginning to stabilise.

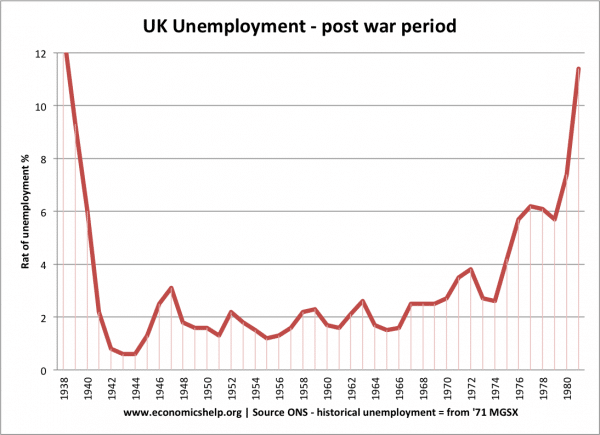

The main reason UK debt to GDP fell in the post-war period was the sustained period of economic growth and near full employment until the late 1970s. This growth saw rising real incomes which in turn led to higher tax revenues and falling debt to GDP ratios.

There was also a positive inflation rate, which helped erode the real value of debt.

Higher government spending in post-war period

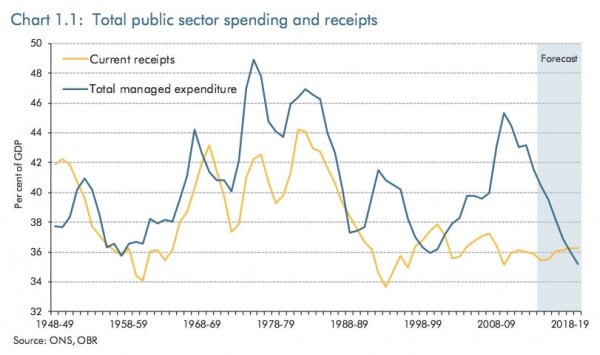

Firstly, debt to GDP was definitely not reduced through cutting government expenditure.

Note – Debt to GDP fell, despite higher real government spending on the newly formed welfare state and national health service. In fact, government spending as a % of GDP rose from around 35% of GDP in the early 1950s to the high 40%s in the 1970s.

Source: OBR, Dec 2014

Why did UK debt to GDP fall?

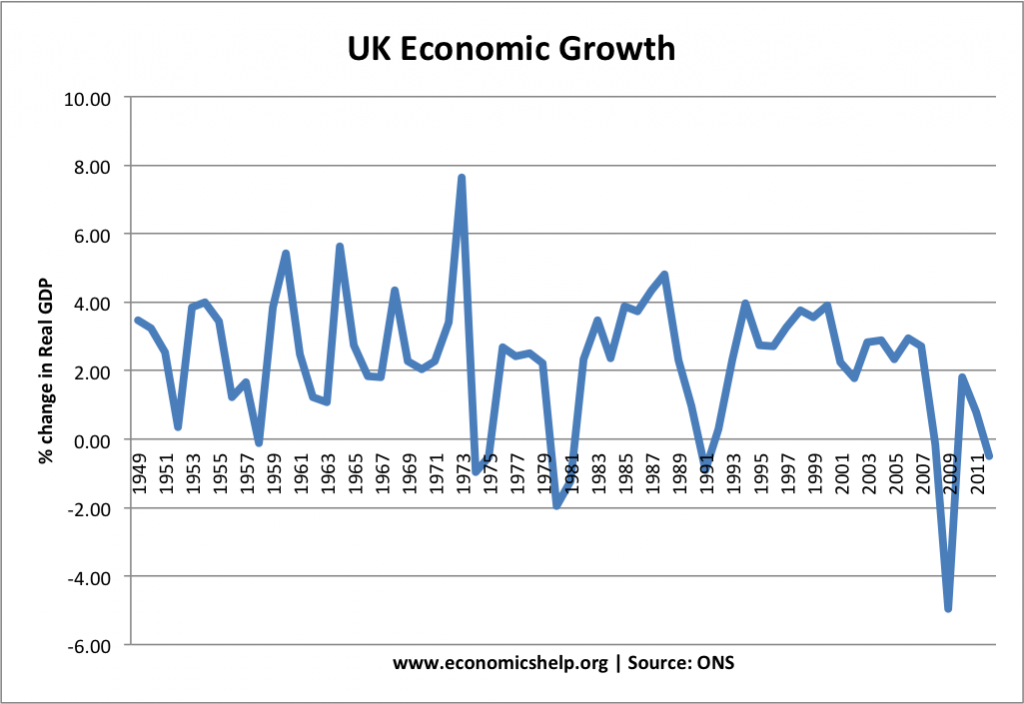

- Economic growth was averaging 2.5% +. Total real debt increased in this period, but GDP increased at a faster rate. Therefore, the debt to GDP ratio fell.

- Positive inflation.

- Patience. After the early 1950s, debt to GDP fell over the next four decades. It took a long time to reduce debt to GDP.

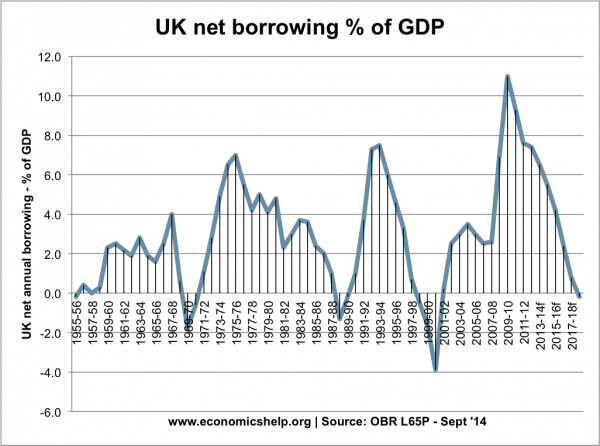

- Relatively low budget deficits (though the UK very rarely had a budget surplus)

Postwar economic boom

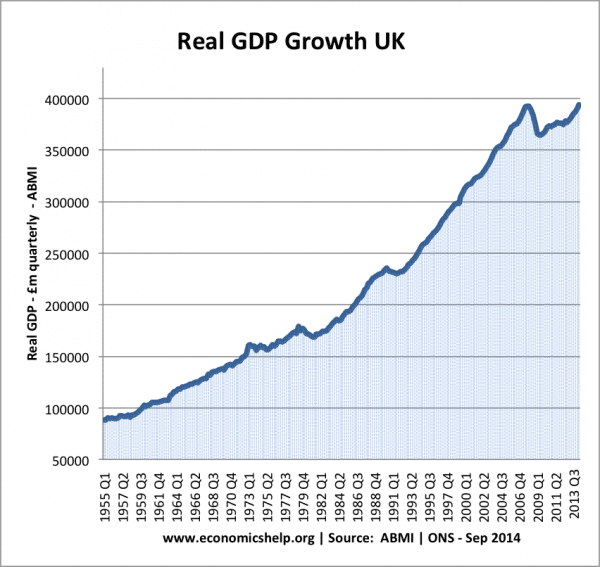

This graph shows UK real GDP. In 1955 it was less than £100,000 m (quarterly). By the early 1970s, real GDP had doubled in a relatively short period of time.

This graph also explains the sharp rise in debt as a % of GDP 2007-2013 – real GDP stagnated and stopped growing.

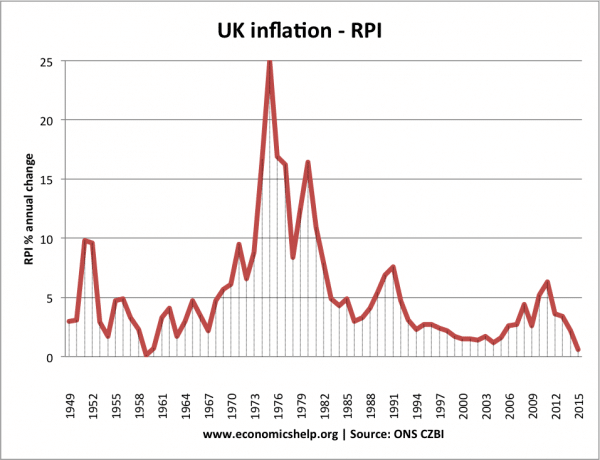

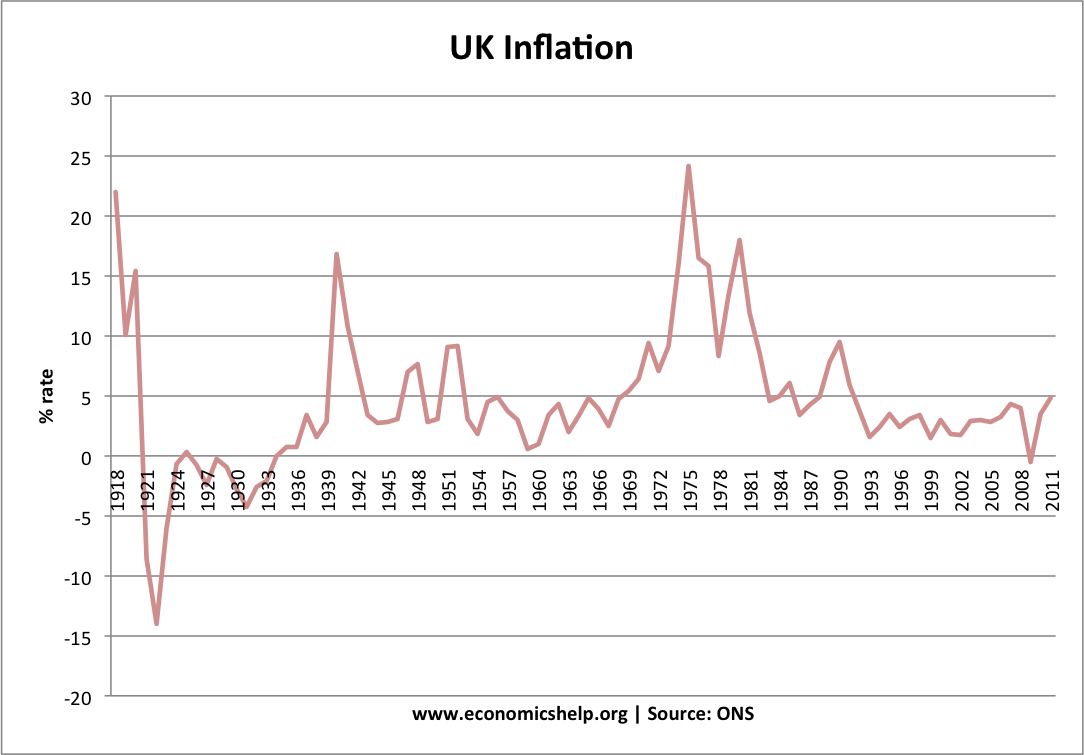

UK post-war inflation

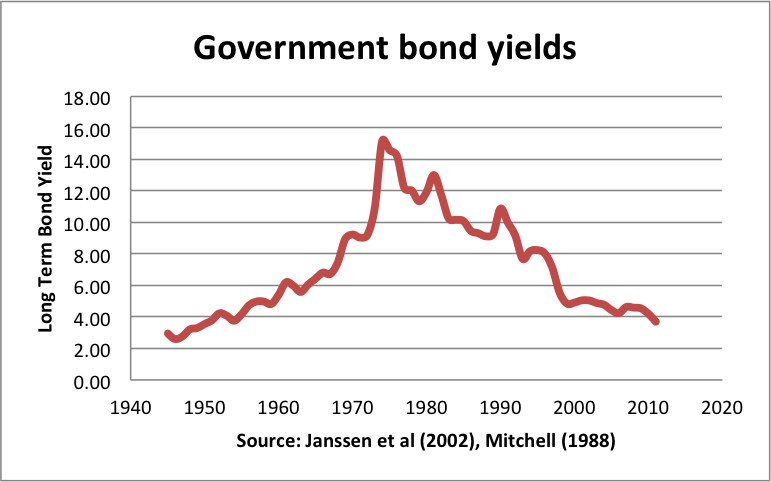

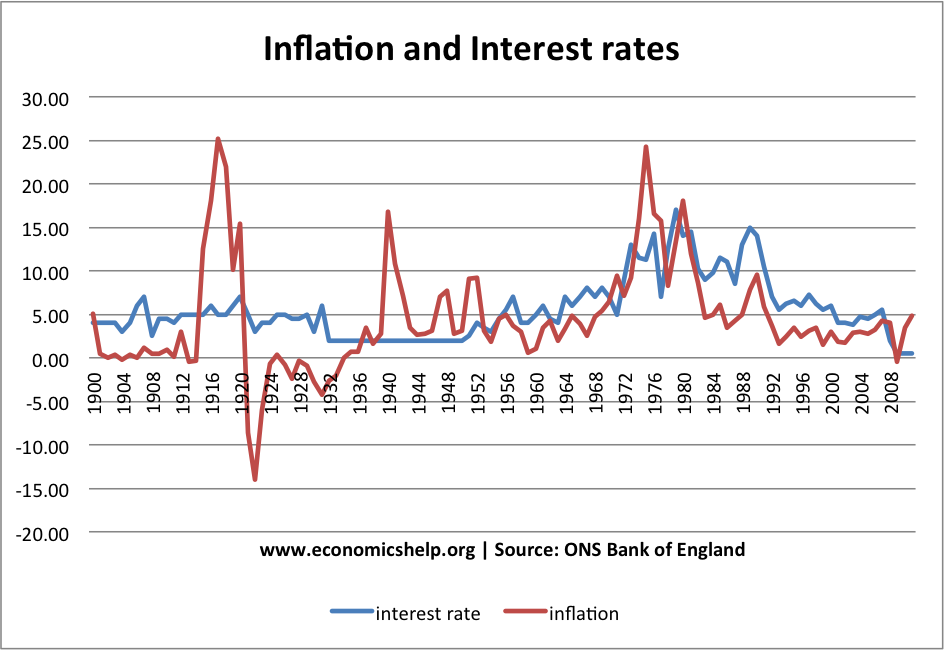

Inflation helps reduce the real value of debt. This occurred in the 1970s. Though interest rates did rise in the 70s to give some compensation to bondholders.

UK post-war budget deficit

Unemployment

What caused economic growth in the post-war period?

- Global economic boom

The UK economy benefited from the period of rapid global economic growth, especially in Western Europe. In fact, in this period, UK growth lagged behind many of our Western European neighbours. But, overall the UK enjoyed a period of rapid growth in trade and economic growth. The global economic boom was helped by

- Recovery of Japan and Germany

- Low global inflation

- Increased free trade, with reduction of tariff barriers

- Relative political and economic stability

- Technological improvements, such as computers, better petrol engines. Some of these technological improvements were quite low-tech like containerisation,

2. Immigration

UK growth was so rapid, the economy experienced labour shortages. This led to the mass immigration of the 1950s and 60s to help deal with the labour market shortages. This helped increase the working population and increase real GDP. GDP per capita rose at a slower pace than actual real GDP.

3. Improved education

In the post-war period, there was a growth in university education, and secondary education became more comprehensive.

4. Effective demand management

One of the cornerstones of William Beveridge’s Welfare proposals was the assumption that a comprehensive welfare state required considerable efforts to achieve near full employment. The UK experienced boom and bust cycles, but the downturns were relatively minor, and there were no real recessions of any significance until 1973.

In the post-war period, the government controlled monetary policy and fiscal policy and had a willingness to cut interest rates during economic slowdowns. The benign global economic conditions helped give a low trade-off between inflation and unemployment.

UK growth could have been higher

Many commentators state that although the UK did enjoy a post-war economic boom, it was actually a missed opportunity and our relative competitiveness declined. The UK had many failings such as

- Uncompetitive industry

- Poor industrial relations

- Lack of vocational training

- A degree of complacency – not felt in countries, such as Japan and Germany.

High tax rates

Another feature of the 1940s, 50s and 60s were very high tax rates. The Second World War created a political climate which tolerated extremely high-income tax rates. The highest rate of income tax peaked in the Second World War at 99.25%. It was slightly reduced after the war and was around 90% through the 1950s and 60s.

In 1971 the top-rate of income tax on earned income was cut to 75%. Though a surcharge of 15% on investment income kept the top rate on that income at 90%. The top rate of income tax was cut to 40% in the late 1980s.

With income tax rates of 70% plus. Rising incomes will lead to significant increase in tax revenues for the government.

There was more effort to tax capital. In 1965, James Callaghan, the then chancellor introduced capital gains tax of 30pc to stop people avoiding income tax by switching their income into capital.

Tax revenue was regularly over 40% of GDP.

Inflation higher than interest rates?

Inflation played a role in helping to erode the real value of debt. In the post-war period inflation was averaging 3-5% – with periods of near double-digit inflation.

The 1940s and early 1950s saw periods where inflation was above Bank of England interest rates; there were also periods in the 1970s when some of the debt was reduced through the effects of inflation – to some extent a period of ‘inflating away the debt. However, in the 1950s, and 1960s, real interest rates were positive. It wasn’t just a matter of inflating away the debt. (see blog on inflating away the debt?)

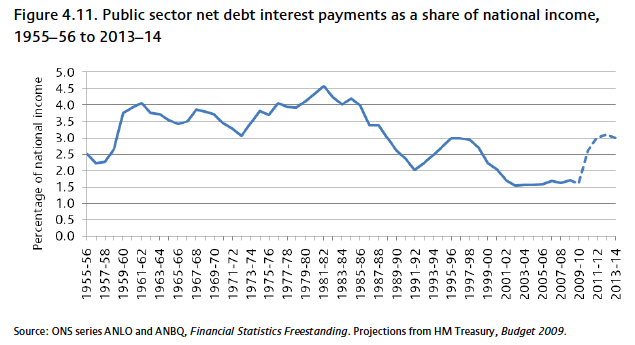

Despite the high levels of UK debt, the cost of servicing UK debt remained relatively low (less than 4% of GDP). This is a reflection of relatively low-interest rates. It is also interesting to note the current cost of servicing national debt is lower than in the 50s, 60s, and 70s.

Conclusion

The fall in UK national debt as a % of GDP reflects one of the important issues regard to debt reduction – take care of economic growth and unemployment and this will play a considerable role in reducing debt to GDP ratios.

The UK experience of the 1950s and 60s is in complete contrast to the current European experiment of sacrificing growth to meet deficit reduction targets – the result being often rising debt to GDP ratios in Europe.

However, it is worth bearing in mind, the post war period is often referred to as the ‘golden period of economic expansion’. The UK was helped by several factors which enabled it to borrow such a large amount. These factors included:

- High personal savings ratio

- Patriotic effect of buying ‘war bonds’

- Generous loan from the US which we took a long time to pay back.

- Rapid global growth which made debt reduction much easier.

In the current climate many of these factors are not there.

Burnt by the credit crunch, investors are possibly more sceptical about government debt (though that hasn’t stopped UK bond yields falling to near record levels)

The outlook for global growth looks less promising – especially with our main trading partners.

It is all very well saying all we need to do is to increase real incomes and boost economic growth, but in practise it might not be as easy as that.

Could the UK happily borrow 230% of GDP like in the late 1940s? – I don’t think so. But, when politicians tell you the only way to reduce debt is through painful austerity, you could remind them of the 1950s and 1960s when the opposite happened. The striking thing is the steady reduction in debt to GDP, whilst at the same time seeing real government spending levels rise.

Debt as % of GDP more important than budget deficit

One final point is that debt as % of GDP is a more important statistic than a budget deficit. Total debt reflects the long-term situation better than annual deficits which are influenced by cyclical factors.

Related

Footnotes

(1) note there are different measures of government debt. But, whichever method you use, there is a broad decline in debt to GDP

You make the point that the debt to GDP fell in the post war period since the GDP rose faster than the debt but that still left the debt to be repaid and as such there was still the interest to be paid. I was expecting you to explain how the current debt could be eliminated. It is so large thatI can’t see how it can be done. Talks of reducing the deficit pale into insignificance in the light of reducing the total debt.

You have partially explained the answer to my question in your reply to my other question, “What will we do when we can’t pay back the money owing to the goverment bond holders when they reach the end if their term”. While I appreciate the convenient use of the debt to GDP ratio I feel that it tends to sidestep the truth about the remaining debt. This is almost like the government using the reduction in the deficit rather than the reality of remaining, possibly increasing debt.

Lee Shipton.

Suppose you have a job working in a supermarket. You work 40 hour weeks and the job pays the minimum wage of £6.50/hr, so you make about £13k p.a. You have been struggling to pay the rent, so you have credit card debt to the tune of £5000.

If you move into a houseboat and work overtime, you know that you might be able to pay off the £5000 within 3 years.

However, you were always top of the class in school – you’ve just fallen into some bad habits, of late. If you take out a student loan and do a degree, you could be earning £20k after 3 years, and £50k after 6 years. If you then do a (1 year) master’s degree (followed by 3 years of exemplary career progression), you could up your salary a further notch to £80k (let’s say you enter the banking industry), within 10 years of taking out your original student loan.

Somewhere along the line, the £5000 of credit card debt starts not to seem all that serious – even though it has now grown to £10,000, plus the student loan of about £90,000.

Also, over those 10 years, inflation has been 100%, so when I said you end up earning £80k, I actually meant £160k.

The interest on your £100k of combined debt is now piddling in comparison to your income. Let’s say the average rate is 10%, so you are paying £10k p.a. in interest. Even if your creditors find a way to force you to cough up the capital, you can always take out another loan to cover it – probably at a more favourable rate too, given your present circumstances.

Knowing the full extent of your potential, and having a sharp eye for inflationary trends, what kind of fool would you have to be to choose to move into the houseboat and take on the overtime – unless someone was drugging you up to the eyeballs and holding a gun to your head?

Suppose the credit card company sent someone to drug you up to the eyeballs and hold a gun to your head. Or, to put it another way, suppose they sent your ministers backhanders and told your electorate a pack of lies…

I think the effect of inflation has been left out of the narrative and it certainly deserves a mention.

According to Reinhart and Rogoff there are several hundred instances of countries reducing the ‘real’ value of their debts by inflating their way out of trouble. And in bad times people seem more ready to accept 3% pay rises when inflation is 4% far more readily than no rise at all when inflation is 1%.

Scrub that post, wrong site.

Thanks for the explanation, to make a subject so simple.

So that said, our National Debt at 80% of GDP by historical trends is low, so to is our deficit at 4%. Though the concern is that we have a structural deficit. Then again so did the chap working in the Supermaket.

This leaves the concern of who would lend the money to the UK if the debt were to increase especially with the UK being at the top of the economical cycle, during the next recession is when the additional monies will be required, i.e, we have a structural deficit.

That leaves another debate, if the economy is going to be reflated, what is the best way to do this.

Increased public spending – infrastructure, benefits, NHS, Defense.

OR

Tax cuts?? leave reflation to the free market.

I like your explanation on tax rates too.

we joined the e u in 1973 it appears things got worse from then please let us get back and out of the E U

Chaz – We Joined the EEC in 1973 not the EU. We Joined the EU in 1993. It is strange that it is forgotten that before the EEC we were in EFTA. EFTA was a Free Trade Area, the EEC a Customs Union and the EU a Single Market with Customs Union. Since joining the EU, the UK GDP Growth took a step up until 2008/9 with the Bank Crisis. It is unequivocally seen in the GDP Graph shown above. EU Membership has benefited the UK more than membership of either EFTA (with the UKs historic access to Old Empire Countries) or the EEC. But let’s not let historic facts get in the way of a good Brexit Argument. I have lived through all of this time and the EU years have been the best. I wonder why we gave up the Empire Markets and EFTA in favour of the EEC and then the EU, answer because they were rubbish, by comparison. No decade since the end of WW2 has been better. I am so glad that by the time we Leave the EU completely, I shall have retired. That is of course if the Tories do not implode before hand and Brexit collapses.

“The UK economy benefited from the period of rapid global economic growth, especially in Western Europe. In fact, in this period, UK growth lagged behind many of our Western European neighbours. But, overall the UK enjoyed a period of rapid growth in trade and economic growth. The global economic boom was helped by”

It was NOTHING to do with global growth. A global growth only occurs to you if you are competing well. In the post war years we dealt with our debts and were a major export nation. That was due to heavy investment in science, technology and British manufacturing. When that stopped, after the 1950’s, things started to go into reverse. And yes, things have got worse since entry into the EU.

Holy cow, im 14 and this stuff sounds pretty complex (im just starting to dive into economy and such..